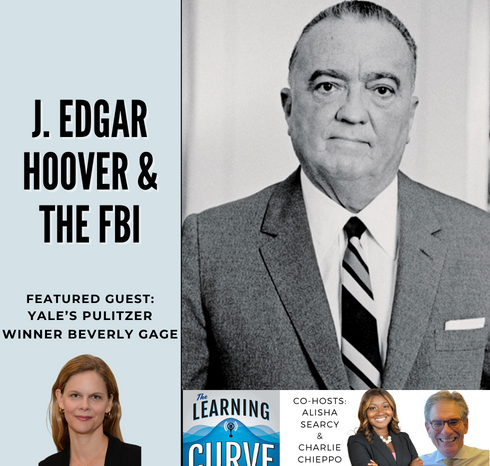

Yale University Pulitzer Winner Beverly Gage on J. Edgar Hoover & the FBI

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Podcast

Transcript with Professor Beverly Gage, author of G Man, J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century

[00:00:00] Alisha: Well, hello there and welcome back to The Learning Curve podcast. I am your cohost this week, Alisha Searcy, and I am joined by my friend, Charlie Chieppo. How are you, Charlie?

[00:00:34] Charlie: Well, I’m better now that I’m here with you, Alisha. Great to be co-hosting with you again.

[00:00:39] Alisha: Always love hanging out with you. Looking forward to our guests today, yes. But first, of course, we’ve got to get into the stories of the week. Would you like to go first?

[00:00:50] Charlie: Well, sure. My story for this week is me getting on a familiar hobby horse. I’m going to talk a little bit about actually a study that Pioneer just came out with called “MCAS, NAEP, and Educational Accountability.” So, MCAS is the Massachusetts state test that students have to pass in English, math, and science to graduate from high school. So, after enactment of a 1993 education reform law that, among other things, created MCAS, Massachusetts schools dramatically improved. They became the best performers in the country on NAEP, SAT scores went up, graduation rates went up, and we even were globally competitive on international assessments.

[00:01:33] Charlie: Those of you who are unfamiliar with education politics might be surprised to know that, of course, the response to that has been to tear it all down. The standards have been weakened. We had an independent school district accountability office that’s been eliminated. What were the nation’s best charter schools have been severely limited. So now we have a new measure that’s going to come before Massachusetts voters in November to get rid of the MCAS graduation requirement.

The thing that I have really become obsessed with of late is this idea that all of these changes are happening in education, many of them promoted in the name of equity. But over and over again what we see is that these changes too often harm both performance and equity. You know, to make the system more inequitable. So, you know, I don’t think it’s really a surprise given the changes that have happened here that even before the pandemic Massachusetts NAEP scores were plummeting.

[00:02:40] Charlie: But what’s interesting to me is that those declines have been worst among low-income students, among the students that they were designed to try to help. So, what this paper does is it really sort of shows that under the regime of high standards and tests that provide the data that’s needed to diagnose problems — for example, the gap in math performance on the MCAS test between low-income and statewide averages went from 23 points in 2006 down to eight points. Now we’re moving in exactly the wrong direction. So, I guess I would say that in my view, anyway, the facts are clear that educational quality and equity go hand in hand. I wonder whether the facts matter. We’ll find out coming in November.

[00:03:31] Alisha: Right. You know, it’s funny you mentioned this, Charlie. We have a similar movement happening in Georgia with different players. And I don’t want to make this conversation political, but I will say that whereas you have Massachusetts and teachers unions, and I’m guessing more Democratic-leaning folks. And when you say, you know, this is about equity, I’m guessing that’s who the messengers are on this. In our state, which is Republican controlled, those are the folks our leaders in the state are the ones really those interesting. They’re the ones who are pushing this, and it’s not about equity.

[00:04:06] Alisha: I can’t even say there is a message around it, but our state accountability system — where you could get a score and know how each school and each system is doing — you can’t get that cumulative score any longer. They drastically changed what it means to read proficiently in third grade. And so now the cut score is much lower. And so, these are the kinds of things that — I don’t understand the lack of accountability and how that helps students and how it helps parents have information that they need to know how their students are doing, how we can help teachers if they’re high performers or if they’re not, you know, how we give them information that they need.

[00:04:47] Alisha: And so, I don’t understand this move in this direction. And so, whether you’re a Democrat or a Republican or where you fall on the political spectrum, I think we all want to have good information so that we can understand where our kids are, right? You know, when you go to the doctor, you take tests and the doctor tells you how you’re doing based on those tests.

[00:05:07] Alisha: And so, we, I don’t know where we’re heading with this, but it’s not the right direction in my opinion. I’m hoping that let’s say cooler heads prevail. Change in mindset again, regardless of political party. But I need to know where these kids are and how we can increase their performance.

[00:05:25] Charlie: Well, as we know, you know, the pendulum always does swing back. It’s a matter of when.

[00:05:30] Alisha: Yes. And I hope it’s very soon. So, thank you, Charlie. That’s a good story. Mine for the week comes from a friend of mine, actually, Curtis Valentine, who wrote a piece for Real Clear Education entitled, “Are HBCUs the Key to the Future?” And in this piece, he’s talking about the role of HBCUs in terms of starting charter schools. So, we know that when you look at NAEP scores, as an example, white students outperform black students in reading and math in traditional public schools. But when you look at charter schools, black charter students gain an equivalent of 35 additional days of learning and reading and 29 additional days in math compared to their counterparts in traditional public schools. So clearly something is afoot. Something is going well when these students are in charter school, and we could have a long conversation about what those things might be.

[00:06:31] Alisha: But in this article, he’s pointing out that historically black colleges and universities could actually be an answer to one of these challenges. by allowing them to authorize charter schools. I live in Atlanta. I attended Spelman College, which by the way, happens to be the number one HBCU, according to U.S. News & World Report.

[00:06:53] Alisha:. And we just happened to get a hundred million dollar grant a few weeks ago to make sure that we continue to have our Spelman students have scholarships so that they can, finish their education. And so, we know, of course, that the purpose of historically black colleges and universities initially, right, were because black students couldn’t go to majority white colleges and universities. And so these institutions were started to ensure that we too could get an education. And so, when you compare the work of HBCUs, which have now been around for a very long time, hundreds of years, we’re talking to the work that is happening in charter schools and the impact that they’re having on black and brown students, I think there’s a strong connection here. And so, Curtis is making the point that HBCUs should, in fact, be in the business of authorizing and starting charter schools. So, some people might say that’s controversial. I actually like the idea. I think about again, the history of HBCUs and how they know to nurture and challenge and support black and brown students.

[00:08:01] Alisha: And so, I like the start of this conversation. I’m hoping that as many organizations are starting these conversations — and I’m hearing about it nationally — that we actually see some of these pilots happening and see the work that can happen. Because as we know, Charlie, part of the whole purpose of charter schools is to be innovative, to try new things, to do things differently, and I think this is a great start to that.

[00:08:26] Charlie: Yeah, I think that’s a great idea. So, question that comes to my mind, who currently approves charter schools in Georgia?

[00:08:33] Alisha: So, we have local school districts, and I’m sad to say that I’m guessing in the last eight years — we have 180 school districts — there have probably been five charter schools authorized in the last eight to 10 years.

[00:08:50] Charlie: Well, that’s five more than you’d have if school districts were making decisions in Massachusetts!

[00:08:56] Alisha: So, it’s terrible. And then because of that, and I actually am one of the co-sponsors, we have the state Charter Schools Commission, which is a state, authorizer but all the schools are solely funded by state funding, so that’s not necessarily a most sustainable policy idea, right? And so those are the two and it would be interesting to have HBCUs here in Georgia because we have many of them serve as an authorizer.

[00:09:23] Charlie: Yeah, that’s worth watching. That’s interesting.

[00:09:25] Alisha: Yeah, it really is. So yes, more to come on that. It should be very interesting to watch. I am looking forward to our show today. We have Professor Beverly Gage, who is the John Lewis Gaddis Professor of History at Yale University. And we’re going to talk about her book, G Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century. So, stay tuned.[00:10:00]

[00:10:05] Charlie: Beverly Gage is the John Lewis Gaddis Professor of History at Yale University. Her book, G Man, J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, received the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Biography, Bancroft Prize in American History, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Biography, the Barbara and David Zelaznik Book Prize in American History, and the L.S.W. Hawley Prize of the Organization of American Historians. G Man was named a Best Book of 2022 by the Washington Post, The Atlantic, Publishers Weekly, the New Yorker, the New York Times, and Smithsonian. In 2009, Professor Gage received the Sarai Ribicoff Award for Teaching Excellence in Yale College.

[00:10:50] Charlie: She’s graduated Yale University with a BA Magna Cum Laude in American Studies, and she earned a PhD in History from Columbia University. Welcome, Professor, Gage.

Beverly: Thank you.

Charlie: You won the Pulitzer Prize, congratulations, for your definitive biography G Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century. Would you share what drew you to Hoover as a subject as well as briefly summarize why he was among the 20th century’s most influential public officials?

[00:11:19] Beverly: I was drawn to Hoover as a subject precisely for the reason that you say, that he was an enormously influential public official, head of the FBI from 1924 to 1972, during which time he had his fingers in nearly everything in American politics. And I thought that our popular depictions of him, especially, had become a little bit one dimensional.

[00:11:47] Beverly: We usually think of him as this kind of horrible villain, which in many ways he was. But I thought that his influence was too important to simply leave like that. And also, I was drawn to being able to, through this one figure, tell a big story about American politics and government in the 20th century.

[00:12:09] Charlie: Right. Well, you know, I think that one of the ways that shows just how influential he was is that to this day, I remember sitting in home room at the end of the day in eighth grade and the announcement coming over that he had died. It’s funny, I think people who are younger probably don’t really understand exactly just what a large place he had in the lives of people of a certain age. So, going back, Hoover was born in 1895 in Washington, D.C. He’s the son of a career federal civil servant. Could you talk about Hoover’s early life, his family, formative educational fraternity experiences, his intellectual interests, and how his D.C. upbringing shaped his outlook in his career?

[00:12:53] Beverly: The fact of D.C., which is where he’s born and is also where he dies — Hoover never lives anywhere else — is one of the great facts of his life. He is a creature of Washington D.C., and this book really is about Washington, D.C., both as the center of federal government, which expands so dramatically in the 20th century, but also as a living city, a place where all sorts of people lived. So, Hoover was born there in 1895, as you say. It’s not a moment in which Washington is a particularly big or influential city, but I think it’s really important for his story in two ways. One, he is born into a Washington that is a city already of federal service, but in particular, that is a city where nobody can vote. Until, you know, the late 20th century, Washington residents basically had no say either over their own government or the national government. And so, Hoover grew up in a world of government service, of career government service, that was a little bit different from the world of politics. He never voted, he never joined a political party, but he was imbued with this history and tradition of government service from a very young age. And then, the second piece that’s really important about Washington was that it was a city that was actively undergoing formal segregation, racial segregation during the years of his childhood and young adulthood. And so, many of his early experiences from going to the segregated Washington public school system to entering federal service at the moment that federal employment is being much more rigidly segregated — all of that really shapes his racial outlook and his conservative outlook.

[00:14:45] Beverly: One institution that really fascinated me that I hadn’t known much about before writing this biography was his college fraternity at George Washington University, which was a fraternity called Kappa Alpha, that was an explicitly white, Southern, segregationist fraternity really imbued in all of these ideas about The Lost Cause, about the righteousness of the Confederacy, and so he was really influenced by that as well.

[00:15:14] Charlie: Wow, interesting. So, early on, Hoover worked for President Woodrow Wilson’s Justice Department running the War Emergency Division’s Alien Enemy Bureau. After World War I, he led the Bureaus of Investigation’s General Intelligence Division, which monitored domestic radicals, including Marcus Garvey, labor activists, anarchists, Communists. Would you talk about young Hoover’s work as a Progressive-era federal official?

[00:15:39] Beverly: Hoover happened to graduate from law school in the spring of 1917, which was a pretty dramatic moment in Washington, D.C. The United States was just entering the First World War, and instead of going into military service, he went straight into the Justice Department. The Justice Department was itself really being transformed by the war. It had all sorts of new duties in surveillance and draft enforcement, and there were all sorts of new speech restrictions and alien enemy provisions. All of this was just really being invented. And so, Hoover was sort of there on the ground floor. He was not the head of the alien enemy division, but he got his first start as a very young lawyer working in German registration and internment, which is something we don’t think a whole lot about. About 10,000 Germans were interned in the United States during the First World War. And Hoover was in charge of that very early on, or at least one of the people participating in it.

[00:16:44] Beverly: And then he was so good at it that when the war came to an end, and they were looking around for someone to kind of create and run a new division within the Justice Department that would keep tabs mostly on left wing radicals, civil rights activists, that sort of person, in times of peace, they turned to Hoover. And he became an early architect of that kind of surveillance, and especially of the Palmer raids, which were some deportation raids aimed at anarchists and Communists during those years.

[00:17:17] Charlie: So, as director of the Bureau of Investigation he used fighting the high-profile bank robber, John Dillinger, to expand the BOI into the FBI in 1935. Could you talk about Hoover’s public showdowns with gangsters and his skill at attracting wider publicity to support his kind of crime fighting crusades?

[00:17:37] Beverly: Hoover became head of the FBI in 1924 when he was just 29 years old, but for that first decade that he was there he was not particularly well known and he was mostly interested it in internal reforms, things that would kind of clean up and professionalize the Bureau. And so it wasn’t until the 1930s, in the midst of the New Deal, that Hoover really began to become, as you said, public celebrity and also became the sort of crime fighter that we would recognize today. We tend to think of, you know, the WPA or the TVA or other institutions as our kind of New Deal alphabet agencies, but the FBI is another one of them. It got its name in 1935. And it’s a period when Hoover gets lots and lots of new power. His agents start carrying weapons, they get put in charge of interstate bank robbery and interstate kidnapping, two very big deals in the ‘30s.

[00:18:39] Beverly: And coming out of that, he becomes also kind of a master of public relations. And so, you see a whole wave of. films and comic books and press features touting J. Edgar Hoover as our new great American hero and specifically as a G man, sort of the G man par excellence government man. And that is the, that’s the title of my book.

[00:19:03] Charlie: Under FDR the FBI’s authority, competence, and preeminence in domestic intelligence all grew. For example, Hoover expanded the bureau’s fingerprint files in the Identification Division and created the FBI lab to examine and analyze evidence. Would you discuss Hoover’s FBI and its pioneering work in criminology?

[00:19:22] Beverly: A lot of what Hoover did during that first decade as director, so from 1924 up to kind of the mid- to late ‘30s, was to try to turn the FBI into a model for other law enforcement bodies in the country. So, most law enforcement and crime fighting in the United States then and now is done at a local level. And so, Hoover had this tiny little federal bureau. And he thought, you know, kind of what can I do with this that would actually be useful and important? And a lot of the answers that he came up with had to do with his [00:20:00] vision of creating a kind of white-collar professional college educated law enforcement elite that could come up with best practices, apply the most scientific standards to law enforcement and really give the profession of policing and law enforcement new respect. So, he went out of his way to get the FBI jurisdiction and ownership over a whole host of things where he thought the FBI could be useful. One, as you said, was the fingerprint division, really bringing together national fingerprints so that local police departments could check in with the Bureau and have all of that in one place.

[00:20:40] Beverly: Another one was crime statistics, really until the 1930s there was no central repository for crime statistics. No one was collecting national crime statistics. And there was a big debate over who should do it. And Hoover won that debate. He created the FBI lab, which was supposed to be this kind of elite scientific forensics force.

[00:21:03] Beverly: And then to disseminate a lot of this information down to local law enforcement. And I think also to create his own kind of power and influence. He created the FBI Academy, which was training center, not only for FBI agents, but specifically for local law enforcement officials and international law enforcement officials who could come and be trained at Quantico for eight weeks, 12 weeks, something like that, and then take their knowledge back. All of those things still exist. All of them are still being run through the Justice Department and the FBI.

[00:21:40] Alisha: Fascinating, Professor Gates. Thank you so much for being with us. We’re learning a lot today, that’s for sure. And my husband actually is in law enforcement, so I can’t wait to share some of these things with him. I want to ask you about Clyde Tolson, who was Hoover’s right-hand man, associate FBI director, and life partner. Could you talk about their professional and their private relationship?

[00:22:03] Beverly: Clyde Tolson’s personal and professional relationships with Hoover were very fused. He was the most important man in Hoover’s life and is really a fascinating character in the book to me for that reason. He started out really as one of Hoover’s model agents. He came into the Bureau in the 1920s and he had gone to George Washington University, just like Hoover. He had joined a fraternity, just like Hoover, though not the same fraternity that Hoover was in, and this was kind of a type that Hoover really liked during his early years. He wanted men like him, who shared his background and his values, and they were going to be this kind of tight-knit elite corps. But Tolson became very different and special pretty early on.

[00:22:54] Beverly: By the mid 1930s, he was Hoover’s number two man at the Bureau and really spent the rest of his career as the number two figure at the Bureau until the day that Hoover died. But more than that, they were effectively life partners. They traveled together. They went to dinner parties together. They entertained together. No, they went to Broadway shows and nightclubs and everything that you could possibly imagine kind of a social spouse doing. They did for each other and so one of the kind of things that I had to figure out as a biographer and one of the big questions of Hoover’s life is, you know, was this a sexual and romantic relationship?

[00:23:40] Beverly: And we have some evidence about that and then there are some limits to that evidence. Their relationship was, I think, to many of our minds, surprisingly public. All of those things I just listed off were very public. They traveled and were treated as a social couple. You know, when you invited Edgar to do something, you also were going to invite Clyde.

[00:24:02] Beverly: And so, there’s just lots of documentation of this public partnership that they had that was deeply personal. It’s a little harder to tell exactly how they felt about each other and whether or not they were in fact having sex, Hoover and Tolson clearly loved each other, they cared a lot about each other, they were very intimate with each other with a lot of, for instance, vacation photos of the two of them, you know, off the beach together, taking shirtless photos of each other.

[00:24:34] Beverly: But whether that became a sexual relationship or not, we just — we do know that neither one of them married, neither one of them really dated women, and neither one of them had any children.

[00:24:44] Charlie: The thing I was so about, sorry to interject, was there’s picture in your book of Tolson at Hoover’s wedding, and the look on his face, you talk about uh, picture tells a thousand words, the look, I’ve just never seen anyone look as bereft as he did in that picture. It was really, I thought it was remarkable.

[00:25:06] Beverly: Yeah, I think that’s actually the final image of the last chapter of the book is of Hoover’s funeral and of the military honor guard at that funeral, actually taking the flag from on Hoover’s coffin, folding it up and handing it very publicly to Tolson, as you would to a spouse or next of kin. And so, it was both this intensely private relationship and one that was very public and very widely recognized.

[00:25:38] Alisha: Very, very fascinating. Thank you for that. So, during the 1950s and across the Cold War, Hoover’s FBI turned its attention back to the war on Communism and rooting out Soviet spies, including aggressively prosecuting accused spies like Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs. Can you talk about Hoover in this role as a cold warrior?

THIS FAR about 26:00

[00:25:59] Beverly: This was really the cause of Hoover’s life, the thing that he cared the most about, and I think probably the place that he had the widest influence outside of kind of professional law enforcement. And some of the techniques that we talked about there, you know, from very early on Hoover was a devout anti-communist, and he really thought of himself as the government’s great expert on Communism. Within the Bureau in the 1940s, they used to talk about themselves as the quote one bulwark against the Communist threat in the United States. And I think what makes Hoover really interesting and powerful on this question is that, unlike a figure like Joseph McCarthy, right, who was a very headline-grabbing demagogue who was there in a very prominent way in the ‘50s, but kind of came and went — he burst on the national scene in 1950, he was censured by his own Senate colleagues by the end of 1954, and then he kind of drank himself to death and was gone, died in 1957. Right, so we tend to imagine someone like McCarthy, but Hoover was much more powerful and much more sustained, and I think really built a whole range of structures to kind of prosecute the Red Scare and the broader anti-communist agenda. And that was everything from what the FBI was doing in terms of surveillance and investigation and sometimes court cases to writing his own books and making his own speeches and declarations about the American way of life and how individual citizens could fight Communism.

[00:27:45] Beverly: He hooked up with lots of congressional committees in order to prosecute the fight against Communism, and so he has this whole menu of things that he’s up to. As you say, one of them was espionage investigations, which became part of the FBI’s area of expertise beginning in the Second World War. And there, a lot of those were very, very controversial at the time, especially the prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and their ultimate execution. A lot of the evidence that has come out since the end of the Cold War has tended to be somewhat more vindicating for Hoover than a lot of people thought at the time. The FBI was running some secret programs where they did have pretty good information about some of these espionage questions, but these were secret programs, and they weren’t made public at the time.

[00:28:40] Alisha: Speaking of surveillance, President Kennedy reportedly said you don’t fire “God,” when asked about removing Hoover as FBI director. Can you talk about JFK and LBJ’s dealings with Hoover, including the bureaucratic leverage he wielded over them and his illegal wiretapping of Dr. King and figures within the civil rights movement?

[00:29:04] Beverly: One of the great facts of Hoover’s career, and I think one of the things that’s most amazing to think about today, is not only that he was there for 48 years in that job, but that meant that he stayed on through eight different presidents. Four of them were Republicans. Four of them were Democrats. Nobody ever fired him, right? That included John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. We tend to think about Kennedy and Johnson as being pretty similar figures, but actually they had very different relationships with Hoover. Kennedy and Hoover were often really at odds in terms of their personal priorities, all sorts of things, especially the fact that Kennedy appointed his brother Robert as Attorney General, which meant that Robert was Hoover’s boss.

[00:29:54] Beverly: So, there’s lots of conflict during the Kennedy years with Hoover. Lyndon Johnson, on the other hand, really liked Hoover. And one of the first things Johnson did once he became president was to exempt Hoover from what was then the federal mandatory retirement age of 70. So, in some alternate world, J. Edgar Hoover would have been forced into retirement on January 1, 1965. And I think that the history of the ‘60s would have looked very different. But Johnson liked Hoover and he found him very useful so, wanted to keep him in office. The question of the FBI surveillance of the civil rights movement in general and of Martin Luther King in particular is one of the big, things that I address in the book.

[00:30:45] Beverly: And I think with King in particular, it’s a pretty complicated story. I mean, the FBI starts out in the late fifties and early sixties interested in King because there are several activists around him who had been involved in the Communist party. So, it’s sort of an extension of this Red Scare politics, but very quickly this escalates into sort of a real vendetta against King. They begin wiretapping King himself, his office, his home. They start following him around the country and planting bugs in his hotel rooms, recording his sex life. And then I think in the most notorious and really outrageous moment, in late 1964, they take those recordings, they send them to King along with a sort of anonymous letter purporting to be from a black admirer that says, you know, King, I used to think you were so great, but now you’re just this horrible kind of sexual beast.

[00:31:45] Beverly: It’s a really racist letter, lots of pretty abusive language. And it ends with them saying, you know what you have to do, which King interpreted as an effort by the FBI to get him to actually kill himself. So, it’s a really outrageous, often quite illegal campaign that they’re running. I think the thing about the Kennedys and about Johnson is they knew quite a lot about what was going on, and it’s not clear that they had many objections to it.

[00:32:16] Beverly: Of course, on the one hand, they’re championing civil rights. On the other hand, they’re pretty suspicious of King himself, are not always enthused about him, and particularly want, you know, mechanisms of control over King. So, Robert Kennedy actually signs the wiretap order for Martin Luther King. Lyndon Johnson loves getting the FBI’s reports on Martin Luther King. And in fact, at the 1964 Democratic Convention, he explicitly asks the FBI to spy on King and other civil rights activists and report back to him so that he can both know what’s going on and attempt to kind of contain it and control it. So, it’s a complicated story.

[00:32:59] Alisha: [00:33:00] Yeah. It sounds like a little bit of duality as well.

[00:33:01] Beverly: Absolutely. They’re kind of doing both things at once. Some are more public, some are more private. Some are more critical of Hoover, and then some are much more on the side of collaborating with him.

[00:33:15] Alisha: Wow. Very, very interesting. So, I want to move on to talk about the counterintelligence program, also known as COINTELPRO conducted between 1956 and ’71, which was perhaps Hoover’s most controversial covert and illegal project. Could you explore COINTELPRO’s surveillance, infiltration, discrediting, and disrupting of American political organizations that the FBI viewed as subversive?

[00:33:43] Beverly: I think you’re right that COINTELPRO remains the most notorious program of Hoover’s whole career, and I think for very good reason. COINTELPRO stands for counterintelligence program and what the FBI meant by counterintelligence was not just surveillance, but active disruptive measures against organizations. That it did not like most of those were left-wing organizations, although there were some organizations on the right as well.

[00:34:17] Beverly: So, that meant everything from sending informants into meetings to be disruptive to advocate for violence, or to spread rumors, they had cartoonists on staff, actually, who, you know, made cartoons mocking, say, the Communist Party or other organizations that they didn’t like printing those, so a lot of these kind of low-level and sometimes more extreme disruptive measures. It started out as a program really specifically aimed at the Communist Party, but over the course of the 1960s, it spread out much, much more widely. Lots of it aimed at civil rights organizations. Lots of it aimed at [00:35:00] groups like the Black Panthers at the Student New Left, the antiwar movement, and then some of it also aimed at the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizations that the FBI felt were really beyond the pale.

[00:35:15] Alisha: So, my final question: J. Edgar Hoover served, as you mentioned, under eight different presidents, and was a pioneer in American law enforcement, and contributed to the excesses of the federal administrative state.Can you close by discussing his remarkably complex and sometimes controversial legacy?

[00:35:35] Beverly: One of the things that really interested me about Hoover was that I thought that he represented a set of traditions that he put together from American political life that we don’t see very often put together. One of those is this real belief in career, nonpartisan government service.

[00:35:59] Beverly: Sort of a progressive vision of state power, how experts and professionals, you know, can serve the government. And then on the other hand, this kind of deep ideological conservatism on anti-communism, on race, on religion, on law and order, and he sort of put those things together and I think created the FBI the intersection of those two traditions, which as I said, we don’t, we don’t see put together all that often in our own world.

[00:36:31] Beverly: I think within that, you know, a lot of the most outrageous excesses and I think a lot of the damage that Hoover did tended to come on the kind of political and intelligence side of the ledger, places where he was operating mostly in secret, where he was kind of following his own judgments about who was dangerous, who was not dangerous, who was a real American, who was a threat to the established order and the abuses of civil liberties, the lack of accountability that came on that side of the ledger, I think is a huge part of his legacy. It has what is really what has made him such a controversial and pretty widely disparaged figure in our own day.

[00:37:22] Alisha: For sure. Thank you, Professor Gage. Before we let you go, we would love for you to read maybe a passage in your book.

[00:37:29] Beverly: Great. I’m going to read a passage from right near the end of the book that tries to get at a little of what we were just talking about, which is Hoover’s broader legacy as we might want to understand it in the present: “In the decades since his death, the abuses exposed by the Church Committee, that was in the 1970s, have continued to define his legacy. His name conjures up images of backroom scheming and abuse of power, of secrets and lies and the politics of fear. He has been depicted as a racist and a demagogue, a single-minded seeker of power, a small-minded and twisted man intolerant of even his own desires, and all rightly so. During his lifetime, Hoover did as much as any individual in government to contain and cripple movements seeking racial and social justice, and thus to limit the forms of democracy and governance that might have been possible. His actions damaged the lives of thousands of people, liberals and journalists, civil rights workers and congressmen, Black Panthers and Communists. It is only fitting that his targets should have their say, and that their experiences should help to define his legacy. And yet, there is a certain loss in this image of Hoover as a one-dimensional villain, the embodiment of all that is worst in the American political tradition. For one thing, it makes him a too-easy scapegoat. His guilt restores everyone else’s innocence. It also obscures what once seemed to be an ennobling vision of government service, as a realm where professionalism, self-sacrifice, expertise, and efficiency would reach their highest form. One tragedy of Hoover’s life is that he became what he swore he would never be, and thus undermined the very ideals that he had found so captivating as a young man.”

[00:39:29] Alisha: Very powerful. Thank you so much.

[00:39:29] Charlie: That’s great, Professor Gates. Thank you so much. Really enjoyed that.

[00:39:34] Beverly: Sure. Great. This was lots of fun.

[00:39:49] Charlie: Well, that was a fascinating interview about an absolutely fascinating subject. So, this week’s Tweet of the Week, the Center on Reinventing Public Education reposted an education resource strategies Tweet. Education resource strategies has an article in The74 says it’s time to redesign the high school experience.

[00:40:11] Charlie: And in the piece that’s in The 74 it talks about a vision for what these re-envisioned high schools can look like and how we can get there. So, you can check it out, as I said, in The74. Well, Alicia, as always, it has been a pleasure to talk about some of these education issues and not to mention about the fascinating and somewhat strange, I think it’s safe to say, J. Edgar Hoover. Thank you so much for joining us. I hope we can do this again soon.

[00:40:38] Alisha: Always great to be with you, Charlie. Thank you.

[00:40:40] Charlie: Our guest next week will be Dr. Adrian Mims, Sr., who is the founder and CEO of The Calculus Project. So, that explains why he’s not somebody I’m familiar with since I passed Algebra II. But, anyway, it will be interesting and I hope you can join us next week.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Alisha Searcy and Charlie Chieppo interview Yale Prof. Beverly Gage, author of G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American. Gage delves into the enigmatic life and career of J. Edgar Hoover, tracing his formative years in Washington, D.C., his rise to prominence as director of the FBI, and his enduring influence on American law enforcement and politics. She discusses his early career monitoring domestic radicals to his aggressive pursuit of gangsters like John Dillinger, communists, spies, and Civil Rights-era figures. Hoover’s tenure at the FBI was marked by both innovation and controversy. She closes with a reading from G-Man.

Stories of the Week: Alisha shares an article from Real Clear Education on HBCU’s; Charlie analyzes a white paper from Pioneer on MCAS, NAEP, and educational accountability.

Guest:

Beverly Gage is the John Lewis Gaddis Professor of History at Yale University. Her book G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, received the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Biography, the Bancroft Prize in American History, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Biography, the Barbara and David Zalaznick Book Prize in American History, and the Ellis W. Hawley Prize of the Organization of American Historians. G-Man was named a best book of 2022 by the Washington Post, The Atlantic, Publishers Weekly, The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Smithsonian. In 2009, Professor Gage received the Sarai Ribicoff Award for teaching excellence in Yale College. She is a graduate of Yale University with a B.A. magna cum laude in American Studies and she earned a Ph.D. in History from Columbia University.

Beverly Gage is the John Lewis Gaddis Professor of History at Yale University. Her book G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, received the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Biography, the Bancroft Prize in American History, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Biography, the Barbara and David Zalaznick Book Prize in American History, and the Ellis W. Hawley Prize of the Organization of American Historians. G-Man was named a best book of 2022 by the Washington Post, The Atlantic, Publishers Weekly, The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Smithsonian. In 2009, Professor Gage received the Sarai Ribicoff Award for teaching excellence in Yale College. She is a graduate of Yale University with a B.A. magna cum laude in American Studies and she earned a Ph.D. in History from Columbia University.

Tweet of the Week: