Book Reveals How Tax Hike Amendment Would Damage Commonwealth’s Economic Competitiveness

Punishing tax on small businesses and retirees unlikely to significantly increase transportation and education funding

BOSTON – If adopted, a constitutional amendment to hike state taxes that will appear on the ballot in November could erase the hard-earned progress Massachusetts has achieved toward economic competitiveness over the last 25 years and may not result in any additional education and transportation funding, according to a new book from Pioneer Institute, entitled Back to Taxachusetts?: How the proposed tax amendment would upend one of the nation’s best economies, which is a distillation of two dozen academic studies.

“People — even some in the media and business community — don’t understand the tax and what it does,” said Jim Stergios, executive director of Pioneer Institute. “This book explains the many forms of income it will sweep up, the real people and businesses it will affect, and the fact that, despite misleading promotional language from the Attorney General, it will likely result in little to no increase in education and transportation funding.”

A tax on small businesses, homeowners and retirees

The amendment to the Massachusetts Constitution would have a particularly significant impact on retirees and small businesses. It would affect a long list of “income” categories, including salary, capital gains (on the sale of investments, homes, businesses and other assets), dividends, IRA and 401K distributions, interest, royalties, and commissions. In any one year, should the totality of these income streams exceed $1 million, the state would increase existing income taxes by 4 percent on the excess.

“Pass-through” companies such as partnerships, limited liability corporations, subchapter S corporations and sole proprietorships are taxed via individual returns. These mostly small businesses, nearly two thirds of which are subchapter S corporations, employed almost half of all private, for-profit employees in Massachusetts in 2019.

Passage of the constitutional amendment would force many pass-through businesses to pay the new 4 percent tax on top of the existing 5 percent income tax. Subchapter S corporations, which currently pay Massachusetts’ unique “stinger tax” of up to 3.9 percent, would face a total state tax burden of up to 12.9 percent, a rate higher than large corporations pay.

In addition, adopting the tax hike amendment would give Massachusetts the nation’s highest short-term capital gains tax (16 percent) and the highest long-term capital gains tax in New England.

“[Massachusetts’ tax proposal] would impose a one-time ‘retirement tax’ on many sellers of homes and small businesses, and encourage our most productive residents to leave,” said Richard Schmalensee, former Dean of MIT’s Sloan School of Management. “[A]ll without guaranteeing an increase in spending on transportation or education.”

The book reveals just how wide a net the tax casts well beyond “millionaires.” In fact, the tax hike amendment falls primarily on households selling a family home or business to finance retirement. Nearly half of all parties affected by the tax earn $1 million or more only once in a decade; over 60 percent do so only twice.

The tax would apply to more residents every year. To adjust for inflation, the tax amendment uses the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, which has lagged well behind household income and wages in Massachusetts. State legislative salaries, on the other hand, are tied to median household income, which has risen much faster.

“Proponents call this the “Fair Share Amendment,” suggesting that it applies to some nebulous fat cat,” said Pioneer Research Director Greg Sullivan, who, with Andrew Mikula and Liam Day, authored Back to Taxachusetts? “But the fact is that the large majority of affected parties will be retirees or small businesses — families that paid down their mortgages and loans and most often never made anything close to a million.”

Fewer jobs, people and employers vote with their feet

We don’t need to look far to see the proposed tax’s likely economic impact. From 2008 to 2020, Connecticut, which is still recovering from years of “tax the rich” policies and today boasts the second highest state and local tax burden per capita (Massachusetts ranks 14th):

- Ranked 49th among the states and Washington, D.C., in private sector wage and job growth

- Had wage growth that was half the rate of wage growth in Massachusetts

- Had fewer jobs in 2020 than in 2008, while Massachusetts’ 11.8 percent job growth outpaced the nation

As Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont has said, “It’s really dumb to [raise taxes on wealth] just by the state” and doing so would “totally disadvantage the state. [Connecticut] already [has] some of the highest income tax rates in the country and we pay a price for that.”

Many large employers left the Constitution State, including GE and Alexion Pharmaceuticals, which relocated to Massachusetts. Between 2012 and 2018 Connecticut experienced the second worst net out migration of high-income taxpayers.

Among many other tax hikes, Connecticut increased its highest income tax rate from 4.5 percent to 6.99 percent between 2003 and 2018, while Massachusetts reduced its rate from 5.6 percent to 5.1 percent. Because of its lackluster economy, Connecticut could only muster 22 percent growth in the state budget from 2008 to 2020, while Massachusetts, with strong economic growth, saw its budget grow 63 percent.

“A stable tax environment, together with Massachusetts’ innovation economy, resulted in a significant rise in jobs and wages in Massachusetts,” Sullivan said. “Massachusetts’ economic growth field budget growth at three times the rate in Connecticut — generating revenue that public sector leaders could invest in public priorities like education and transportation.”

If the tax hike amendment passes, Massachusetts will have a higher top-end rate than Connecticut.

A Blank Check

Proponents claim the tax will increase public spending on education and transportation. The Attorney General is fighting a court battle to preserve that fiction, even though the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court justices made clear in a 2018 hearing on the question that legislators can really spend state revenues on whatever they want.

“Both in their brief and in response to a direct question from the then-chief justice of the SJC, the Attorney General’s Office, which was arguing in favor of the surtax, made it clear that while revenue from the tax had to be used for education and transportation, nothing prevented state legislators from reducing education and transportation funding from other sources by an equal or greater amount,” Sullivan.

That’s pretty much what happened in California. After a 2012 tax hike “to fund education,” lawmakers left in just enough of the funding from other sources to meet state-mandated minimum funding levels. Much of the money previously dedicated to education was redirected to the state payroll, which increased at twice the national average rate from 2012 to 2020.

The provision “became a funding cap, not a floor,” said California policy consultant Kevin Gordon.

During debates on the proposed constitutional amendment, Massachusetts legislators made their intentions crystal clear twice rejecting amendments that would ensure that new tax revenues added to existing education and transportation expenditures. Both amendments were rejected by 4:1 margins.

Timing is everything

The tax hike amendment has been in the works — and its wording has not changed — since 2015. In the interim, the policy environment has changed in three significant ways.

First, the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), adopted in 2017, now limits federal deductions for payment of state and local taxes (SALT) to $10,000. Prior to TCJA, the federal SALT deduction allowed those likely affected by the proposed tax hike amendment to write off a large percentage of their state tax burden on their federal tax bill. That write-off is now largely gone and translates to paying up to nearly 150 percent more in state income taxes.

Second, the vote on the tax amendment comes as Massachusetts is awash in money. The Commonwealth is generating multi-billion dollar annual budget surpluses and is trying to figure out how to spend billions more in federal pandemic relief.

“State revenues in April outpaced budget projections by $2 billion,” said Stergios. “That’s more than the state would raise through the tax hike proposal in an entire year — and it is all because of economic growth and job creation.”

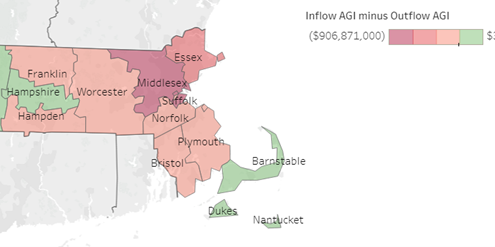

Third, the tax hike would kick in at a time when both employers and employees are more mobile than ever before. Despite doing far better than Connecticut, Massachusetts still saw an annual loss of nearly $1 billion in adjusted gross income due to net out migration, more than 70 percent of it to Florida and New Hampshire.

Prior to the pandemic, about 3.6 percent of employees worked from home at least half the time. Post pandemic, a Harvard Business School study estimates that 16 percent of employees will be telecommuters, while an Upwork survey puts the number at 22 percent.

“The rise of Zoom and remote work has made it even easier for businesses and highly skilled workers to leave Massachusetts for low or no-income tax states like New Hampshire, Florida, and Texas,” said Harvard University economist Edward Glaeser.

As Massachusetts contemplates raising taxes, state competition is fierce. Neighboring New Hampshire, which has no income tax, just voted to phase out its tax on interest and dividends. In 2021, 16 states cut income taxes; 13 more have income tax cuts in the works. In a world in which technology makes it possible to work from anywhere, the cost of living and doing business is more important than ever before.

Because it is a proposed amendment to the state Constitution, should it pass and lead to the expected negative impact on economic growth, repeal would be next to impossible.

Authors

Gregory Sullivan is Pioneer’s Research Director. Prior to joining Pioneer, Sullivan served two five-year terms as Inspector General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and was a 17-year member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Greg holds degrees from Harvard College, The Kennedy School of Public Administration, and the Sloan School at MIT.

Andrew Mikula is an economic research analyst and candidate for a Master’s in Urban Planning at Harvard University. Mr. Mikula was previously a Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at Pioneer Institute and studied economics at Bates College.

Liam Day is a leader in the non-profit space in San Francisco and a writer. His experience in Boston includes serving as a youth worker and teacher, government service at the Boston Public Health Commission, including directing Child and Adolescent Health, and Director of Communications and Strategic Partnerships at Pioneer.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute develops and communicates dynamic ideas that advance prosperity and a vibrant civic life in Massachusetts and beyond. Success for Pioneer is when the citizens of our state and nation prosper and our society thrives because we enjoy world-class options in education, healthcare, transportation and economic opportunity, and when our government is limited, accountable and transparent. Pioneer believes that America is at its best when our citizenry is well-educated, committed to liberty, personal responsibility, and free enterprise, and both willing and able to test their beliefs based on facts and the free exchange of ideas.

Praise for Back to Taxachusetts?

“The rise of Zoom and remote work has made it even easier for businesses and highly skilled workers to leave Massachusetts for low or no-tax states like New Hampshire, Florida, and Texas. This book is a must-read for anyone thinking about voting in favor of amending the Constitution to make Massachusetts less business-friendly.”

– Edward Glaeser, Harvard University

“What could possibly go wrong? The authors identify a myriad of potential unintended consequences from establishing a graduated income tax in Massachusetts. Along the way, they reveal the dynamism of the state’s economy and its people. This book is a must-read for the people of the Commonwealth at this pivotal moment.”

– Sara Johnson, economist

“Economic success is increasingly a hunt for talent. Back to Taxachusetts? asks a critical question at a critical time — namely, with remote work and wealth mobility at a historic high, why would Massachusetts choose to put itself at a disadvantage in recruiting and retaining a talented workforce?”

– Laurence Kotlikoff, Boston University

“The data presented in Back to Taxachusetts? are compelling and frightening. The public must consider the negative effects of this surtax, and the numerous examples of how it backfired elsewhere before making the same mistake here in the Commonwealth.”

– John Regan, Associated Industries of Massachusetts

“Even if you support progressive taxation, this fact-based book will persuade you to oppose Massachusetts’ surtax proposal. It would impose a one-time “retirement tax” on many sellers of homes and small businesses, and encourage out-migration of our most productive residents — all without guaranteeing an increase in spending on transportation or education.”

– Richard Schmalensee, Sloan School of Management, MIT

“Massachusetts has finally established itself as a good place to do business. This has taken a lot of time and effort. It has also produced tremendous dividends for the Commonwealth. The notion of returning to Taxachusetts is simply wrongheaded and deleterious.”

– William Achtmeyer, Acropolis Advisors

“Pioneer nailed it. This comprehensive study mirrors what I regularly faced while competing with other states for business development: Taxes matter. At 5%, Massachusetts is disadvantaged against some states but better than others. At 9%, forget about playing offense, we will be perpetually on defense as our golden egg laying geese take flight to lower cost harbors!”

– Jay Ash, Massachusetts Competitive Partnership

“The effects of tax policies and regulations on small businesses and business formation are well known. Pioneer’s study effectively lays out the consequences of the constitutional tax amendment on entrepreneurs and should be heeded.”

– John Friar, Executive Professor of Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University

“Pioneer Institute has done it again with Back to Taxachusetts? Their findings on the tax amendment proposal are a clear warning about what can go wrong when taxes are set by slogans and emotion rather than research.”

– Peter Forman, South Shore Chamber of Commerce

“Opinion leaders across the Commonwealth must read this book and understand the consequences of passing this massive tax hike. Without clear voter education, small business owners will be asking their legislators, associations and chambers of commerce ‘where were you and why didn’t you warn me?’”

– Jon B. Hurst, Retailers Association of Massachusetts

“This book reveals truths that proponents don’t want you to know. The tax ensnares unintended people, even retirees. Promised higher spending on education and transportation evaporate. Experiences from other states warn of big taxpayers leaving even faster. The more you tax an activity, the less of it you get. This economic rule may be hard for tax proponents to admit, but it’s not too hard for voters to understand.”

– Marc A. Miles, PhD, Former Assistant State Treasurer, State of New Jersey

“If you’re somebody who cares about the future of our state, this book gives you all you need to make an informed decision on the graduated income tax proposal. As the authors show again and again, the tax will wreak havoc on the state’s competitiveness and economic well?being.”

– Brian Shortsleeve, co-Founder, M33 Growth

Get Updates on Our Economic Opportunity Research

Related Posts: