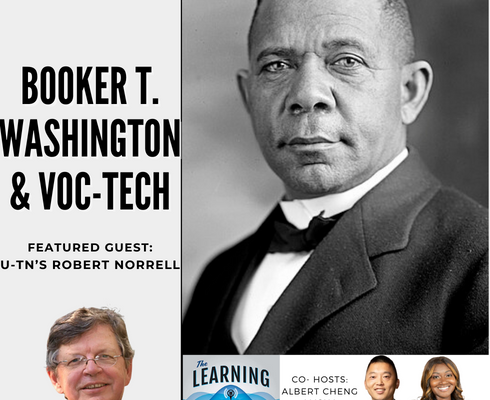

David Ferreira & Chris Sinacola on MA’s Nation-Leading Voc-Tech Schools

/in Academic Standards, Blog: Education, Featured, Podcast, School Choice, VTE - Podcast /by Editorial StaffThis week on “The Learning Curve,” co-hosts Cara Candal and Gerard Robinson talk with Chris Sinacola and David Ferreira, co-editors of Pioneer’s new book, Hands-On Achievement: Massachusetts’s National Model Vocational-Technical Schools. They share information from their new book on the story of the Bay State’s nation-leading voc-tech schools, and how accountability tools from the state’s 1993 education reform law propelled their success. They talk about the pivot from the singular focus on occupational education, to a more balanced approach that required a solid grounding in high-quality reading and math skills. They review Massachusetts’s voc-tech schools’ status as high schools of choice, and how this impacts these schools’ remarkable graduation rates, and high demand. They discuss voc-tech schools’ success at educating special needs students, who enroll in these schools at disproportionately high rates. They explore how best to close racial achievement gaps, and how voc-techs have partnered with businesses and unions alike to help place their students in careers. The interview concludes with a reading from their new book.

Stories of the Week: In New Mexico, the Governor has submitted an education reform plan, after a 2018 court order requiring statewide education reforms to address inequities impacting students with disabilities, English language learners English, Native Americans, low-income students. Has the focus on raising academic achievement pushed out physical education from K-12 schools?

The next episode will air on Weds., June 15th, with Dr. Margaret “Macke” Raymond, the founder and director of the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University.

Guests:

Chris Sinacola has more than 35 years of experience in journalism, marketing, health care, and freelance writing. He was a reporter and editor at the Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1987 until 2015. He is the author of Images of America: Sutton (2004) and Images of America: Millbury (2013) and editor of Pioneer Institute’s The Fight for the Best Charter Public Schools in the Nation (2018) and A Vision of Hope: Catholic Schooling in Massachusetts (2021). Sinacola holds a bachelor’s degree in Italian Studies from Wesleyan University.

Chris Sinacola has more than 35 years of experience in journalism, marketing, health care, and freelance writing. He was a reporter and editor at the Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1987 until 2015. He is the author of Images of America: Sutton (2004) and Images of America: Millbury (2013) and editor of Pioneer Institute’s The Fight for the Best Charter Public Schools in the Nation (2018) and A Vision of Hope: Catholic Schooling in Massachusetts (2021). Sinacola holds a bachelor’s degree in Italian Studies from Wesleyan University.

David Ferreira spent his professional career as a vocational-technical teacher, coordinator, and principal, 16 years as superintendent of a regional school district, and was inducted into the Diman Regional Voc-Tech Hall of Fame. As Executive Director of the Massachusetts Association of Vocational Administrators, he advocated for high-quality programming for voc-tech districts and collaborated with postsecondary institutions and apprenticeship programs. Mr. Ferreira received his master’s degree in Secondary School Administration from Providence College. He served on the New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) Commission on Technical and Career Institutions and the state’s Vocational Technical Advisory Council and was an adjunct faculty member at the University of Massachusetts Boston, and Fitchburg State University.

David Ferreira spent his professional career as a vocational-technical teacher, coordinator, and principal, 16 years as superintendent of a regional school district, and was inducted into the Diman Regional Voc-Tech Hall of Fame. As Executive Director of the Massachusetts Association of Vocational Administrators, he advocated for high-quality programming for voc-tech districts and collaborated with postsecondary institutions and apprenticeship programs. Mr. Ferreira received his master’s degree in Secondary School Administration from Providence College. He served on the New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) Commission on Technical and Career Institutions and the state’s Vocational Technical Advisory Council and was an adjunct faculty member at the University of Massachusetts Boston, and Fitchburg State University.

Tweet of the Week:

“Charter schools educate 7% of all public-school students, yet they receive less than 1% of total federal spending on K-12 education. As more parents opt out of traditional district schools, that imbalance should be corrected” https://t.co/G46PDtanU3

— Eva Moskowitz (@MoskowitzEva) June 6, 2022

News Links:

Jay Mathews: What happened to P.E.? It’s losing ground in our push for academic improvement.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/06/05/physical-education-classes-schools/

New Mexico’s education reform plan presented to tribal leaders

https://sourcenm.com/2022/06/06/new-mexicos-education-reform-plan-presented-to-tribal-leaders/

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode

Please excuse typos.

[00:00:00] Cara: Listeners welcome to the learning curve. This is Cara Candal reunited with my good friend, Gerard Robinson, Gerard. You had to be a way last week. We had our friend Derrell Bradford, pinch hitting for you. It was as I’m sure you heard about. Heavy conversation for the heavy times. Looking forward to, getting back together with you this week, we’ve got some great guests coming up today.

[00:00:44] Some local guys here talking about a new book from pioneer Institute. So on the whole things are looking good. How are you doing?

[00:00:53] GR: I’m doing well. I’m always glad to be with you again and glad that we can cover some ground. And [00:01:00] you’re right. It was a heavy week, last week. And my condolences to family, friends, and, others who were impacted by what took place in Texas.

[00:01:07] And we will see what people in state capitals and federal government will do. And in the interim, we will continue to plug along to help people with the learning.

[00:01:17] Cara: Absolutely. And it remains heavy even to be clear, like this is not, even the, case of you Aldi and the, so many, so many, so many other tragedies that this country has suffered in recent decades and weeks.

[00:01:29] And it was not a good weekend for folks in places like Tennessee and in Chicago. And in fact, across the country, Continue to happen. And I was no jury George, you know, I was thinking, as we were thinking about what stories we want to talk about this week one of the reasons I picked mine is because I think it illustrates the slow sometimes seemingly like justice.

[00:01:52] Dinosaur, like, I mean, I don’t know how fast dinosaurs were. I guess you’ve got to dress it part, some were quite fast, but I don’t know what the word [00:02:00] is. I’m looking here, but just like turtle, like I suppose, pace of policy change from time to time. And I think that there’s good in that and there’s bad in that, but I know a lot of people.

[00:02:10] In this country are feeling like, wow, , why is it taking so long to affect even the smallest of changes in different people follow up, have different opinions about what those changes should be. We should certainly acknowledge. But we feel that same frustration quite often when it comes to thinking about the slow pace of policy change.

[00:02:28] I like to think about it as like we think of policy-making Gerard as one of those switchback trains. I don’t know if you’ve ever written a switchback train up a mountain. It goes up a little bit and then it has to like switch back to, get momentum, to keep going up. And I, I think of policy-making like that because sometimes we’re in the business, you know, of thinking like we have a big vision, but to get people on board and aligned with that big vision, sometimes you have to push for the small tweaks.

[00:02:53] in order to get to the vision. And I think that that can be really frustrating, no matter what kind of policy you’re trying to make, [00:03:00] certainly when it comes to education. One of the things that I personally find frustrating is that often it takes generations. Often we face. Generations of children before we’re able to make policy changes in places that we, that we can feel pretty confident are based in sound data and evidence and are going to work.

[00:03:16] and today I’m thinking about the case of New Mexico and here I’ve got an article out of New Mexico. It’s entitled new Mexico’s education reform plan presented to tribal leaders. This is by. Griswold. And this is about Gerard note. Some listeners should correct me if I pronounce the name of this case, but it’s about the Yasi Martinez case, which was an adequacy lawsuit in New Mexico.

[00:03:42] I believe in 2018, we learned the outcome. And in that as in many adequacy cases in the past couple of decades, judge ruled. New Mexico students who have a right to be college and career ready. They ruled that the state was in fact failing to meet that [00:04:00] obligation. We’ve seen adequacy lawsuits in your home state, my home state in many places across this country, often it has to do with school funding often.

[00:04:07] It has to do. Instituting new standards that kids are going to meet. But what that means is that the state has to take action, right? The onus is on the state because most of the time states have constitutional think. All states now have a clause in their constitution, giving them authority for education.

[00:04:21] In many states, , define what it means to have right to an education in their state constitution. So under this case from 2018, It became clear that action needed to be taken in, the judge in the case called out, several areas. This is reminding me as I keep talking about a Boston public schools, several, several areas in which the state was really failing students.

[00:04:44] Those areas where they were failing students of color to help them achieve at the levels that they needed to failing, to help ELL students. And that includes. Native students of which there are many in New Mexico and Hispanic students. and the judge said that, you know, this was all in [00:05:00] violation of the state’s constitution called for high quality.

[00:05:04] pre-K called for culturally linguistically relevant education, smaller class sizes. All of the things that we can think about smaller class sizes, I don’t know the data on that don’t necessarily bear out, but you can see that Charge to make reform. And now as New Mexico, Lurches, it sounds like is the best word towards reform.

[00:05:24] You know, local stakeholders are expressing some concerns. And with this article really points out is that new Mexico’s tribal leaders are really expressing concerns about the extent to which the state is meeting its obligation to serve native American students and to consult with the community about what the community’s needs are.

[00:05:46] So, , native American leaders. In that state are saying that the state, while it’s looking at this quote overhaul after decades of neglect and underfunding that affected people with disabilities, those learning [00:06:00] English, native Americans, we can talk about underfunding. I think you and I are often in the camp of like, it’s not all about the money people, but when it comes to native American education.

[00:06:09] And honestly, when it comes to the history of what this country has done to native Americans And tribal schools and other places I think there’s a pretty good argument to be made that sometimes funding does make a very important difference, but tribal leaders are concerned, concerned.

[00:06:26] I’ll say that the state department of education is not taking its recommendations. and even pieces of legislation that have been passed in recent years. Seriously enough, what they’re pointing to is the quote unquote. Piecemeal inclusion of what several different native American tribes got together and offered what they’re calling a tribal remedy framework.

[00:06:50] in some of those, some pieces of that framework were passed as part of a legislative package. But the state, according to these leaders is taken a really long time, [00:07:00] getting those things rolling and getting. In motion and the tribes are also calling for more local control, local control. They say where we are quote the creators, the authors, the founders of the education, that’s going to help improve.

[00:07:15] Outcome. One thing that they’re calling for in terms of local action and local authority is they want the ability to leverage teacher training colleges and tribal colleges to create teacher pipelines that put. Native American teachers into classrooms, especially in native American areas and serving native American students.

[00:07:37] So anyway, I found this to be a really interesting article because again, it demonstrates sort of that lurch back and forward that is policy making. And that even when, you know, a court can say something, we know this from brown V board, I mean, it took two decisions to get states to take action, right?

[00:07:53] A court can say something that doesn’t mean that the action is going to be taken. And that doesn’t mean that the. Are going to be [00:08:00] implemented. This article also made me think a lot about this concept of local control. Sometimes I think we use local control as a catch all term and that the stakeholders that people think of like parents and on the ground leaders in this case, tribal leaders.

[00:08:14] aren’t necessarily represented even when decisions are made locally, sometimes other local stakeholders, the loudest voices in the room that really represent larger interests, but frame themselves as local really in the driver’s seat. But I think that this is. To watch.

[00:08:30] And certainly there’s a lot of change needed in New Mexico. We’ve seen several promising programs like a universal ESA halted there in recent years. But I’m going to keep my eye on the state of New Mexico. And I’m going to keep fingers crossed that the pace of policy change, even as key personnel in that state’s department of education are dismissed or turnover that the pace of policy change can not only ramp up, but can ramp up in a.

[00:08:56] That is going to be good for kids. So [00:09:00] as a former state chief Gerard, I know that you, at times must have been incredibly frustrated with the pace of policy change and implementation. So I’d really love your take.

[00:09:09] GR: I was an advocate for many years before the state level work, and I was frustrated with the level of change then, and then once inside.

[00:09:18] Being a part of the sausage making, they were challenges. We know that a lot that we want to see in schools that we want to see take place. A lot of that is really driven by political will and at times outside influences. So think about the pace of school choice reform over the last 24 months. It’s not as if we didn’t have school choice legislation, model legislation.

[00:09:45] It’s not as if we didn’t have that. It was COVID and the response of families and a very interesting coalition of interests that came together that just moved that forward. You mentioned brown V board of education families have been pushing, [00:10:00] for example, in your state of Massachusetts going back to the 17 hundreds.

[00:10:04] Moving forward to the 18 hundreds pushing for better schools. And yet you don’t really see those kind of changes into the fifties, sixties and seventies in Boston. A lot of that with political will, you’re also right about progress. I mean, president Obama said that progress is. Always a straight line or a smooth path.

[00:10:22] So yeah, so personally I’ve seen it two different worlds. One thing that will be interesting to see is what local control looks like in New Mexico, in Virginia, where I live look control is real. And we know that there’s also something called a. Which said that localities are really creatures of the state.

[00:10:42] And that may be true, but you have states that have strong local control. And so I don’t know a lot about new Mexico’s law, but it would be interesting to see I’m a fan of getting more native Americans or the terms they use to call themselves locally in Mexico. I love to see more of a pipeline. We know that having [00:11:00] an African-American students have African-American teachers uh, has got a positive.

[00:11:03] I would assume that there’s no difference with the students native American students as well. So I will follow this. The fact that it’s in the courts is a good thing. It will put some pressure on the legislature, but that’s going to be one to watch because we have, when we talk about students of color, We often overlook native Americans is often black and Hispanic at times when politically necessary.

[00:11:27] We say Asian students, and even then we desegregate sometimes Chinese and Japanese and Indian students away from mung and others. So we will see how this plays out. It was a great story. My story isn’t from any state, it actually is about all states. And it’s an article written by Jay Matthews. Who’s been a, guest of ours here on the learning curve is for the Washington post.

[00:11:48] And the title is what happened to physical education. It’s losing ground in our push for academic improvement. And so Jay starts off by saying he was a poor athlete and he. Well, he didn’t [00:12:00] prefer having anything to do with PE classes. And when many of his classmates had shared the same view, well, given his, , decades of research and write on education, he’s reached a point where he says, well, I think we’ve got to a point where our anti PE bias has come.

[00:12:18] To rule our education system. And so he bases that not only on his research, he’s talking about a new book by Claire Nader and it’s called you are your own best teacher sparking the curiosity, imagination and intellect of tweens. And she’s a social scientist. She took a look at. Where are we as a nation with PE?

[00:12:39] And so she said, you know, these days only 4% of elementary schools, 7% of middle schools, and 2% of high schools have daily PE the entire school year, 22% of schools have no PE at all. And so she went on to looking at what happened. He did the same, and they identified that [00:13:00] basically our push for. Achievement and testing began to push.

[00:13:06] The need for PE as we push for more reading, more mathematics science and other subjects. But there’s also a money dynamic. So you have Terry drain, who is the president of shape America. She says when money gets tight, E one of the first things to go, I’ve seen that both as an advocate and as a professional in education, even at the local level, when I worked for DC public schools.

[00:13:29] And so others were saying the same thing. I mean, it’s not new. By 2007, the Robert Wood Johnson foundation report identified only 36% of students were doing the recommended one hour of physical activity a day and 30% participated in a sport on a regular basis. And so the article goes on to say, listen, if you want to do something less, Good use of what we have for resources.

[00:13:57] And then you have Ken Reed policy [00:14:00] director of the sports performed project league of fans. And Ken noted that type two diabetes was once considered an adult disease. However, you now have young. Who have type two diabetes. And so people are coming to the case and, , read even one step further and said, a 20 minute jog around a school building will do more to improve test scores than 20 extra minutes of prep for the tests.

[00:14:25] And so there’s some really good information to take a look at here. And so what I want to do for our listeners is to put the. 2022 conversation in historical context through the lens of policy because physical education, many of us may not know it’s one of the few bipartisan issues going back to the 1950s where people came together.

[00:14:47] in Washington DC to try to do something. And so I want to give you just few examples. And so you go back to the Dwight the Eisenhower administration, and there was a report published in [00:15:00] 1953 in the journal of the American association for health and physical education and recreation. And the title of the article is.

[00:15:08] Muscular fitness and health. And it was coauthored by Dr. Hans Kraus and Bonnie Pruden. And it sounded the alarm for the nation because they identified the poor state of health of the youth in the United States. Well, two years later, another report was published in the New York state journal of medicine.

[00:15:27] And it based its conclusion on a test that was given to approximately 4,400 students between the ages of six and 16 and public schools across the United States. And to approximately 3000 European students in the same age range and Switzerland, Italy, and Austria. And what they found out is guess what American children compared to the European counterparts were not doing well.

[00:15:51] And so we often find that when it’s time to compare ourselves to others are being challenged by others. We’ve decided to take a national stand. So [00:16:00] June, 1956, president Eisenhower creates the president’s council on youth fitness setting in place, what future presidents for Kim, all the way up to buy it and would use to support physical education.

[00:16:13] When John F. Kennedy moved in, he supported it, but he made one additional change by making sure in his executive order that it wasn’t just focused on children between. Five to 12, but he wanted to expand it to all children, but he also listed as one of the objectives in the executive order, enlisting the aid of citizens and civic groups and others to be involved so that all the owners would not be placed on schools.

[00:16:38] When Johnson was president, he did the same thing. He kept everything in place. Plus as a good Texan in a big sports state, he added sports to the title. Well, you fast forward through a number of presidents who supported the program and you get to Barack Obama he supported what previous presidents had done, but he did something different in his executive order.

[00:16:59] He changed the [00:17:00] names sightly, and it became the president’s council on fitness, sports, and nutrition. The first one, add in nutrition piece in part driven by first lady, Michelle. Who believed that health and nutrition had to be a part of the conversation. Once president Trump was in office he continued with the momentum, but also made a push to create a strategy.

[00:17:21] Currently president Biden and his executive order that is going to be in place from now until September 30th, 2023 continues to move forward with that. So when we talk about PE and we talk about. We have to know that again, this debate is pretty old. I’m looking at a 1993 article in education.

[00:17:42] We’re in 1987, there were at least 42 states that had some physical education instruction. By the time the article was reported or published in 1993, there were at least 46 states, but there are challenges then. And an organization that we talked about earlier shape produced [00:18:00] a, survey of physical education requirements in 50 states.

[00:18:03] And they identify that 25 states require one year fiscal education and it moves. Well, that was 1993. I’m looking at the shape of America, executive summary for 2016 and nearly all 50 states have met have set standards for physical education, but still there are some discrepancies, many states require physical education teachers to meet professional standards requirements.

[00:18:26] Others do not some states for example, 31, a lot of activities as substance. For a fiscal education credit that is rubbing some advocates for PE the wrong way, because they’re saying you need PE for physical education. They have to have nothing to do with academic achievement. And we have nothing to do with sports.

[00:18:45] Not all children are gonna play sports, but they need PE. For their physical wellbeing. So, I am with Jay that we need to pay attention to physical education. I defer that I don’t believe [00:19:00] that it was solely pan for the sake of student achievement student even. Physical education can go hand in hand, but it is something we need to pay attention to because I saw firsthand at the state level what obesity was doing to young people and the health care costs it will have on local communities.

[00:19:19] Once those young people turn 21 and in many times become dependent upon the state for health care and.

[00:19:28] Cara: I think of it as the brain, body behavior connection Gerard, because in my house, my children know that mommy doesn’t get her one hour of exercise in the morning. Like don’t cross me. Here’s the other thing I will say.

[00:19:41] We also need to think about one of the things I’ve learned from my kid’s school. Thank you very much is that you can integrate physical activity and movement throughout the day, the dedicated hours. Fantastic and important as is recess before. When I have an eight year old boy when he gets a little out of hand, my school has a curriculum that they [00:20:00] call lift heavy things, and they find that if they give the kid a task, like, Hey, walk this ream of paper down to the office, nothing that’s going to hurt themselves.

[00:20:08] Right. And get, the wiggles out a little. That there are up and down stairs are doing this stuff. They come back, they’re calmer, they’re engaged. So I love that article Gerard and boil boy, do I love physical education? I used to love that presidential physical fitness award. That was president Reagan though.

[00:20:24] So we’ve got to bring in our fabulous guests. We are going to be speaking with Chris Sinacola and David Ferreira. They are co-editors of Pioneer’s new book, Hands-on Achievement, Massachusetts’s National Models Vocational Technical Schools. We’ll bring them in right after this.[00:21:00]

[00:21:35] Learning curve listeners. So pleased to have with us today, David Ferrera and Chris Sinacola. They are co-editors of Pioneer Institute’s new book “Hands-On Achievement: Massachusetts’s National Model Vocational Technical Schools.” David Ferreira spent his professional career as a voc-tech teacher coordinator in principal.

[00:21:57] In 16 years as superintendent of a [00:22:00] regional school district, he was inducted into the Diman regional voc-tech hall of fame and Chris Sinacola. Also, I would have to say editor of, one of my books has more than 35 years of experience in journalism, marketing, healthcare and freelance writing. He was a reporter and editor at the Wooster.

[00:22:18] Yes. If you’re from Massachusetts, you don’t have to say that it is not Winchester, Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1987 until 2015. Gentlemen, welcome to the show.

[00:22:29] 2: Thank you for having.

[00:22:32] Cara: All right. Well, we’re happy to have you, so I’m going to throw the first question out and then , we’ll see who answers, but here we go.

[00:22:38] So as both of you know, well, under the 1993, Massachusetts education reform act, the state has experienced historic gains, a NAPE reading. While remaining the only state that’s internationally competitive and math and science. The naysayer in me has to remind folks that we are backsliding. So let’s not pat ourselves on the back too much, but can you all talk about [00:23:00] how your new book tells the story of the bay states nation leading voc-tech schools and specifically how it relates to the accountability tools that we were given under the Massachusetts education reform act?

[00:23:14] 2: sure I’ll, give that one on shot. Kara. First of all, thanks very much for having us. This is a great opportunity and we’re really glad to share what we, can with the audience. The masters is education reform act was of course a watershed in state history. And I think a couple of surprises emerged.

[00:23:30] One was that initially the vocational technical community was actually rather not hostile exactly, but they gave it a, mixed reception. There was a lot of opposites. And as we write in the concluding chapter to the book few doubted the abilities of voc-tech students, rather, they objected to what was widely seen at the time as a mismatch between testing and curriculum.

[00:23:51] So there was that concern that, not set up to do this kind of high stakes testing, so why should we be subject to it, but what happened? And that was the first [00:24:00] surprise is that the voc-tech community responded. Really really well. they realized that there’s no way we’re going to get out of this.

[00:24:06] We have to face it. They did. And the strength of their model, that 50% of time in shop and 50% of time in academic classes really came out and showed its value because they’ve achieved remarkable results. The knowing that the challenge they’ve continued to meet the challenge. They built and sustained strong partnerships with business communities throughout the state.

[00:24:30] And real key to this, I think is the mentorship aspect, that mentality that has shop teachers working with the same group of kids, the same 10 to 15 young people every other week for hours at a time. And that really makes a difference in their lives. And I think the other surprise that came out of mirror is that everyone expected.

[00:24:50] And I think the intent was that the district public schools and the charter schools would learn from one another, but the dark course here has been the voc-tech community, [00:25:00] which has soared ahead even while the other schools have made significant gains, but remain in an uneasy relationship, whereas voc-tech has kind of taken the lead.

[00:25:09] So it’s been great to see.

[00:25:10] GR: So David, let me go to you and stick on the same subject of the 1993 laws. So I’m a California guy and had a chance to watch some of this from afar, but your state was very strong on occupational education at the same time, early on, struggling with. You graduated, proficient industry credential, plumbers and carpenters, electricians auto repair persons and medical technicians, and was require that the students also have a solid grounding in reading and math.

[00:25:39] Talk to us about what your state did in moving voc-tech schools to not only keep the strong vote tech side, but also making sure that academic subjects and career and Catholic education were wedded in a way that made a lot of sense.

[00:25:52] 1: Well, thank you for the opportunity as well. would say one of the big reasons is we did not lose [00:26:00] focus on our mission and our mission is to prepare students with occupational skills for employment, and at the same time, the ability academically and socially.

[00:26:13] To have a successful life in whatever career path they choose. But occupational education in Massachusetts actually started more than a century ago with industrial schools or occupational schools, particularly in the large urban areas. And back a hundred years ago, the scheduling a time was much different.

[00:26:38] we would provide students with one third hands-on instruction and their vocational area. One third of their time learning the related theory to that trade. The related mathematics needed to succeed. And lastly the ability to read blueprints and. It was specific to [00:27:00] those particular occupations, but then with the ed reform, as Chris had mentioned, we now have to spend about half of our time in the vocational setting, including the related theory, math, et cetera, and the other half of our time in academic instruction.

[00:27:18] So we developed competence. Academic competencies that were included in the state frameworks for vocational programs. And there are 45 different ones across the state and these academic competencies parallels exactly the requirements. For a competency determination from MPS. So we were teaching our theory, but emphasizing those components that would still provide the occupational experience and the technical skills.

[00:27:53] So that needed to be employed down the road. So we were trying to do two things at one time we were [00:28:00] teaching in theory. Academic concepts in an applied setting. And we would teach things like the pipe Agrian theorem and carpentry, but in a way of trying to relate it to the building of rafters and the angles of those rafters in that particular post and beam construction.

[00:28:20] So it was a , practical way of using the academic standard. But applying them to each individual, vocational technical.

[00:28:29] Cara: have a question for Chris actually in Chris, you and I have spent a lot of time thinking about schools of choice together. And of course, here in the bay state voc-tech schools, our schools of choice, and many times they are the most competitive schools in the community. Meaning they have very long.

[00:28:46] Was in, in some communities it’s charter schools and voc-tech schools are the ones that families really are clamoring to get into. So can you talk about, I’ve got two questions here. Talk about the choice, autonomy aspect and how [00:29:00] that’s led to these great results. But also I’m really curious to know about.

[00:29:04] The kinds of programs that students are clamoring to get into and the extent to which they correlate, for example, to high demand, high wage jobs. So like, kids go with.

[00:29:16] 2: Well, the first question you have, there is the keyword is really choice because the mass education reform act did create charter schools.

[00:29:25] And just as with charter schools, students who go into vocational technical education are making a conscious choice. They are not going to the default school in their community. They’re saying I want Something that’s going to engage, my mind and my hands and my brain in every way.

[00:29:41] So we’ve seen the exact same phenomenon unfold at charter schools, really, in a way, as we’ve seen unfolded voc-tech schools where students who choose a particular kind of education are invested in ways that they simply aren’t or might not be if they go to their local public school[00:30:00] While the Massachusetts model of voc-tech education, that 50% of your time in shop, 50% of your time in academic class is not widely shared around the country.

[00:30:10] The charter model is far more familiar to many states, so it’s hardly surprising that we’ve seen the benefits that follow from that. I mean, a student who gets up each day and is excited at the prospect of going to school essentially. To what they see as a job in many cases, and often is a job when they get their co-op experience, that student is going to be more motivated.

[00:30:32] There’s every incentive for them to show up and far less reason if any reason at all, for them to stay home or take a day off, much less drop out. And we’ve seen that born out in the statistics. For example, what’s the technical high school had a dropout rate of 4.7. In 2003, 2004 school years, that was just two years prior to the opening of the new school near Greenhill park where the business community is heavily invested in [00:31:00] support of that institution.

[00:31:01] 10 years later, their dropout rate was 0.5%. It’s an extraordinary record. And even though all drop rates across Massachusetts have declined and all. Voc-tech still remains ahead of the comprehensive high schools. And we see another natural by-product of that, which is high graduation rates. We have schools we spoke with who reported zero dropouts and 100% graduation rates.

[00:31:28] It’s an amazing. For any school and really not surprising when you consider the history of it. On the other question you have, what fields are they going into? The schools in Massachusetts? And I think David can speak to this a little bit more than I can have the autonomy and flexibility to change their programs.

[00:31:46] There’s something like 45 different programs. And if something like a home economics, a homemaking is no longer in Vogue or necessarily are in demand. They will drop that program over the years. And they’ll add things like audio, visual[00:32:00] radio and TV production, computer aided design, and so forth. So because they have these advisory committees at each school and they are really, really plugged into the business community.

[00:32:11] They have their finger on the pulse of that community. They know exactly what the job needs are and how to meet them. And they’re doing a fantastic job.

[00:32:19] GR: David. Chris said something really interesting about dropout rates and I’ve got a particular interest in working to support students with special needs and at the national level students with special needs, the enrollment rate is 12%.

[00:32:32] And your state at 17% while within Massachusetts volt tech schools along the averages, nearly 30%. I mean, that’s just incredible. Could you talk about how voc-tech. Goals have effectively serve students with special needs while also maintaining a very small dropout rate for the population?

[00:32:51] 1: Certainly uh, I think that that percentage is sometime to see being too, because when we talk about dropout rates and the [00:33:00] low 0.6% overall for the regional voc-tech schools, for example, that includes.

[00:33:07] 30% in some cases that our special needs population. So it makes those much lower overall dropout rates, even more significant. And I think a lot of. Comes into the concept of a small learning community. We have students in vocational technical programs that are with three teachers for their entire four years.

[00:33:34] They don’t have different teachers every year. They have the same teachers every year who teach their specific part of the trade, but they’re all in. Family. And we have a strong sentiment that that is really a powerful tool. It’s powerful because they get to know the student well beyond their physical or academic ability.

[00:33:59] To know [00:34:00] the student as a person and they become a family. The entire group becomes a family and there’s a lot of care and concern within each student from student to student and certainly from instructor to student. And I think that’s one of the big keys, these small learning environments, and that if you think about.

[00:34:21] 50% of the time is in a vocational program. I’ve there four years in high school. There were three teachers, all four teachers, depending on the number of students in the program for half of their high school education, you don’t get that kind of. Understanding between student and teacher concerned about student and teacher and the family implications that come along with it, unless you’ve got this very, very tight arrangement and we’re teaching in a hands-on experiential pedagogy where we’re relating [00:35:00] everything we teach.

[00:35:01] To an occupational career path. And I think that’s very helpful to many of the special needs students, because they can understand where this is going to take them. Chris kind of alluded to that, that they have a goal in mind. They have a job coming in mind and many of them go out into cooperative education, where they spend all of their senior year shop, time out in the field, working for money.

[00:35:27] With a real employer, who’s overseeing their, work ethic and their work style. So I think those are the two things we’re developing these competencies, but we’re developing them for special needs students, especially in a very small learning and.

[00:35:45] Cara: Well, so Chris, I want to kick it back to you for a minute, because I know you as a history guy in many ways.

[00:35:51] So the book includes an introduction by Dr. Jackie Moore on historic earliest 20th century debate between Booker T [00:36:00] Washington, who favored voc-tech schools and web Dubois, who advocated for the liberal arts. Both of which it seems are pretty good and could coexist, but can you talk about. The lessons from that debate.

[00:36:11] And I’d also love if you could give us a few more examples from places like Worcester, where president Obama and Colin Powell both spoke, and even, in a place like Springfield, mass, which has long, had issues with schools, but it’s both Texas.

[00:36:25] 2: Well, both Worcester and Springfield have done extraordinary work.

[00:36:29] And in fact, one of the chapters is devoted to explaining how both of those communities took what were aging in some ways, fading and struggling vocational schools and remade them both physically and also revolutionized the way instruction was done and how they thought about it. And both have been extraordinary success stories and are now in high demand.

[00:36:51] that makes a great chapter in and of itself. And as for Dr. Moore’s introduction, one of the real pleasures of working on this book was doing some of the [00:37:00] research and background learning. I was familiar with the boys, his book, the souls of black folk. I had not read a Booker T Washington’s up from slavery, his best known work, but I had the chance to, to read both in working on this and both of these men.

[00:37:14] Absolutely pivotal and inspirational figures in American history and in the history of education. I recommend them highly to everyone. In 1895 Washington gave an address in Atlanta and he declared and I quote, no rings can prosper until it learns that there was as much dignity in killing a few.

[00:37:31] As in writing a poem, it is at the bottom of life. We must begin and not at the top, nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities. And that was kind of responded to by the boys in his 1903 essay, the talented 10th. And he wrote I would not deny or seem to depreciate them the slightest degree.

[00:37:50] The important part industrial schools must play in the accommodation of these ends. But I do say an insistent. That it is industrialism drunk with its vision of success. To [00:38:00] imagine that its own where it can be a column. Without providing for the training of broadly cultured men and women to teach its own teachers and to the teachers of the public schools.

[00:38:10] So they had this debate, it went on throughout their lives. And I hope that I don’t think it divided them so much. And I think that sometimes the public got the wrong and question that they were mutually exclusive goals and they certainly weren’t, they were coming at the same. From different angles.

[00:38:27] And there was probably a lot more agreement than disagreement in their position. And that serves really as a model for what vocational education can and should be and what Massachusetts has made of it, taking that practical sense and adding to it some real rigorous academic achievement and the results are marvelous.

[00:38:46] And they’re getting better.

[00:38:47] GR: David, can you provide us one example? Where you’ve seen a good partnership between voc-tech school of business or a union to ensure that graduates succeed[00:39:00] in school, as well as the workforce.

[00:39:02] 1: I think we certainly can do that. And. Examples of that. But I would like to say first is that this is a natural match.

[00:39:11] If you go all the way back to a hundred years ago, industrial schools or occupational schools were for the purpose of building industry and training employees. And that’s one mission that still exists today. And actually statutorily, we are required to have advisory boards. For each of our vocational technical programs that have to meet in public two times per year.

[00:39:41] And the composition of that committee would include people from business and industry, union representation, post-secondary education, a student, a parent, and mass hire representation. So we have all of the things. Meeting twice a year and they’re [00:40:00] looking at curriculum, they’re looking at the equipment and equally important.

[00:40:05] They’re advising our teachers what is changing down the road? How is the field of what are the competencies that kids use and also these advisory programs. So we’re not looking for example, a down on the south coast of Massachusetts, the type of welding that takes place is five different. In other parts of the Commonwealth and welding is a big industry down here, but in a different way because of the Marine and fishing industry that we have down in the greater new Bedford area.

[00:40:40] So it’s this kind of thing. We provide them employers. We provide them students that they can bring on for paid employment during the senior year in cooperative education. And they get an chance to evaluate how successful they feel their students are going to be. We have [00:41:00] companies that have been donating as a result of their affiliation.

[00:41:04] Supplies and equipment to the vo-tech schools. And I’m talking $70,000 worth of equipment that the electrical program at old colony vocational received from a company that’s not in the south coast in greater new Bedford book, another south coast. Vocational technical school, who’s involved with Griffin electric and Griffin electric has provided thousands of dollars in equipment and hired hundreds of employees from that school.

[00:41:35] So it’s. A win-win situation for both sides, but what makes Massachusetts unique, I think is that the statutory requirement?

[00:41:44] GR: Thank you. Well, Chris, I’m going to turn it over to you to close us out with passage of your choice from

[00:41:52] 2: your. Sure. Thank you. All right. Yeah, David made a good point and it’s there’s a lot of hard work involved in this to [00:42:00] keep the book tech community on track.

[00:42:01] And there are a few warning signs here and there that may be changes coming in some ways and, and the community will have to resist that. And the reason I think they will succeed is is found in this passage from chapter three, which talks about the low dropout rates. I’ll just be two paragraphs. Unlike teachers at comprehensive high schools whose contact with students is limited to a class period.

[00:42:23] And perhaps after-school programs, voc-tech students are with 10 to 15 students all day, every other week. These adults develop mentoring roles and are alert to subtle changes that may signal the beginning of an issue that would could cause the students drop out of school. The instructors are eyes and ears said she’ll Haredi, former principal of Worcester technical high school.

[00:42:41] And now superintendent at Monta. Two-cents what a student goes into crisis or has. They are the ones who hear that firsthand and are able to assist or to redirect the student. And I think that quote just goes to the heart of that vocational educational model, the caring and the hard work and the dedication that these communities exhibit every [00:43:00] day.

[00:43:00] GR: Well, Kara and I thank both of you for joining us for this conversation. Thank you for the book. Thank you for the many hours of research that goes into an endeavor of this kind. I can say as someone who grew up in Los Angeles, in the 1970s with two parents from the south there was a time when the term voc-tech was cold for other people’s children.

[00:43:23] It was often cold for the kids who weren’t smart. It was cold for those kids who only can work with their hands, not with their brains. And what you’re showing is that head brain, heart, vision are all together and you should provide for Willie wonderful. statistics to back that up and as someone who supports the idea that we need to give students a platform that could lead to a four-year college or two year college public or private or for-profit or one that goes directly into the workforce or create entrepreneurship um, just from multiple paths.

[00:43:56] And I’m so glad that Massachusetts remains [00:44:00] a Let’s just say a city on a hill, metaphorically speaking as relates to voc-tech. And thank you so much again for what you do and look forward to talking to you in the future.

[00:44:10] 2: Well, thank you so much.[00:45:00]

[00:45:06] Cara: And listeners as always, we leave you with a tweet of the week, this one from friend of the learning curve and former guests, Eva Moskowitz, she says charter schools educate 7% of all public school students. Yet they receive less than 1% of total federal spending on K to 12 education. As more parents opt out of traditional districts.

[00:45:27] That imbalance should be corrected. I feel Gerard. Like we have to keep reminding our listeners of the fact that charter schools are doing good work and they’re often doing it with less and they need more time after time Gerard, next week we will be back together again. And we’ll be speaking with Dr.

[00:45:43] Margaret Macke Raymond. She is the founder and director of the center for research and education outcomes, credo at Stanford university. Gerard Robinson until then please take good care of. You too. All right. Talk soon.[00:46:00]

Recent Episodes

Hoover at Stanford’s Stephen Kotkin on Stalin’s Tyranny, WWII, & the Cold War

Johns Hopkins’ Ashley Berner on Educational Pluralism & Democracy

39th U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky for National Poetry Month

U.S. Chamber Foundation’s Hilary Crow on K-12 Civics Education

UCLA’s Ronald Mellor on Tacitus, Roman Emperors, & Despotism

Tufts Prof. Elizabeth Setren on METCO’s Proven Results

Pulitzer Winner Joan Hedrick on Harriet Beecher Stowe & Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Dr. Adrian Mims on The Calculus Project & STEM

Yale University Pulitzer Winner Beverly Gage on J. Edgar Hoover & the FBI

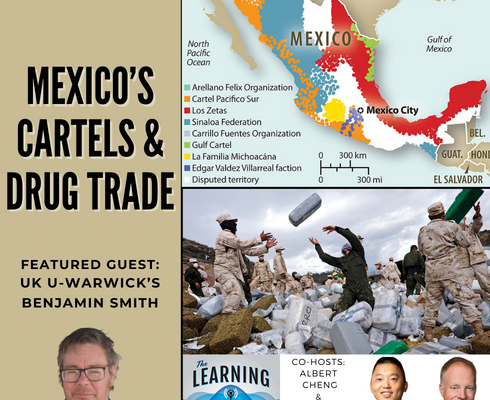

UK U-Warwick’s Benjamin Smith on Mexico’s Cartels & Drug Trade

DFER-MA’s Mary Tamer on MCAS & Teacher Strikes