Cap, Talent Pipeline, And Facilities Funding Among Factors Prohibiting State Charter Sector From Achieving Scale

“Yes” vote on statewide ballot initiative could attract more quality charter management organizations

BOSTON – Raising the cap, strengthening teacher and school leader pipelines, and revising facilities funding are among the key factors if Massachusetts is to succeed at bringing its charter school sector to scale, according to a new study published by Pioneer Institute.

“Gold-standard research demonstrates that Massachusetts charter public schools are among the nation’s best,” said Dr. Cara Stillings Candal, author of “Massachusetts Charter Public Schools: Best Practices in School Expansion and Replication.” “But many of these high-performing charters are small ‘boutique’ schools.”

Uncommon Schools, KIPP, and SABIS are the only charter networks operating in Massachusetts that are also present in other states.

While it’s not unusual to see some individual schools struggle, research shows that charter management organizations (CMOs) have continued to produce better results than local school districts as they achieve scale.

The biggest reason there are so few CMOs operating in Massachusetts is the existing charter school cap, which prevents the organizations from achieving scale. The percentage of school spending that could go to charter schools was doubled in low-performing school districts in 2010, but some districts were already approaching the new cap by 2013. Demand was so great that the state imposed a moratorium on new charter applications during the 2011-12 cycle.

The 2010 cap lift also excluded new CMOs because any additional charter seats were available only to “proven providers” that were already operating at least one successful charter school.

This dynamic could change if voters approve a statewide ballot initiative in November that would allow up to 12 new charter schools to open each year in low-performing districts.

In addition to the cap, Massachusetts is a small state with fewer students than states like California and Texas in which CMOs are more active. There is also little incentive to expand beyond urban areas here because other public schools generally perform well.

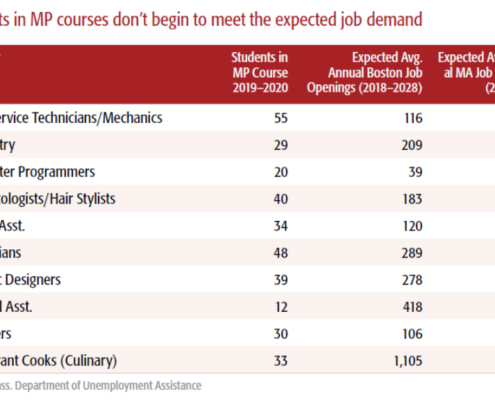

The availability of high-quality teachers and school leaders can also be a key constraint for CMOs looking to expand. While Massachusetts has a wealth of colleges and universities, many of which have strong teacher preparation programs, it also has shortcomings.

There is a lack of diversity among those working in schools. A 2014 Boston Globe review found that Massachusetts school staffs were 92 percent white. There are also educator pipeline problems in the commonwealth’s largest districts, which tend to have high rates of poverty.

And while Massachusetts generally has an equitable charter school funding system, that doesn’t extend to capital money. Unlike traditional public schools, charters have no access to the local municipal tax base or to funds from the Massachusetts School Building Authority. Instead, they receive only a small per-pupil stipend for facilities.

About the Author: Cara Stillings Candal is an education researcher and writer. She is a senior consultant for research and curriculum at the National Academy of Advanced Teacher Education and a senior fellow at Pioneer Institute. She was formerly research assistant professor and lecturer at the Boston University School of Education. Candal holds a B.A. in English literature from Indiana University at Bloomington, an M.A. in social science from the University of Chicago, and a doctorate in education policy from Boston University.

###

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.