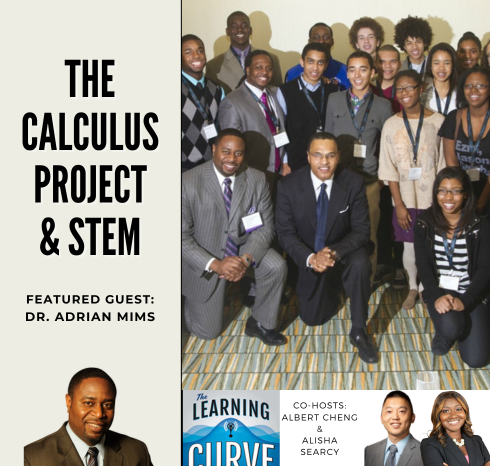

Dr. Adrian Mims on The Calculus Project & STEM

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Adrian Mims

[00:00:00] : Alisha: Welcome back to The Learning Curve podcast. I’m your co-host this week, Alisha Thomas Searcy and joined by my friend Albert Cheng. Welcome Albert.

[00:00:42] Albert: Hey Alisha, good to be with you this week as always. Hope you’re doing well.

[00:00:43] Alisha: Oh yeah. I hope you are too good. Absolutely doing well. I’m excited about our interview today and I know you are. Mr. Math expert.

[00:00:54] Albert: Well, expert. I don’t know if that’s being too generous, but certainly love math.

[00:00:59] Alisha: It’ll be fun for sure. So let’s jump in with our stories of the week. This week I chose the story entitled “anti school choice.”

[00:01:08] Alisha: Texas Republicans beg public schools to rescue them. Now, if that title was not enough, the story itself is: Eyebrow raising, I’ll just say. I know that we don’t get too much into politics on this podcast, so I won’t go down the political road, but I will say, because it’s important to me to note that I’m not a huge fan of some of the policies of Governor Abbott in Texas not related to education, but some other things, so I have to go on record for saying that, but I have to tell you, this is very interesting, Albert, so in this article, it talks about the fact that there’s an election today, actually.

[00:01:47] Alisha: Their primary is happening in Texas and this Republican governor has essentially selected 10 of his own members of his party who are in the House to [00:02:00] primary them or to at least support. Opponents who are in their primary solely on the issue of school choice. And so why is this interesting?

[00:02:09] Alisha: As a Democrat, I have seen this happen on my side of the aisle. I have certainly been primary because of my support of public school choice in particular. I have not seen this with Republicans, and I certainly have not seen a governor. Go as far as to work against 10 of his or her own members solely on school choice.

[00:02:31] Alisha: And part of me is a little bit intrigued by this because, I feel like if you’re going to stand up for kids, if you’re going to stand up for empowering parents and you recognize that part of that standing up is electing people who are with you, I think that that’s a very powerful statement.

[00:02:47] Alisha: At the same time, it is a little bit troubling to have a governor. Again, opposed 10 of his own members on one issue. And even though public school [00:03:00] choice in particular for me is a really big issue and something that I, I’d be willing to make a lot of political risks around, I’m not sure if it sets the right example that if you disagree with your party on one particular issue, we should open the floodgates to allow folks to primary you work against you. So that’s one very interesting piece of this story to me. The other interesting piece is it’s very odd when you hear that Republicans are trying to get the teacher’s unions and public school employees to help them on their…

[00:03:34] Alisha: Political campaigns. Not only is it illegal right to get school personnel to work on your campaign or in particular to campaign to them, asking them to vote within the Republican primary to protect public education, which is what some of these sitting legislators are doing. But certainly, there’s got to be a line right between the electoral politics and what’s happening in public education, but politically, it’s also interesting [00:04:00] because generally, you see Democrats more aligned with teachers unions and public schools.

[00:04:06] Alisha: So this whole thing is quite interesting. I cannot wait to watch CNN or Fox, whatever we need to watch tonight to find out the fate of these 10 legislators. Because if in fact this governor is successful it’s going to set off a firestorm. I’m not just in Texas, but I would argue across the country because he’s sort of creating a new playbook for what governors can should, or maybe should not do.

[00:04:35] Alisha: In terms of their own members. And the final thing that I will say is I believe very strongly again, that parents should have options. And so I appreciate the energy and the focus and the sense of urgency to get people elected who support this too. But I just don’t know if this is the right way to do it.

[00:04:51] Albert: Yeah. We’re in this brave new world of politics. The Bully pulpit is a thing and new playbook, [00:05:00] new strategy. So, we’re all recording this before we know the results. So, I’m anxious to see what, will happen.

[00:05:05] Alisha: Same here.

[00:05:06] Albert: We’ll see. I got another story and well, you know, sorry, everything’s politicized these days, but hopefully I can talk about this without politicizing it. Cause you know, here’s the topic. It’s early childhood education in particular. Headstart.

[00:05:18] Albert: So there’s an article out this week from Politico talking about the president’s plan to increase pay for our early childhood educators. I mean, this has been a challenge particularly in early childhood education, Headstart in particular to get teachers to Stay and be in the positions, you know, to reduce turnover and the staff.

[00:05:40] Albert: And so, talking about policy levers it looks like the, the Biden administration is looking to increase salaries by about 10,000 actually on average. And actually, as part of the plan, there’s also some pay increases. It looks like for aides, janitors, and, other folks. So, you know, so they’re making that push, I think to try to address this [00:06:00] problem of teacher turnover and, and staff longevity or, or lack of it but sucks cause there’s always these trade-offs and so, you know, what this article talks about too, is that actually in order to identify the funds, to raise compensation The plan’s also going to have to cut back on the number of available seats in Headstarts as well.

[00:06:21] Albert: So, as I was reading this, I’m like, well, I guess it’s tough to escape the, the real trade offs that we often make. And I guess this is the tough thing that policymakers have to face. You know, how do you weigh these trade-offs? Now on the other hand, the article does mention that enrollment in Headstart has been declining.

[00:06:37] Albert: And so, so maybe having fewer slots is actually you know, meeting the demand that’s actually out there to put it one way, but we’ll see how this all shakes out. Yeah, there’s always this, tension between wanting to pay your teachers more to, attract the best candidates. but then also being in the black for the budget. You know, not going red in other aspects. And so, yeah, I know [00:07:00] I faced this being on the board of a little private school here in town. trying to weigh these trade offs, but not an easy task to do, but we’ll see how this all shakes out.

[00:07:08] Alisha: Yeah, it is tough. And I would like to believe that it’s a false choice because We all know that the federal government has lots and lots of money. The question is where we’re spending it. But I do think a really important priority. You know, Headstart is a federal program that’s been around for a very long time, and we need programs like that to make sure kids are ready.

[00:07:29] Alisha: You know, when they get to their kindergarten or K through 12 experience. So it is tough, but I understand if you want to at least get more attractive candidates, if you will, right, because some of these folks are being paid pennies and it’s kind of sad the very difficult job that they have to do.

[00:07:45] Alisha: So hopefully they will find some funds, but I think you raised a good point about the enrollment being down. So hopefully that means they can have. less slots because they don’t need them while they also are funding the teachers at the appropriate level. So thank you for that [00:08:00] story. Well, coming up Professor Cheng we have with us, Dr. Adrian Mims senior, who’s the founder and CEO of the calculus project. We’ll be right back.

[00:08:30] Albert: Dr. Adrian Mims Sr. is the founder and CEO of The Calculus Project. Its goal is to increase the number of Black, Hispanic, and low-income students enrolled in Calculus Honors and AP Calculus for STEM careers. The Calculus Project is impacting over 7, 000 students in over 100 Middle and high schools in Massachusetts and Florida.

[00:08:53] Albert: And it has won awards from the college board, Amtrak, the Boston Celtics and the Gates Foundation. [00:09:00] MIMS earned a bachelor’s in science and mathematics from the University of South Carolina, a master’s in teaching mathematics from Simmons College, a second master’s in educational leadership from Simmons College, and a doctorate in educational leadership from Boston College, Dr. MIMS. It’s a pleasure to have you on the show. Welcome.

[00:09:18] Adrian: Pleasure to be here. Thanks for having me.

[00:09:21] Albert: You’re the founder and CEO of the calculus project which seeks to increase minority and low-income students’ access to high-quality math as well as STEM careers Why don’t you begin by sharing with our listeners your own background?

[00:09:34] Albert: You, like me are a math major. So, you know, talk a little bit about that background the origin story of The Calculus Project.

[00:09:41] Adrian: I have to go all the way back to Spartanburg, South Carolina, because as I, embarked on this journey, a lot of things became very apparent to me.

[00:09:53] Adrian: And that’s why I’m so passionate about the work I do with the calculus project. But I graduated from James F. Burns High [00:10:00] School. For those people who are not familiar with the James F. Burns High School is in Spartanburg County and it did not integrate until 1969. So somehow, you know, they missed the memo about Brown versus the Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

[00:10:20] Adrian: They were in no hurry to integrate. I graduated in 1989. And even though I graduated from that 20 years later. It was still a racially hostile and it’s sometimes violent environment. And I went through school in one track, which was called college prep at another track, which was vocational students would go to.

[00:10:45] Adrian: Go to the high school for half the day and the rest of the day, they go to Artie Anderson and study fleet mechanics or construction or whatever. And then there was another track that just graduated from high school and they ended up either going into the military [00:11:00] or working in the mills. so, reflected, I found my old report card and I looked at my grades and I noticed when I took algebra to my grades were as follows. First quarter B, second quarter B took the mid-year F. Third quarter B, fourth quarter B took the final, got an F and my final grade was a C. Now, no one ever said anything to me about how is it that this, kid is failing the mid-year and the final, but he’s getting B’s through, the first and fourth quarters.

[00:11:34] Adrian: And I didn’t find out until later why that was happening. I go off to University of South Carolina. I decided to major in electrical engineering. I ended up changing my major, my junior year at a mathematics, which was tough. Because I had to take a lot of 500-level math courses together that they tell you never take at the same time.

[00:11:55] Adrian: Additionally, I’m first generation to go to college and I was working two [00:12:00] jobs to help. pay my way through college. So I had that additional burden. And so, I was scared because I realized my sophomore year I didn’t know how to study. And so when I reflected back on what was happening in high school, their lives, the evidence.

[00:12:16] Adrian: So, I got lucky. I ran into a young man from Togo who was there with his wife and children pursuing his doctorate in mathematics. His name is Christopher Demba. He saw a young man in the student lounge, struggling, trying to figure everything out with all those budget-level math books. And he came over and he said, can I help you?

[00:12:35] Adrian: And so he became my tutor. So I have my degree in mathematics from the University of South Carolina, but I got tutored and I got help. And so I credited him, Kofi Fadimba, for the calculus project. I moved to Boston. I started working at Brookline High School as a Metco tutor. For those people who may not be familiar with METCO, METCO is a voluntary [00:13:00] busing program that started here in Massachusetts in the late 1960s that bused students from Boston to wealthy suburban districts with the idea that if those students are attending schools in those districts, they will inherently benefit from those resources and do well in school.

[00:13:19] Adrian: I had just my degree in mathematics, no education courses. So I got an apprenticeship voucher for the students in math and physics. And while I was there at Brookline for 19 years, I became a full-time math teacher, associate dean, summer school director, and dean of students and went to graduate school a lot and got my doctorate from BC and my dissertation title is Improving African American achievement in geometry honors from those findings came the calculus project.

[00:13:49] Albert: Amazing. Speaking of The Calculus Project, there’s another project out there. The Algebra Project, this is founded by the late civil rights leader and educator, Bob Moses. So this is a national program aimed also at helping low-income students of color achieve math skills that you need for college math.

[00:14:06] Albert: Yeah, talk about his work in math education and, did he have an influence on you as you spearheaded calculus project?

[00:14:13] Adrian: Absolutely. I mean, I think pursuing my doctorate In education at BC was one of the best things that ever happened to me because prior to that, I never heard of the algebra project.

[00:14:25] Adrian: So, anyone who’s ever, written a dissertation, you have to do a lit review, a lot of reading and I learned about the algebra project and so without a doubt, he influenced me. I feel like the work I’m doing, I’m standing on his shoulders. He’s much bigger than I am in terms of his scope and what he did.

[00:14:47] Adrian: He was a visionary. He said back in the late, you know, the 1960s that algebra in the eighth grade was important and One of the quotes I remember from his book, Radical [00:15:00] Equations, still rings true today. He said, Today I want to argue the most urgent issue affecting poor people and people of color is economic access.

[00:15:09] Adrian: In today’s world, economic access and full citizenship depend crucially on math and science literacy, and it’s still true today. so, I feel fortunate. I wanted one of my biggest regrets. I met him a couple of times. I wish I had spent more time picking his brain, talking to him. I’m really good friends with two of his children, Omo and Maisha Moses.

[00:15:32] Adrian: That is one of my regrets that I didn’t take advantage of those opportunities.

[00:15:37] Albert: Well, let’s talk about another a little bit more well known know, high school math teacher, Jaime Escalante. So in the eighties, he was made famous in that movie stand and deliver about his work in Los Angeles public high schools.

[00:15:50] Albert: And assuming listeners know this movie, but I don’t know, maybe I’m mistaken, right? He produced remarkable AP calculus results with his students. Yeah, it could you talk about if he was [00:16:00] a influence on you? Are there lessons from his career? That you picked up on there’s these tensions there between high quality and academic math instruction and, and generally lower expectations we find in a lot of public education.

[00:16:14] Adrian: Oh, without a doubt. I mean, when you look at the calculus project, there are five. components. And when I say that it’s research supported, that research came from watching what other people did that was successful. So Stand and Deliver interesting enough, is one of the movies that we show students in the calculus part of our pride curriculum.

[00:16:37] Adrian: What Jaime Escalante did is what I wish more math educators would do. That is walk into some of the. Toughest situations and look at the students and say, I believe in you. And if you fail it’s because I failed you and I’m going to give you a hundred percent, give you everything that the kids who are [00:17:00] performing above the achievement gap have, I’m going to give you everything.

[00:17:04] Adrian: I’m going to make sure that I have high expectations and give you the support. And so that’s one of the reasons why, you know, he’s one of my heroes as well. If you look at what he did, he focused on good instruction, delivering additional time on tasks for students to learn the material. He had a belief in the students that helped them believe in themselves. And in the movie, he talked about Ghana, which means the desire to make sure that the students had that heat really focused on the community. If you get that movie, he built a community with those students. That’s very important. The sense of belonging basically developed a culture of math and collaboration and showed how the math was relevant, coupled with high expectations.

[00:17:50] Adrian: And there’s one particular scene in the movie. I don’t know if you remember this. He’s in the car with this guy who wants to quit school and become a mechanic and [00:18:00] Jaime almost crashes the car because he tells him to take a turn at the last minute, but he says something that’s very interesting to the young man in the passenger seat, he says all you see is the turn and not the road ahead. And so that’s poignant because in terms of students making decisions now and parents. Helping their children make these decisions. They’re trusting educators to give them the best advice. But in too many cases, they don’t necessarily see the road ahead of some of the unintended consequences of some of the choices that they’re making at the encouragement of some educators.

[00:18:38] Albert: Yeah. Well, you know, you’re, just talking about having high expectations for our, students and, keeping rigor in the curriculum. And so, being in Massachusetts in the nineties, Massachusetts was the leader for it. And setting up, high academic standards particularly in math.

[00:18:55] Albert: And so, all this was happening while the math wars were kind of raging across [00:19:00] American public education. So, could you just talk about the 2 sides of the math wars and how that informed your work and how it related to your work.

[00:19:08] Albert: And then also just with respect to the math standards in Massachusetts. Yeah. How did that relate to your work? And, perhaps became a benefit and added value, to what you’re trying to do.

[00:19:17] Adrian: There’s so many math wars that are going on right now. Yeah. It’s almost like picking your battle.

[00:19:24] Adrian: I think what’s interesting you know, when you think about education, when I think about education, you know, you got to think about, back in 1837, you know, with Horace Mann, you know, he was the secretary of education. Massachusetts really outperforms all of the rest of the states.

[00:19:41] Adrian: And I think it’s because there’s a culture here with expectations and education. You know, when you think about it. Massachusetts, you know, we’re like one of the most educated states. When you look at the percentage of people who have a bachelor’s, I think it’s close to 44 percent nationally.

[00:19:57] Adrian: It’s like 38 percent and then even [00:20:00] with professional degrees and in their colleges all over the place. And so what that leads to is high median household incomes. So it’s just. It’s a culture that continues to flourish and there’s an expectation that school officials, school committee members, superintendents, principals, and teachers are going to be held to a high standard by citizens.

[00:20:26] Adrian: So that drives a lot of it, I believe personally was interesting enough though, when I said earlier about, you know, how median household incomes. There was also an article in the Boston Globe that said the median net worth of someone who identified as black or African American in Boston is 8.

[00:20:44] Adrian: So on one hand, Massachusetts is amazing and doing exceptionally well, but it’s not working well for everyone. Unfortunately, and, you know, with regards to the standards when you look at the math [00:21:00] frameworks and common core standards, they’re really setting a trajectory for students to take algebra in the ninth grade, not necessarily the eighth grade, but a lot of the districts don’t pay attention to that.

[00:21:12] Adrian: They, you know, you got some students taking out as early as seventh grade. Yeah. Everybody is staying, I guess, within the framework for the most part, but not really sticking to it with fidelity and every place is doing their own thing.

[00:21:26] Alisha: I’m so glad you mentioned that. First of all, it’s great to have you.

[00:21:30] Alisha: Your story is quite inspiring and to be honest, as someone who’s not a math person this is quite fascinating to learn from you. So thanks for what you do. you talked about this algebra one piece. Um, In 2008, the prestigious U. S. National Mathematics Advisory Panel reviewed more than 16, 000 research publications and policies on this very topic.

[00:21:52] Alisha: And so can you talk more about Algebra One as this gateway course to all higher-level math? And why, [00:22:00] even after this advisory panel came out with this research, that we’re still continuing to struggle in America with teaching Algebra one in the eighth grade. What is this about?

[00:22:11] Adrian: Wow, that’s a long answer.

[00:22:14] Adrian: And I try to make it as succinct as possible because there’s so many. factors that contribute to this. I think the first thing is that you know, math is very comprehensive. You’re not going to be successful in algebra if you’re not proficient in arithmetic. And then when you follow the sequence of courses.

[00:22:36] Adrian: from pre-algebra, the algebra to geometry, the algebra to intrigue, the pre-calculus, it’s all comprehensive and you need all of that previous knowledge to be able to thrive and be successful in a calculus course. And there are a lot of data and research around the whole idea of course taking patterns and what that means [00:23:00] for students during high school and then post-secondary.

[00:23:03] Adrian: One of the challenges though and you know, this is going to sound political, but there is no national curriculum for math and curricula in general, English, social studies, science There is no national curriculum. And when you just look solely at Massachusetts I was on for the state a mathematics pathway task force, and I learned a lot from my participation on that task force.

[00:23:30] Adrian: One of the things I learned is that just for 8th grade alone. They are about 33 different math courses offered in the eighth grade, just in the eighth grade, 33 different courses. And just because a school says that they’re teaching algebra doesn’t mean that they’re teaching algebra.

[00:23:48] Adrian: So that really makes our jobs very challenging at the calculus project, because when we work with districts, they’ll say, okay, well, we’re teaching these particular courses. And I say, okay, that’s [00:24:00] really sweet. That’s nice. Let me see the syllabi because what’s happening in some cases, there are students who are being remediated and no one knows it except the teachers.

[00:24:12] Adrian: The students don’t know what the parents don’t know it. Because when you look at what the course is called and you look at what they’re being taught. It is not college preparatory material. Another thing I just want to say is that with regard to why algebra is really tough, schools struggle with vertical alignment with their curriculum.

[00:24:33] Adrian: And what I mean when I say that is, what should be taught, how it should be taught and how much time you spend teaching it. And too often teachers. They’re spending a lot of time on the wrong content, and so you just can’t go into a school district and say, hey, algebra for all eighth graders without looking at what is being taught from kindergarten all the way up to eighth grade, and [00:25:00] even some of the districts that identifies the best school districts really struggle with figuring out what needs to be taught, how it needs to be taught and for what period of time.

[00:25:09] Alisha: Very interesting and helpful. You mentioned that we don’t have a national math curriculum. We do, or at least we attempted to have. Math standards, right? So a decade ago D. C. Based educational trade groups, the federal government, and major foundations. I was in the legislature at that time, so I’ll include policymakers.

[00:25:34] Alisha: We’re all pushing common core math national standards, which ultimately most states adopted. And I’ve been wanting to ask someone this question for a long time. So can you talk about your thoughts on Common Core Math and why, since 2010, we still have not been successful in delivering positive math results for American students?

[00:25:59] Alisha: What happened?

[00:26:00] Adrian: Well, I think somewhat answered the question a little bit when you said most states adopted it. Not all states adopted it. that’s one challenge. But I mean, when you think about it. Ed reform that comes from the top down, meaning from the federal government down to the actual towns and school districts.

[00:26:20] Adrian: We’ve never been successful at education reform, whether it’s no child left behind or the common core standards. What happens is, that what we’re saying from the federal level is really taking a cookie-cutter approach. But you can’t take a cookie-cutter approach when it comes to education reform, because what happens in districts is really controlled locally by the school committees and the school boards.

[00:26:48] Adrian: And because we have an actual framework, it gives a lot of latitude, so you can operate within the confines of the framework, but that creates a lot of variability [00:27:00] there. I think the other challenge too, is some areas of this country do a better job recruiting and retaining. Teachers in particular, math and science teachers, in other areas struggle significantly because they don’t pay very well.

[00:27:17] Adrian: If you’re a math or science teacher, you can go into the private sector in some areas of the country and make two or three times that amount. And since the pandemic, these jobs in the private sector are even more attractive because you can work at home for three days and go in the office for two days.

[00:27:32] Adrian: And so going into the teacher profession, one of the biggest attractions was the fact that you have your summers off people are working from home, which is almost just as comfortable for them. So, state level down to the actual towns, you have just a lot of. Disparity in terms of how they’re teaching math.

[00:27:56] Adrian: And I think that goes back to what I said earlier. The fact that you [00:28:00] have 33 different math classes for the 8th grade. deviating a lot from, I guess, the spirit of what people thought would result from coming core math.

[00:28:12] Alisha: Yeah, understood. And I think it just speaks to. Many of the challenges that we have in our public education system, right?

[00:28:20] Alisha: So no matter what the content area is, if you don’t have highly effective teachers who are well trained, you know, people are aligned, all of that, you kind of end up with the same results regardless of the content area. So we appreciate that. I want to continue to talk about math scores and where we are in the recent U.S. NAEP scores it was revealed that two decades of already modest progress are nearly gone as national math results hit historic lows. And that’s even in the decade before COVID. where two-thirds of the states experienced declines in math, which were greatly worsened, we know, by the pandemic. And [00:29:00] so, imagine you are talking to educators and policymakers and other folks within education.

[00:29:07] Alisha: How do you think we can address this chronic math underperformance, these wide achievement gaps, and the pandemic learning loss?

[00:29:17] Adrian: When it comes to math, what I would do I would take a multi-pronged approach. And the first thing that I would do is, when you look at kindergarten, first grade, second grade, as soon as students enter the schoolhouse, there are already gaps, but the thing is, is that, when you look at first, second and third graders, the gaps aren’t as great, but when you follow a particular class all the way up to their senior year in high school, those gaps widen.

[00:29:48] Adrian: So one of the things that I would do, I would make a significant investment in resources in K to three actually elementary all the way up [00:30:00] to 12th grade. The interesting thing is, is that if you start early With interventions, and when I say interventions, 1 is I mentioned before about the vertical alignment.

[00:30:10] Adrian: That’s important. But also, if you’re assessing students, and you see that they’re already behind, then create opportunities for them to have more time to learn the content, either extend the school day. or create learning opportunities during the summer to mitigate summer learning loss. There has to be some time built in for students to get ahead.

[00:30:33] Adrian: And so that takes a significant investment in time and resources. I mean, we’re dealing with a school system right now where there are teachers who are buying their own supplies for the classroom. I think that’s utterly ridiculous. Absolutely. We have to get very serious about education. I call it the quiet crisis because don’t necessarily see it on TV. You know, the number of teachers who will leave the profession never to return. you never [00:31:00] understand that some of the students, the teachers that they have before them are permanent subs who don’t necessarily know the content. So that is a huge piece too.

[00:31:10] Adrian: We have to build in those supports and for Those students who are in middle school and in high school, we have to have those same interventions as well. And I would even add that we need to make sure that we’re incorporating and making it mandatory that students understand financial literacy.

[00:31:26] Adrian: We can make it an elective or we could integrate it into the math courses, but no student should graduate from high school without some basic fundamental knowledge about financial literacy.

[00:31:40] Alisha: Yes, and amen. I’m so glad you said that. So my final question for many decades has been international comparisons in K 12.

[00:31:51] Alisha: So you’ve got the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, also known as TIMSS, and the Program for International Student Assessment. Pizza. [00:32:00] Can you compare the level of academic preparation in math that high-performing international students experience to that of American students? And what are some of the countries you think are most effective at teaching math at the K-12 level?

[00:32:14] Adrian: Yeah, I mean, immediately think about Finland. I mean, here’s what we have to do in the United States. We have to treat teaching as if it’s a profession. And unfortunately, that doesn’t happen. When you think about becoming a teacher in the United States, there are so many pathways to becoming a teacher.

[00:32:36] Adrian: And just to give you an example, and this is just an example, you can have a bachelor’s and you can be a landscaper with a bachelor’s degree. And literally within two years, You could be in a classroom teaching, or you could be running a school. And when you think about other whether you’re going to be an airline pilot or [00:33:00] whether you’re going to become a cardiologist.

[00:33:01] Adrian: There’s only one way you’re going to fly for Delta United or Spirit Airlines. There’s only one way you’re going to become a physician. And what we have to do, we have to make sure that the graduate schools of education are doing an adequate job preparing teachers for what they’re going to see when they really get out there into these schools and in the classrooms.

[00:33:24] Adrian: I’ll give you an example. We have urban education and then we have regular education. why aren’t teachers or. future educators also learn about urban education as well as mainstream education courses. I never really understood that because now we have a situation where some districts that were once kind of like urban-suburban, they’re becoming urban suburban uh, schools.

[00:33:52] Adrian: And so What other countries do, they do a good job at training teachers, paying teachers well, and [00:34:00] retaining teachers. We really struggle with really good induction programs. It’s hard for us to retain teachers. One last thing, I just like to add that there’s a huge push to add more diversity to the teaching profession.

[00:34:15] Adrian: And in some cases, and I’ve had several conversations with. Brand new teachers of color. They don’t end up staying in the profession very long because what happens as soon as they get into a particular school they put them with some of the most challenging kids. And in a lot of cases, they’re challenging kids of color and they don’t provide them with the support that they need leadership really matters and the average career superintendent in the school district is about three years there’s high turnover there. So a structural problem. We have to build in the support and make sure that teachers have everything that they need.

[00:34:57] Alisha: Absolutely. Again, I want to thank you, [00:35:00] Dr Mims. Your work is so impactful and I think the things that you’ve shared today As I said before, it can solve a lot of problems in education, right? Leadership, effective teaching, the right induction programs. How do we retain great teachers? All of those things are the challenges that many schools are facing.

[00:35:18] Alisha: And so I think if people listen, we heard some really good practical advice today. So thank you, thank you, thank you for all that you’re doing and being with us on The Learning Curve.

[00:35:27] Adrian: Thank you so much. I really enjoyed it. Have a great day.

[00:35:53] Alisha: Thank you, Dr. Mims, for joining us. That was quite fascinating, Professor, wasn’t it?

[00:35:58] Albert: Oh, yeah. Love hearing about this work. Really important and, Certainly always love talking about math.

[00:36:02] Alisha: Yes, you do. I love it. So before we go we definitely want to do the tweet of the week.

[00:36:09] Alisha: And this one. Is from NASA and it’s celebrating Women’s History Month. Yay for Women’s History Month celebrating women astronauts in 2024. And so what was very cool is that in this article, it talks about that as of February 29th of this year, 75 women have flown in space of these women, 47 have worked on the International Space Station.

[00:36:34] Alisha: As long duration expedition, crew members, visitors on space, the list goes on. So very, very cool. I love this as a way to celebrate women. We think about all kinds of careers that women are in. We don’t talk enough about aerospace. So this was very, very cool. So make sure you check out that article.

[00:36:54] Alisha: Albert, it has been wonderful as always to co-host with you. Thanks for joining this week.

[00:37:00] Albert: You’re very welcome. Always a pleasure to co-host with you as well.

[00:37:03] Alisha: Absolutely. And I want our listeners to join us next week. We will have Professor Joan Hedrick. She is the Charles A Dana professor of history emeritus at Trinity College and a Pulitzer prize-winning author of Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Life.

[00:37:20] Alisha: See you next week.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts University of Arkansas Prof. Albert Cheng and Alisha Searcy interview Dr. Adrian Mims, founder of The Calculus Project. He delves into his mission to enhance math education for minority and low-income students, drawing inspiration from Bob Moses’s Algebra Project and Jaime Escalante’s teaching legacy. Dr. Mims navigates through the contentious “math wars” and underscores the pivotal role of Algebra I as a gateway to higher math. He also evaluates the negative impact of Common Core math standards, and proposes strategies to combat pandemic-induced learning setbacks and bridge the gap in math proficiency between American students and their international counterparts.

Stories of the Week: Albert spoke on an article from Politico about the Biden administration’s new plan for the Head Start program; Alisha discussed an article from National Review on school choice in Texas.

Guest:

Dr. Adrian Mims, Sr. is the founder & CEO of The Calculus Project. Its goal is to increase the number of black, Hispanic, and low-income students enrolled in Calculus Honors and AP Calculus for STEM careers. The Calculus Project is impacting over 7,000 students in over 100 middle and high schools in Massachusetts and Florida; and its won awards from the College Board, Amtrak, the Boston Celtics, and the Gates Foundation. Mims earned a B.S. in Mathematics from the University of South Carolina, an M.A. in Teaching Mathematics from Simmons College, a second masters in Educational Leadership from Simmons College, and a Doctorate in Educational Leadership from Boston College.

Dr. Adrian Mims, Sr. is the founder & CEO of The Calculus Project. Its goal is to increase the number of black, Hispanic, and low-income students enrolled in Calculus Honors and AP Calculus for STEM careers. The Calculus Project is impacting over 7,000 students in over 100 middle and high schools in Massachusetts and Florida; and its won awards from the College Board, Amtrak, the Boston Celtics, and the Gates Foundation. Mims earned a B.S. in Mathematics from the University of South Carolina, an M.A. in Teaching Mathematics from Simmons College, a second masters in Educational Leadership from Simmons College, and a Doctorate in Educational Leadership from Boston College.

Tweet of the Week: