Pioneer Institute’s 2021 Government Transparency Resolutions: Sunshine Week Edition

In 2020, Pioneer Institute continued its work to support fully accountable and efficient governance in the Commonwealth, in part by publicizing more thoughtful reopening procedures in K-12 education, calling for an extension of the term of the MBTA’s Fiscal & Management Control Board, questioning Governor Baker’s July travel order, keeping tabs on who is benefitting from Paycheck Protection Program loans, and fighting for improved access to COVID-19 information in nursing homes.

Still, only modest transparency reforms have passed on the state level since the Center for Public Integrity gave the Massachusetts government a D+ for accountability in 2015. In 2021, Pioneer’s work to promote more open government is far from over.

As it does each year, Pioneer shares the resolutions it hopes state leaders will adopt to bring government actions into better focus and invigorate our democracy with heightened public engagement. As the late Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis noted, “sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.”

Education

Ensure rigorous standards for a remote learning environment.

K-12 Public schools in Massachusetts were unprepared to shift to remote learning when COVID-19 struck, and as a result many students lost a third of their academic year. Many individual teachers made extraordinary efforts to re-organize lesson plans and shift to online tools, but without a statewide system that was able to respond to the need for more remote learning resources, these efforts were not enough. Schools must maintain robust testing and grading standards going forward and prioritize science-based adaptations to COVID over appeasing overwrought fears. COVID-19 should not be an excuse for stunting the potential of an entire generation of kids. With this in mind, parents, educators, and other stakeholders must continue to seek improvements to state oversight efforts while many students remain in virtual classrooms.

K-12 Public schools in Massachusetts were unprepared to shift to remote learning when COVID-19 struck, and as a result many students lost a third of their academic year. Many individual teachers made extraordinary efforts to re-organize lesson plans and shift to online tools, but without a statewide system that was able to respond to the need for more remote learning resources, these efforts were not enough. Schools must maintain robust testing and grading standards going forward and prioritize science-based adaptations to COVID over appeasing overwrought fears. COVID-19 should not be an excuse for stunting the potential of an entire generation of kids. With this in mind, parents, educators, and other stakeholders must continue to seek improvements to state oversight efforts while many students remain in virtual classrooms.

Keep state officials accountable during the standardized testing debate.

Massachusetts’ MCAS test system ground to a halt after COVID-19 shifted the priorities of K-12 administrators statewide. Teachers’ unions seized on the opportunity to call for a 4-year moratorium on the test, but such a policy would be dangerously misguided. The development of the MCAS test in 1993 has been closely tied to subsequent improvements in academic performance in our public schools. Instead of scrapping it, state officials should expand the availability of online test prep materials and remote proctoring. Even after COVID, this will make the material more accessible to students with special needs and strengthen the resilience of the public education system. The fight over MCAS is a crucial test of the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s commitment to kids’ needs.

Massachusetts’ MCAS test system ground to a halt after COVID-19 shifted the priorities of K-12 administrators statewide. Teachers’ unions seized on the opportunity to call for a 4-year moratorium on the test, but such a policy would be dangerously misguided. The development of the MCAS test in 1993 has been closely tied to subsequent improvements in academic performance in our public schools. Instead of scrapping it, state officials should expand the availability of online test prep materials and remote proctoring. Even after COVID, this will make the material more accessible to students with special needs and strengthen the resilience of the public education system. The fight over MCAS is a crucial test of the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s commitment to kids’ needs.

Improve transparency of higher education reserve accounts.

Massachusetts’ public higher education institutions should disclose the balances of each campus’s primary reserve account. These accounts are used to pay for campus-funded capital building projects and protect against operating budget shortfalls on a semi-annual basis. Errors in management and the lack of transparency of these off-budget accounts led to the UMass-Boston financial crisis in 2019. Transparency is one sure way to protect against such a calamity.

Massachusetts’ public higher education institutions should disclose the balances of each campus’s primary reserve account. These accounts are used to pay for campus-funded capital building projects and protect against operating budget shortfalls on a semi-annual basis. Errors in management and the lack of transparency of these off-budget accounts led to the UMass-Boston financial crisis in 2019. Transparency is one sure way to protect against such a calamity.

Healthcare

Improve the oversight, transparency and administration of long-term care facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed just how many nursing homes and assisted living facilities lack sufficient infection control and prevention protocols. As of February 2021, nursing homes account for a majority of COVID deaths in Massachusetts. Oversight of these facilities is fragmented among several state and federal agencies, including DPH, MassHealth, federal HHS, and the state Office of Elder Affairs. This fragmented regulatory oversight has had dire consequences for nursing homes during the pandemic. Preventing a repeat of such outcomes requires significant reforms: a single long-term care facility office that reports directly to the Governor, headed by public health experts, with the authority and budget to appropriately oversee the safety of residents in such entities; the adoption of proven infection control and prevention measures including protocols for rapid testing, access to sufficient PPE for all staff, separating infected residents and having the physical space to do so, and the segregating of staff caring for infected residents from those who are not infected; and the availability of consumer-friendly data regarding cumulative and recent infectious disease cases and deaths by facility and in total across the state.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed just how many nursing homes and assisted living facilities lack sufficient infection control and prevention protocols. As of February 2021, nursing homes account for a majority of COVID deaths in Massachusetts. Oversight of these facilities is fragmented among several state and federal agencies, including DPH, MassHealth, federal HHS, and the state Office of Elder Affairs. This fragmented regulatory oversight has had dire consequences for nursing homes during the pandemic. Preventing a repeat of such outcomes requires significant reforms: a single long-term care facility office that reports directly to the Governor, headed by public health experts, with the authority and budget to appropriately oversee the safety of residents in such entities; the adoption of proven infection control and prevention measures including protocols for rapid testing, access to sufficient PPE for all staff, separating infected residents and having the physical space to do so, and the segregating of staff caring for infected residents from those who are not infected; and the availability of consumer-friendly data regarding cumulative and recent infectious disease cases and deaths by facility and in total across the state.

Strengthen state healthcare price transparency laws.

There are many reasons why healthcare price increases continue to outpace wage growth, but one of the biggest is that consumers often find it difficult to compare the prices of healthcare services across institutions. In fact, most states don’t require providers or insurance companies to make pricing information available to consumers before they purchase a service. Even in states that do, most consumers are either unaware that they’re entitled to this information or otherwise don’t know where to obtain it. The result is that, in Suffolk County, Massachusetts alone, consumers could have saved an estimated $116.6 million over four years for about 15 shoppable healthcare services by switching from the highest priced providers to those whose prices are closer to the average. With the national debate over soaring healthcare prices continuing to rage during COVID-19, efforts to make pricing information more available ahead of purchase could provide some relief to consumers. These efforts include making sites like MassCompareCare.gov more accessible and user-friendly and using research to identify how well Massachusetts providers are complying with both state and federal transparency laws.

There are many reasons why healthcare price increases continue to outpace wage growth, but one of the biggest is that consumers often find it difficult to compare the prices of healthcare services across institutions. In fact, most states don’t require providers or insurance companies to make pricing information available to consumers before they purchase a service. Even in states that do, most consumers are either unaware that they’re entitled to this information or otherwise don’t know where to obtain it. The result is that, in Suffolk County, Massachusetts alone, consumers could have saved an estimated $116.6 million over four years for about 15 shoppable healthcare services by switching from the highest priced providers to those whose prices are closer to the average. With the national debate over soaring healthcare prices continuing to rage during COVID-19, efforts to make pricing information more available ahead of purchase could provide some relief to consumers. These efforts include making sites like MassCompareCare.gov more accessible and user-friendly and using research to identify how well Massachusetts providers are complying with both state and federal transparency laws.

Improve the transparency of the state’s vaccination efforts.

Massachusetts’ current COVID-19 vaccination dashboard could be enhanced significantly by showing the percent of people in various demographic groups who have received the shot. Currently, the state only shows the percent of each age, ethnic, and racial group vaccinated out of total doses. Although that is important data for the public, it is also very important to be able to compare the share of the population that is vaccinated across age, race, and ethnic categories. The state certainly has this data, as it only requires expressing the current vaccine counts as broken up by race on a per-capita basis. Publishing this data would allow for more informed examination of the effectiveness of the state’s vaccine rollout, especially regarding theassociated equity concerns.

Massachusetts’ current COVID-19 vaccination dashboard could be enhanced significantly by showing the percent of people in various demographic groups who have received the shot. Currently, the state only shows the percent of each age, ethnic, and racial group vaccinated out of total doses. Although that is important data for the public, it is also very important to be able to compare the share of the population that is vaccinated across age, race, and ethnic categories. The state certainly has this data, as it only requires expressing the current vaccine counts as broken up by race on a per-capita basis. Publishing this data would allow for more informed examination of the effectiveness of the state’s vaccine rollout, especially regarding theassociated equity concerns.

Publish the administrative costs associated with COVID-19 vaccination sites.

Although the actual doses of COVID vaccines are free (purchased by the federal government), those providing doses are allowed to charge administration fees. The Commonwealth should disclose essential terms of its contracts with private companies that are running the state’s mass vaccination sites and make public the terms of any subcontracts with such private companies. The Commonwealth should also disclose the amounts of payments to all providers or other companies made by state health insurers and MassHealth for administering vaccine doses.

Although the actual doses of COVID vaccines are free (purchased by the federal government), those providing doses are allowed to charge administration fees. The Commonwealth should disclose essential terms of its contracts with private companies that are running the state’s mass vaccination sites and make public the terms of any subcontracts with such private companies. The Commonwealth should also disclose the amounts of payments to all providers or other companies made by state health insurers and MassHealth for administering vaccine doses.

Transportation

Disclose financing information for the I-90 Allston Multimodal project.

MassDOT’s initiative to replace a structurally deficient viaduct over a rail line with a new urban highway interchange and almost four million square feet of development in Allston is bound to come with a 10-figure price tag. Public comments by Pioneer recommended that the finance plan should be prepared in a transparent manner with significant public input. Furthermore, recent meeting materials for the project make little effort to compare construction or long-term costs across the several proposed design plans. Additional transparency on this project is of the utmost importance, as disruptions on the Mass Pike and Framingham/Worcester Commuter Rail line will likely drag into the 2030s.

MassDOT’s initiative to replace a structurally deficient viaduct over a rail line with a new urban highway interchange and almost four million square feet of development in Allston is bound to come with a 10-figure price tag. Public comments by Pioneer recommended that the finance plan should be prepared in a transparent manner with significant public input. Furthermore, recent meeting materials for the project make little effort to compare construction or long-term costs across the several proposed design plans. Additional transparency on this project is of the utmost importance, as disruptions on the Mass Pike and Framingham/Worcester Commuter Rail line will likely drag into the 2030s.

Make concerted efforts to understand how people will use the MBTA after COVID-19 and publicly disclose the results.

During the pandemic, ridership on Boston’s subway network declined by 85 percent. It will likely be years before ridership returns to pre-pandemic levels, and given an increased appetite for remote work, commuting patterns could change in unanticipated ways. Thus, the MBTA should ramp up efforts to survey riders – both past and present – on how, when, and whether they plan to use public transit in the future. This includes not only paper surveys handed out on trains and buses but also electronic ones delivered through mTicket and similar apps. This information will help guide service provision and long-term planning decisions going forward, leaving the agency better prepared to keep riders happy and its balance sheet in order. All survey information should be publicly disclosed to improve private sector decision-making as well.

During the pandemic, ridership on Boston’s subway network declined by 85 percent. It will likely be years before ridership returns to pre-pandemic levels, and given an increased appetite for remote work, commuting patterns could change in unanticipated ways. Thus, the MBTA should ramp up efforts to survey riders – both past and present – on how, when, and whether they plan to use public transit in the future. This includes not only paper surveys handed out on trains and buses but also electronic ones delivered through mTicket and similar apps. This information will help guide service provision and long-term planning decisions going forward, leaving the agency better prepared to keep riders happy and its balance sheet in order. All survey information should be publicly disclosed to improve private sector decision-making as well.

Maintain oversight of the MBTA’s finances.

At the same time as the pandemic allowed the T to ramp up capital spending, a heavy reliance on ridership for revenue left it saddled with a potential $500 million deficit for Fiscal Year 2021. At one point, the T was considering some drastic service cuts to avoid going further into debt, but the Biden administration’s vows to bail out transit agencies nationwide may render these cuts unnecessary for now. Instead, the MBTA should focus on reforms that will make its maintenance obligations and operating procedures more sustainable in the long-term. Pioneer has floated the idea of privatizing some bus services that have low enough ridership to carry passengers via vehicles that are smaller than 40-foot MBTA buses.

At the same time as the pandemic allowed the T to ramp up capital spending, a heavy reliance on ridership for revenue left it saddled with a potential $500 million deficit for Fiscal Year 2021. At one point, the T was considering some drastic service cuts to avoid going further into debt, but the Biden administration’s vows to bail out transit agencies nationwide may render these cuts unnecessary for now. Instead, the MBTA should focus on reforms that will make its maintenance obligations and operating procedures more sustainable in the long-term. Pioneer has floated the idea of privatizing some bus services that have low enough ridership to carry passengers via vehicles that are smaller than 40-foot MBTA buses.

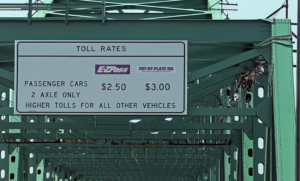

Create a Pay-by-Plate collections transparency tool.

Toll payers should know if their tolls are subsidizing other drivers who use the Massachusetts Turnpike, the Tobin Bridge, and harbor tunnels who don’t have a transponder and are not paying their bills under the Pay-by-Plate (PBP) system. MassDOT should create a real-time tool that shows toll billing captured through transponders, tolls to be billed through PBP, and tolls not billed because of PBP errors. The tool should also show PBP toll collections, the amount not yet collected, and the amount of write-offs by state of vehicle registration.

Toll payers should know if their tolls are subsidizing other drivers who use the Massachusetts Turnpike, the Tobin Bridge, and harbor tunnels who don’t have a transponder and are not paying their bills under the Pay-by-Plate (PBP) system. MassDOT should create a real-time tool that shows toll billing captured through transponders, tolls to be billed through PBP, and tolls not billed because of PBP errors. The tool should also show PBP toll collections, the amount not yet collected, and the amount of write-offs by state of vehicle registration.

Anti-corruption and General Accountability

Improve public access to financial statements of government officials.

Over a year after Pioneer released its state rankings on transparency over lawmakers’ conflicts of interest, reforms that would encourage accountability for public officials remain elusive. It is exceedingly difficult for the public to access Statements of Financial Interest (SFIs) submitted by these officials, and in the era of social distancing they are not even required to submit them online in Massachusetts. U.S. senators’ insider trading in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is only one of many examples of similar conflicts of interest that have arisen in the past year, and the public deserves to know whether such abuses of power are also occurring at the state level.

Over a year after Pioneer released its state rankings on transparency over lawmakers’ conflicts of interest, reforms that would encourage accountability for public officials remain elusive. It is exceedingly difficult for the public to access Statements of Financial Interest (SFIs) submitted by these officials, and in the era of social distancing they are not even required to submit them online in Massachusetts. U.S. senators’ insider trading in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is only one of many examples of similar conflicts of interest that have arisen in the past year, and the public deserves to know whether such abuses of power are also occurring at the state level.

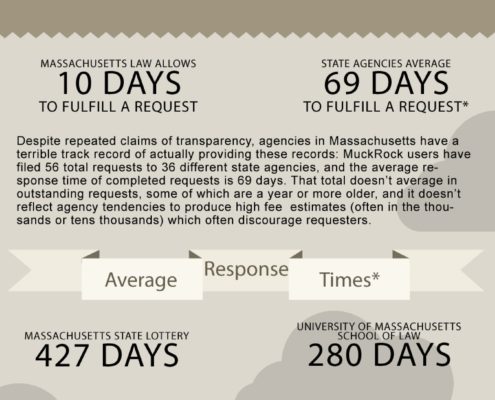

Include the state Legislature under the definition of “public body.”

Under Massachusetts law, the state Legislature is not considered a “public body” in the traditional sense, and therefore enjoys exemptions from open meeting and public records laws. Pioneer Institute believes this is unconstitutional. The state constitution says the legislature should be accountable to citizens “at all times.” In a 2015 report from the Center for Public Integrity, Massachusetts earned an F for public access to information, with one of the reasons cited as the legislature’s and governor’s exemptions from public records laws. The laws that apply to municipalities and the rest of state government should also apply to the legislature. Period.

Under Massachusetts law, the state Legislature is not considered a “public body” in the traditional sense, and therefore enjoys exemptions from open meeting and public records laws. Pioneer Institute believes this is unconstitutional. The state constitution says the legislature should be accountable to citizens “at all times.” In a 2015 report from the Center for Public Integrity, Massachusetts earned an F for public access to information, with one of the reasons cited as the legislature’s and governor’s exemptions from public records laws. The laws that apply to municipalities and the rest of state government should also apply to the legislature. Period.

Eliminate the Governor’s Office “executive order” privilege.

A curtain of darkness fell on the State House when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court published its opinion on Lambert v. Executive Director of the Judicial Nominating Council. For nearly a quarter century, this 1997 ruling has shielded each of our state’s governors, empowering their respective offices to fulfill public records requests “at the office’s discretion.” In 2016, Pioneer sent a letter to Governor Baker asking him to take bold action on this front. We have yet to hear his response.

A curtain of darkness fell on the State House when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court published its opinion on Lambert v. Executive Director of the Judicial Nominating Council. For nearly a quarter century, this 1997 ruling has shielded each of our state’s governors, empowering their respective offices to fulfill public records requests “at the office’s discretion.” In 2016, Pioneer sent a letter to Governor Baker asking him to take bold action on this front. We have yet to hear his response.

Ensure that future public health actions do not curb open government practices.

Coupled with the COVID-19 shutdowns’ economic impacts were a number of overreaching executive orders that damaged the public’s trust in government at a time when trusting government was crucial. The conversation on how best to respond to the virus while preserving fundamental personal freedoms is ongoing, but to facilitate this conversation Pioneer has released online platforms for reporting violations of both civil liberties and open meeting law violations related to the pandemic.

Coupled with the COVID-19 shutdowns’ economic impacts were a number of overreaching executive orders that damaged the public’s trust in government at a time when trusting government was crucial. The conversation on how best to respond to the virus while preserving fundamental personal freedoms is ongoing, but to facilitate this conversation Pioneer has released online platforms for reporting violations of both civil liberties and open meeting law violations related to the pandemic.

Other

Ensure robust COVID-19 data reporting.

In the midst of a scandal last spring that revealed undeserving companies receiving Paycheck Protection Program loans, the Small Business Administration released a list of every company that received at least $150,000 in public funds from the program. This was a good start, but it also shouldn’t take a national scandal for the government to make this data publicly available. In fact, many aspects of the pandemic response could benefit from additional data reporting, from school reopening efforts to the economic fallout to all manners of federal funding. This data will help inform local decision makers, and COVID-19 case counts weren’t even available at the local level.

In the midst of a scandal last spring that revealed undeserving companies receiving Paycheck Protection Program loans, the Small Business Administration released a list of every company that received at least $150,000 in public funds from the program. This was a good start, but it also shouldn’t take a national scandal for the government to make this data publicly available. In fact, many aspects of the pandemic response could benefit from additional data reporting, from school reopening efforts to the economic fallout to all manners of federal funding. This data will help inform local decision makers, and COVID-19 case counts weren’t even available at the local level.

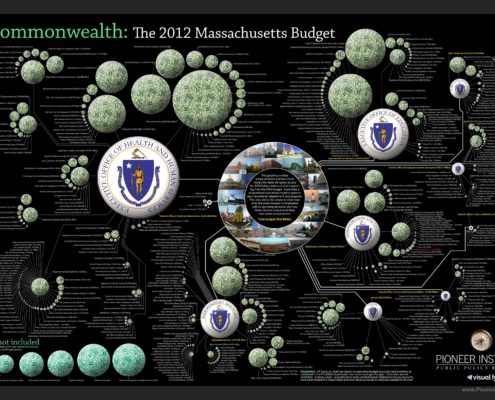

Create the state equivalent of the Congressional Budget Office.

Currently, the Massachusetts Department of Revenue’s capacity to make precise revenue estimates for specific proposals is severely limited. One state senator even opined that the uncertainty of COVID-induced budget shortfall estimates from the agency “made it hard for budget writers to pin down an exact revenue estimate.” An independent office would be better equipped to conduct cost-benefit analyses for bills that would raise revenue or spending. A Massachusetts office run by the Inspector General to independently assess bills with an expected budgetary impact over $1 million would improve decision making, accountability, efficiency, and public trust. This office would be required to publish each analysis on its website in a timely manner and include the assumptions behind it. To ensure independence, the Inspector General should be limited to a single six-year term.

Currently, the Massachusetts Department of Revenue’s capacity to make precise revenue estimates for specific proposals is severely limited. One state senator even opined that the uncertainty of COVID-induced budget shortfall estimates from the agency “made it hard for budget writers to pin down an exact revenue estimate.” An independent office would be better equipped to conduct cost-benefit analyses for bills that would raise revenue or spending. A Massachusetts office run by the Inspector General to independently assess bills with an expected budgetary impact over $1 million would improve decision making, accountability, efficiency, and public trust. This office would be required to publish each analysis on its website in a timely manner and include the assumptions behind it. To ensure independence, the Inspector General should be limited to a single six-year term.

Get our MassWatch updates!

Related content