Outsourcing bus services is—by now—conventional wisdom

Outsourcing bus services is—by now—conventional wisdom

As the Finance and Management Control Board (FMCB) considers further action to address its operating deficit, deferred maintenance backlog, and the demands from riders for higher quality performance, once again privatization of services has come center stage. During the coming weeks, there will be ample debate on the merits of proposals to outsource ancillary services; there has also been greater focus on whether some core services of the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA) should be competitively bid to ensure higher quality service and lower costs.

In situations when there is heated discussion due to the potential impact on the interests of labor, as evidenced by the hundreds of MBTA union members who attended a rally before and during the Monday, September 12 FMCB hearing, it is instructive to take a broader view of competitive bidding and public transit services around the country.

National context

Transit service agencies nationwide have long struggled with operating costs that have been outpacing inflation and overwhelming agencies’ capacity to fiscally manage. A principal source of this cost trend is growing nominal labor costs among transit workers, which a growing body of research suggests might be explained by inevitable declining labor productivity in public transit services.

A central reason for this stagnation in labor productivity is that transit services are vastly more labor intensive than many other industries and, unlike other industries, have not experienced commensurate benefits by employing new technologies and innovations to increase productivity.

As two MIT researchers suggest in a 2015 study, labor stagnation among transit workers might be a function of “low labor mobility that prevents access to lower labor cost.” The authors explain that in cities “with a strong local economy and rising wages” — e.g. Boston — “the transit agency cannot avail itself of labor in lower cost areas, as other industries may do with capital and intermediate goods.” In the same study, the authors note that in 85 percent of the agencies examined compensation per employee rose more rapidly than the rate of inflation.

As service agencies have dealt with resulting financial difficulties nationwide, many have sought creative solutions. An increasingly popular policy proscription among these ideas is privatization. Transit agencies across the country have been increasingly looking to privatization as a channel through which to reduce growing operating costs and improve service delivery.

One specific area of strong interest is the outsourcing of bus service, which some have identified as especially prone to stagnation in labor productivity. This service area is a natural first choice for transit agencies working to rein in costs—and a number of estimates suggest enormous cost savings can be realized. A 2011 report by the National Center for Transit Research concluded that large transit systems, defined as those with 250 or more vehicles operating at maximum service, paid 40.4 percent less for purchased bus transportation per revenue mile ($6.67 per mile) than for bus transportation provided directly by transit agencies ($11.19 per mile) in 2008. More recently, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, published earlier this year, shares an estimate that local governments could achieve up to $5.7 billion in cost savings—or 30 percent of total US bus transit operating expenses—if agencies introduced a ‘full privatization’ policy.

A nationwide trend toward outsourcing of public transit services

According to current National Transit Database (NTD) data, there is a growing trend towards outsourcing in bus service. As the data illustrates, a significant number of transit groups across the country are moving aggressively towards outsourced, or “directly purchased” bus service.[1]

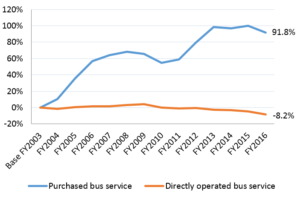

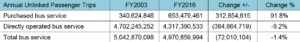

As NTD data reveals, from FY2003 to FY2016 the annual number of passenger trips provided by U.S. bus transit agencies through vendor contracts rose by 91.8 percent (see Figure 1), increasing by 312.8 million trips per year (see Figure 2). During the same period, annual passenger trips provided directly by U.S. bus transit agencies declined by 8.2 percent, decreasing by 384.9 million trips per year.

Figure 1. Annual contracted bus passenger trips increased by 91.8% from FY2003 to FY2016; agency-provided trips decreased by 8.2%

Figure 2. Annual contracted bus passenger trips increased by 312.8 million from FY2003 to FY2016; agency-provided trips decreased by 384.9 million

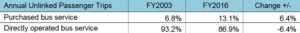

The proportionate share of purchased service trips of total bus passenger trips increased by 6.4 percent, increasing from 6.8 percent in FY2003 to 13.1 percent in FY2016. Over the same timeframe, the share of directly-provided trips decreased by 6.4 percent—from 93.2 percent in FY2003 to 86.9 percent in FY2016 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportion of contracted bus passenger trips of total bus trips rose from 6.8 percent to 13.1%.

Implications for MBTA bus service

As transit agencies nationwide shift towards outsourcing bus service, it would be prudent for the MBTA to consider the utility of adopting practices that are more in line with this national trend. This is especially true in light of the enormous costs of bus service at the MBTA relative to both the agency’s 5 INTDAS-designated transit peer agencies and the top 30 transit agencies in operating cost per revenue mile and revenue hour. According to analysis performed by Pioneer, the MBTA has an operating cost per bus revenue mile ($18.26) that is more than 27 percent above the average of the top 30 agencies ($14.34)—and 16 percent above the group’s average total operating expense per vehicle revenue hour ($181.10 compared to the top 30’s $156.13).

As Pioneer has identified in its examination of MBTA bus service and maintenance costs since 2013, a central obstruction in reducing costs has historically been the so-called “Pacheco Law”, which put in place unnecessarily rigid criteria to employ in the state’s consideration of proposals to outsource public services to non-union labor. One analysis from Pioneer concluded that the Pacheco Law has cost the MBTA in excess of $450 million since 1997.

Recognizing the opportunity to help steer the agency onto a more prudent fiscal course, the Fiscal Management Control Board (FMCB) moved to exempt the MBTA from the Pacheco Law. In July 2015, the legislature moved forward with a 3-year moratorium on the Pacheco restrictions. As the window to act on this exemption closes the FMCB must consider initiatives that will ensure the long term sustainability of the MBTA and fiscal viability of the agency.

Much of the focus of the FMCB thus far has rightly been on outsourcing ancillary services such as the cash management, fare collection and parts warehousing and delivery. There are critical reasons for the FMCB’s focus on the potential loss of up to $20 million in assets from the “money room”, according to a state report; up to $42 million in uncollected fares; and disabling, slow delivery of critical repair parts. In addition to these areas, there are fundamental reasons to extend the effort to privatize other aspects of the MBTA’s operations. Principal among the FMCB’s reasons may be the need to ensure savings that will allow the Authority to close its budget gap and invest more money into its infrastructure and core services. Of equal or greater importance to riders is improving the quality of the service delivered. Given the often unsatisfactory quality of service currently provided, that will require judicious use of vendors, as has been the case across the country. It will also require that the FMCB does not fall into the trap of creating “privatizations” which are anything but that, such as is the case of Keolis, where the company has little control over human capital and work rules and resulting issues with operational performance.

[1] The NTD was established by U.S. Congress to serve as country’s “primary source for information and statistics on the transit systems of the United States.