Pioneer Institute Study Finds Wide Range of Approaches to Compliance with MBTA Communities Law

Lexington’s approach seen as a model

BOSTON – As Massachusetts’ Supreme Judicial Court prepares to hear a challenge by the Town of Milton to the enforceability of the MBTA Communities Act, a new Pioneer Institute study finds that the 177 municipalities covered by the law are taking a wide range of approaches to implementing it.

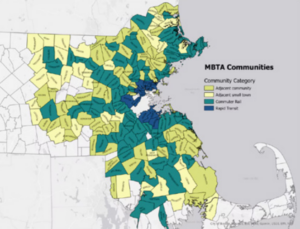

The Act, enacted in 2021, requires that 177 communities create at least one reasonably sized district within half-a-mile of a transit station where multi-family at a gross density of at least 15 units per acre is permitted as of right. All these communities are deemed to benefit from access to public rail transit, either because they have a station in their municipality or nearby.

The law gives the state power to withhold grant money from municipalities that fail to comply. Governor Maura Healey and Attorney General Andrea Campbell have said they will go as far as needed to force all 177 communities to obey the law.

“Several communities are waiting on the outcome of Milton’s challenge before deciding how or whether to comply,” said Andrew Mikula, the author of “The MBTA Communities Act Three Years Later: How Massachusetts Municipalities Are Implementing (or Resisting) Multi-family Zoning.” “Many have concentrated the districts in areas with existing commercial or multi-family housing facilities, and a couple have gone much further than the law requires.”

In February of this year, Milton voters rejected the town’s MBTA Communities Act compliance plan by a 54-46 percent margin.

Mikula finds that the law takes a middle ground approach regarding local control of planning and zoning, mandating that local officials create multi-family housing districts by right, but allowing them to choose how and where to do it. State housing/zoning policies without this mandatory component have been less successful as a catalyst for housing development.

Specific requirements and deadlines for communities to comply with the law depend on how it is classified. For example, a municipality with a rail transit station is generally required to permit more multi-family units and do so more quickly than an “Adjacent Community” that benefits less from transit access. Final compliance deadlines range from 2023 to 2025.

Housing experts and local officials estimate that only a small percentage of the new capacity permitted under the law will be built in the first few years of implementation.

“This is a long-term approach and it won’t on its own solve the Commonwealth’s housing shortage and our affordability problems,” said Pioneer Executive Director Jim Stergios. “But it could reduce upward pressure on housing costs by expanding supply.”

Opposition to the law is sometimes based on concerns that multi-family housing development results in higher costs in areas such as schools and emergency services, but several studies have concluded that additional property taxes and other new revenues are usually enough to pay for the extra costs.

Among Mikula’s recommendations are that, when possible, communities should build upon existing work on transit-oriented development and/or planning for multi-family housing when developing compliance plans, they should engage in meaningful community outreach and engagement early and often, and they should involve a broad group of stakeholders in the compliance process. Specifically, that should include those who own businesses and property in the municipality in addition to residents. He cites Lexington’s process as a model for compliance.

“In October of 2022, Lexington began a process that built on the comprehensive plan the town had adopted a month earlier and included meaningful community outreach to a wide range of stakeholders,” Mikula said. “Today, over 600 of the 1,600 new housing units proposed in new MBTA Communities districts statewide are in Lexington.”