Testing the Tests: Why MCAS Is Better Than PARCC

Study: MCAS Less Expensive, More Rigorous and Provides Better Information than PARCC

Authors call for state to phase out both PARCC and Common Core

BOSTON – In the wake of an apparent shift by Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell Chester making it increasingly likely that Massachusetts will update MCAS rather than adopt English and math assessments developed by the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC), a new study published by Pioneer Institute concludes that revising and updating MCAS would result in lower costs and more rigorous assessments that would provide better information about student performance.

“The research leads us to support keeping MCAS and making it an even better test,” said Jim Stergios, Pioneer’s executive director. “We are all for an MCAS 2.0, but that means pre-2011 MCAS should be the starting point for new assessments and test items, not PARCC.”

“How PARCC’s False Rigor Stunts the Academic Growth of All Students” compares PARCC, which is based on Common Core’s K-12 English and math standards, to pre-Common Core MCAS reading and writing tests. Among its many findings, the study demonstrates that PARCC fails to meet the accountability provisions set forth in the state’s Memorandum of Understanding with the U.S. Department of Education in order to qualify for Race to the Top funding in 2010.

The pre-Common Core MCAS tests were chosen in part because MCAS is now based on Common Core standards, not the state’s pre-2011 standards. Pre-Common Core MCAS tests were also chosen because of the dumbing down of 10th grade MCAS tests. For years, MCAS results mirrored state performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). In 2013, that remained true for 4th and 8th grade MCAS tests. But that year, while 80 percent of students scored “advanced” or “proficient” on MCAS 10th grade math and 91 percent on the English test, the numbers were just 34 percent in math and 43 percent in English on the corresponding high school NAEP tests.

What was at the very least a failure by the state to maintain the academic rigor of 10th grade MCAS tests is one reason why the authors recommend that MCAS 2.0 be developed by an entity independent of the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

When Chester, who also chairs PARCC’s governing board, announced his apparent shift, he cited the importance of maintaining state control over student assessments. Pioneer Institute has argued against tying the Commonwealth to the faltering PARCC consortium, which once boasted 26 member states but today includes just seven or eight largely low performers. With the number of potential test-takers in these states falling from 30 million to under five million, PARCC’s viability and ability to maintain its current pricing are in question.

The inability of students in states like New Mexico to pass tests at the level of their Massachusetts counterparts would, over time, create pressure to reduce the tests’ rigor.

The authors also dispute claims that PARCC could simultaneously determine whether students are academically eligible for a high school diploma and ensure college readiness. High school is radically different than college, and the academic demands of various post-secondary programs vary dramatically. Our international competitors use different tests for high school graduation and entrance to post-secondary education.

Despite claims that PARCC would do a better job ensuring that students are “college- and career-ready,” a recent study found that PARCC assessments were no better at predicting college readiness than MCAS—even though grade 10 MCAS tests have been dumbed down.

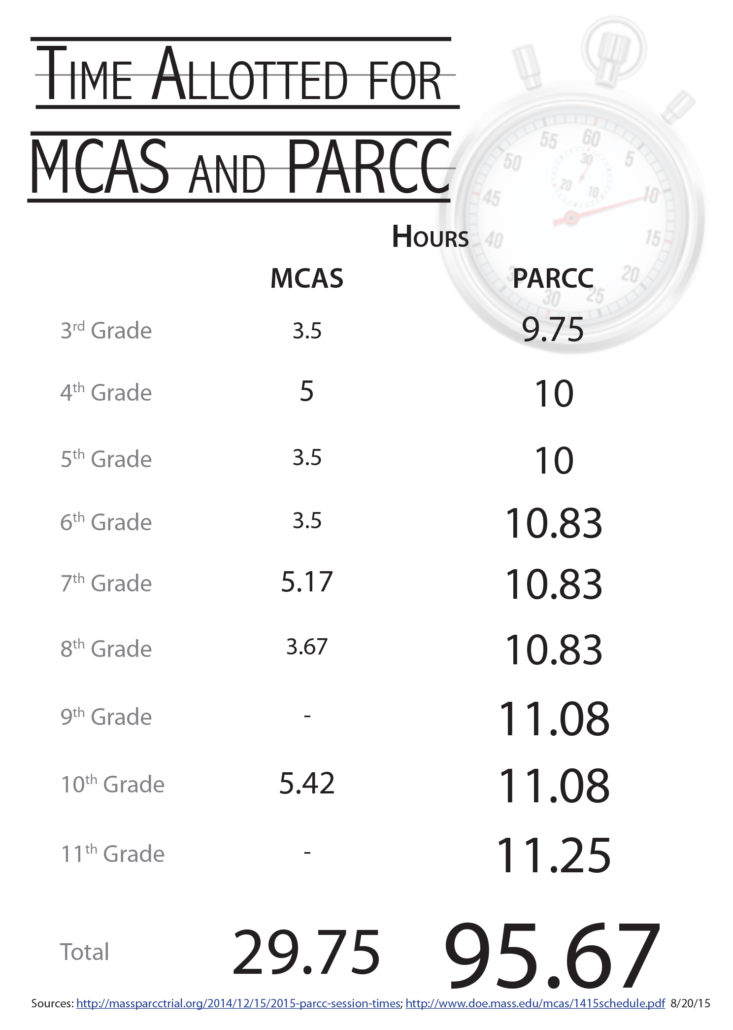

PARCC would also force schools to devote many more hours to testing, leaving less time for classroom instruction. By the time he or she graduated from high school, the average student would spend almost three times as many hours taking PARCC tests than they would MCAS assessments.

Supporters also claim PARCC does a better job of testing “higher-order thinking.” In fact, its new types of test items are not research-based and not very good. They are often difficult to navigate and what passes for testing higher-order thinking are simply multi-step problems.

At the root of PARCC’s weaknesses are the Common Core standards to which they are tied. The authors call on the Commonwealth to phase out Common Core and PARCC, and to base a revised MCAS on Massachusetts’ pre-Common Core curriculum frameworks, updated by pertinent new research.

“How PARCC’s False Rigor Stunts the Academic Growth of All Students” was written by Mark McQuillan, Richard P. Phelps and Sandra Stotsky. McQuillan is former dean of the School of Education at Southern New Hampshire University and commissioner of education for the state of Connecticut. Prior to that, he was a deputy commissioner of education and a school superintendent in Massachusetts.

Richard P. Phelps is the author of four books on testing and founder of the Nonpartisan Education Review (http://nonpartisaneducation.org).

Sandra Stotsky is professor emerita at the University of Arkansas where she held the 21st Century Chair in Teacher Quality. Previously she was senior associate commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and a member of the Common Core Validation Committee.

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.