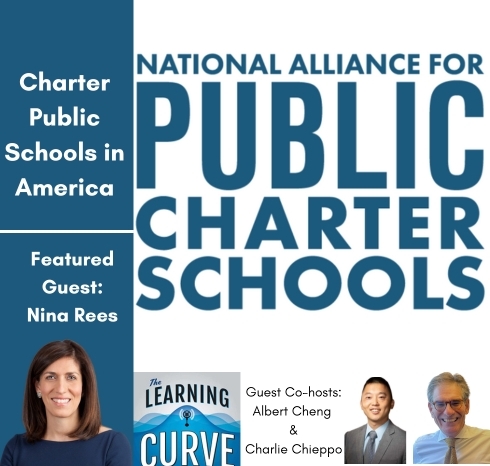

National Alliance’s Nina Rees on Charter Public Schools in America

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Transcript with Nina Rees 11/22/23

[00:00:00] Albert: Hello everybody, welcome to another episode of The Learning Curve podcast. I’m your host today, or one of your co-hosts, Albert Cheng, from the University of Arkansas and with me is Charlie, Charlie, good to see you again.

[00:00:37] Charlie: Good to see you again, Professor Cheng. Great to be here. Looking forward to today’s episode.

[00:00:42] Albert: Yeah, yeah. We got some exciting stuff on the docket. We have Nina Rees going to talk about charter schools. And actually, speaking of charter schools you have a new story related to charter schools, right?

[00:00:53] Charlie: Yeah, this sort of caught my eye. It comes out of my backyard here at Harvard, and it’s from Paul Peterson and M. Denise Shaquille. These folks are from the Program in Education Policy and Governance at Harvard, and it’s called the Nation’s Charter Report Card. And what’s interesting about this study is that it’s the first comparison of charter school student performance across states based on NAEP tests and adjusting for background characteristics. So, the study covers from 2009 to 2019. Interestingly, when you adjust for the, again, when you adjust for the background characteristics of students the states that had the charter schools that performed the best were Alaska, Colorado, and Massachusetts. And the states that performed the worst were Hawaii, Tennessee, and Michigan. I was pretty interested in what the national demographics of charter schools would look like. Turns out that they for this study, there were 32 percent white, 31 percent Hispanic, 30 percent black, and 4 percent Asian.

[00:02:00] Charlie: And obviously, when you’re talking about demographics in charter schools or in education generally we’re talking about achievement gaps very often. There are big racial gaps when you compare white and African American students, the states or I should say the jurisdictions with the biggest gaps were D.C., Missouri, and Wyoming. And the ones with the smallest gaps were Oklahoma, Arizona, and New York. Interesting, huh? Yeah, and when you compare white and Hispanic students, the biggest gaps were again D.C., this time followed by Pennsylvania and Delaware, and the smallest gaps were in Oklahoma, again, Louisiana, and Illinois. So clearly there are particular achievement gap issues in D.C., and I sort of wonder what’s happening in Oklahoma that they are much smaller.

[00:02:53] Charlie: A few very interesting findings for those of us who have been in the charter school world. There’s very little, well, not little. There’s modest correlation, the author said, between the rankings and those for overall public school performance. In other words, it’s not just states that have the best overall public school performance that came out best in the charter school rankings. The other things that were interesting to me as we look at these issues were that students in charters that were authorized by the state education agency generally did better than those that were authorized by a school district or another local agency, and that students that are in charters that are part of nonprofit networks do better than those that are in a freestanding school or for-profit school.

[00:03:45] Charlie: I found all that to be very, very interesting. Now, there’s one big caveat, which was, like I said at the beginning, this covered 2009 to 2019, so a ten-year period. But as we all know, a lot has changed since 2019 in education. So, obviously performance was dramatically affected by the pandemic. And the other thing is that, evidence suggests that chartering enrollment has expanded considerably since then. So, as often is the case in life, it seems that the ink isn’t even dry and this is already ripe for an update. That’s the way the world works. But anyway a report that I thought was interesting and important, and I just wanted to bring it to people’s attention.

[00:04:24] Albert: Yeah. We’ll have you ask our guest Nina her take about this. Exactly. We will do that. So, she’s got a lot to say. And I’ve got a lot of thoughts and, how actually some of the things you, just a quick reaction. It lines up with some of the findings from the most recent CREDO study they just released.

[00:04:40] Charlie: There’s a little section in here about, the difference in what they’re doing and what CREDO is doing. Uhhuh, which is, you’re probably a little bit better when it comes to the methodology, these kind of things that was helpful for me to get clarity on exactly what they’re measuring here.

[00:04:54] Albert: Well, that’s going to be fodder for plenty of discussion for the years ahead. Why some states are better than others or whatnot. So, I’ve got another new story here, Charlie. you and I have talked about math quite a bit.

[00:05:07] Charlie: Everything I know about math I learned from you!

[00:05:08] Albert: Yeah. Well, here’s something I just learned. There’s a new story out of the Hechinger Report about a study that some professors the state of Alabama have conducted. So, they did the survey where they asked university professors what they think kids in secondary school need to learn in order to be ready for or just really what do they need to learn in math? And so, really, there’s two main, I guess, takeaways here. One is if, according to the survey math professors think that for those that want to major in STEM, that what they’re currently getting in high school math isn’t good enough. And that actually there’s a lot of stuff that maybe I should, I don’t know if I’m characterizing it correctly, but you know, the algebra to calculus sequence is still necessary, but there’s still a lot that they need to cover. It seems that they’re not quite satisfied exactly with that sequence. And I don’t know if they just thinking back to that episode a few weeks ago with Jim Stigler, I wonder if some of the reasons for that is would line up with some of Jim’s observations.

[00:06:16] Albert: But the other thing that they mentioned was the vast majority of students aren’t going to go into STEM field necessarily. they even estimated 80 percent high school students aren’t going to go into STEM. And for those students, the traditional algebra, trig, pre-calc, calculus sequence is, they’re using the word unnecessary — and so that begs the question, well, what should they be learning instead? And they listed a few things which I generally like. I especially liked their recommendation — this again, this is university professors on a survey math professors on a survey — high school math should emphasize reasoning and critical thinking skills, the ability to see the beauty of math and have math inspire wonder. It got my amen and my cheer for that. And then at the same time, they also suggested that high school math ought to increasingly emphasize data analysis and statistics so that’s kind of the more practical side. Me as a pure math guy, I guess I have a thing against the applied stuff, although I do the applied stuff for living, but even so, I think that’s kind of reasonable.

[00:07:23] Albert: We’ve undergone this data revolution and some practical training, I can see as having value, and so insofar as you’re going to do practical training maybe they have some data analysis and statistics might be the way to go and certainly those aren’t the typical emphasis, emphases you see in in high school math. So, yeah, I don’t know, that’s kind of caught my eye and certainly is provoking a lot of thought on what to do with math curriculum at the high school level.

[00:07:50] Charlie: I find it fascinating, I have to say, bringing it back to, of course, being about me. I mean, I make my living with words, I’m a writer. I’m not a math guy. And you talked about that progression. Well, that progression for me ended with Algebra 2. But I have to say, what is very interesting to me is that I actually, I love numbers. In other words, I can do pretty much any numbers in my head. I am fascinated by them.

[00:08:21] Charlie: In fact, like when I’m working out or something and I need to sort of pass the time, I just do all these little numbers games in my head, what entertains me and everything. And I, it’s just interesting. I say that just because I wonder if I’m just not very typical for somebody who’s not really a math or a STEM person that I have this thing that I really enjoy arithmetic. Maybe there’s a lot of people out there like me, but the study you’re talking about really makes me think.

[00:08:45] Albert: Well, I ought to try your trick next time I’m running on the treadmill. Maybe that’ll help me get through some more hours.

[00:08:52] Charlie: Gets me through, gets me through that and I calculate batting averages and run averages. I don’t know if it works for me, but yeah.

[00:09:00] Albert: All right. Well, those are our news stories for this week and coming up after the break, we’re going to have Nina Rees, who’s the president and chief executive officer of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

[00:09:35] Albert: Nina Rees is president and chief executive officer of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Previously, Ms. Rees was Senior Vice President for Strategic Initiatives with Knowledge Universe. Rees worked for 15 years in Washington, D. C., most recently as the Assistant Deputy Secretary for Innovation and Improvement at the U. S. Department of Education. Reese also served as Domestic [00:10:00] Policy Advisor to the vice president of the United States. Nina, welcome to the show.

[00:10:05] Nina: Thank you so much for having me.

[00:10:06] Albert: So, let’s get you to reflect a little bit first. You’ve had a remarkably successful 11-year tenure leading the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. What are some of the policy gains and impacts that you’re most proud of?

[00:10:20] Nina: Well, that’s a great question. I would say for us at the national level, the increase in funding in the federal charter schools program is one of the highlights. The program was getting about $254 million in funding when I started. It’s now getting $440 million. And if the House appropriations plan for the CSP is enacted they will have added an additional $10 million. This is an important fact because this program offers seed funding for the growth of charter schools around the country. You’re a newcomer, you can get money from philanthropy. You can, if you’re connected with a CMO or EMO, you usually have funding, but if you’re not connected to any of those entities, which is really 65 percent of the sector, you don’t have any funding until you have enough students in seats. I’m extremely proud of this. This program is also open to CMOs who want to replicate and expand. It also offers funding to CDFIs and organizations that offer facilities finance. So, it’s been one of those powers and forces behind the scenes that’s fueled the growth of charter schools. And extremely proud of that.

[00:11:29] Nina: The second thing, of course, is the growth in the number of states that have charter school laws. When I came, we had about 40 or so states with laws. Washington State was the latest that had been added through an initiative process. And so, since then, we’ve added Alabama, Kentucky, Montana and West Virginia to the map. And we’ve also made fast improvements to several other laws by partnering either with someone on the ground or by going in doing the work ourselves in states like Wyoming, for instance, or Mississippi.

[00:11:59] Nina: [00:12:00] So, we do a lot of work behind the scenes and we don’t like to talk about it because ultimately our role is really just to jumpstart the movement and have others take over. But I should at this point acknowledge the great work that he has done in doing so. And then finally, of course, the past 11 years, have been kind of a lively set of years, three different presidents and a lot of discussion and turmoil, certainly around education issues, racial issues and whatnot. And, for me, just keeping my eye on the big picture and making sure that the brand of charter schools stayed out of some of these discussions was important and maintaining the bipartisan support for charter schools. I know there are a lot of discussions about that level, that bipartisan support in Congress remains in place.

[00:12:46] Albert: Yeah, yeah. We can get into that a little bit here. let’s talk about growth. So, as you know, over the past decade enrollment in charter schools has pretty much doubled we’re sitting at 3 to 4 million, I think, right now, and across almost 8,000 schools, really. So, you mentioned some states and what’s going on in some states but talk a bit more about that. What are some of the states that have had the largest growth, the ones that lag behind? And why do you think uh, some states’ enrollments really expanded in the charter sector for some states? And why performance has been better in some states than in others?

[00:13:19] Nina: Well, I have to be careful on how I answer this, since we’re all based in Massachusetts. So, the number is actually 3.7 million, which is a good, strong number, and it is continuing to grow. The states that have led the growth actually continue to be California, Texas, Florida, Arizona and that’s because they’re large and they have a lot of students in charter schools, but they also have policies in place — certainly in states like Texas, Florida and Arizona — that allow for charters to grow. With that said you can have growth, but are we going with quality and those questions that you’re addressing are really important because at the end of the day, the value proposition of charter schools, regardless of where you came from .is around offering something that’s much better than what we were getting before.

[00:14:06] Nina: And the data out of Stanford’s CREDO definitely demonstrates that it has done better over the time and become stronger by learning from its lessons and making improvements. And you know, in those places where it had hit firewalls, it is because of some policies, unfortunately in states like Massachusetts with caps in place, but in other places there are shifts in population, unfortunately, that are potentially reducing the number of people who are living in certain jurisdictions and impacting our growth. Or there is saturation in terms of the number of schools in a particular district. So how many more schools do you need? Parents may still want more options, but you’re going to hit a plateau of some sort. During the pandemic, I’ll just say, 240,000 families opted to send their children to charter schools. That is a huge number. 1.3 million families left the traditional public school system, but 240,000 remained in the public system by sending their children to charter schools. This tells me that if we had more charter school seats, more families would have opted for charter schools because they’re free, public and open to all.

[00:15:10] Albert: We’re certainly seeing some growth here in Arkansas elsewhere as well. So, so moving on from growth you mentioned just walking the politics of this. And so, I want to ask you to weigh in on this. From the beginning, charter schools have been controversial and mean, as you mentioned earlier, in recent years, it’s become a bit more complicated and contentious as the political landscape in D.C. and across the country has become more balkanized, if you will. Could you discuss where the right-left charter school coalition stands and what do you think needs to be done to help bridge political divisions around charters?

[00:15:47] Nina: Charter schools grew at the same time as a lot of other alignments around standards and accountability came together at the federal level and at the national level. So, charter schools and choice of whether they wanted to be included or not were always part of this larger discussion of standards, states’ accountability.

[00:16:07] Nina: And so, as you had those discussions and you had people come together from the left and the right to support those larger efforts. And use charter schools also as a mechanism for accountability. Of course, we grew and there was a lot of interest in what we did. And unfortunately, certainly at the national level, and unfortunately in some states as well, that whole standards-based accountability movement has — is no longer, you know — a solid coalition as it used to. That’s why there’s so much more attention now on charter schools as a reform in and of themselves. In every state where we have been able to make progress, we have had bipartisan support for charter schools. This is the case from the very beginning. Now, in some places, you might have more Republicans and Democrats. Like right here in Virginia, for instance, and people don’t talk about Virginia. I live in Virginia. And as there was a big discussion about opening more charter schools in Virginia. We had two senators, Democrats, who were supportive of charter schools. Unfortunately, one of them lost his election last year, but there’s always been alignment with Democrats, because they’ve seen this as a mechanism to offer choice within the public school system.

[00:17:17] Nina: And so, what you mentioned is the by-product of the parties fraying a little bit more and the media paying more attention to the voices on the far left and the far right. I personally don’t think the movement is going anywhere. And because so many of our constituents are people of color and are Democrats, now more than ever — and if you talk to Democrats for Education Reform they will agree with me on this — it’s really important for these constituents to make their voices heard, far more than ever before, to make sure Democrats certainly pay more attention to charter schools as a mechanism to keep our public education system alive.

[00:17:58] Albert: Well, you know O’m gonna ask one last [00:18:00] question here and then I’ll turn it over to Charlie. And you alluded to this earlier talking about the balance between quality and quantity. You’re aware of these debates. We want fast growth. On the other hand, we want to make sure students are well served. And one of the key mechanisms really trying to ensure this and balance this is our authorizers. And so, I’d like to ask, could you discuss the role that single and multiple authorizers play in charter policymaking for things like academic quality, diversity of pedagogy? And yeah, which states do you think do the best job at chartering different kinds of schools?

[00:18:36] Nina: So, authorizers extremely important because they’re ultimately the entities that hold schools accountable. So regardless of the quality of a state law, the person and the entity that’s ultimately going to make sure that a school is functioning well, that the entity that is attracting the best and the brightest to open charter schools and holding them accountable to both innovate, grow with quality — is going to be the authorizer.

[00:19:00] Nina: And those states like Massachusetts that have done well, have had strong authorizers. So, to your question of multiple authorizers, we always prefer having more than one authorizer. There are some exceptions to that rule. Right here in D.C. we only have one authorizer, but that’s because the district, which was also an authorizer, was doing such a poor job of authorizing that Congress, which oversees or the law in D.C. was created by Congress because D.C. is not a state. they were banned from authorizing. So, there are some exceptions in the case of D.C. and New Jersey, where you only have in the D.C.’s case, a district authorizer, and in New Jersey’s case, a statewide authorizer. And in both cases, they’ve done a decent job, but you never want to be beholden to just one entity.

[00:19:48] Nina: So, we want to have more than one authorizer and all things being equal it’s very important — and this latest study by Harvard demonstrates this — very important for the state education agency to be one of those authorizers. And in terms of quality, we also, I mean, this discussion of quality has always been so tightly knit with tests, which is important, but as our accountability systems have evolved and we have more information around and data around growth, these things all need to evolve so that we have a fuller picture of what a high quality school looks like and peg our expectations on that more so than just the raw test scores or snapshots of what’s happening in schools.

[00:20:35] Charlie: Well hi, Nina, thanks for joining us.

Nina: Thank you for having me.

Charlie: So, in recent years, you’ve seen massive federal K-12 education expenditures, after Race to the Top, ESSA, now COVID relief, ESSER, NAEP reading and math scores have declined and achievement gaps are largely unchanged or widening. You talked a little bit at the beginning about federal funding for charter schools, but could you talk about the strengths and weaknesses of federal K-12 spending and policymaking generally and where charter public schools fit in this national policy landscape?

[00:21:10] Nina: Well, federal funding for education in general is not that much. At most, it’s about 8 percent of total funding. Most of the funding for education is allocated at the state and local level. And for us as a sector, we’ve relied on a lot of the federal funding because, as our friends at University of Arkansas know very well, in many places we’re not getting our fair share of state and local funding, so programs like Title I and IDEA have been extremely important for our sector. So, we continue to be advocates of those programs, but I also would argue that the reason these programs are not functioning as efficiently as possible is because they’re often funneled into systems that are not very efficient.

[00:21:55] Nina: The solution, seems simplistic, but it is really for these funds to follow children to the schools of their choice. And once you do that and allow families to make those choices, you will see a difference because those entities that they’re selecting are likely going to make better use of the funds. And I know this is a complicated area and may warrant another podcast, but I still think the federal funds are important, but that they need to be connected more to the students in the system.

[00:22:25] Charlie: Right. Well, I think you touched on this a little bit before but in recent years, especially after the pandemic, two landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions on private school choice, and we’ve seen a lot of growth in ESAs, education tax credits, voucher systems. Can you talk a little bit about the relationship and the alliances and the tensions between public school choice like charters and private school choice, you know, those communities and the policymaking around them?

[00:22:56] Nina: I knew you would ask me these hard questions!

[00:23:00] Charlie: Well, that’s why you get the big bucks from us!

[00:23:03] Nina: These questions were questions that the charter sector was grappling with when it was first conceptualized. So, they’re not new. So as a parent — and any parent can attest to this — you just want to send your child to a great school. You’re not thinking about whether it’s public, private, religious and whatnot. You just want the best for your children. So as a parent, I believe in having more options, but as a parent and a taxpayer I also believe that there ought to be some accountability attached to the funding, and that’s why I’m a big supporter of charter schools — because they are accountable to a public entity while shielding the school from the politics that’s often connected to many of our public schools and the way they function.

[00:23:50] Nina: So, in states where essays are growing, my recommendation to the sector is, well, this is your opportunity to demonstrate your value, and if I had a choice between a great public charter school and another private school, I hope that the public charter school wins, so you can’t shy away from these types of efforts. People can always find resources, public or private, to send their children to a private school and new models are always going to emerge. So, my call to action to the sector is to pay attention to what’s happening and make sure that what we offer is better. And it has always been the case in many of those places where our innovations have emerged so that we don’t become like the very public schools that we set out to fix.

[00:24:39] Charlie: Yeah, I think that accountability to a public entity is an important distinction — that’s a very good point. OK, over the last decade or so, Diane Ravitch, teachers unions, have been very vocal about the role of private philanthropy and large foundations have played in K-12 education policy in charter schools. What’s been the impact of these pro-union arguments? you think these criticisms are valid? What level of responsibility does American philanthropy play in K-12 education’s ongoing struggles to deliver better results for kids?

[00:25:12] Nina: Well, look, philanthropy plays a role in so many different aspects of our life so it’s strange for — I mean, Diane and others can certainly say what they want — but you can’t stop, this is the way our country is set up. When you look at the level of engagement they have in the climate change discussion or other discussions. So, this student education is no different. I think the amount of money is actually not as much as what it could and should be in order to have a real impact.

[00:25:39] Nina: Most of philanthropy, philanthropists, you know, the best investors are those who allow you to take a degree of risk and have the stomach to live with that risk. And philanthropy is very conservative in many instances in around how it allocates funds and how much it can stomach that kind of risk-taking. So, so what I think what you’re asking is really private donations to different networks and those have been important because without it you wouldn’t have seen the emergence of a lot of organizations at the federal at the national level or at the state level to help support the growth of the sector. But philanthropy has also held them accountable. So, if they’re not producing results, a lot of the early organizations that were doing this work on the advocacy side have disappeared and new groups have emerged, which is a good thing. I think for the charter sector, though, because we now have about 8,000 schools and 3.7 million families, you also need to lean on those individuals who are going to these schools and benefiting from charter schools to subsidize and engage in the fundraising for the advocacy work a lot more. Because that’s how other advocacy groups have emerged and stayed in place.

[00:26:55] Nina: So, I’m not a fan of relying on philanthropy in perpetuity when you have so many people who are directly benefiting from an enterprise. As far as Diane Ravitch and other people’s concerns with funding going directly to schools, though, I’ll go back to the University of Arkansas study that demonstrates that inequality in funding that reaches a lot of charter schools around the country. In some states, the gap reaches about 60 cents of every dollar going to charter schools. So, so long as you have that gap, you can’t function a school effectively. You don’t have the competitive advantage to attract teachers and do your job well. So, you will always have to go fundraise for those seats in service to your families. And so, I wish the focus was really on outcomes more than funding. And I will also say that every penny that a philanthropist is spending on a charter school is money that’s going to public education and it should be celebrated.

[00:27:52] Charlie: Yeah. You bring up a good point there because we in Massachusetts have suffered a number of setbacks on charter schools in recent years, but I think it is easy for us to take for granted the fact that — I don’t think studies that we’ve done at Pioneer have shown that it’s not as if charter schools in Massachusetts get every penny that district schools do — but, I think they’re funded more fairly than a lot of other places, and I think it’s important to keep in mind that that is definitely not always the case. Certainly, as you know, better than I do, everywhere around the country.

[00:28:22] Nina: So, yes, the school is in the Northeast are very well funded and certainly the ones in Massachusetts. So, you are fortunate to have that dynamic.

[00:28:32] Charlie: Yes, yes.

[00:28:33] Nina: University of Arkansas and their latest study have demonstrated there are a lot of other schools that are still performing quite well without spending that much money. So, money alone is not the reason why success takes place. It is about the leadership of the school and how well that leader is able to both stretch their dollars, but also inspire their teachers in offering a high-quality education. Ultimately what happens in that classroom makes all the difference.

[00:29:03] Charlie: Yeah, and not just to make Professor Cheng feel good, but that was a very good study.

[00:29:07] Albert: Yeah, well, I was on one of them a long time ago, but I’ve been taking that mantle.

[00:29:15] Charlie: So, Nina, you mentioned, a while back, the new Paul Peterson, Denise Shaquille article in EdNext and full disclosure before you came on discussed a story that’s hot right now, and I just talked about that one. So, I’m curious to get your thoughts on the report, what you thought some of the major findings were and what its policy implications are?

[00:29:36] Nina: Well, as I’m sure Paul and his team can attest, it’s difficult to draw too many conclusions based on that report alone. The key finding that piqued my interest and one that is validated through the work we’ve done so far is the importance of a statewide authorizer. They found that charter schools that were authorized by a statewide authorizer tended to do better and that was connected to networks. These don’t surprise us based on what we’ve seen over the past 30 years and the fact that networks have been around a long time. They have learned from their mistakes and it’s. also validates work that Mackie Raymond at CREDO has done. I mean, since I’m leaving the National Alliance, my key takeaway was to go spend some time in Alaska. I was very surprised how well those schools were doing. I was sad that Hawaii was doing so poorly. I had spent a little bit of time in Hawaii and visited one of those schools, met with the governor who sends his own one of his kids to a charter school. And ironically — and I don’t mean to deviate too much — in Alaska, 99 percent of the legislature is Democratic and they all support charter schools. Our entire congressional delegation here in Washington is a supporter of federal funding for charter schools and charter schools as a concept. So anyway, so aside from those two kind of data points on their map, NAEP is a valuable tool. It tells you how the country is doing, how a sector is doing. And certainly, it’s important to pay attention to these things and disaggregate the data.

[00:31:10] Nina: But it’s just one of the data points out there. And I think in those instances where the sector hasn’t done well based on overall NAEP numbers, it is a call to action to increase attention to those markets and make sure that we are doing far better than we have in the past. But the fact is, right now, based on the data from Stanford’s CREDO, compared to nearby public schools, charter school students are doing better. But what this demonstrates is that on the NAEP, compared to overall averages and the overall, state charters are not as competitive as they should be. If there is any sector in the education space that’s ready, willing, and able to take a challenge, it is the charter school sector. So, I think this data will simply embolden and get more of our leaders to do better in the next go-round.

[00:32:06] Charlie: Yeah, it is a very interesting study. Very interesting study.

[00:32:11] Nina: And I think, you know, but look, I mean, Massachusetts in New York, these states that we knew have always done well performed well on this particular study. And then others, like Tennessee, which are — and right now in Tennessee, charter schools are mostly in two jurisdictions that are, mostly focused on closing the achievement gap — so I wasn’t surprised by some of the anomalies, but I think if you go to Tennessee, you have some extremely strong charter school networks that are doing tremendous work, both in closing the achievement gap, but also coming up with very innovative approaches to restorative justice. So, I don’t know. I mean, the thing with all charters in one category, as all of you know, you go to one charter school, you’ve really just seen that one school. They’re all so different from one another. So treating them as a monolith is also problematic to me.

[00:33:04] Charlie: Right. No, that is certainly true. That is certainly true. All right. So, although you seem very young compared to me, you’ve been working in public policy for several decades now and had high-level positions in government, nonprofits, in policy advocacy. When you look at this sort of landscape what would you like to see governors and state legislatures and local officials, parents do to really improve academic outcomes for America’s school children? Pretty broad question.

[00:33:32] Nina: Yeah. It’s, but it’s a great question. I believe governors when I started doing this work in the ‘90s, you had a lot of many governors who were called education governors. I know times have changed, and there are a lot of other issues out there that governors and leaders at all levels of government are busy with, but everyone can agree that education is at the core of a lot of our problems, whether it’s related to poverty, polarization, the American Dream, economic revitalization of a community. So, it’s sad that at the end of the day, some of these other more emerging and immediate issues or new issues end up taking up so much time. But to those who have seen this movie for several decades, they can all attest that if you fix their schools, these other problems will be easier to solve.

[00:34:24] Nina: But it takes a longer-term vision than one that most politicians want to have in order to double down on real investments in education. And again, charter schools are one of the more interesting and important pieces of the puzzle because they’re detached from a lot of the political turmoil that unfortunately hovers over our traditional public schools. And so, in that sense, if you want something that outlasts your tenure, paying a lot more attention to charter schools as the innovators that they are and as engines of social justice in many communities, and as an entity that employs a fair number of the people in the community. So, I would pay attention, I would, if I were running for public office. I would meet with these individuals try to learn from them and include them in broader strategies to revitalize my community, my state, also deal with this polarization issue that keeps getting worse, quite frankly.

[00:35:24] Charlie: Well, if you want to announce your candidacy here, we’re eady. No, that’s really well said. Thank you so much. And Nina, thank you not only for just for being here, but really for the great job you’ve done over the last 11 years. Those of us who care a lot about charter schools really appreciate it and really appreciate the good work you’ve done. So, thank you.

[00:35:45] Albert: Yeah, thank you, Nina.

[00:35:45] Nina: Yes, thank you for your leadership and support. I know I’ll be in touch with you, and hopefully we’ll get to see each other in person soon as well.

[00:35:54] Charlie: Sounds good. Thank you.

[00:36:30] Albert: That was a great interview, and last but not least, we have the Tweet of the Week, which comes from Barry Weiss. I don’t know if you’re in the loop with this Charlie, but she recently gave a lecture at the Federalist Society. I thought it was appropriate given that this week is Thanksgiving. I mean, she was offering commentary on what’s transpired over the last two months out in the Middle East and making arguments and exhorting us really to steward the blessings that we have from Western Civ, the things that have been bequeathed to us. We all know on thiis show that nothing’s perfect but I think she had a lot of insightful comments and things for us to ponder about what we might do to think how to preserve and steward the gifts that we’ve been bequeathed. And so, I think that’s an appropriate lecture to listen to particularly as we celebrate Thanksgiving and express some gratitude for all those who came before us, have given us and left with us.

[00:37:29] Charlie: Yeah, I have to say anything about Barbara Olson catches my eye simply because I just always remember, I just can’t forget in the days immediately, you know, Barbara Olson was killed on 9 11.

[00:37:42] Albert: Yeah, yeah. And I actually, we should clarify, I didn’t mention that this is the lecture in her honor, actually, in her memory.

[00:37:47] Charlie: Right. Exactly. Go ahead. I remember Ted Olson, who her husband, who I believe was the Solicitor General at the time, just coming on and being interviewed in the days after that. Poor guy was shattered, as you would imagine. And [00:38:00] it’s just always stuck with me. my attention is drawn to anything about that, just talking about learning to appreciate what you have, that’ll certainly do it for you.

[00:38:09] Albert: Yeah. So anyway, check out that lecture. There’s plenty of content there for some deep and good reflection. And so, with that we’re going to end our show for this week. Coming up next week, we’re going to have Dr. Kathleen O’Toole, who is the assistant provost for K-12 education at Hillsdale College. She leads really Hillsdale’s work in their K-12 office, founding and managing and really coming alongside and helping set up classical charter schools across the country. So, thank you, Charlie, for joining me this week on this episode.

[00:38:43] Charlie: Always a pleasure, Professor Cheng. Thank you.

[00:38:46] Albert: Join us next week, but until then, happy Thanksgiving, and we’ll see you next time.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Prof. Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas and Charlie Chieppo, interview the National Alliance’s Nina Rees. Rees discusses her 11-year tenure at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, highlighting policy gains, the growth of charter school enrollment, and the challenges of charter school politics. She explores debates on growth, quality, and authorizing of charters, and addresses the impact of federal K-12 spending and the evolving relationship between charter schools and private school choice. She concludes with insights on a new report ranking states’ charter school performance on NAEP and recommendations for improving academic outcomes in K-12 education.

Stories of the Week: Prof. Cheng discussed a story from The Hechinger Report on a survey of Alabama college professors showing a gap between high school math education and college expectations. Charlie addressed a story from Education Next exploring state rankings of charter school performance using NAEP scores from 2009-2019.

Guest:

Nina Rees is president and chief executive officer of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Previously, Ms. Rees was Senior Vice President for Strategic Initiatives with Knowledge Universe. She worked for over 15 years in Washington, D.C., most recently as the Assistant Deputy Secretary for Innovation and Improvement at the U.S. Department of Education. Rees also served as a domestic policy adviser to the vice president of the United States.

Nina Rees is president and chief executive officer of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Previously, Ms. Rees was Senior Vice President for Strategic Initiatives with Knowledge Universe. She worked for over 15 years in Washington, D.C., most recently as the Assistant Deputy Secretary for Innovation and Improvement at the U.S. Department of Education. Rees also served as a domestic policy adviser to the vice president of the United States.

Tweet of the Week:

You Are the Last Line of Defense.

This is the speech I gave in the memory of Barbara K. Olson @FedSoc. https://t.co/xzk8SvQkK6

— Bari Weiss (@bariweiss) November 13, 2023