Commuter Parking Woes Highlight the MBTA’s Problem With Planning

Almost a decade after the completion of the Big Dig, the project aimed at solving significant transportation needs has become a legendary case study of mismanagement. What do we have to show for it?

The tendrils of the megaproject continue to tie knots around the state’s infrastructure decisions. Some of the transit projects that the Conservation Law Foundation negotiated with the state back in 1990 are still underway, including, for example, the long-awaited Green Line expansion to Tufts University in Medford.

The principal components of the Big Dig project—the three highway tunnels, new river crossing, rail expansions and other features—are completed, but have the expected results been realized?

While downtown is no longer subject to the rumblings of the elevated highway system and traffic has indeed been removed from the public eye and streamlined, Boston still remains among the worst cities in the country for commuting according to the Inrix Traffic Scorecard.

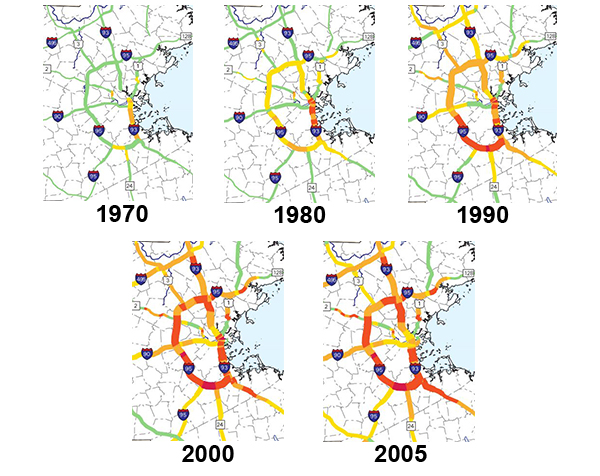

Figure 1. Traffic Volumes in Boston’s Surrounding Region

(Images taken from Boston Regional Metropolitan Planning Organization’s website (MPO). Yellow roads are 75-99% filled to capacity, the darkest red represents volumes 150% of the road’s practical capacity.)

As Figure 1 demonstrates, the rise of congestion in the Greater Boston area may have been slowed by the Big Dig, but it has not been reversed. The sea of traffic now completely engulfs the I-95 ring, and threatens to do the same to I-495, affecting more than a hundred of the Bay State’s most densely populated towns and cities. Additionally, while the average large American city reduced traffic waiting time by 12.8 percent since 2006, Boston’s has increased. Remember, the Big Dig completed construction in 2007.

If the Big Dig has failed to live up to its lofty expectations of reduced congestion, why is it that Massachusetts has not seen an increase in transit usage as the work force continued to grow? As Pioneer has demonstrated previously, unlike other top American commuter rail systems, the MBTA’s commuter rail ridership declined by over 10 percent between 2003 and 2013.

While declining ridership is a big issue for the MBTA, the problem has been compounded by this winter’s storms that caused a drop in MBTA service matched only by the public’s loss of confidence in the Authority.

The talk of the town for the last two months has been the MBTA’s seemingly hopeless situation, trapped between mountains of debt and deferred maintenance projects. The commuter rail system has still yet to bring back full service even though the last major snow storm took place a month ago.

To pull itself out of a decline in commuter rail ridership, the T will need to retain its current customer base and find ways to attract more. The most reasonable priority for the Authority is to maximize ridership potential within the current system’s existing service area.

Nicole Dungca’s March 23rd piece in the Boston Globe underscores the parking crisis closer to the Hub. Red Line stations like Braintree frequently experience 99 percent parking utilization rates, causing many to drive into the city instead. There are clearly some constraints on access to parking that are leading potential riders to turn to their cars.

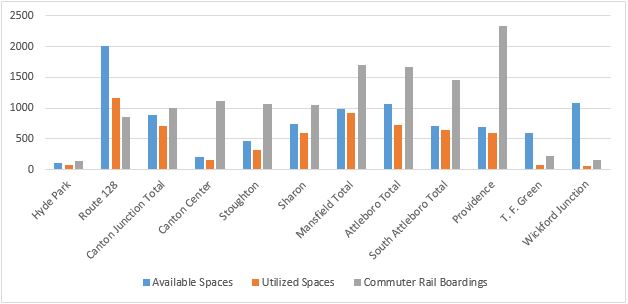

An analysis of the Boston MPO’s parking data for commuter rail stations in 2013 shows that terminal stations often fail to attract the expected number of riders. Figure 2 shows that the two furthest stations on the Providence/Stoughton line, T.F. Green and Wickford Junction, both have far more spaces available than they have commuter rail passengers.

Additionally, 25 percent of the spaces at Greenbush Station were used during the morning commute, 23 percent at Fitchburg Station, and 9 percent at Plymouth Station. None of these terminal stations has especially large parking facilities when compared to the rest of the commuter rail system.

Figure 2. Parking and Ridership Levels, Providence/Stoughton Line, Morning Commute

Terminal stations are frequently constructed with an anticipation of large ridership. Greenbush Station’s facility has almost 1,000 spots, while Wickford Junction on the Providence line has room for 1,077 spots, 61 of which were actually used. T. F. Green Airport, the second to last stop on the Providence line, has spaces for 591 cars, 70 of which were used.

Other commuter rail lines, specifically the Framingham/Worcester, Franklin, and Lowell lines, are reaching their parking capacity limits. Every stop on the Lowell line experienced more than 50 percent parking utilization, while almost half of the Framingham/Worcester stations had utilization levels greater than 75 percent. Figure 3 shows that the Worcester line has high ridership levels despite many stations approaching full utilization.

In total there were 7 stations on all lines which had no available parking spaces, and there were 10 others that had utilization rates of 90 percent or higher. It’s clear that at some stations a lack of parking is a hurdle to increasing ridership.

Figure 3. Parking and Ridership Levels, Framingham/Worcester Line, Morning Commute

Whether it’s a flaw of design or execution, the MBTA is not tapping into the greater potential ridership that both mid-line and terminal stations can offer. Answers and improvements in this area could spur the positive ridership growth that the MBTA has been missing, while also taking drivers off the roads.

The terminal stations offer a lesson to MBTA planners. More spots isn’t always the right answer, it’s more important to have an intelligent and need-based distribution of parking. Just as the Big Dig helped to mitigate but did not reverse congestion, smart parking plans can help to lock in the commuter rail’s leaking ridership before the problem escalates.

The MBTA’s commuter rail services are critical to Boston and the region. More than a hundred thousand people rely on commuter trains to access the city each day, a task it is barely managing at the moment. If there was a lesson from the MBTA that we all should learn, especially from the unthoughtful way in which the state committed to numerous transit expansions in order to move the Big Dig project ahead, it is that intelligent planning (including a business planning mindset) is important when you are providing services to people.

The threat of congestion in Boston has been mitigated by the Big Dig, but it is creeping up once again. Addressing parking needs throughout the region in order to facilitate use of public transportation offers some hope. If the MBTA fails to act then the rising tide of traffic may turn our freeways into parking lots.

Scott Haller is a student at Northeastern University working at Pioneer Institute through the Co-op Program.