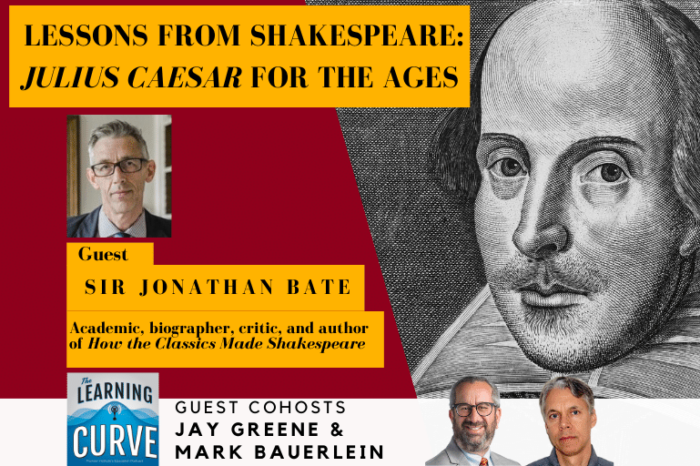

UK Oxford’s Sir Jonathan Bate on Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’

/in Education, Featured, Podcast /by Editorial StaffGuest

Professor Sir Jonathan Bate CBE FBA FRSL is Foundation Professor of Environmental Humanities College of Liberal Arts & College of Global Futures at Arizona State University. He is also Professor of English Literature in the University of Oxford and a Senior Research Fellow of Worcester College, Oxford, where he was Provost from 2011 to 2019. Well known as a biographer, critic, broadcaster, and scholar, he was also Gresham Professor of Rhetoric from 2017 to 2019, delivering six public lectures per year at Gresham College in the City of London. Sir Jonathan is the author of several acclaimed books, including How the Classics Made Shakespeare, (2019); Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, (2009); The Genius of Shakespeare, (1997); and Shakespeare and Ovid, (1994). He has served on the Board of the Royal Shakespeare Company, broadcast for the BBC, written for the Guardian, Times, Telegraph, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and TLS, and has held visiting posts at Yale, UCLA, and ASU. In 2006, he was awarded a CBE in the Queen’s 80th Birthday Honours for his services to higher education, and in January 2015 he became the youngest person ever to have been knighted for services to literary scholarship.

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a transcript here:

[00:00:00] Welcome to The Learning Curve. My name is Jay Greene. I’m senior research fellow at The Heritage Foundation, and I am again guest cohosting the Learning Curve. This time joined by my colleague, Mark Bauerlein.

[00:00:35] This is my third time guest hosting, so I’m beginning to feel like the Joan Rivers of the Learning Curve. That’s a reference for those of you old enough to understand it. But I assume that is our audience here. So, welcome again to The Learning Curve. I think we have a great show coming up featuring professor Sir Jonathan Beate to discuss Shakespeare’s play, Julius Caesar.

[00:00:56] But before we get to that, let’s first go through our stories of the week. My first story is easy for me to talk about because it’s something I wrote. This was a study that I did for the Heritage Foundation that was accompanied by an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal co-authored with my colleague and former student Ian Kingsbury about trends in school names.

[00:01:21] As it turns out there have been some significant changes in the kinds of names we give public schools over time. And we thought that this topic would be quite interesting because we think that the names we give schools says something about what it is that we value and who we wish to honor and why.

[00:01:42] I actually did a study along these lines back in 2007, and so this is in a sense, an update of that. And what we found is really two striking things. One is that schools named after presidents are in very steep, declining. And the biggest decline, by the way, is in schools named after Abraham Lincoln. There are almost 300 fewer schools named after Abraham Lincoln today than there were back in the mid-eighties. Also, several hundred fewer George Washingtons, FDRs—president names are disappearing now. Now, they’re not disappearing because schools are switching their names, they’re disappearing because old schools are closing that used to have president names and new schools are opening with other kinds of names, sort of like people named Mildred are disappearing not because people named Mildred are changing their name, but because older people named Mildred are dying off and newer people named Tiffany are being born.

[00:02:41] So, what are the new schools that are opening and what are they named if they’re not president names? So, we thought it might be kind of new ethnic civil rights heroes, and there is some increase in those names, but not very many. You’d be surprised, actually, there aren’t that many Malcolm X schools out there.

[00:02:58] There aren’t that many Cesar Chavez schools out there and not nearly enough to make up for the decline in Abraham Lincoln and George Washington schools. Instead, the big increase is in schools with vague nature names or aspirational names. So, they all sound a little bit like day spas or herbal teas or a little bit like motivational posters, so they’re Whispering Wind, Hawk’s Bluff, Excellence Institute, things like that.

[00:03:27] Now what does this all mean? I think it means in part that school boards are much less interested in patriotic names. That is, they’re less interested in conveying to our children s love of country as embodied by some heroic leaders of our country, including heroic leaders who are deeply flawed like all other humans.

[00:03:49] But this is not the result of a decline in patriotism in the country. That is, when we look at surveys about patriotism, Americans love their country about as much as they did in the eighties. So, this abandonment of patriotic school names is not friven by popular demand, it’s driven by school boards increasingly risk averse, and avoiding all possible conflict, perhaps in part because school board members now see themselves as in the farm leagues of politics.

[00:04:22] And they don’t want to destroy their budding careers. When in the past maybe school board members were more likely to be just kind of town elders who took turns helping run the town schools and weren’t so risk averse about naming schools after patriotic people, including patriotic people who had flaws and who had controversies that we might learn from by having schools named after them.

[00:04:46] So, that’s my story of the week based on the study that I did with Ian Kingsbury and the op-ed that we had about that study in the Wall Street Journal. Mark, please introduce yourself and tell us about your story of the week.

[00:05:00] v

Mark Bauerlein:

Very good. I, I didn’t know that about, school names. Very interesting, Jay. Mark Baurleim here. I’m an emeritus professor of English from Emory University, where I taught for 30 years. Retired a couple of years ago and also an editor at First Things Magazine and, for Pioneer audiences, I’ve done a lot of work with standards in English ELA standards, mostly for middle school and high school, especially in the last year.

[00:05:23] Interesting things are going on with ELA and some of the uh, actually more southern states. Anyway, here’s the news story that I have for you, Jay. You remember it wasn’t too long ago that the word among elite circles and actually not so elite circles, was that if you do not go to college, well, you must go to college or you’re gonna be a loser for the rest of your life.

[00:05:47] The numbers on, salaries, potential were out there. The George W. Bush and the Obama administrations both pushed that message and millennials took the message. They went to college in greater absolute numbers than any generation before. Well, the story here is that Gen Z. It doesn’t seem to have agreed, at least not at the rate that millennials did.

[00:06:10] I have here a story@abcnews.com with the headline, “Jaded with education, more Americans are skipping college,” and the central number here is this: In the last three years, 2019 to 2022, undergraduate enrollment nationwide dropped 8 percent. Now, given the size of undergraduate enrollment, that is a very steep decline. In many states where we used to have nearly 70% of high school graduates immediately going into some form of higher education, now, a lot of those states are now in the fifties percent rate. And the issue here is while there is a slight decline in Gen Z and simply numbers, Gen Z is a smaller cohort than millennials, the rate of decline suggests other reasons as well, and you can probably predict some of them. One, a lot of Gen Zers simply do not see a good strong match between what they learn in college and the world beyond college.

[00:07:22] Is this really going to help me get a better job? Are these tools that I learned in college really going to advance me? The second thing is, of course, cost. You know, do I really want to spend four years going into debt given the price of tuition these days and lose out on four years of full-time work? The cost benefit for them just doesn’t add up.

Next reason, the pandemic, the lockdown. Putting kids in a room, shutting down the schools, opening the screen—it actually had an effect of really alienating them from academic work. They weren’t as engaged in it. They didn’t learn as much and they knew that.

[00:08:07] The effect here, implied by the story, is that they really extended that to education as a whole. I’m here in my room. I’m doing my own thing. I’m on the computer. I don’t want to go spend four years going into rooms again with professors. I kind of like this freedom and this independence, and I want, again, I want to do my own thing.

[00:08:32] Now we see the options opening up in the pay, wages in manufacturing and retail service areas, which don’t require a college degree or any college course work. Those have climbed. I mean, look, look at what electricians, plumbers, welders—the employment outlook is pretty good for them. And so we see more youths going into apprenticeship types of education, not higher education, but for the trades. And I know Pioneer Institute has a study of vocational education happening that actually comes up with some very positive conclusions about that. And I’ll add to this, that those—the students profiled in the story—some of them are high achievers, they’re clearly, you know, high IQ types and they would’ve done well if they had gone to college. They’re not the marginals, it’s not only the marginal students who are turning away from the campus. A lot of solid performers are, too. And I think, Jay, you know, you and I, we left high school and going to college, it was a whole experience. It was going to be exciting. I’m getting out of the house, I’m going to be on my own. I can choose my own courses. I’ll make new friends. I can drink. I’m going to go to the basketball games, and I’m going to meet more girls, and it’s going to be a wonderful experience. That’s just not really the way a lot of Gen Zers look at college anymore, and I’m not sure why that is.

[00:10:02] I don’t know if it’s because, you know, or a lot of them turned off by the political correctness of the campus, is it just not a fun type of place anymore? Not sure, but it’s simply a college means something different now to a lot of Gen Z that it didn’t mean before. There we have it.

[00:10:22] And I think maybe the final thing the story doesn’t bring up is a lot of, especially liberal arts colleges, the smaller ones, a lot of them operate on the edge, they really need tuition dollars. And if they see, you know, a 10 percent drop, which might may only be, 40 or 50 students coming in, that could break them, we might see especially, in that we’ve got a little bit of a fertility drop from about 2008 forward, by 2025 ee actually may see a lot that decline in college numbers going down, and we may see a lot of the colleges closing shop.

[00:11:03]

Jay: Yeah, that’s actually a fascinating angle right there. They might also have to adapt how they offer. their education to actually be more in sync with what families and prospective employers might prefer. So you see this as mostly encouraging, not so much worrisome about kind of a dropout culture of people dropping out of mainstream society?

[00:11:28]

Mark: Well, I think a lot of young men in particular are dropping out of the sort of traditional achievement mode. A lot of them are turning off and I think it could be a bad thing. The story here highlighted those who are being more constructive about their lives; they simply don’t see college as providing them the kind of achievement and satisfaction that they really look for. They’re 19. And, I mean, maybe it’s, these are kids who’ve had their own social media brand for 15 years. They have been taught in so many schools, you know, take charge of your own learning, follow your passion, and now they’re doing it. They don’t see college as really the mode of fulfillment.

[00:12:15]

Jay: It sounds like a great opportunity to increase quality of vocational options so that the people who are disenchanted with this college path have better alternatives that are more productive and better suit their needs. And, also an opportunity for higher education in general to reconsider some of its past choices to be more competitive going forward, especially given declining birth rates as you note.

Mark: Anyone who’s had a problem go wrong with plumbing at your house knows we need more plumber.

Jay: Yeah. Yeah, it’s a good point.

Mark: And you can make—if you stay with plumbing for a few years, you know, it may be tough for the first few years, but boy, five years in as a plumber, you start moving up. Wages can be pretty darn good.

Jay: Thanks, Mark. That was an excellent story. And now we’ll be turning to our main event, which is to discuss Shakespeare’s play, Julius Caesar. With Professor Sir Jonathan Bate of Oxford University.

[00:13:34]

Jay: Welcome back to the Learning Curve. Professor Sir Jonathan Bate is Foundation, professor of Environmental Humanities, college of Liberal Arts and College of Global Futures at Arizona State University. He is also professor of English Literature in the University of Oxford and a senior research fellow at Worcester College Oxford, where he was Provost from 2011 to 2019. Well known as a biographer, critic, broadcaster. And. He was also Gresham Professor of Rhetoric from 2017 to 2019, delivering six public lectures per year at Gresham College in the city of London. Sir Jonathan is the author of several acclaimed books, including How the Classics Made Shakespeare, Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, The Genius of Shakespeare and Shakespeare and Ovid. He has served on the board of the Royal Shakespeare Company, broadcast for the BBC, written for The Guardian, Times, Telegraph, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and TLS, and he has held visiting posts at Yale, UCLA, and ASU. In 2006, he was awarded a C B E in the Queens’s 80th birthday honors for his services to higher education. And in January 2015, he became the youngest person ever to have been knighted for services to literary scholarship. Welcome to the Learning Curve, Sir Jonathan.

[00:14:55]

Sir Jonathan Bate: It’s great to be here. Thanks for inviting me.

[00:14:59] [00:15:00]

Jay: Today’s topic is Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. You’re regarded as one of the world’s foremost scholars on William Shakespeare, and we have the Ides of March approaching. So, maybe you could tell us something about what you think educators and students should remember about this play, think about this play, given that we have the timely Ides of March approaching.

[00:15:22]

Sir Jonathan Bate: Absolutely, beware the Ides of March, the warning of the soothsayer, the prophet to Julius Caesar as he approaches the capital.

[00:15:31] Julius Caesar, I think of all Shakespeare’s plays is the one that’s had most influence within American education, going right back to the 19th century. This is Shakespeare’s greatest political play, and at its heart are two great political themes. One is the danger of civil war and the other is the danger of dictatorship.

What we need to remember is that in many ways the whole Constitution of the United States is based on a Roman model. That idea of a mixed constitution where you have representatives of different parts of the community and a kind of balance of power between the legislature and the judiciary. That’s the Roman model. And of course, that’s why the great capital buildings in individual state capitals and above all, of course, the capital in Washington D.C.—they’re based architecturally on the Roman model. Julius Caesar is Shakespeare’s dramatization of the pivotal moment when the Republic of Rome comes to an end. Rome descends into civil war and then into an imperial system, a bit like a monarchy. So, the beginning of the play, Julius Caesar is offered the crown. The idea of instead of having power for a limited period, like an American president, the idea that he’s made perpetual dictator, essentially like an absolute monarch.

[00:17:10] The defenders of the Republic, Brutus, Cassius, their followers, they have to stop. And that leads to the assassination of Julius Caesar, probably the most famous assassination in world history prior to that of J.F. Kennedy. But then after the assassination, their faction falls apart, it falls into civil war, and then at the very end of the play, there’s a kind of anticipation of the moment when Octavius Caesar, the nephew of Julius becomes Augustus the first Roman emperor. So, this is the play about the dangers of internal political strife and the dangers of moving from democracy to absolutism for anybody coming up in America, that’s a crucial theme, isn’t it? Even today. Especially today!

Jay: Sure. So, we could connect the themes of this play to American politics today, to the American Constitution, but Shakespeare was writing before all of those things existed. And what do you think Shakespeare was saying about the Elizabethan situation in which he was working?

[00:18:20]

Jonathan Bate: Yeah, that’s a great question. This play belongs to 1599. It’s one of the few Shakespeare plays we can date with absolute precision. It was actually seen by a visiting tourist in London at that time. And this is towards the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

[00:18:39] And of course she has no children. So, there’s a real question about what is gonna happen when the old queen dies and there was a faction of people saying, well, maybe this is the moment for a big change. Maybe this is a moment where we should start thinking about a more democratic or even a republican form of government. Of course, it wasn’t for another 50 years that actually the republic emerged, when the king, King Charles I, was executed. But there’s a real debate about the balance of power between the aristocrats—there was not, of course universal suffrage at that time—the balance of power between the aristocrats and the monarchy. So, it’s a really hot topic. There’s this figure in the background of the Earl of Essex who at this time is out fighting against the Irish. And some people are saying, “Oh, well maybe when he comes back having conquered the Irish, it’ll be like Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon, that Essex will be the man.”

[00:19:33] Now, there’s no way that in a world where there is censorship of new plays, there’s no way Shakespeare could directly dramatize the controversies around forms of government in his own time. So, he does it indirectly through telling the Julius Caesar story through looking back to Ancient Rome.

[00:19:53]

Jay: Going back to Ancient Rome, you, you all in your book, How the Classics Made Shakespeare, you say that Shakespeare was the Cicero of his age. Could you talk about these classical influences on Shakespeare, including Cicero, Seneca, Plutarch? How does that Roman background influence Shakespeare? As you say, it also influences our own constitutional system of government in the United States.

[00:20:18]

Jonathan Bate:

Yeah. I mean the thing to remember about Shakespeare’s education was he went to a grammar school. He was fortunate to be born in an age when there were a lot of new grammar schools giving middle class boys—he was classic middle-class boy, his father’s a tradesmen and butcher—giving middle-class boys a free education.

[00:20:37] it’s called a grammar school because they spend all their time studying grammar. Not English grammar though, but Latin grammar. The whole basis of Shakespeare’s school education was the study of the classics. First, learning the basics of the Latin language. Then learning the arts of rhetoric, which we can talk about in a moment, and then beginning to read some of the great texts of ancient Rome.[00:21:00] The plays and the philosophy of Seneca, the great believer in the stoic philosophy of just firmly accepting all the things that life throws at you, and then maybe coming to a point where life is so bad, the noble thing to do is to commit suicide, which, of course, is what Brutus does at the end of Julius Caesar.

[00:21:19] But he’s also reading the poets such as Virgil and Horace and Ovid, but at the center of the reading was Cicero. Cicero was the greatest prose writer of ancient Rome. Really the arts of rhetoric, of persuasive political speech, these are learned from Cicero. And Cicero is actually a character in Julius Caesar, albeit he has a small part, but he is there among the conspirators, because Cicero was the great defender of the republic. This idea of the balance of powers. And then the other thing about Cicero is that he writes about the dangers of civil war. So, where I wrote in the book How the Classics Made Shakespeare, that Shakespeare was in many ways, the Cicero of his age, it was really for three reasons. One, his political intelligence, his astuteness as a political commentator, his ability to warn against the dangers of civil war, and then second, this idea of the power of rhetoric, the use of clever manipulative language to persuade your speakers. Cicero did it in a political arena, Shakespeare in a theatrical one. And then, the third thing is a more specific thing that one of Cicero’s key ideas was the importance of friendship and of loyalty. His most influential work, which Shakespeare knew well, was about how society can only really operate through a system of mutual benefits.

[00:22:54] People looking after each other’s interests, doing favors for each other, that creating a sense of a bond. And what Shakespeare explores in the second half of Julius Caesar is the breaking down of that bond of friendship between Brutus and Cassius. And so, in Julius Caesar, all those kind of three aspects of Cicero—the fear of civil war, the breaking of bonds of friendship, and above all the power of rhetoric—those are all embodied in the play.

[00:23:22]

Mark Bauerlein: Professor Bate, you know on what you said about Julius Caesar so important to American education. I would say that the memorization of “Friends, Romans, countrymen…” that might be the most, memorized exercise in the history of, of at least 20th century American education. And you’ve got these two funeral orations by Marcus Brutus, and Mark Antony. What are the rhetorical features of those contrasting speeches and what, kind of contest should students take from that?

[00:23:55]

Jonathan Bate: Yeah, it’s a great question. And Shakespeare’s just so damn clever, so smart in the structure of the scenes he puts together. What’s happening here is that the two sides, Brutus, defending the assassination of Caesar on the grounds of it’s needed to save the republic and stop a monarchy. And then Mark Antony attacking the conspirators. They’ve got to persuade the plebeians, the ordinary people. Brutus goes in first and he thinks I need to use prose, relatively understandable, not too fancy language. It’s always this convention in Shakespeare that the upper-class characters speak verse and the lower-class characters speak prose. So, Brutus thinks he’ll kind of get down with the people by speaking prose, but it is nevertheless a very rhetorical speech in the sense of having these kind of formal symmetries in the speech.

[00:24:46] It begins: “Romans, countrymen, and lovers hear me for my cause and be silent that you may hear…” That way of beginning and ending a sentence with the same phrase. Hear me that you may hear. Believe me, for my honor, have respect, my honor that you may believe again, the sentence beginning believe and ending believe. And then he goes on about living and dead. Dead and living. So, this sort of sense of really making his speech accessible through the use of repetition, and that seems to be pretty persuasive. It’s a simple form of rhetoric, essentially involving drumming the idea in through repetition.

[00:25:31] But when it comes to Mark Antony, he does something much more sophisticated. He begins with a similar threefold formulation, as you say, the one that for maybe 200 years American schoolchildren used to learn. “Friends, Romans countrymen, lend me your ears…” Immediately there you’ve got a form of metaphor, I mean the device there is known as synecdoche, substituting the part for the whole. He doesn’t mean literally cut off your ears and then—he means listen to me, but he’s doing it in a way immediately, it’s like poetry. It’s an evocative image, the idea of the lending of the ears.

[00:26:09] And then he uses this device of irony. He goes on and on about Brutus being an honorable man, but the more that he repeats it and suggests the contradiction between what Brutus says and what he’s done, that leads the plebeians to begin to say, yeah, actually, maybe Brutus is not so honorable.

[00:26:30] And then he makes the crucial move of going from simply argument, simply using reason, into a rhetoric of emotion. If you have tears, prepare to shed them now. And then a lot of language about weeping. And then he physically shows the body of Caesar. So, he’s not just using words, but he’s linking words to actions. And he’s creating emotion. So, although Brutus has kind of logic on his side, what Antony has is this particularly forceful form of rhetoric that begins with words, but then moves to feelings. And, ultimately, it’s the emotions that override and as a result of that, he kind of wins the debate.

Mark: A lesson for all leaders, right?

Jonathan Bate: Absolutely.

Mark: Um, we have two other characters. Calpurnia and Portia, Caesar’s and Brutus’, respectively, wives. They’re very strong, perceptive figures. What perspective on the events leading up to the odds of marching assassination itself, do they provide, is there a distinct angle that they offer?

[00:27:43]

Jonathan Bate: Very much so. I mean, in, in some ways Julius Caesar is one of Shakespeare’s least rewarding plays for female actors and female readers. You know, it doesn’t have the great female parts like Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra. Or the great comic parts like Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing or Viola in Twelfth Night.

[00:28:05] It doesn’t have a really powerful woman like Lady Macbeth. They’re pretty small parts, the two wives. But Shakespeare there is just being honest in reflecting the patriarchal nature of Roman society where women had no public role whatsoever. So, when we see Portia, the wife of Brutus, Calpurnia, the wife of Caesar, we only see them in a domestic setting. We only see them briefly, but even within those brief scenes, they are characters of great wisdom in different ways. Portia is the daughter of a famous defender of the republic, Cato. And she has both a kind of political wisdom, but also great tenderness as a wife. She sees how Brutus is torturing himself about whether or not she should join the conspiracy.

[00:28:55] And she says, I’m your wife. I can advise you. I can help you. Listen. Listen to me. Listen to me. But Brutus is reluctant. She says, I’ll keep your confidences. The wife of Caesar, she in a way is, perhaps a less emotionally mature figure. But then, you know, she’s an army wife. You know, Caesar’s been off fighting wars, fighting wars against the Gauls and conquering Britain. And then fighting the civil war against Pompey which is the pre-action of the play. So, Coper know, she’s had to get used to the risk of her husband being killed in combat, but she’s got a really strong instinct that something’s going to go wrong on the Ides of March.

[00:29:36] Julius Caesar doesn’t listen to the soothsayer saying, beware the Ides of March. He does listen to Calpurnia. She’s right. But then some of the others come in and he changes his mind and his, kind of military pride overtakes his husbandly loyalty. So they are, yeah, they are, as I say, small but really interesting parts. And in way Shakespeare is saying, as he says, in so many of his plays, especially his comedies as opposed to his tragedies, women are often the wiser ones for smarter ones than these impulsive men.

Mark: Yeah. Last question. In a way, Brutus gets the final word, although it’s not spoken, it’s spoken about him: “this was the noblest Roman of them all. His life was gentle in the elements, so mixed in him that nature might stand up and say to all the world, this was a man.” What are we to think? I mean, this is, this is ambiguous, right? What are we to think about Brutus joining with the conspiracy and using the knife. where should we come down on Brutus?

[00:30:34]

Jonathan Bate: Yeah, absolutely. It’s the great question, isn’t it? I mean, you know, Caesar’s words as Brutus puts the knife in, again, among the most quoted words in Shakespeare, “Et tu, Brute?” Every time there’s a political betrayal, that those are the words that come into the mind of the person who thinks they’re being betrayed.

But in the end, Brutus decision is that maintaining the republic, let us say maintaining the democracy, is more important than his personal loyalty to Caesar. He feels he has to do it. If one wants to be sort of vulgar and contemporary, it’s the Mike Pence moment, isn’t it? The moment in which he weighs his duty to the republic against his loyalty to the friend and leader. But then what Brutus discovers is that as a result of the conspiracy, the world of Rome has descended into civil war. That’s what second half of the play shows with all those battles and things. And he, at that point, he realizes, have I actually saved the republic? We’ve ended up fighting each other. Octavius is going to come through and effectively he’s going to become an emperor, a monarch. In some sense, it was all for nothing. And so therefore, I’m going to do the Stoic thing and take my own life. And the nobility is in the recognition that he was given this kind of impossible choice. He made what he thought was the right choice, but then it all unraveled and went wrong. And then the noble thing was to say, “Hey, I’ve screwed up. All I can do is take my own life.” And there is a kind of nobility about that.

[00:32:11]

Jay: Sir Jonathan, if I could have one last question before we run out of time. Just to bring us back to the political message which you hinted at here, in Brutus, realizing ultimately the futility of his efforts to stop a dictatorship. Do you see in this play a warning to reformers to not reform because it backfires or is undone?

Jonathan Bate: Yeah, I absolutely do. No, that, I think that’s absolutely right, and this of comes back into my mind of the things that are kind of brewing in the circle of the Earl of Essex and, Shakespeare knew that circle pretty well. The Earl of Essex’s right-hand man was the Earl of Southampton, who was the patron of Shakespeare. Shakespeare dedicated poems to Southampton, one of which is a poem called The Rape of Lucrece, which is also about this whole question of imperialism versus republicanism. But I think what Shakespeare is saying is whenever you get an overthrow of a powerful figure, a singular, absolute ruler, civil war is likely to follow. He’s explored this already in all his English history plays, his plays about the English civil wars, the so-called Wars of the Roses. So, it’s this balancing act, that on the one hand you don’t want a tyrant, which is what Richard III is, but then, on the other hand, if you overthrow the leader, if you assassinate the leader, then you are bound to descend into the chaos of civil war. And it is that, as I say, that fear of civil war that I think is so crucial.

[00:33:49]

Jay: There’s something kind of small-c conservative about this. I think there is warning against radical change. It’s funny, I had a—the professor who helped teach me to love Shakespeare was Linda Bamber at Tufts University who some of the listeners might know. she always argued that Shakespeare’s comedies were, fundamentally conservative because the world was restored to how it should be at the end. But maybe in the tragedies we see something fundamentally conservative as well.

[00:34:18]

Jonathan Bate: Yeah. And I think, his earlier tragedy Titus Andronicus, which is set in a kind of fictional ancient room is, a really good example of, again, this sort of, the problem of, on the one hand, you don’t want a tyrant on the other hand civil war causes absolute chaos. And what happens at the end of that play? There’s a lovely image the young man’s character called Lucius who comes to power and he speaks of knitting together the state into one mutual chief, the idea what we need to do is avoid extremism on both sides but bring the community together in a form of unity. But it would be a form of unity that, does involve a strong element of submission to power. Once you have a kind of free for all, then you get incidents like the moment in Julius Caesar where the crowd, having been riled up by Mark Antony, just like, right, we’re going to kill one of the conspirators. “Oh, there’s a chap called Cinna. Cinna, he was one of the conspirators. So, they tear this guy to pieces. Oh, right, right. It’s not Cinna the conspirator, it’s Cinna the poet, who in some sense stands in for Shakespeare. Shakespeare saying, hang on, if we have a revolution, the first person to be torn apart is going to be me!

[00:35:32]

Jay: Right. Well, is there a passage that you would like to close this discussion with that by reading that, that might be useful for our audience to hear?

Jonathan Bate: Yeah, I mean, I think this picks up very well this, as I say this, this danger of the internal division in a state, because it’s something that Shakespeare covers, right across his works. So, I’m just going to read a paragraph from my book How the Classics Made Shakespeare, showing how that theme occurs in both his English history plays and his Roman history plays:

“Shakespeare’s history plays, both ancient and modern, are all marked with Cicero’s idea of the peculiarly heinous nature of civil war. It was Cicero who actually invented the term civil war. In Shakespeare’s Roman world, there are the civil wars of Titus Andronicus and Julius Caesar. “Domestic fury and fierce civil strife shall cumber all the parts of Italy.” In his English histories, civil strife is the linking theme. Richard II introduces it: “The dire aspect of civil wounds plowed up with neighbor’s sword. The two parts of Henry IV act out “the intestine shock and furious clothes of civil butchery in a poor kingdom sick with civil blows.” Henry V temporarily suspends it by means of foreign war, but the shadow is always there, as the king recognizes: “Now, through my father’s ambition, he was thinking of civil wars when he got me.” In Henry VI, civil war is back. Part I: “Civil dissension is a viperous worm that gnaws the bowels of the Commonwealth.” Part II: “He thinks already in this civil broil, I see them lauding it in London streets.” Part III: “Conditionally, that here thou take an oath to cease this civil war.” But it only does cease with Henry Tudor’s victory at the end of Richard III: “Now civil wounds are stopped. Peace lives again.” And it seems to me in our time of, to use Shakespeare’s phrase, civil dissension, this is an extraordinarily contemporary message, even as it takes us back to 1599 and from there, back to Ancient Rome and the Ides of March.

[00:38:06] Jay: Well, thanks so much for being on The Learning Curve. This has been a fantastic discussion, and I think it should help all of our listeners, including educators and students, think about the continuity of history and of these works of art in helping us understand situations that recur including, as you say, moments of civil strife. So, thank you so much for, offering these.

Jonathan Bate: Thank you, it was a pleasure to talk to you.

[00:38:58]

Jay: So the tweet I’d like to discuss this week is actually something from The Wall Street Journal where they had an op-ed about a piece that, said that college classes taught in prison were actually models for how we might wish to see college classes taught on college campuses, that prisoners actually can be quite good students and quite focused on learning in a way that we don’t often see on college campuses. And for those of you who are interested in learning more about the lessons that might be learned from college courses taught in prison, there’s an excellent documentary called College Behind Bars, which is about the Bard Prison Initiative. So, Bard College actually has been running a very high-quality program of offering college courses in prisons in the state of New York. And this documentary features some of the prisoners, some of the content of those courses. And I found it very inspirational, actually. It really can make you think about how maybe education that is sometimes wasted on people who don’t really want it.

[00:40:10] And that the people who want education the most are the ones who can benefit from it the most. And they come in, all walks of life from all places, and they’re in prisons, too. And I think we can all be inspired by learning more about that. So that’s my tweet of the week from this Wall Street Journal opinion, called “College should be more like prison.” Well, it was great hosting this again and great co-hosting with you, Mark. Thanks for joining me here and next week Cara and Gerard will be back in their regular spots where they will be joined by their guest professor, Dan Willingham. So, tune in next week for The Learning Curve.