Cornell’s Margaret Washington on Sojourner Truth, Abolitionism, & Women’s Rights

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Margaret Washington

[00:00:00] Albert Cheng: Well, welcome back everybody to another brand new episode of the learning curve podcast. I’m one of your co hosts this week, Albert Cheng from the university of Arkansas and as usual have my stellar co host Alisha Thomas Searcy. What’s going on, Alisha?

[00:00:39] Alisha Searcy: Hello, I am doing well. How are you today doing?

[00:00:43] Albert Cheng: Well, keeping warm.

[00:00:44] We are getting hammered with some snow. I don’t know if it’s going to reach Atlanta, but here in the southern plains, if you will, where we’re getting a lot.

[00:00:53] Alisha Searcy: Yeah. And you may be sending some because I saw the news the other day that we’re getting more snow. And I want you to know that if we get snow in Atlanta, it’s like once a year in January and every other year.

[00:01:05] Not three times in a year. This is weird. It was cute the first day albert. It was wonderful, but we’re over it now until y’all can keep it Okay.

[00:01:15] Albert Cheng: Oh, all right. Well, i’ll do my best to get that memo to Whoever needs to hear that Well, hey, Alicia, we got a great episode today coming up. We have Professor Margaret Washington, who’s going to join us in a little bit to talk about Sojourner Truth.

[00:01:32] So we’re looking forward to that as we commemorate Black History Month this week and continue our series on that. But first we got some news to talk about and, you know, we’ve been, I guess, dropping the bad news, the sad news about NAEP scores. And I think you found another article related to this topic, right?

[00:01:50] Alisha Searcy: I did. And so this is actually more about money than it is Nate itself. So essentially a member of Congress like brought up a graph that was done by edunomics and we’ve had margarita and she’s amazing. And anybody who knows anything about education and reform, like she is one of the go to People on education finance.

[00:02:12] And so somehow there’s criticism of her work because the way that this graph was used by this member of Congress from California. He’s essentially saying that we don’t. This essentially proves that we don’t need more money in education, because if we did, then the NAEP scores would not be declining. And so I think this article points out a number of things.

[00:02:35] Number one is that, you know, you have to use the data for the purposes that it’s given, not just, you know, to create your own narrative. I don’t think any of us would argue that. When it comes to funding education that we need to get more clear, right, on what it actually costs to educate a child, and it’s not about how much you spend.

[00:02:57] I don’t think anybody’s arguing to just have, you know, this no limits to how much we spend on education. I think what many of us believe is that, yes, you need the right amount of funding, but we have to spend it in the right places. And these are the kinds of points that are important. Not quite brought out in this article, but it’s important to note again how you use your data.

[00:03:21] And in this case, the folks who are using this are pushing this narrative that we don’t need the Department of Education. We, you know, need to defund public education, like all of these things that when at the end of the day, when you’re talking about 90 percent of our kids in this country, attending public schools, Absolutely.

[00:03:40] They need to be funded correctly. Now, I am not one of those Democrats who believes, you know, just throw money at the problem and it’ll fix it because we can name a number of districts across the country. And we certainly have some in Georgia where they spend a lot of money supposedly on kids and they’re not getting the results.

[00:03:59] And so you have to dig deeper. And so the bottom line here for me in this. Particular article is, yes, we’re spending more money on education than we ever have, and we’re not getting the results. And so the answer to that is not let’s spend less money. The answer is let’s dig deep and figure out what we’re spending money on.

[00:04:18] For example, if you look at state departments of education, if you look at local school districts, in many cases after COVID, their staff went up 30 and 40 percent. Those dollars weren’t necessarily going directly to children in classrooms to impact their education. And so while we do need to look at how spending is done, and we do need to look at the effects of, and the return on investment on how we’re spending our funds using.

[00:04:49] Marguerite Rosa’s work to suggest that we’re spending too much money on education, we’re not getting the results, so let’s just stop, I think is insane. So you can tell that that article kind of, not the article itself, but the fact that this is used in this way is a little bit irritating for me. And the last thing that I will say, Albert, is it just speaks to the fact that those of us who do this education work, whether you are a practitioner, you are a researcher, whether you are, you know, an instructor.

[00:05:17] There’s so many nuances within public education that you really have to understand in order to make good policy. And I’ll be the first to admit that when I was in the legislature my first few years, I was just making policies but didn’t necessarily understand the impact of what I was doing. It wasn’t until I became a superintendent and led schools that I really came to understand Sometimes we can have good intentions, but until you’re living this every day and having to execute these policies, you may not understand its impact.

[00:05:50] And so I would just say, let’s continue to have more conversations. Let’s continue to use the data to make good decisions. And let’s make sure that the decisions that we are making are actually impacting. The educational experiences and outcomes of kids.

[00:06:05] Albert Cheng: Well, well said, and there’s certainly lots of nuggets of wisdom in that.

[00:06:08] You know, I appreciate that, Alicia. I mean, some of the things you mentioned about, you know, using data well and having discernment and good judgment and even asking the question, as you said, What aren’t the data telling us or what can’t, what can’t the data tell us? I mean, these are questions that I regularly post to our up and coming grad students who are, you know, learning data analytics to do education research for the first time, and these are important things that they, we all, you know, really have to wrestle with.

[00:06:34] So, yeah, thanks for sharing that wisdom from that story. Well, you know, I, I got a different article and, you know, this one just caught my eye because it kind of came out of, I mean, it didn’t come out of nowhere, it came from somewhere, but it wasn’t, I wasn’t looking for it. And I just thought that the title intrigued me.

[00:06:49] And, and as I dug in, I’m like, Oh, that’s interesting. I never thought about that. We talk a lot about college and career readiness when we refer to education as, you know, one of the goals of education. And the title of this article is our American high school students enlistment. ready. Um, which I’m like, Oh, that’s interesting.

[00:07:09] I mean, yeah, sure. I, I mean, you know, kind of everybody knows, I guess that a lot of our students go on to the military instead of college or a job, a conventional job right after. So this article intrigued me and essentially the article is proposing. That’s we do a better job of counting in terms of outcomes, not just college readiness or career readiness in the civilian workforce, but also to track students to get some sense of what proportion of students are joined in the military just to have that outcome data.

[00:07:39] And, you know, the article goes on to, I mean, you know, so at first I was thinking like, duh, we haven’t been doing this and, and the article kind of. explains that actually the data systems we need to follow students and aggregate this data, they don’t talk to each other. And so there’s actually work that needs to be done in states to have accurate counts of which students are going to the military.

[00:08:02] I mean, they were talking about examples of students that they don’t initially go to the military, but then they eventually go to the military, and then how these students get undercounted or lost. And so, you know, I think there’s this, it was interesting to learn about the practical questions of the record keeping associated with this, but, you know, philosophically too, it kind of raised this issue of, Hey, you know, we we’re, we’re good about counting college and career readiness.

[00:08:25] We emphasize that, but there’s a large swath of students that don’t choose those two pathways. And, you know, it’d be a good idea to kind of get a sense of how they’re doing, how they’re faring, you know, military life and certainly as civilians when they returned. So I thought this article kind of just, it was, it intrigued me.

[00:08:42] To say the least,

[00:08:44] Alisha Searcy: that makes a lot of sense. We talk about college and career ready. We don’t focus enough on the career part. And what are those skills and things that we want kids to have when they graduate? And I think it’s a part of also making their educational experiences more meaningful. Um, which we need to work on.

[00:09:02] So I love that. I appreciate you bringing forth that article because you’re right. We don’t, what is it? The saying goes, you, you measure what matters.

[00:09:11] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:09:11] Alisha Searcy: Yeah. We need to make sure that we’re measuring that enrollment as well. And they’re ready.

[00:09:15] Albert Cheng: Yeah. And, you know, to your point about career readiness, I mean, the article does mention some research out there that’s been done, essentially arguing that, you know, the military service is an important kind of career pathway for several, many of our students, many of our kids.

[00:09:33] And, you know, not to. Even mentioned the training that you get in preparation for jobs after the military. So yeah, yeah, yeah, you know So I think there’s something there to think through and consider Measuring, you know, and we want to measure what we value and yes, there’s some things there Exactly, so.

[00:09:53] Well, anyway, always fun to chat, uh, a little bit of news, education news with you, but hey, we, we should move on to our guests, professor Margaret Washington, who’s gonna talk to us about Sojourner Truth. So stick around. She’s coming up right after the break.

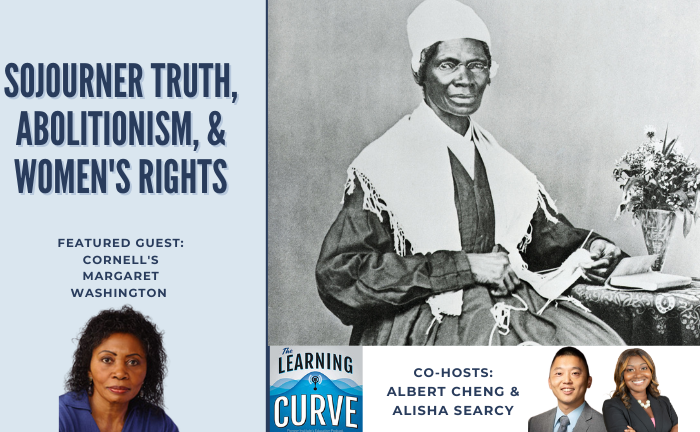

[00:10:10] Margaret Washington is the Marie Underhill Knoll Professor of American History Emerita at Cornell University. She is one of the foremost authorities on African American history and culture, African American women, and Southern history. Professor Washington is the author of the award winning book, A Peculiar People, Slave Religion and Community Culture Among the Gullahs, Sojourner Truths America, and the editor of the Knopf Double Day Edition of The Narrative of Sojourner Truth.

[00:10:51] Albert Cheng: She appeared on PBS, Ken Burns, Discovery Channel, and History Channel documentaries. Washington holds a B. A. from California State University, Sacramento, a master’s degree from New York University, and a Ph. D. from the University of California, Davis. Professor Washington, it’s a pleasure to have you on the show.

[00:11:10] Welcome. Thank you. Let’s begin with a little bit of your background. I mean, you’re an accomplished historian with a focus on African American history. Could you share with our listeners how you originally became interested in the topic? And then while you’re at it, let’s give a brief background of Sojourner Truth, who we’re here to talk about.

[00:11:29] Provide a brief overview of her life. Her character traits and what’s her enduring historical importance as an abolitionist and women’s rights activist?

[00:11:38] Margaret Washington: Well, sure. I moved to Cornell from UCLA and I was trained as a Southern historian, but at Cornell, I was going to start teaching women’s history. I was very excited about it.

[00:11:50] And of course, I knew something about Sojourner Truth and she was going to be a big part of my lecture and I found nothing on her. Other than the slave narrative that she dictated in 1850, which was in the rare book room at Cornell. And I read that and it had no introduction or anything. It’s just the straight narrative.

[00:12:12] And I said, well, this isn’t helpful. And I began to do a little bit of research and I really had a hard time finding out anything about her. And so I said, this woman needs an introduction to this narrative. And so I started doing research on that, and since I was a historian of the 19th century, I already knew about how important New York was, and I was living in the Burned Over District, which was the religious area that she started in as an activist, so I really got into the research on the narrative, and it was so much work.

[00:12:48] But I did it, and I did the introduction, and Vintage out of Random House published it, and I said, you know, I’m not ready to let this go yet. This is a fascinating woman, and I, I want to know more. So, that’s how I got into doing the biography. And I found out It was just an amazing, uh, journey for me because I’m a, trained as a southern historian.

[00:13:11] I know a lot about slavery in the South, and I knew a little bit about the North, but not a lot. And much of what I knew was about, related to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the early national era. So I really got into New York slavery and slavery in New England, and it was a fascinating journey for me.

[00:13:30] And story about this amazing woman who was born and raised in the mid Hudson Valley, didn’t speak a word of English and became an accomplished speaker with a tremendous sense of humor, an amazing sense of faith and a complete commitment to ending slavery of her people and also Very assertive about her rights as a woman.

[00:13:58] And that’s how I became a Sojourner Truth aficionado. The biography was a lot of work because she could not read and write. And I was in a position where I was trying to give a voice to someone who was not literate. And that was very difficult, but then it occurred to me In the process that that’s what I did with the Gullah Geechee people who were enslaved and couldn’t read and write and so I realized that giving voice to the so called voiceless was what I do.

[00:14:31] Albert Cheng: We’re grateful that you got into this work and are excited here to learn about everything you found here. So let’s get into the life of Sojourner Truth. So first of all, I don’t know if our listeners will know that she was born Isabella Bonfrey. Approximately 1797, just looking through my notes here of just some other facts.

[00:14:50] I mean, one of 10 or 12 children of an enslaved man captured from Ghana.

[00:14:55] Margaret Washington: Well, actually, you know, her name, they did not give enslaved people last names and her owners were named Hardenberg Dutch. And so bomb free. Was actually not her name, bam. Free was her father’s nickname. Her father’s name was James.

[00:15:13] They called him bomb free because Baum is the Dutch word for tree. And he was very tall and very straight. Oh, fascinating. And so, and then I presume that the free part came because he was a free spirit, but they called him Bum because he was so tall and straight. Ah.

[00:15:33] Albert Cheng: Oh, that’s, that’s fascinating.

[00:15:35] Margaret Washington: Yeah, and his nickname was Balmfree, but his name was James, and actually she named her first child James after her father, and the child died in infancy, but yeah, her name was simply Isabella, because enslaved people, North or South, had no last names.

[00:15:51] So, actually, they kind of called her, as an enslaved Dutch girl, Isabella Hardenberg, because she was enslaved by the Hardenbergs. And she was Dutch speaking. She was an adult before she learned English.

[00:16:05] Albert Cheng: You mentioned studying just slavery in New York state. Tell us a bit more about that context and other relevant details about her family and upbringing in that context.

[00:16:15] Margaret Washington: Sure. She, uh, was born in the Mid Hudson Valley. Her Owners were large slaveholders. The Hardenberg family owned close to two million acres of New York slavery, along with the Livingstons and other wealthy Dutch people. And they were Dutch Reformed, and her father and mother were the adult slaves on this farm because the Dutch did not have a large number of enslaved people.

[00:16:46] In their families, so they were the adults and then they had these children whom the Dutch, because they did not have plantations, they simply got rid of the enslaved children. And even though there were 10 or 12 children in her family, she didn’t get to know any of them except her younger brother. The other ones were either given away.

[00:17:12] or sold away. The Dutch often gave their relatives enslaved children as presents. And so she found her, many of her siblings when she grew up, but she didn’t know them as a child. That was the way Dutch slavery was. It was family slavery. And she was sold away. When she was about 10, because her second owner passed away, the Hardenberg son passed away.

[00:17:39] And she and her little brother, Peter was sold to different owners. Her parents were given their freedom because bomb free was old. And he was too old to do any good and also he had been their quote unquote top man on all of their land holdings and so they as a favor freed him and then the old man, the old Hardenberg made sure that he would be taken care of and he left money in his will, which unfortunately The family did not honor and her father died a very ignoble death, but he attempted to do that.

[00:18:16] The owner did. And the mother died when Isabella, whom they called Bell, was young, but she bonded very closely with her family, with her mother. And also the parents told her. Many stories about the children who had been given or sold away and she was able to find some of them and bond with them later, but she was very close to her parents, even though she was sold away from them when she was young, and that’s important because her mother.

[00:18:47] Taught her her faith and she later became a Methodist and kind of a Quaker too, but really an African Methodist. But her faith was more spiritual than denominational and she got that from her mother. And so before she ever entered a church, she had a spirituality because her mother told her about God and that God could answer all of her prayers and gave her her training about being honest, being faithful.

[00:19:20] And she used that in slavery because she was a quote, unquote, faithful slave and her father. What’s important to her because after her mother died, she formed a relationship with him and he would come and see her because he was free and he had no one else except her. He died very sadly because the Hardenbergs did not honor their patriarch’s wishes that old Bonfrey be taken care of and he froze to death.

[00:19:51] And that was very traumatic for her. And she says in her narrative that But I told God to kill all the white people. So she was very, very sad about that because that was, you know, that was her connection, her family connection.

[00:20:08] Albert Cheng: Well, let’s talk a little bit more about the world in which Isabella was in.

[00:20:12] And so, you know, New England at the time was the epicenter of the transatlantic slave trade, but then it later became home for the radical abolitionist movement. Could you just say a little bit more about the nature of Northern slavery? And then, you know, how do other figures, you know, names that we know kind of fit into this?

[00:20:29] I think of the enslaved Boston poets, Phyllis Wheatley, or some of the early abolitionists, you know, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass as well.

[00:20:38] Margaret Washington: Well, you’re absolutely right. New England was the center of the slave trade, especially states like Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

[00:20:45] And that was where the South got their slaves from. The fact is that New England also had slavery. They didn’t have as many as a state like New York. New York had the biggest slave population in the North. And Massachusetts had family slavery, as did Rhode Island and Connecticut. What was different, also, about a place like Massachusetts was that they had a system of slavery in which, for example, they often taught slaves to read and write.

[00:21:17] Isabella Was never taught to read and write throughout her life. She could not read and write. And so the slaves in Massachusetts had a much more advantageous opportunity for literacy. And Phyllis Wheatley is a very good example of that. Here was this child, no more than. Six or seven because she had lost her baby teeth when they bought her and Phyllis was the name of the ship that she came over on.

[00:21:48] But the Wheatley family recognized that this was a precocious little child who basically had almost a photographic memory. And was speaking whatever language she was exposed to, including Latin. And they took advantage of that and educated her. They bought her so she could be a companion for their daughter and also for the little girl.

[00:22:19] But then they began to teach her, and she was voracious in terms of learning. And then she became, they found out that she was not only a quick learner, she was artistic. And they began To allow her to write poetry, and she wrote amazing poetry. And eventually got her freedom, but one of the reasons she got her freedom was not so much because of her owner, was because she went to England, because of her owner, one of her owner’s sons was going to England.

[00:22:52] He took her with, with him, and one of the English gentry women became interested in her poetry and published it. Whereas in America, in the colonial America, when her owner showed her poetry to some of the people who would publish it, they didn’t believe she wrote it.

[00:23:10] So they refused

[00:23:11] Margaret Washington: to publish it. But the British published it, and so we have Phyllis Wheatley’s poetry, and she became so well known over there that She was freed by her owners,

[00:23:22] but

[00:23:22] Margaret Washington: her poetry is amazing and quite anti slavery much of it, as well as very religious

[00:23:28] because

[00:23:29] Margaret Washington: many African Americans, because they had so little else clung to faith.

[00:23:35] Albert Cheng: Well, we might have to have you back on to do a whole show on Phyllis Wheatley, but let’s let’s get back to Get back to talking about Sojourner Truth So fill in just a bit more of the detail of her early life. So in 1799, New York State She was

[00:23:51] Margaret Washington: sold away at 10 and sold to an Englishman Who beat her ruthlessly because she couldn’t speak English.

[00:23:58] And her father, who had his freedom, came to visit her. And he saw the way she was being treated. And she begged him to find her a new owner. And he did. He found her a Dutchman. Who bought her, but that was a, not a very good situation because there was a lot of alcoholism, the Dutch loved alcohol. And so she was purchased by another owner who was also Dutch, but much kinder.

[00:24:25] And that’s where she spent the next, Oh, 13 or 14 years. That’s where she grew up,

[00:24:31] the

[00:24:31] Margaret Washington: Dumont family. And that’s where she married in the way that the slaves married, which is not a legal marriage, but that’s where she had her children worked very hard. Called herself a model slave and came of age there in the Dutch community and was a very hard worker but never forgot the way her father died and never forgot her mother’s training and never lost a will to be free.

[00:25:00] And basically, once her owner told her she was such a good worker that he was going to free her early, and once the New York legislature passed an emancipation law, then she decided that if he wasn’t going to honor her by basically keeping his promise, then she would take her freedom. And so She ran away with her baby daughter who was still nursing.

[00:25:25] It’s a wonderful story. He did not free her when he said he would and so she went out to her little place of refuge and talked to God as her mother had told her to do and According to her God told her to leave so she got her baby and she left and she went to the Quakers And the Quakers helped her, and once the man, her owner came to her to take her back, she went to her other friend, who was also Dutch, but was kind to her and really believed in freedom, and he paid for the little baby.

[00:26:01] 5 for the little baby

[00:26:04] and

[00:26:04] Margaret Washington: 20 for her because that’s all that was left of her time

[00:26:08] and

[00:26:08] Margaret Washington: that’s how she got her freedom.

[00:26:10] Wow.

[00:26:10] Margaret Washington: And then she became, her first name was Isabella, she had no last name. She took the name of the owners, of the people who had helped her get her final freedom, which was Van Wagenen.

[00:26:23] And so she became Isabella Van Wagenen. And then she started going to Methodist meetings in her freedom, and she embraced Methodism and began to preach about freedom and to tell people how she got her freedom, because she claimed that God had given her freedom. God had given her the will. to challenge the slaveholders and that was the beginning of her faith.

[00:26:51] Albert Cheng: Yeah, let’s talk about that a bit more, you know, and you just talked about her taking on a new name. I mean, let’s, let’s fast forward a bit to 1843 on Pentecost Sunday, which is when she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. And so this was during the Second Great Awakening. And so a lot was going on at that time.

[00:27:09] So can you discuss this era of religious revival and and social change, really, that’s happening. How did all that impact her life and her own views and religious convictions about improving American society?

[00:27:23] Margaret Washington: Well, yeah, the Second Great Awakening was instrumental in many ways. It was an age of dynamic change, socially, And politically, and of course economically, because it’s also the age of America’s first Industrial Revolution, which is creating a lot of poverty, a lot of want, and it was also the rise of slavery.

[00:27:46] The Great Awakening corresponds with what we call the antebellum era, the era before the war, the Civil War. So, there were many wrongs in American society. It was an age in which people believed that the kingdom of God was at hand. And that if Jesus came to America, nobody would be saved because there was so much evil in the world.

[00:28:11] The worst evil of all was bondage, and the slave power had risen during the age of the Great Awakening. And so this irreligion, this infringement upon individual rights would be very displeasing. When Jesus came, because this was the age of the millennium, and since the worst societal ill was bondage, then the people of the Great Awakening, many of whom were abolitionists, said this is, this is our major challenge.

[00:28:45] And even though they believed in many other reforms, this was the one that was the most egregious. And so that gives rise to the abolitionist movement. And Isabella Van Wagenen has moved to New York City, where she is a well known preacher. And she’s involved in a lot of things. Some are very significant, some are pretty ignoble.

[00:29:08] But she stays the course as a preacher. And then finally in 1843, it’s kind of a sad story. It’s an enlightening story, but it’s also sad because she leaves the city. Because she wants to make change, but also because her beloved son, her only son, who had shipped out to sea, did not come back, and she had waited for him, but the ship came, he was on a whaler, the ship came back, and her son did not, and this was the son, and this is a great story that We haven’t even talked about, and that is her getting her son back who had been sold into slavery in the South and the Quakers helped her get him back.

[00:29:51] And he came of age, shipped out to sea, wrote her beautiful letters of how he was going to come back and help her. And he never came back. So that along with the disappointment about what was going on in the world inspired her as well as her faith to leave the city. And she went to Northampton, which was one of the reform centers of anti slavery in the East.

[00:30:19] And there, she met William Lloyd Garrison, the woman who helped her write her slave narrative, Olive Gilbert, and many People who are involved in the anti slavery movement, and she began to talk about her experiences in slavery, and they were mesmerized, and they wanted her to write her narrative, and of course she couldn’t read and write, and so she dictated it, she took to the road, telling her story, About slavery and selling her narrative.

[00:30:54] And then as they say, the rest is history.

[00:30:57] Alisha Searcy: Wow. I want to talk about that for a moment, professor, but I want to ask just a clarifying question. You mentioned a few minutes ago that the Dutch, or perhaps what slavery looked like in Massachusetts versus other places, you mentioned a family slave. So can you talk about the difference between a family slave and what that looked like in Massachusetts versus.

[00:31:21] In the South what slavery looked like.

[00:31:24] Margaret Washington: Oh, yeah. Family slavery was where you owned two, three, probably four at the most enslaved people in a family. They worked in your home. They lived in the home. They often slept by the hearth. They might have their own space, but oftentimes they didn’t. So they were part of the family, and that’s why when you had too many, you would seldom, or give them away usually to relatives.

[00:31:51] In the South, enslaved people, first of all, there were many plantations where you could have 50 to 100, 200, and sometimes 500 enslaved people, so they had their own space, slave quarters, and consequently that, in terms of African Americans, created different cultural milieus, because enslaved people lived among themselves, created their own Cultural bonding, which is what I studied when I studied the Gullah people, whereas in a place like Massachusetts or even in New York where Bell was, the enslaved people grew up around whites and were more a part of the general culture, and that created I wouldn’t say closeness, but it created proximity and that was the difference.

[00:32:47] Alisha Searcy: Thank you for that. That’s, I think, a really important distinction to make. So I want to go back to, we were talking about how Sojourner Truth now. began making speeches and talking about her experiences. In 1851, she went on a speaking tour across New York State and attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, where she delivered her famous speech that I learned in elementary school, known as Ain’t I a Woman.

[00:33:16] Can you

[00:33:17] Alisha Searcy: talk about this oration, its historical importance, and what educators and students today should know about it?

[00:33:24] Margaret Washington: Okay, and thank you for bringing that up, because that was a turning point in terms of her national reputation. Before that 1851 speech, she was regionally known. They knew her in New England, and they were getting to know her in New York, but not Well, that made her known in the West, what we call the Midwest today.

[00:33:46] And she gave that speech because her narrative had come out and her friends in New York had asked her why she didn’t spread the word out. And she met some Ohio women and they heard her. In New York, and they said, come to Ohio, and she did, and she went there to do abolitionist lectures, but she heard about the Women’s Rights Convention, and she believed in women’s rights, and so she went, and they were not happy.

[00:34:18] To see her, many of them, especially the leadership, but there she was, and because she was a well known speaker in the East, she went right to the front, didn’t sit on the stage, because she was not invited, she sat on the steps, but she kept interjecting comments, and finally she couldn’t stand it, and she said, may I have a few words, and The president said, all right, and let her speak.

[00:34:47] And the speech that you learned in school is, unfortunately, not what she said. But she did say words that were extremely important. Now, first of all, I have to say, I don’t know what you learned, but the traditional speech that people learned was full of slang, African American dialect. And also the n word, and that is not what she said.

[00:35:16] We know now what she said because in the process of doing research on her, I and a couple of the other biographers found the actual speech. And the speech, which I’m publishing in an article at the end of this year, is, I am a woman’s rights. And she gives A scenario of all of the work she did as a woman, which is as much as any man.

[00:35:47] And she plowed, she dug, she hoed, she did, and she worked in the wheat and the barley and the oats. She didn’t work in cotton. So she talked about that, and she talked about having given birth to five children. And she also talked about Jesus. And because the men in the audience were saying that women had no right to speak.

[00:36:13] And she talked about women who were the first to declare the risen Jesus. And then she said, how did Jesus come into the world? God, who created him, and a woman who gave him birth. And men, you had no part in it whatsoever. She gave a very respectful speech. She did not. Use the n word. She did not say she had 13 children as the the fable It was presented for many years, but she gave an amazing speech and won a place for herself in women’s history as a result of that.

[00:36:56] But it made her prominent, not only in the anti slavery movement, but also in the women’s rights movement. And that was really the beginning. And then, The next two years, when they had the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, she was one of the major speakers. But that was the beginning of her recognition as a women’s rights advocate, and it went right along with her popularity as a lecturer in Ohio.

[00:37:26] And she stayed in Ohio for a year and a half. And even when she left, they didn’t want to let her go. And they gave her a huge banner. When she left, a silk banner that she, the first time she furled it out was at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York City, where she gave a speech after she got back from Ohio in 1852.

[00:37:49] And it said, Am I not a woman and a sister?

[00:37:53] Alisha Searcy: Hmm. Wow. What powerful history to know. I can’t wait until you publish the real speech so that we can.

[00:38:01] Margaret Washington: It’s going to be published by Bloomsbury and a handbook on African American women. And it’s called Sojourner Truth. Renaming her speech, reclaiming her voice.

[00:38:14] Alisha Searcy: Woo. I love it. I love it. Can’t wait for that. Thank you for doing that. I want to move forward talking about during the Civil War, where Sojourner Truth helped to recruit black troops for the Union Army, and after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people.

[00:38:35] Can you talk about those speeches and her advocacy and the efforts to? enable formerly enslaved people and women’s rights before, during, and after the Civil War?

[00:38:45] Margaret Washington: Yeah, when the war came, because as we know, the Civil War was initially not fought over slavery. It was fought over rights, constitutional rights versus states rights.

[00:38:57] And so there was a lot of controversy during the first couple of years, especially So the abolitionists continued to preach anti slavery during the war, as did Sojourner Truth. So much so that she became ill during the war. She almost died, and then when she began to get well, she decided that she was going to go to Washington.

[00:39:23] and recruit troops. By then, it was too late because black men were already in the army, including her grandson. Her grandson served in the Civil War. Frederick Douglass’s two sons served in the Civil War. So they were adamant that this war was going to be to end slavery. And by the time she was well enough to get back on the circuit.

[00:39:48] The Emancipation Proclamation had been signed and that was January 1, 1863. By April of 1863, she was ready to get on the road again. And Sojourner went to Washington. She met Abraham Lincoln. And she was very active among the freed people in Freedman’s Village in Washington, D. C. Lincoln encouraged her to go and work among her people, and that’s what she did.

[00:40:16] And she stayed in Washington until 1867. Working among the freed people, doing all kinds of activities. Working at Freedman’s Hospital. Working at the area that was going to be Freedman’s Village. She worked among the women’s rights advocates. And she did something that was really amazing. By then, Sojourner Truth, in the 1850s, late 1850s, she relocated to Michigan.

[00:40:45] She created, along with two other white women abolitionists, a network. of employment for the freed people. She created this network in New England and in New York and in Michigan and used her network of friends to get freed people jobs in other states. She had basically an employment bureau in Washington.

[00:41:14] And she did that at the same time she was working with women to Create a system that actually became Reconstruction because women, especially women, were concerned about what was happening to the newly freed people in the South, that they were being ruthlessly treated as they got their freedom. So they were working on that and trying to help.

[00:41:37] Trying to get the Congress to pass legislation to help the freed people as they emerged out of slavery. So she was doing that and she was working on women’s rights, working on how women can get the vote. So she was doing all this networking, but her main concern was finding employment and getting freed people out of Washington DC because it was just overcrowded and there wasn’t enough work for them.

[00:42:05] Alisha Searcy: Incredible. And so Sojourner Truth died in late November of 1883 at her home in Battle Creek, Michigan, and the celebrated abolitionist statesman Frederick Douglass delivered a eulogy for her in Washington, D. C. saying, quote, venerable for age, distinguished for insight into human nature, remarkable for independence and courageous self assertion.

[00:42:29] Devoted to the welfare of her race, she has been for the last 40 years an object of respect and admiration to social reformers everywhere, end quote. Can you talk with us about her public reputation and fame like that at the time of her death?

[00:42:47] Margaret Washington: At the time of her death, she was so well known, she had, I mean, my last comments were about her during the post Civil War period, moving into Reconstruction.

[00:42:59] At the time of her death, she was deeply involved in the Kansas movement. Sojourner was such a humanitarian, it wasn’t just about slavery, it was about progress. And when she saw what was happening during Reconstruction, when she saw African American people being hanged and burned, women being raped, people not being able to walk on the streets, she thought about all of the land.

[00:43:30] In the West, and her attitude was, our people do not have to take that. There’s all this land out in the West, and so she and many of her friends who, they’d worked together during the anti slavery movement, became involved in the Westward movement. Went to Congress to Get them to set aside a land for the people who had been in bondage so that they could have homesteads of their own.

[00:44:01] And she was very serious about this movement. She spent time in Washington. Her grandson, who was a teenager by then, became her eyes and ears and her traveling companion. He would travel with her to Washington and All over the Northeast, she was back and forth to New England, in New York, speaking to people about a homeland for the African American people.

[00:44:28] This was her, if you will, colonization movement, but it was within the United States. And this became, after she passed away, the legacy of what she and her friends did became what was known as the Exodusters movement. And she doesn’t get enough credit for this. She began that. And she died before it reached its fruition, but that’s what the Kansas Movement was about, and none other than Sojourner Truth began that.

[00:44:57] And one of the editors of a Kansas newspaper wrote when she was in Kansas, he wrote in her book of life, You say that you wish to leave the world a little better than you found it. History will record your having done so. And he was referring to her activities in Kansas.

[00:45:19] Alisha Searcy: Wow. So we’re at the end and I’m going to ask one more question and then ask you to close us out by reading an excerpt from your book.

[00:45:29] But my final question is, can you talk about Sojourner’s legacy today as you have talked a little bit about and what we hope citizens, educators, and young people alike might know about our abolitionism? Her advocacy of women’s rights, as well as her role as a powerful symbol and legend in history today, as you’ve really helped us to learn.

[00:45:52] Margaret Washington: I look upon Sojourner Truth as, certainly she was an abolitionist, certainly she was an advocate for women’s rights. But she was an advocate for human rights.

[00:46:04] Margaret Washington: She was an advocate for the rights of everyone. Sojourner Truth was a humanitarian. It wasn’t just about Black people. It was about all people. And I think that that’s the most important legacy that Sojourner Truth left with is that it wasn’t just about her people.

[00:46:23] It was about all people. And she was, she revered people. She was about love. I mean, one of the things she talked about was how she loved the Quakers. And it was because she felt that the Quakers were about everyone. They were about love. And the word that they used was friend. Which is a biblical term. It comes out of the Bible with Jesus saying that his disciples were not his servants, they were his friends.

[00:46:48] And that’s what the Quakers embraced. And her attitude was that this is about humanity. And in a broader sense you could say this is about America. And that’s why I wanted to use the title, and my editors and I went round and round about this, but I wanted to use the title Sojourner Truths America.

[00:47:07] Because she was About the America as she knew it, and if it needed changing, she wanted to be a part of that change, but it was about everybody. It wasn’t, and I think that’s an important message. I think it’s an important message for us today, and certainly her cohorts, the people whom she bonded with, that’s what it was about them.

[00:47:29] So that if you take the women whom she was so close to, and not just women, men as well, that after the Civil War. When they saw what was happening to black people, they realized that ending bondage was not enough. And women were behind the period that we call Reconstruction. Women were writing to Senators saying, because the abolitionist women went South, just like Sojourner Truth did.

[00:47:53] And they wrote back and said, the people are. They’re free, but they’re not free. You need to do something else. And they were the ones who encouraged Reconstruction. They were the ones who encouraged the Kansas movement. That once you make progress, you have to continue. That’s what America is all about. It wasn’t just about ending slavery.

[00:48:16] It was about equality. It was about making everyone the same. And opportunities for everybody progress, something that was open to everyone, blacks, women. That’s why she worked for Kansas. That’s why she worked for the 15th amendment. And once the 15th amendment was passed, and if you read my book, you know, that there was a big conflict between people who had bonded together over slavery and ending slavery.

[00:48:48] And they broke with each other over black men getting the vote over women. What Sojourner Truth said was she worked for black men getting the vote. Once that happened, then she said, okay, I have another cause and that is I’m a woman. I want to vote. As a woman, so she worked and women’s rights. So I think it’s about everybody.

[00:49:13] And that’s the what Sojourner Truth. I think that’s her most important legacy was that it was about all Americans, not just some of us. And the people who were the most needy in her lifetime were black. And that was her cause. And then the next cause was women. And then the causes continue on until the causes we have today which are much more complex but nonetheless deserving.

[00:49:40] Alisha Searcy: Wow. Thank you very much. Um, we’d love to hear a short excerpt from Sojourner Truths America.

[00:49:48] Margaret Washington: Okay. That was a hard one. I thought, you know, that I would read A little bit from the Battle Creek, this is a, an excerpt, it’s actually from the Battle Creek Journal, and it’s about going to Washington. She was there when the 15th Amendment was ratified, when they brought it into Congress, into the chamber, the Secretary of State was Hamilton Fish from New York, and the halls of Congress were full, and of course Sojourner Truth was there, and it was a very momentous.

[00:50:19] Time, and the Battle Creek Weekly Journal was there, and this is what they wrote. It was our good fortune to be in the marble room of the Senate chamber a few days ago, when that old landmark of the past, the representative of the former gone age, Sojourner Truth, made her appearance. It was an hour not soon to be forgotten, for it is not often that we see Revered Senators, even him that holds the second chair in the gift of the Republic, vacate their seats in the Hall of the State to extend the hand of welcome, of praise and substantial blessings.

[00:51:04] But it was refreshing as it was strange to see her Who had served in the shackles of slavery and the great state of New York for nearly a quarter of a century before a majority of these senators were born now holding a levy with them in the marble room where less than a decade ago, she would have been spurned from its outer corridor by the lowest menial, much less taking the hand of a senator.

[00:51:36] Now she pledged to devote more time to women’s suffrage. It is her intention to leave here in a few days, as she desires and expects to be in New York City during the anniversary week, that she can attend the women’s suffrage meeting, a cause which she is deeply interested in. End of quote.

[00:51:59] Alisha Searcy: Love it. Thank you so much.

[00:52:01] I think you said it best at the beginning that you are here to give voice to the voiceless. So thank you so much for sharing with us the history, the work, the legacy of the Sojourner Truth. It means a lot for you to be with us today, Professor.

[00:52:18] Margaret Washington: Thank you. It’s been a real pleasure. I love talking about the Sojourner and we are still Sojourning, are we not?

[00:52:25] Yes, we’re we’re

[00:52:29] I.

[00:52:40] Albert Cheng: That was a fascinating interview, Alicia. I mean, I don’t know about you, but you know, I, of course, you know, the name Sojourner Truth, but, uh, really get into the weeds of her legacy and her life. That was a treat.

[00:52:52] Alisha Searcy: Super inspiring, just as I expected it to be. And, you know, again, I appreciate. that we’re celebrating Black History Month and just being able to learn the stories of incredible human beings that have walked this earth that before I think have been romanticized, but now we get to hear real stories about their courage and heroism.

[00:53:13] So yeah, yeah.

[00:53:15] Albert Cheng: Yeah. And that’s really one thing we want to do on this podcast, you know, to feature the lives of those that have come before to inspire us, as you say, and to learn from. Well, it’s time to close out the show. So let me give the tweet of the week. This one comes from us news education, and I guess maybe I’m too much of a sucker for rankings.

[00:53:33] This one is the rankings of the best biomedical engineering or bio engineering graduate programs in the U S the only comment, Alicia, that I have about this is that My alma mater, UC Berkeley, was ranked 6th, but it was ranked below our arch rival Stanford, who was in a, I think it was like a four way tie for number two.

[00:53:58] So, anyway, I guess my Berkeley loyalties aren’t that strong. It’s been a while, but all my, you know, friends that went to Cal and are still way into this rivalry, well, I’ll leave that ranking to you to argue over and complain about.

[00:54:14] Alisha Searcy: I love it.

[00:54:16] Albert Cheng: Alicia, thanks again for co hosting with me this week. Before we leave and close out this episode, just to tease next week’s episode, we’re going to have Samuel Lee Fudge.

[00:54:25] It’s going to be a real treat. He’s an actor, writer, director, and producer, and also notably the first actor to portray Marcus Garvey in the narrative film Messiah, which is a project that he also wrote. So that should be a treat. Very cool. Until then, everyone be well and catch you next time. See ya. Hey, it’s Albert Cheng here, and I just want to thank you for listening to the Learning Curve podcast.

[00:54:50] If you’d like to support the podcast further, we invite you to donate to the Pioneer Institute at pioneerinstitute.org/donations.

In this week’s episode of The Learning Curve, co-hosts U-Arkansas Prof. Albert Cheng and Alisha Searcy interview Margaret Washington, the esteemed historian and author of Sojourner Truth’s America. Prof. Washington delves into Truth’s remarkable life, from her early years in slavery in New York to her transformation into a powerful abolitionist, women’s rights advocate, and religiously driven reformer. She explores Northern slavery, the Second Great Awakening, her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, and her Civil War-era activism. Prof. Washington also reflects on Truth’s enduring legacy as a symbol of justice, equality, and resilience in American history. In closing, Prof. Washington reads a passage from her book, Sojourner Truth’s America.

Stories of the Week: Albert analyzes an article from Education Next on if American high school students are enlistment- ready. Alisha discusses a question raised in an Education Week article, does money matter for schools?

Guest:

Margaret Washington is the Marie Underhill Noll Professor of American History Emerita at Cornell University. She is one of the foremost authorities on African-American history and culture, African-American women, and Southern history. Prof. Washington is the author of the award-winning book “A Peculiar People”: Slave Religion and Community-culture Among the Gullahs; Sojourner Truth’s America; and the editor of the Knopf/Doubleday edition of The Narrative of Sojourner Truth. She’s appeared on PBS, Ken Burns, Discovery Channel, and History Channel documentaries. Washington holds a B. A. from California State University, Sacramento, an M.A. from New York University, and a Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis.

Margaret Washington is the Marie Underhill Noll Professor of American History Emerita at Cornell University. She is one of the foremost authorities on African-American history and culture, African-American women, and Southern history. Prof. Washington is the author of the award-winning book “A Peculiar People”: Slave Religion and Community-culture Among the Gullahs; Sojourner Truth’s America; and the editor of the Knopf/Doubleday edition of The Narrative of Sojourner Truth. She’s appeared on PBS, Ken Burns, Discovery Channel, and History Channel documentaries. Washington holds a B. A. from California State University, Sacramento, an M.A. from New York University, and a Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis.