New Study Shows Significant Wealth Migration from Massachusetts to Florida, New Hampshire

Read media coverage of this report:

Boston Herald:

Taxes driving wealth out of Massachusetts and into Florida, New Hampshire: report

Editorial: Wealthy have options to avoid tax hikes

The Boston Globe: Massachusetts is losing wealthy residents to states with no incomes taxes, such as New Hampshire and Florida

The Bond Buyer: Massachusetts sees wealth exodus

State House News Service: Remote Work Growth Adds Dimension to Tax Debate

Bloomberg Bay State Business: Researcher Andrew Mikula from the Pioneer Institute on their new study that shows wealthy individuals leaving Massachusetts (2:13)

The Howie Carr Show (Greg Sullivan)

Gloucester Daily Times Editorial

Patch: Is Your Empty Building Still Burning The Midnight Oil?

BOSTON – Over the last 25 years, Massachusetts has consistently lost taxable income, especially to Florida and New Hampshire, via out-migration of the wealthy, according to a new Pioneer Institute study.

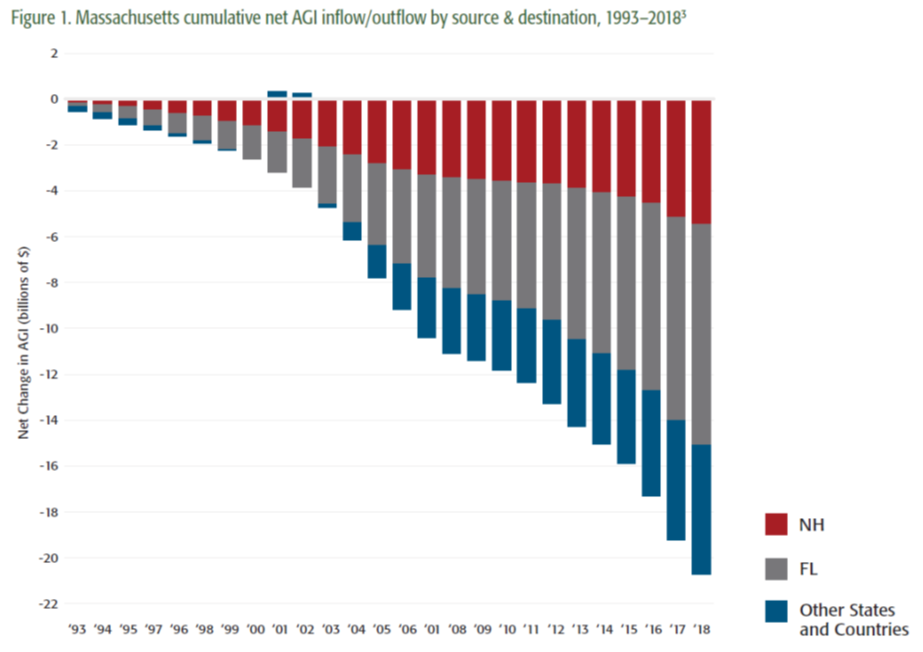

In “Do The Wealthy Migrate Away From High-Tax States? A Comparison of Adjusted Gross Income Changes in Massachusetts and Florida,” Pioneer Institute Research Director Greg Sullivan and Research Assistant Andrew Mikula draw on IRS data showing aggregate migration flows by amount of adjusted gross income (AGI). The data show a persistent trend of wealth leaving high-tax states for low-tax ones, especially in the Sun Belt.

“Because of our stable tax environment and concentration of talent, Massachusetts has outperformed most states and outpaced the nation in job growth since the Great Recession,” said Pioneer Institute Executive Director Jim Stergios. “Yet even during that period of growth we were shedding almost a billion dollars a year to low-tax states like Florida and New Hampshire.”

The report finds that Massachusetts has experienced a net outflow of $20.7 billion in AGI between 1993 and 2018. Unsurprisingly, the biggest beneficiaries were no-income-tax states like Florida, which captured 46 percent of it, and New Hampshire, which gained 26 percent.

“We saw this trend slow down temporarily during the Great Recession, when people became less mobile,” said Sullivan. “But it’s since come roaring back, and the magnitude is staggering.”

Between 2012 and 2018, Florida, which has no income tax or capital gains tax, saw a net $89 billion AGI inflow. Fully 70 percent of that eye-opening number was attributable to taxpayers with AGI of $200,000 or more. Over 30 percent of the total growth in AGI among all Florida taxpayers from 1993 to 2018 was attributable to the state’s net increase in migration. Meanwhile, the only reason why Massachusetts’ total AGI is still growing is because of income gains among stationary residents.

Over the last couple of decades, high rates of immigration have bolstered Massachusetts’ economic health and kept its population stable. However, large rates of domestic out-migration remain a threat to the long-term economic vitality of Massachusetts and much of the rest of the Northeast.

In fact, many of the states that have lost taxable income to Massachusetts on net since 1993 are also in the Northeast, with New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey contributing the most AGI. Some Midwestern states, like Illinois, Ohio, and Michigan, lost smaller amounts. However, considering the substantial wealth migration from Massachusetts to New Hampshire and Maine, geography alone can’t explain broad trends in the flow of capital.

“The legislature needs to be very careful in the new post-pandemic environment, when talent is more mobile,” said Stergios. “Businesses look at the business climate closely – especially tax issues – when they think about location. I’d hate to see us follow in Connecticut’s footsteps toward economic decline.”

Earlier in January, the Institute released “Connecticut’s Dangerous Game,” which demonstrated how multiple rounds of tax increases aimed at high earners and corporations triggered an exodus from Connecticut of large employers and wealthy individuals.

About the Authors

Andrew Mikula is a Research Assistant at Pioneer Institute. Mr. Mikula was previously a Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at Pioneer Institute and studied economics at Bates College.

Gregory Sullivan is Pioneer’s Research Director. Prior to joining Pioneer, Sullivan served two five-year terms as Inspector General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and was a 17-year member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Greg is a Certified Fraud Investigator, and holds degrees from Harvard College, The Kennedy School of Public Administration, and the Sloan School at MIT.

Pioneer’s mission is to develop and communicate dynamic ideas that advance prosperity and a vibrant civic life in Massachusetts and beyond.

Pioneer’s vision of success is a state and nation where our people can prosper and our society thrive because we enjoy world-class options in education, healthcare, transportation, and economic opportunity, and where our government is limited, accountable and transparent.

Pioneer values an America where our citizenry is well-educated and willing to test our beliefs based on facts and the free exchange of ideas, and committed to liberty, personal responsibility, and free enterprise.

Get Updates on Our Economic Opportunity Research

Related Content