Looming Budget Crisis Reveals MBTA’s Dependency on Federal Funds

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, federal lawmakers poured money into transit systems across the country to make up for lost ridership. That temporary assistance is about to expire and the MBTA is not ready for the consequences.

Impending Financial Ruin

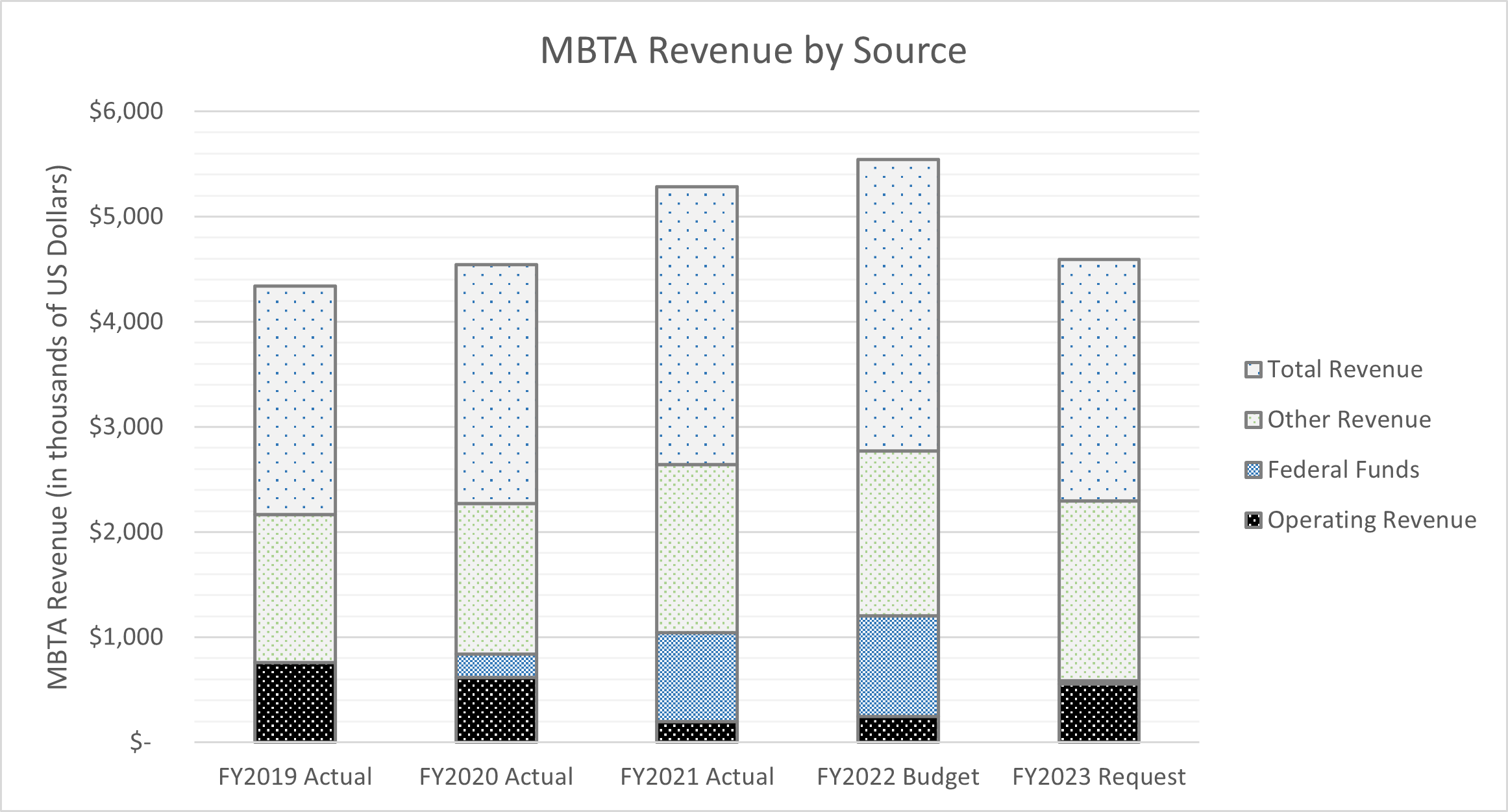

The MBTA’s current budgetary surplus is not going to last. According to the MBTA’s FY2023 budget request that was released last week, the federal money propping up the struggling transit agency is about to dry up. That federal money currently accounts for 34.6 percent of the MBTA’s total revenue (see figure 1). It is about to drop to less than 2 percent in FY2023 (which started on July 1st). The loss of revenue could mean disaster for the MBTA if state government does not step in and help close the funding gap.

Figure 1: MBTA revenue by source for FY2019 – FY2023. The chart shows that federal funds made up a large portion of the MBTA revenue and will no longer be available in FY2023 (which starts July 1st 2022). This chart was created by the author using MBTA itemized budgets available at MBTA.com.

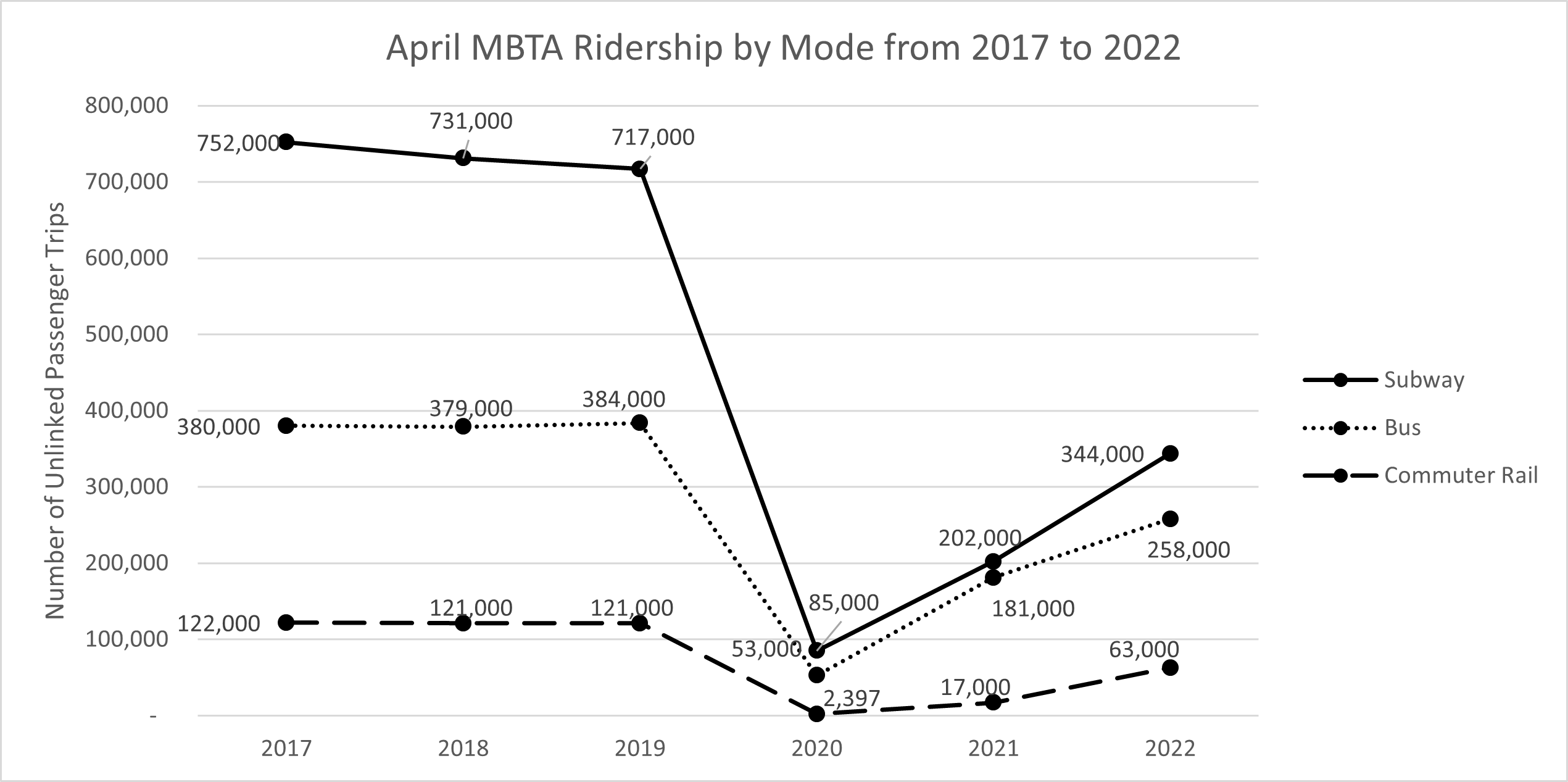

A major loss of fare revenue has caused the MBTA to become over-reliant on federal funds. Ridership has not returned to pre-pandemic levels (see figure 2). In 2020, ridership ground to a near-complete halt. In 2021 and 2022, it has improved significantly, but has only recovered to about half the level it was before the pandemic.

The failure of ridership to fully recover is concerning because many other facets of the economy have returned to normal. And it isn’t clear whether ridership will recover at all. In the meantime, the system desperately needs a stop-gap solution before their federal funds run out.

Figure 2: MBTA ridership by mode during the month of April for 2017-2022. The graph shows ridership for bus, subway, and commuter rail modes respectively. The chart was created by the author using data available from the Pioneer Institute’s MBTA Analysis website. The information is also accessible through the Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s MBTA Dashboard.

While no transit mode has fully recovered its pre-pandemic ridership numbers, buses have experienced a noticeably faster recovery than the other modes (see figure 2). Ridership numbers on the subway and commuter rail are at 48 and 52 percent of their April 2019 level. Bus trips have reached 67 percent of their pre-pandemic level. Bus trips now account for 39 percent of all trips on the MBTA, compared to 31 percent three years ago.

State Intervention

The most obvious solution to a loss of funding is to cut services. With the MBTA, however, cutting services is one of the least viable options. It would likely start a downward spiral of making the MBTA even less useful for whatever riders still choose to utilize the system. Additionally, cutting services would be a failure of the government to serve the people’s needs, especially low-income individuals who rely on public transit to get around.

Instead of cutting services, a large majority of Massachusetts residents say the state should make up the cost. A 2020 poll of Massachusetts residents showed that 66 percent support increasing state funding for transportation to prevent service reductions. It may be that, even if riders are using the T for fewer trips, they still want it to be convenient and accessible when they do need it. Additionally, as a public good, mass transit helps reduce carbon emissions and improve traffic flow by keeping many single-passenger vehicles off the road.

Three Options

When it comes to making MBTA finances viable, the state has at least three options: takeover the MBTA’s debt load, increase the sales taxes for transportation, and contribute funds from this year’s surplus.

The MBTA’s debt is a major burden on its finances. Debt service in FY2022 accounted for about 20 percent of the MBTA budget. The state could take over the MBTA’s debt and incorporate it into the much larger pool of Massachusetts government debt.

The state could also increase sales taxes, including the gas tax, that directly subsidize transportation. This measure would certainly increase revenue for the transit system, but might place too much burden on consumers at a time of high inflation and sky-high gas prices.

Instead, the best option for the Commonwealth is to direct this year’s wellspring of income taxes towards the MBTA. This action would be responsive to the will of the voters and would direct funds towards a service that overwhelmingly benefits low- and middle-income Massachusetts residents.

About the Author: Joseph Staruski is a government transparency intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is currently a Master of Public Policy Student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He was previously an opinions columnist with the Boston College student newspaper, The Heights, and an Intern with the Philadelphia Public School Notebook. He has a BA in Philosophy and the Growth and Structure of Cities from Haverford College. Feel free to reach out via email, LinkedIn, or write a letter to Pioneer’s Office in Boston.