This Is No Time for a Tax Increase

This is no time to threaten Massachusetts’ prospects for an immediate economic recovery and the long-term competitiveness of the Commonwealth’s businesses. As Massachusetts lawmakers prepare to vote on whether to send a proposed constitutional amendment that would impose a 4 percent surtax on residents who earn $1 million or more in a year to the statewide ballot in 2022, Pioneer Institute urges them to recognize that tax policy sizably impacts business and job location decisions and that jobs are more mobile than ever.

We call on elected officials to prioritize the 300,000 state residents who were working in February 2020, but are now unemployed after the pandemic ravaged Massachusetts’ private sector workforce. The amendment may benefit the 3 percent of the workforce that is employed by the Commonwealth, but it will do so at the expense of the 90 percent of the overall employment base that works in the private sector. If the legislature approves the measure, their vote cannot be undone.

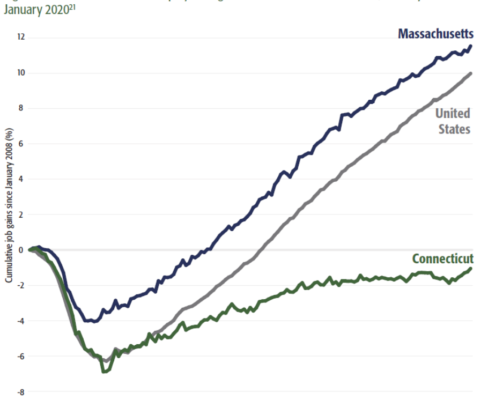

Lessons from Connecticut and California: Our neighbor to the south provides strong evidence of the likely result of adopting the amendment: Connecticut is still recovering from more than a decade of “soak the rich” policies. Between 2008 and 2020, it ranked 49th among the states in private-sector job growth. Many larger companies left the state. So did many wealthy individuals: The taxes paid by the 100 top taxpayers actually fell by 45 percent just between 2015 and 2016. The impact on the state budget is clear: Between 2008 and 2020, Connecticut’s budget grew by 22 percent; Massachusetts chose the path of economic growth and over the same period generated budget growth of 63 percent.

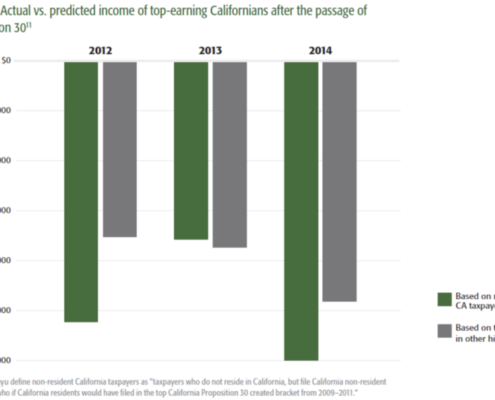

The exodus of companies and jobs out of California after its own graduated tax initiative eroded 61 percent of projected new revenues by just the second year after the tax hike.

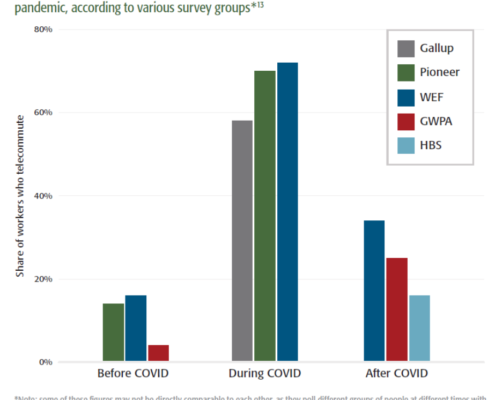

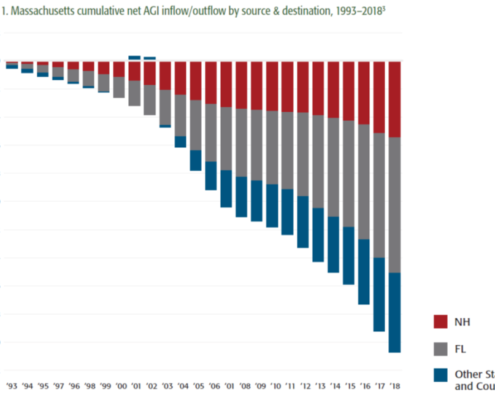

Businesses and individuals have never been more mobile: The world of work shifted dramatically during the pandemic. The proposed constitutional amendment comes just as the rise in telecommuting makes it easier for wealthy taxpayers to live – and pay taxes – anywhere. Massachusetts already loses nearly $1 billion of wealth per year due to residents relocating elsewhere, primarily to low- or no-tax states.

The same is true for businesses. A 2020 Princeton study found that state and local governments lure companies with tax incentives worth at least $30 billion annually. And the companies appear to be responding. The migration rate for large firms in the U.S. nearly doubled in less than 20 years between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, well before the pandemic made telecommuting and the mobility it created the norm.

There’s no assurance that education and transportation funding would increase: Proponents of the amendment teed up what could be the biggest shell game in the state’s history. The amendment does not guarantee that any revenues generated from the new tax would increase overall spending on education and transportation, as supporters claim. Lawyers on both sides of a 2018 Supreme Judicial Court case and the SJC’s chief justice at the time all agreed that it would not violate the amendment if any new revenue for education and transportation generated by the surtax was counterbalanced by diverting funds previously dedicated to those issues.

That’s exactly what happened in California. After a 2012 tax hike “to fund education,” funding increased only to the degree required by existing state funding quotas. Massachusetts has no such quotas, meaning that 100 percent of the new money could be used to replace funds diverted to other priorities.

The fact that the Massachusetts legislature has twice rejected amendment proposals to direct new revenues to education and transportation speaks for itself.

Massachusetts tax policy is more progressive than in most other states: The public employee unions that originally proposed the tax claim that the Commonwealth’s tax system is regressive, citing the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). But ITEP finds that Massachusetts taxes are materially more progressive than the average of the 49 other states and Washington, D.C. ITEP also uses a flawed methodology with outdated information that excludes progressive elements of state taxation.

The amendment’s proponents claim the wealthy are not paying their fair share. The fact is that issues around income and tax equality are best addressed at the federal level. It is relatively easy for people and businesses to move – or move assets – between states, but far less so to leave the country.

Economic growth is already generating billions in surplus: Massachusetts revenues are already about $3.9 billion ahead of budget projections and almost $6 billion ahead of last year’s revenue pace. And billions of one-time federal stimulus funds (estimated to be at least $4.5 billion) will soon arrive.

The Commonwealth’s top priority should be to get the 300,000 residents who no longer have jobs post-pandemic back to work. The second priority should be to ensure that the 90 percent of Massachusetts employees who work in the private sector will benefit from a strong economy a generation from now. This amendment will make Massachusetts less competitive, leading business leaders and entrepreneurs to move investments and jobs elsewhere, or dissuading them from coming here in the first place.

If data and analysis no longer hold sway with the legislature, we trust that voters will, as they have so many times in the past, recognize the adverse impact the tax amendment will have on their livelihoods and those of future generations.

Get Updates on Our Economic Opportunity Research

Related Posts