Can Massachusetts Reverse the Decline in U.S. History and Civics Performance?

A standardized test for high schoolers should accompany the Bay State’s best-in-class standards

Amidst the enduring fallout from pandemic-induced school closures and remote learning, many parents and education advocates saw their worst fears realized in the June release of National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results, commonly called the “nation’s report card.”

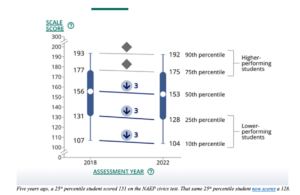

The national assessment for American eighth graders revealed record lows in students’ history and civics performance since testing began some 30 years ago. Barely 20 percent of 2022 eighth graders register “proficient” on examinations measuring their understanding of the U.S. Electoral College system or how the political process is used by citizens to influence government. Even fewer students are taught by teachers with relevant subject expertise. And the knowledge gaps between low-performing students and their high-achieving counterparts skew wider than ever.

Results from the NAEP’s U.S. history exam tell a similar story. Eighth-grade performance declining nationally in 2022 is troubling in itself. But given that the decline follows poor performance in both 2018 and 2014, the problem clearly extends far beyond any pandemic-related learning disruption. Students across the country have been shortchanged on historical and civic education for a decade, if not longer.

The fact that 25th-percentile students in 2022 perform similarly to 10th-percentile students in 2014 suggests the problem lies with degraded instruction and serious curricular holes in history and social studies classrooms across the country. Without study of the Founding era, the Constitution, and its legacy in our twenty-first century republic, the next generation of voters and taxpayers will be ill-equipped to exercise the duties and privileges of their citizenship.

On the surface, Massachusetts — home to so much history, including seminal events such as the Boston Tea Party — has much to be proud of in its own students’ history and civics performance. It is one of three states, along with Washington, D.C., with “exemplary” curricular standards across middle and high school education, according to the Fordham Institute’s 2021 nationwide canvassing of individual state requirements.

Even as policymakers have supplanted typical curricular standards with “engagement” mandates that students participate in progressive activism, and added what Pioneer in 2018 called “unreadable… jargon” to course guidelines for teachers, national attitudes towards Massachusetts’ civic education have remained envious.

Unfortunately, parents have long been left in the dark as to how the decline in national performance is reflected within the state. In February of 2009, against the pleas of civic education advocates and parent groups, the state postponed a proposed MCAS test in high school civics following years of design and piloting. What was introduced as a “temporary postponement” became a decade-long suspension of civic educational accountability, as the legislature ignored countless calls to reconsider administering the exam and setting a benchmark for Bay Staters’ performance.

Without a standardized measure of civic and historical aptitude completed at the end of one’s high school studies, parents have no way of knowing whether their child’s curriculum truly is “exemplary” compared to other states.

Since the February 2009 postponement, attempts at restoring the state’s confusing 2018 pilot program for social sciences — which included plans for a standardized civics exam but nothing for a formal history exam — were approved with no clear timetable for actually testing students on the newly-degraded history and civics standards, confusing parents and educators alike.

The state also used the COVID-19 pandemic to suspend MCAS testing for all subjects, entertained calls to continue the suspension long after the public health crisis peaked, and has even weighed legislation that would abolish standardized testing indefinitely.

These troubling developments come as recent Pioneer/Emerson College polling finds 62 percent of Massachusetts residents support the return of history and civics exams in high schools across the Bay State, highlighting the extent to which education policymakers are out-of-step with the majority of citizens, whose education and whose children’s education they administer.

To fulfill the original charge of our nation’s public schooling system — instilling a “common” political and social philosophy across ethnic and class divides — history and civics education must be refocused around ensuring baseline knowledge of our republic and its institutions. Students deserve better than what they’re getting: confusing and non-rigorous academic standards, teachers with limited expertise, and overly politicized curricula.

Restoring assessments in history and civics will level the playing field and set academic standards in keeping with Massachusetts’ record of educational achievement.

Jude Iredell is the Roger Perry Civics Intern with Pioneer Institute.