Better Civics Education Is the Massachusetts Way

Override of governor’s civics budget cut a sign of hope

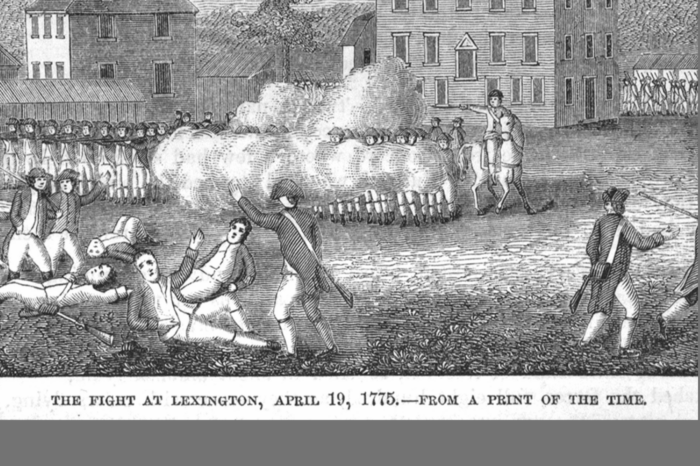

Massachusetts is arguably the most educated state in America, and one of the birthplaces of America’s civic tradition. If there’s any place in the country where you would expect to find consensus about the value of teaching American history, it is here.

Unfortunately, the fight for more comprehensive civics education in the Bay State has persisted for years with no sign of abating. Advocates won an important battle recently when public outcry led the Legislature to override Gov. Maura Healey’s cut to the state’s modest civics instruction budget.

The override suggests many in Massachusetts — including parents, teachers, and lawmakers — support strengthening the state’s civics and history curriculum, particularly with mounting evidence of declined student performance across the country.

And yet, for the last 30 years — since the state passed the landmark 1993 Massachusetts Education Reform Act (MERA) — governors and legislators on Beacon Hill have steadily retreated from the legislation’s goals. MERA’s grand bargain included sharp funding increases for public education coupled with comprehensive academic standards, well-funded civics programs, and rigorous assessments to measure student aptitude and catalyze improvements.

Those reforms worked, helping Massachusetts go to the head of the class — nationally and internationally — on several major indices, including standardized test scores, college matriculation rates, and economic performance.

Nevertheless, the state’s fealty to the principles and objectives of MERA waned through the 2000s and 2010s.

Former Senate President Tom Birmingham, a MERA co-sponsor and Pioneer’s former Senior Education Fellow, lamented the stagnating civics and education funding in 2013, when he wrote that “in the last decade, support for public schools lost its primacy on Beacon Hill and state budgets reflect that. [Massachusetts’] inflation-adjusted education appropriation is the same as it was in 2002.” As Pioneer’s Jamie Gass and Charles Chieppo wrote in this 2019 article, state officials have failed to consistently follow through on MERA’s requirements and promises.

Lawmakers repeatedly postponed and, in 2009, indefinitely suspended the law’s requirement that U.S. history and civics be made part of the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) testing required for graduation from a public high school. With no state-level assessment of student aptitude in these subjects, lawmakers are unable to measure the state’s curricular efficacy.

Rather than rely on time-tested methods of measuring students’ knowledge and aptitude, Massachusetts’ lawmakers implemented naïve revisions to the civics curriculum. Those revisions often pushed aside serious study of the nation’s Founding era and the tenets of American political philosophy in favor of calls to activism and protest.

The latest proposed degradation to Massachusetts’ civics education came dangerously close to fruition this fall. Gov. Healey quietly vetoed a $500,000 increase for the Civics Education Trust Fund and instead proposed lowering the program’s budget by the same amount, to a meager $1.5 million.

To put these numbers into context, the Bay State’s overall budget for the coming fiscal year is nearly $60 billion, of which about $6.6 billion will be devoted to education.

The governor’s veto was a worrying sign for civics educators and enthusiasts. In mathematical terms, the veto asserted that just $1 of every $40,000 in state spending should be devoted to the Civics Education Trust Fund.

While Massachusetts remains one of America’s leaders in per-pupil K-12 spending, cutting this program by a half-million dollars would have sent a negative message to the rest of the nation about educational priorities in a state whose historical traditions resonate throughout the land.

Thankfully, advocacy groups from across the state lobbied Beacon Hill lawmakers to override Gov. Healey’s veto and guarantee more funding for programs that connect Massachusetts’ youth with the state’s famed civic tradition. The Legislature agreed, overrode the Governor’s cut in October, and restored the increase.

The Legislature’s action is cause for celebration, with an important caveat. Small budgetary victories are no substitute for a full commitment to the requirements of the 1993 education reform law. That Beacon Hill has refused to fully comply with the law for nearly 30 years is a troubling symptom in a state that aspires to be a wellspring of democratic citizenship and a model for the nation.

The $6.6 billion in annual K-12 money and $171.5 million on lunch programs are celebrated as examples of Massachusetts’ leadership in education. In a world of high per-pupil spending, policymakers should be able to find fiscal room for civics. As the following chart shows, the $2.5 million devoted to the state’s Civics Education Trust Fund is a tiny piece of the overall education budget for fiscal 2024.

Massachusetts should be expanding civics and history education, not retreating from it. And the state should reject recent trends and fads. As recommended in Pioneer’s latest book, Restoring the City on a Hill: U.S. History and Civics in America’s Schools, the state would benefit from abandoning “action civics” teaching standards that de-emphasize America’s common cultural fabric.

Given the declining performance on national civics assessments, restoring the long-discussed MCAS civics tests would give lawmakers a valuable barometer for student performance, helping to shape more effective curricular reform.

Supporting programs like the Civics Education Trust Fund would allow interested students from across the state to participate in non-partisan civics projects that they design and lead themselves. There’s no question that our democracy would benefit from kinder, less aligned, and more open-minded participants.

A comprehensive civic education program is essential to Massachusetts’ status as a leader in education. Given its history, tradition, and contribution to the American ethos, the Bay State has an obligation to embrace the teaching and testing of American history and civics — and a great deal to lose if it continues to retreat from its own traditions.

Jude Iredell is a Roger Perry Civics Intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is a senior at Pomona College pursuing a degree in history.