New Hampshire Tax Burden Dramatically Less than Massachusetts

The Granite State’s “live free or die” mentality perfectly describes its minimalist taxation policy. With no income or sales tax, New Hampshire’s tax burden is a fraction of what it is in Massachusetts. But is this strategy really in the best interest of New Hampshire residents?

Overall Tax Burdens

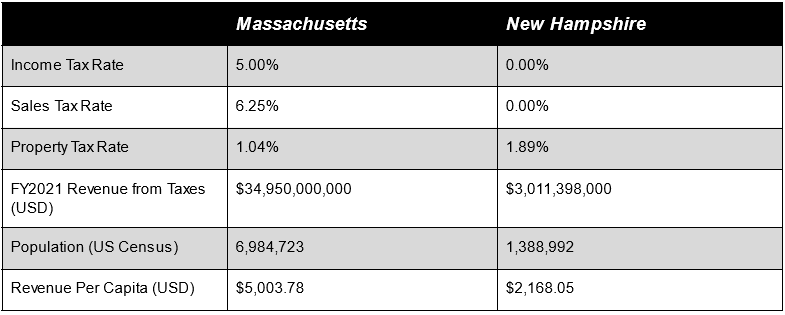

New Hampshire’s tax revenue in 2022 was about $3 billion, compared to about $35 billion in Massachusetts. Those numbers average out to $2,168 per capita in New Hampshire and $5,003 per capita in Massachusetts (see figure 1). That means Massachusetts collects more than twice as much revenue per person than New Hampshire.

Figure 1: A table of tax figures. Average property tax rates for each state collected from tax-rates.com. Income and sales tax rates were collected from official government websites for NH and MA. Revenue from taxes for Massachusetts and New Hampshire was collected from each state’s FY 2021 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (ACFR). Revenue for Massachusetts is also available at the Pioneer Institute’s MassOpenBooks website. The MA ACFR lists revenue from taxes explicitly on page 23 and the author calculated revenue from taxes for NH using the sum of the line items considered “general revenues” on page 21 of the NH ACFR. Population numbers are from the US Census Bureau.

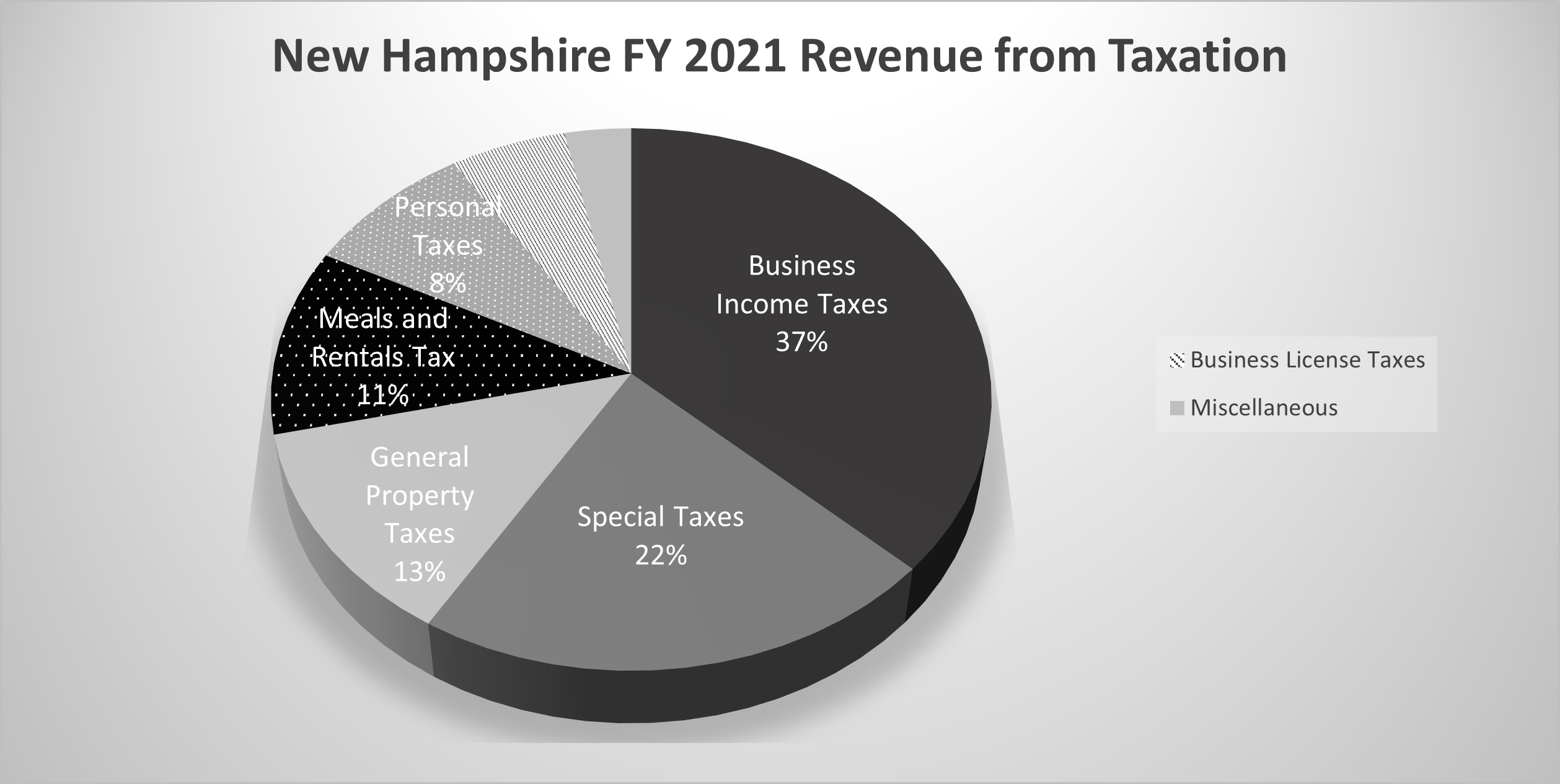

State taxes typically include personal and corporate income tax, property tax, sales tax, estate tax and taxes on investment income. In Massachusetts, the majority of taxes are collected through the personal income and sales taxes, while New Hampshire relies on a business income tax, along with many other small sources of revenue.

In Massachusetts, income and sales taxes account for 78 percent of state revenue; in New Hampshire, they do not exist. New Hampshire’s income tax rate is zero, and there is no sales tax. Instead, New Hampshire levies business taxes, property taxes, and a “meals and rooms” tax that account for the majority of its unrestricted tax revenue.

New Hampshire has the second highest property tax rate in the country, according to tax-rates.com. It collects 1.89 percent of assessed home value each year on average, but local governments receive the majority of it to pay for schools and other municipal expenses.

New Hampshire’s other major tax revenue streams are business taxes and the “meals and rooms” tax. The state collects a 7.7 percent tax on business income that supplies 37 percent of NH tax revenue. The 8.5 percent meals and rooms tax accounts for about 11 percent of tax revenue (see figure 2).

Figure 2: New Hampshire FY2021 revenue from taxation by source. From the New Hampshire FY2021 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report available here.

Tax Exporting

Tax exporting is when a state tries to collect tax revenues from residents of other states. The meals and rentals tax is an example of tax exporting because it targets tourists who are more likely to spend money on hotels and restaurants.

New Hampshire also engages in other forms of tax exporting. They have placed state-owned “duty-free” liquor stores at major border crossings to entice non-residents to contribute to state coffers. Like many other states, they also collect tolls on major highways to pay for road repairs.

New Hampshire has also tried to shield its residents from Massachusetts’ tax exporting. They took Massachusetts to court over its collection of income taxes from New Hampshire residents working in Massachusetts. Ultimately, the Supreme Court rejected the case and allowed Massachusetts to collect income taxes on its workers residing in New Hampshire.

Tax exporting is a concept that policymakers in New Hampshire are keenly aware of. These policymakers leverage tax exporting to reduce New Hampshire’s tax burden to well below half that of Massachusetts.

Low Taxes, but at What Cost?

While researching this blog post, I called up a very friendly man from the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration who told me a story about a small town in New Hampshire. He said the town recently reduced their school budget by half amid widespread tax cuts throughout the state.

The townspeople reacted with shock and disbelief. They convened a town meeting days later and overruled the decision that would have cut the budget to less than $10,000 per student annually. This is a reality check that the over-zealous pursuit of tax cuts has to stop somewhere. The story also highlights something that Massachusetts does better than any other state – provide high quality public education and healthcare coverage to low income residents through MassHealth.

Massachusetts and New Hampshire clearly have dramatically divergent taxation strategies that have produced different outcomes. Which strategy you prefer might just determine which side of the border you call home.

About the Author: Joseph Staruski is a government transparency intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is currently a Master of Public Policy Student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He was previously an opinions columnist with the Boston College student newspaper, The Heights, and an Intern with the Philadelphia Public School Notebook. He has a BA in Philosophy and the Growth and Structure of Cities from Haverford College. Feel free to reach out via email, LinkedIn, or write a letter to Pioneer’s Office in Boston.