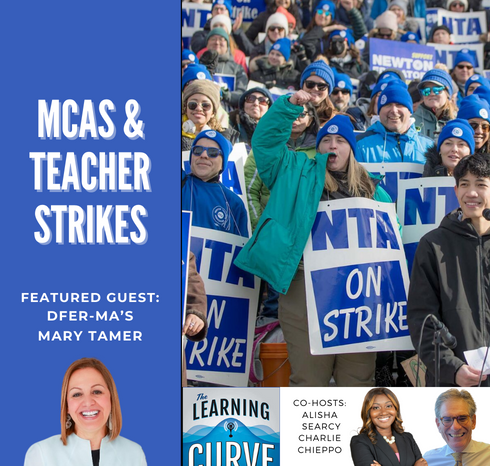

DFER-MA’s Mary Tamer on MCAS & Teacher Strikes

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve: Mary Tamer

[00:00:00] Alisha: Welcome back to The Learning Curve podcast. I am your co-host this week, Alisha Thomas Searcy, and joined by my good friend, Charlie Chieppo. Hey, Charlie.

[00:00:32] Charlie: Hey, Alishaia. It’s great to be co-hosting with you again.

[00:00:36] Alisha: As always, I always look forward to it. We’ve got a great show today, but of course we have to start with our Stories of the Week. Would you like to go first?

[00:00:46] Charlie: I’m happy to go first. You’re very kind. My story comes out of Alaska of all places. In response to a Harvard study that found that Alaska charter schools outperformed traditional public schools by more than in any other state, Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy has said he’d veto any bill that just increases public education funding without also planning to establish more charters. So, me being the opinionated guy I am, I believe that the responses to him really shine a light on what, in my view, are many of the big problems with public education today. So, the pushback includes — and all of you who have any familiarity with charter schools will know all these well — well, the study had a very small sample size.

[00:01:36] Charlie: They complained that there’s no transportation provided to some of these charter schools. Remember, this is Alaska. These can be some very remote schools. Some don’t have kitchens and can’t provide free or reduced-price lunches. The students who attend the charters are likely not representative of the broader state population, and that these charters require a high level of parental commitment.

[00:02:00] Charlie: In my mind, here’s the deal. Alaska has among the nation’s lowest performing public schools. The average charter school student in Alaska scored an entire year of learning ahead of other Alaska public school students. And the study results were adjusted for race, ethnicity, and other demographic differences. So, the bottom line to me is, I mean, wouldn’t it make sense to maybe just provide charter students with transportation to these schools or provide funding? To build kitchens in the schools that don’t have them? I mean, instead of coming up with a million reasons not to do it and not to expand these schools that have been so successful, why not give more students a chance to attend schools that are so dramatically outperforming the other public schools in the state?

[00:02:52] Charlie: And again, remember, the bottom line here is that these are among the lowest-performing public schools in America that the [00:03:00] traditional public schools in Alaska. Look, I get it. Alaska deals with challenges that probably no other state does in case in terms of vast different distances, sparse population, and things like that. But anyway, that is my story this week.

[00:03:16] Alisha: and it makes sense and Charlie. I’m not sure why in education we like to have these false choices it’s possible that you can improve the traditional public schools right and make sure they have the resources they need as well as make sure the charter schools have the resources that they need, so at the end of the day all students are successful right regardless of the kind of public school they go to. How about that?

[00:03:38] Charlie: No, yeah, exactly. That is right. And look, you and I are both parents too. And I sometimes I just, I just find it astonishing sometimes that more people don’t have their hair on fire over what’s going on in a lot of, public education sometimes, but yes. It is what it is, you know.

[00:03:54] Alisha: It is what it is. Well, my, if my hair can be on fire, it certainly is for all of the things and speaking of being parents, Charlie, so I’ve found an interesting story from the hill. The days of optional SAT scores may be coming to an end.

Charlie: Yeah, I’ve been reading about this.

[00:04:17] Alisha: Yeah. And so it’s interesting to me and of course, very pressing because I have a high school junior. And of course, we’re having conversations now about SAT and college choices and all of that. And so I found this article to be interesting for a couple of reasons. Obviously, and I think people know that the reason that SAT scores um, even became optional initially because of COVID and students not having access to the test sites, right? And not being able to get there because of restrictions. And then I think there was a important conversation that was also brought forth around the equity of scores, you know, who has access to the resources.

[00:04:54] Alisha: Whether it’s to go to some sort of training or, you know, test prep course or [00:05:00] whether or not you have the ability and the resources to take multiple tests, you know, so you can get the best score, whether or not they are racially objective, all of those different things. And so, I think these are important conversations to have and, what my question about this article — and specifically it talks about how Dartmouth is announcing this week that they are going to be reinstating the requirement for SAT or ACT test scores — and so the idea here is they’re hoping that more colleges won’t come on board. And so, in my little research, I found that I think it’s about 1,400 schools currently across the country are either test optional or don’t require a test at all. And so, my question is whether or not enough research has been done, right? Enough studies have been done to really determine how important these test scores are. I know for me I didn’t have the highest SAT score, but it certainly was not a predictor of my ability in undergrad or graduate school for that matter. And so, I do think it’s just a small snapshot as any assessment would be.

[00:06:08] Alisha: We talk about the same thing in K-12 and it doesn’t give the whole picture of a student’s ability. At the same time, it does give you some information. But I think before colleges start moving back to automatically making these requirements, I think we ought to study this a little bit more and really get a sense of, you know, these graduating classes, the components of the classes that they’re now making up in these colleges that are test optional and just see what the impact has been and if it’s absolutely necessary.

[00:06:37] Charlie: Well, I have to tell you. Alisha, your observations really track with my experience. I actually spent almost eight years in college admissions reading those applications. And I had the same reaction, which is that, you know, I think there is a value to them. They certainly are not the entire picture. I think for me, sometimes where they did have a value, was sometimes you saw a student whose performance was very good and their scores were very, very low. And that’s one that sort of makes you wonder sometimes about, what the school’s like, you know, what the curriculum they’ve had has been like, and, basically that that school may not have been doing that student any favors, but I concur with your overall view on that one.

[00:07:19] Alisha: Well, thank you, and I didn’t know that you have that background, so we may be calling you for a little advice if that’s okay.

[00:07:25] Charlie: You certainly may. I understand that my experience was about a hundred years ago, but I’m happy to, help however I can.

[00:07:32] Alisha: Awesome. I’m learning that this whole thing is a science, so more to come.

[00:07:38] Charlie: Yeah, a more complicated science than it was when I was doing it.

[00:07:41] Alisha: I’m sure. Next up, our guest today is Mary Tamer. She’s the executive director of Democrats for Education Reform, Massachusetts.

[00:08:06] Alisha: Our next guest is Mary Tamer. She’s the Executive Director of Democrats for Education Reform, Massachusetts. She’s a longtime education advocate and Democratic activist who is a product of the Boston Public Schools. A former BPS parent, a former member of the Boston School Committee, and past president of the League of Women Voters of Boston. Prior to joining DFER, she worked for School Facts Boston as the Education Research Director and with the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association. Mary earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in English and journalism from the University of New Hampshire and an EDM in Education Policy and Management from the Harvard University Graduate School of Education.

[00:08:50] Charlie: Welcome, Mary Tamer. It’s great to have you here.

[00:08:53] Mary: Thank you so much, Charlie. I’m happy to be here.

[00:08:56] Charlie: As noted in your bio, you’re a graduate of Boston Latin and a former member of the Boston School Committee. Would you share with us some of your background, early educational experiences, and work on K-12 education policy in Boston?

[00:09:08] Mary: Yeah, absolutely, because I think it was because of my own time as a student in the public schools that really shaped so much of my worldview and why I work in education policy now. I am the proud granddaughter of immigrants from Syria on my mother’s side and Lebanon on my dad’s side. My mom actually was raised — both of my parents were raised in Arabic speaking households — and my mom was actually rejected from the Boston Public Schools when her parents tried to get her into the schools in Brighton because she didn’t speak enough English. And so, we didn’t have protections in place back then for English learners and I, you know, remember even as a child, my mom sharing the story with my sisters and I, because it was such an impactful moment in her life to be turned away from the school right down her street, which she had so looked forward to going to as a little girl. And so, I think that, you know, my own experience in the Boston Public Schools was a time of tremendous angst and discord. It was in the middle of desegregation. I felt extremely fortunate to start at a school that was right down the street from my grandparents to family house, which is where my family and I lived.

[00:10:23] Mary: And so, I started at the same elementary school my dad had gone to. And while I thrived in school, my older sister really struggled from elementary school on. And so, while my younger sister and I were fortunate to be accepted into an advanced work program, my older sister went to the Lewenberg, which was a middle school in Mattapan that had been in years of successive failure. It was ultimately closed. And then after the Lewenberg my sister went on to English High School. I was on the Latin School track and was extremely fortunate to go there. But at the time that I was having this incredible educational experience, my older sister was falling through the cracks of a high school where my dad was quite ill at the time and my parents really had their hands full with that. And my sister appeared to be going to school every day and in fact missed almost an entire month of school her freshman year, just in the first part of her freshman year. And yet not one adult in the building ever called my parents. And I think what that did for me as I got older and just saw — and my sister ultimately dropped out of school after her freshman year went to an alternative program that she also dropped out of and then passed away very young. And so, what I see all these decades later is that we still have far too many children, whether it’s in Boston, whether it’s in other districts, who fall through the cracks.

[00:11:55] Mary: And I know because my lens has been Boston for so long, since this is where I grew up, and this is what I call my home. Why we accept the fact that in a family of three that two of the kids did fine, but there was that one that didn’t and that we accept failure a little too easily. And we have for decades. And I think that is really what propels me to do the work that I do every day.

[00:12:21] Charlie: That’s great. You know, Mary, the first part of your story so resonated with me because my mom would always tell the story about how she didn’t graduate from high school until she was 20, because she came to the United States from Italy when she was nine and didn’t speak a word of English and they just put her in class until she figured it out, you know, so obviously it took a little time.

[00:12:57] Mary: Yeah, and I think the sad thing, Charlie, is when, you know, when you come from an immigrant family, I think at that time it was all about assimilation and, you know, my parents spoke Arabic fluently, and frankly used it as their secret language. So my sisters and I didn’t know what they were talking about. But what that also meant for me is that I missed out on having that second language in my life. And my older son is now fully fluent in Arabic and my jealousy over that knows no bounds, because we really do need to embrace bilingualism, multilingualism in this global world, this global economy that we all operate in. And so, I love that we’re in a place now where we really can for the most part, you know — I hope most of us do embrace multilingual and bilingual folks — because that is really such an incredible advantage to have.

[00:13:40] Charlie: Absolutely. I’m, in the same boat. I’m the youngest of four and I was the only one who didn’t grow up speaking Italian. So I desperately and fruitlessly for the most part trying to learn it now. Anyway, so, back to Massachusetts — the 1993 Massachusetts Education Reform Act included [00:14:00] a highly progressive state funding formula testing, MCAS we call it in Massachusetts, and standards, charter public schools, district accountability, all of which has been a historic success. Could you talk about the Education Reform Act’s national and international successes, how MCAS has been a keystone of the Bay State’s remarkable achievements in K-12 education.

[00:14:23] Mary: Yeah. You know, we just did our, our organization did a deep dive on, the 30th anniversary of the act last June. And it really was, I think, such an amazing experience for our staff to just take a look back and to, and to really have the opportunity to remark on, like, where was it incredibly successful? Where did we fall short? And where do we need to go next? And I think that \when you consider that prior to the act’s passage 30 years ago, that Massachusetts was somewhere in the middle of all the states in terms of our achievement levels — and until very recently, we’re still number one in a number of categories and I think number one overall in the country — but to think of how long Massachusetts has been number one when compared to all the states when it comes to educational outcomes. And now I always have to say we’re number one — there’s a caveat because we’re number one for some as my friends at Ed Trust wrote in really brilliant report that highlights the widespread disparities that we see between white students, Asian students and black and brown students, low-income students, our English learners and our students with disabilities.

[00:15:38] Mary: And so, we have to be honest about where the success is and where we still have a long way to go. But that being said, what the act did was we saw, you know, graduation rates go up dramatically. We saw dropout rates go down dramatically. We had, as you mentioned, MCAS, you know, starting in 1998, a new system of testing accountability. And that really has, I think, vastly improved what we knew to be happening prior to 1993, which was a real, I mean, just widespread disparity and discrepancies in terms of what a diploma meant. And I think the 1993 act really solidified not only Massachusetts’ standing in the country and in the world, frankly, because I mean, when you are looking at international testing and Massachusetts is coming, you know, second only to Singapore. Clearly this was a really dramatic, comprehensive step in the right direction when it came to our funding formulas, the creation of charter schools, and giving families a choice when it came to where they wanted to send their children to school.

[00:16:52] Mary: The way teachers are certified and the rigor of that process. Just so many good things, frankly, Charlie, and it’s really wild to think that it’s been 30 years since we’ve had any kind of education reform act of that magnitude here in Massachusetts.

[00:17:08] Charlie: Yeah, that’s right. You know, at Pioneer, we were lucky enough to have Tom Birmingham working with us for the last few years of his life until he passed away last year. And, you know, he was one of the co-authors of that and stories he would tell about, what he saw prior to 1993, which was obviously one of the things that was catalyst behind the act. Some of those stories were just unbelievable. As you say, there’s, more to do, but it’s certainly changed our world for the better, no doubt about that.

[00:17:35] Mary: It did, and it was a real bipartisan act too, which I think, you know, it’s important to mention that it was a Democratic Legislature and a Republican governor, Governor Weld. And like any good piece of policy, there’s a lot of negotiations at times there’s compromise, but this is a bill that really didn’t compromise when it came to putting students first.

[00:18:00] Charlie: Well put. I mean, it’s really, it’s quite amazing in retrospect.

[00:18:03] Mary: Yes. Completely agree. Yeah.

[00:18:06] Charlie: Well, looking at it sort of from a national perspective after decades of Democratic presidents like Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, numerous center-left state leaders across the country, supporting, testing charters and accountability. The teachers ‘unions are now clearly ascendant within the Democratic Party. Could you talk about the national political changes within the party on K-12 education policy?

[00:18:30] Mary: Yeah, absolutely. You know, what’s so interesting to me, Charlie, is how, just how much it varies wildly state by state, right? And like, when I look to the work that my colleagues are doing in Colorado at Democrats for Education Reform and Education Reform Now in Colorado, like they have made incredible gains and have been really ahead of the curve in terms of some of the education policy that they have passed in Colorado. There are other places. It’s interesting because even here in Massachusetts and I know we are considered to be a very blue state, I think a lot of people are unaware of the fact that 61 percent of our electorate are actually unenrolled voters since we don’t have an Independent party per se in Massachusetts, you’re either Republican, Democrat, or you’re unenrolled and 61 percent of our voters are unenrolled.

[00:19:21] Mary: And so, when we look at how the teachers’ union has done here in Massachusetts, especially when it comes to getting legislation passed, it frankly hasn’t been so great. It was just last week that one of their key bills that was part of a pretty extreme legislative platform that they put forward just over a year ago was to legalize teacher strikes here in Massachusetts. And as it turns out, that bill was put to study, which means it’s not going anywhere. And so, I think we see signs of — even in a state like our own — I think the power varies, right? And what they’re able to accomplish legislatively, I think, varies wildly as well. At the national level, you know, President Biden is not the ed reformer that President Obama was. He is married to, as we all know, he’s married to a union member who is a teacher. And so, I think that has at least from the perception, I believe, you know, it has been something that has been challenging in the ed reform space. Yet so much of what we are able to do does happen at the state level.

[00:20:40] Mary: And I know for the work that we’re doing here in Massachusetts, including you know, last week, our literacy bill was voted out of committee, which we are very happy about. And this is something that the teachers’ union has not been supporting. You know, when we look at the numbers, that less than 50 percent of elementary school [00:21:00] students are reading on grade level in Massachusetts and consider that statistic and knowing that we are number one in the country, I think it’s absolutely horrifying. And so, we need to really question why is the teachers’ union against moving to a research and evidence-based reading curriculum when we know that less than half of the kids in Massachusetts are reading on grade level? It’s an absolute mystery.

[00:21:26] Charlie: But it was encouraging to hear the governor oppose the bill that would have made teacher strikes legal and also to really highlight the literacy issue in her state of the state address.

[00:21:38] Mary: Yes, I completely agree. we were really uncertain, I think with Gov. Healey, as you know, coming into this role of governor as a long-time attorney general who really didn’t have to talk a lot about education. We’re so pleased to see that, given how poor the literacy outcomes are in Massachusetts, that she and Secretary Tutwiler have named this as their top priority as it should be, because if children aren’t learning how to read Charlie, what else are they going to be able to do in school? I mean, let’s be honest. It is the most important skill we can teach to our children at the earliest possible age in order for them to have a fighting chance in their educational careers.

[00:22:25] Charlie: No, that’s so true. So leading DFER Massachusetts, you’ve just assembled a diverse coalition of education reformers and advocates to push back against the Massachusetts Teachers Association and their statewide ballot effort to scrap MCAS as a high-stakes test. Would you talk about the MTA’s drive to undo MCAS as a central element of Massachusetts education reform?

[00:22:50] Mary: One of the things that became clear, Charlie, is through the pandemic and through our periods of school closures is we were hearing louder and louder calls for an end to testing, like frankly, any kind of standardized testing. And, you know, these calls were happening prior to the pandemic, but it seems that the MTA and others took an opportunity during a really, really terrible time for our kids and families, for our education systems, to seize an opportunity to say testing is really bad, we really shouldn’t do this. And so, the ballot question I think is step one in a longer-term goal to remove any kind of standardized testing and accountability from our schools. And I do think it’s a dangerous step forward. One of the things we know, especially looking at the data, and we have been moving in the wrong direction for a number of years, even prior to the pandemic. And so this is exactly what standardized testing allows us to see. And what MCAS allows us to see is we can compare student groups. We can compare by grade, by student category, you know, let’s look and see how English learners are doing against non-English learners. How are our students with disabilities doing? How are our black and brown students doing, our low-income students? And so, when we see the changes in these scores and when we see the scores going in the wrong direction, to all of a sudden say, we want to do away with this.

[00:24:34] Mary: You know, we have used the analogy of, when my boys were younger and weren’t feeling well, I would use a thermometer to take their temperature to determine like, do I just give them some, Tylenol? Do I need to take them to the pediatrician because their fever’s that high? You know, the thermometer didn’t tell me everything I needed to know, but it told me enough to make a determination of what my next step was going to be.

[00:24:58] Mary: And that’s exactly what MCAS is supposed to be doing in our classrooms and for our teachers and students. It’s supposed to give teachers a sense of where are my lessons resonating? And where did I miss the boat? Like if you as a teacher, see that the child missed an entire section of algebra, like they just didn’t get it. You know, the goal was to use that data as an opportunity for educators to fine-tune their practice to change lesson plans to find better methodologies, to make sure that that following year that you’re, eighth graders are going to be doing better in that section of algebra.

[00:25:38] Mary: And so, I feel that this narrative has been created about the harm of testing. And I think there is far more harm in trying to take away the one standard, the one statewide standard we have for students to graduate, Charlie. And what a lot of people don’t realize is if MCAS goes away, Massachusetts would be one of two states without a statewide standard for graduation, because we do not have curricular standards. We have Mass Core — is a set of recommendations, not requirements — and I think most people are unaware of that fact.

[00:26:17] Charlie: I think you’re absolutely right. Very good point.

[00:26:21] Alisha: Thank you, Mary. I’ve learned a lot listening to you and I, I love your passion.

[00:26:25] Mary: Thank you.

[00:26:26] Alisha: You’re welcome. And so someone who is outside of Massachusetts you know, trying to learn here, and for the rest of our listeners who may not know all of this — so, the MTA is a member entity that has 115,000 members that annually gathers approximately $65 million in largely dues-driven revenue, from my understanding. Can you talk about their political power in Massachusetts, particularly some of their key arguments against is it called the MCAS? And as a [00:27:00] graduation requirement and what pro MCAS advocates, parents and business leaders need to do to preserve this assessment as an objective statewide measure of student achievement?

[00:27:11] Mary: It’s such an important question, honestly, Alicia. And so, I think in terms of their political power, it really is in their resources, which are seemingly endless thanks to member dues. And in addition to the $65 million in annual revenue from member dues, there’s also, they have a number of real estate holdings and we know from past ballot questions that they’ve supported that they will, if needed, liquidate some of those real estate holdings in order to free up cash. And so, at any given time they have, you know, somewhere around $100 million at their disposal to use as they wish.

[00:27:53] Mary: And so, I think because of what I said earlier about their lack of success, legislatively, I believe that is why they know that their one opportunity is to pursue ballot questions, which frankly, it’s a terrible way to legislate. Because often the questions aren’t worded in the best possible way. I think people are not as aware of what the implications are. And I think to that point, you know, one of, I think, the most effective messages that the MTA has, circulated around the state and, when you have 116,000 members, it’s not so hard to do, but that, you know, we are teaching to the test all day. Like this is something that we hear this refrain over and over again, that I’m teaching to the test all day.

[00:28:41] Mary: there’s no room for art, music, you know, any of the other wonderful things that we would all want our children to have. And that is something that I think has taken hold with a lot of parents, with a lot of students. Now I am the mother of two, you know, they’re out of school and out of college now, but my both of my sons attended public school. And I can say with absolute certainty, they were not only getting math and English all day. They thankfully had language instruction. They had science, they had art, they had music, they even had gym on occasion. And so, I think one of the biggest. challenges that we face, and it’s not an insurmountable challenge, is letting people know where the truth lies.

[00:29:24] Mary: Like when you see the hours of testing that take place in Massachusetts on an annual basis, how much time actually is devoted to MCAS. Um, it’s actually nowhere near as bad as how it is portrayed. And so, there is such a significant divide between the narrative that is being shared by the MTA and the actual truth of what’s happening on the ground and in classrooms.

[00:29:49] Alisha: Makes sense. I want to talk about the [MTA] president, Max Page. And again, I’m an outsider, so this is just my perception, but it seems like many of the recent MTA efforts have been driven by Mr. Page, whose worldview can be considered controversial, let’s say. And so, can you talk about how Mr. Page has used some of his protest politics as the means to mobilize members and leverage the rhetoric to achieve his union’s political goals?

[00:30:17] Mary: Yeah, absolutely. I think we just saw a perfect illustration of this, just over a week or so ago when we saw the Newton Teachers Association go on strike for two weeks. And so, all students in Newton and 20 percent of the population is students with disabilities. They also have over 400 students METCO students from Boston. This is an integration program that’s been in place for decades. And so, it’s mostly students of color who are sent to suburban districts, including Newton. And so, 11 days out of school, and it got to a point where I think parents were really upset.

[00:30:57] Mary: I’ve talked to so many Newton parents. I had people calling me. What do we do? How do we mobilize? And I think that this is something under the Page leadership that strikes, I think this was number six in the last year and a half. It is illegal, you know, not only here in Massachusetts for public sector unions to strike, but in the majority of our states, it’s illegal for public sector unions to strike. And so, judges, you know, ultimately the school committee or the school administration will take the teachers union to court, try to get them to come back. Fines are levied, but what we’ve seen happen consistently with all six strikes is that people in the union are just scoffing at the fines. But I think when you’re sitting on $100 million and, you know, even in Newton, I believe it was reported in the Boston Globe that just the Newton Teachers Association alone was sitting on, I think, $1.2 million in their bank account. And they ended up, with, I think, $675,000 in fines for an 11-day strike.

[00:31:59] Mary: But the cost of the police alone, for example, to be present during these strikes — which were pretty loud and long outside of Newton City Hall — was over a million dollars. And so, there’s significant costs involved, not to mention the costs that you really can’t quantify in terms of what does it mean to a child on the autism spectrum when they haven’t had services for 11 — well, really, it’s 15 days when you consider the weekends — but to be out of school for over two weeks in the amount of dysregulation that that can lead to for a child. I think when we see the unbelievable suicide rates and mental health challenges that our youth are facing across the country, but here in Massachusetts as well, being in school and having that consistency, having those two meals a day for low-income students. Now, this is not a low-income area. But even areas like Newton have a percentage of low-income students who are reliant on school food in order to get two of their meals a day. To not take any of that into consideration, it’s just, I have to be honest. I do not think this is helping their cause.

[00:33:09] Mary: And even as we face this ballot question, what the Newton teachers did over this two-week period of time did not breed a lot of goodwill on their part. And sure, there were, parents that stood with them and supported them. But I would say at this point in time, there’s far more parents who are still seething with anger over what transpired in Newton, just a week and a half ago.

[00:33:32] Alisha: Wow. I think it’s so important that you highlight the impact that this has, you know, you understand workers want certain things, you know, people, as unions and others, right? Organize and mobilize themselves and they certainly deserve a voice. But when you think about the real impact that it has on students and families and municipalities, as you mentioned, just the cost of police protection, that’s really important to point out. So, thank you for that. The MTA’s endgame on illegal teacher strikes — and I say that because you just mentioned that striking is illegal under the law — seems to be using them as a contract negotiating tactic, but also seeking to perhaps overturn the state law prohibiting public-sector union strikes. So, on Beacon Hill and across the state, what are the other implications of these teacher strikes on the future of the K-12 education reform movement, if you will, in Massachusetts?

[00:34:28] Mary: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. I mean, really come back to, I do not think this is helping their cause. I do not think that this is generating or building goodwill toward what they’re trying to achieve. I work for an organization that puts students first, and I’m very proud of that. I do believe in collective bargaining agreements. I believe, you know, we live in a state where, we have so many unions that absolutely thrive here, but when it comes to striking, I don’t understand, when we have decades of history of settling collective bargaining agreements without striking, it is very clear to me that this is purely political. I think the fact that the state Legislature, as I mentioned earlier, has rejected their bill, which would legalize the right for the public-sector unions to strike here in Massachusetts that was outright rejected by a fully Democratic, you know, pretty much almost fully Democratic Legislature.

[00:35:36] Mary: And so that really speaks volumes. I mean, we’ve had our Secretary of Education, our governor, our Speaker of the House, I’ll say like this is not what should be happening and it certainly should not be happening. After three years of disrupted learning for our students and what that has brought, which is a mental health crisis of proportions that we’ve never seen before. Incredibly high suicidality rates among our children. To not consider the vulnerability of so many of our children for so many different reasons and to use them as pawns in a political battle is egregious to me, I truly don’t know how anyone could put their own needs ahead of the needs of children. When again, we have historically settled collective bargaining agreements on an annual basis for decades without strikes. Why all of a sudden under new leaderships are strikes so essential to settle these contracts?

[00:36:47] Mary: It is clear that it is under the leadership of someone who really wants to disrupt the norms here in Massachusetts, to put parents and families at such a clear disadvantage. And to frankly, threaten the future of our children and what they need and deserve from us as the grownups in the room. At the very least we can act like grownups and put the children first.

[00:37:16] Alisha: And we’re going to call that a mic drop moment. Thank you, Mary. Wow. Phenomenal. Thank you so much for being with us. Just well said again. Appreciate your passion and. the need for us to put kids first. So, thank you for the time today.

[00:37:34] Mary: My pleasure. So nice to meet you.

[00:37:36] Charlie: [00:38:00] That was a great interview. Mary Tamer’s long been one of my favorites. So, I really enjoyed that.

[00:38:10] Alisha: Learned a lot for sure.

[00:38:11] Charlie: As always. Exactly. Exactly. So the Tweet of the Week this week is from The74. And it is that according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, public K-12 schools added 160,000 jobs in 2023. And I’ll tell you, I think this is particularly an interesting issue to look at right now, given that, the federal funding that funded so many of those jobs is now going away. And so, I think that sort of keeping an eye on, public school finance is going to be very interesting in the weeks and months.

[00:38:44] Alisha: Yeah. And we keep hearing about this fiscal cliff that’s coming for schools and jobs are certainly connected to that.

[00:38:51] Charlie: So, no doubt about it. Well, Alisha, as always, it is an absolute pleasure to, get to do this together. So, thank you very much.

[00:38:58] Alisha: Absolutely, Charlie. Great to be on with [00:39:00] you.

[00:39:00] Charlie: And I’m glad to be your admissions consultant.

Alisha: Thank you very much. Very excited about that. Well, next week we’ve got professor Benjamin Smith. So, we were looking forward to that. He’s the professor of Latin American History at the University of Warwick in the UK and author of The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade. That’ll be interesting. I’m definitely going to tune into that one.

[00:39:25] Charlie: That sounds fascinating.

[00:39:27] Alisha: Indeed. See you next week.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Alisha Searcy and Charlie Chieppo interview Mary Tamer, Executive Director of Democrats for Education Reform, Massachusetts. She focuses on the historic impact of the 1993 Massachusetts Education Reform Act on the commonwealth’s students’ high achievement on national and international measures. She explores the politics of the Massachusetts Teachers Association advocating against the MCAS test as a graduation requirement. In closing, Ms. Tamer also discusses the rise of teacher strikes and their implications for education reform in the Bay State.

Stories of the Week: Alisha talks about an article from The Hill on optional SAT scores; Charlie reviews a story from Anchorage Daily News on Alaska charter schools expanding.

Guest:

Mary Tamer is the Executive Director of Democrats for Education Reform Massachusetts. She is a longtime education advocate and Democratic activist who is a product of the Boston Public Schools (BPS), a former BPS parent, a former member of the Boston School Committee, and past president of the League of Women Voters of Boston. Prior to joining DFER, she worked for SchoolFacts Boston as the Education Research Director, and with the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association. Mary earned a B.A. in English and journalism for the University of New Hampshire, and an Ed.M. in Education Policy and Management from the Harvard University Graduate School of Education.

Mary Tamer is the Executive Director of Democrats for Education Reform Massachusetts. She is a longtime education advocate and Democratic activist who is a product of the Boston Public Schools (BPS), a former BPS parent, a former member of the Boston School Committee, and past president of the League of Women Voters of Boston. Prior to joining DFER, she worked for SchoolFacts Boston as the Education Research Director, and with the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association. Mary earned a B.A. in English and journalism for the University of New Hampshire, and an Ed.M. in Education Policy and Management from the Harvard University Graduate School of Education.

Tweet of the Week: