MIT’s Nobel Winner Joshua Angrist on the Economics of Education & Charter Public Schools

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Joshua Angrist

[00:00:00] Alisha Searcy: Welcome back to The Learning Curve. I’m your host, Alisha Thomas Searcy. In my day job, I am the Southern President of Democrats for Education Reform and Education Reform Now. And Albert is out again this week. Of course, he’s on paternity leave. We welcome that beautiful little baby to The Learning Curve family. And I have a guest co-host with me this week. Mike, would you tell everybody who you

[00:00:45] Mike Goldstein: Hey, Alisha. I’m Mike Goldstein. My day job is founder of the Math Learning Lab at QMath. And also, I’ve worked with our guest, Josh Angrist, a few times before, both about charter school research and about how to use his algorithms to improve school choice systems.

[00:01:04] Alisha Searcy: Very interesting. I think this is going to be a fascinating interview for sure. So, thanks for joining me this week.

[00:01:10] Mike Goldstein: You bet.

[00:01:12] Alisha Searcy: So, let’s jump into the stories of the week. And as always, there are often great stories that we could talk about. And the one that I want to focus on, Mike, is from The Independent, and it’s called Here are the best and worst states for your child’s education.

[00:01:28] and You know, we’ve seen these studies before, the education system in the United States has been studied quite a bit. We’ve done that internally and externally. And so, what we know is that many states that are at the top have been at the top for a long time. One of them I know you’re very familiar with, Massachusetts ranks at the top, along with Connecticut and Maryland.

[00:01:51] And those that are at the bottom, unfortunately, are New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Arizona. And so, I appreciate this story for a couple of reasons. Number one, we need to know where we stand in terms of education, who’s doing it right. And at Democrats for Education Reform, we recently, in our policy department, released a study on schools that are high performing.

[00:02:14] Many of them have all of the challenges that you see in public education, but they talk about what are the things that are common amongst those schools, those high performing schools. And again, not to be surprised, Massachusetts is one of those states, Colorado is another one, where they’re finding some of the best practices.

[00:02:33] What’s also important in this study is talking about safety. And so, with the share of 20 points, they included youth incarceration. The share of threatened or injured high school students, the number of school shootings, and bullying incidences, and existence of a digital learning plan. It’s important for us to talk about not only the quality of the public education system in this country, it’s also important to talk about how safe it is for kids to go to school.

[00:03:03] I appreciate this part of the story, and I think what these kinds of stories do, Mike, is help us to just as the study that I mentioned. that we’ve done at Education Reform now is let’s dig in what’s happening in these states that are diverse in particular, right? We’re talking about racial diversity. We talk about geographical diversity when we talk about students who are low income.

[00:03:29] And I think what we will find is regardless of those demographics, When you have high expectations for kids, when you have a strong curriculum, when you have systems in place, when you have norms, and I know you know this as a charter school leader, you know that those are the things that we need in place to have a high quality public education system.

[00:03:49] And I should also mention assessments. So that you can measure how students are doing, and then with that information, you can put in the supports that is needed for those students. So, great story. I hope people will check it out. And I’m definitely curious about your thoughts, Mike, on this one.

[00:04:07] Mike Goldstein: It’s interesting. I have a related story to yours. So, mine was, I read an editorial written by the Newark Star Ledger. So, this is their editorial board. And the headline is, In Newark, Wasting Money to Sabotage Charter Schools. So, sabotage, right? So, I was like, ooh, that’s good, let’s see what’s going on. So, the context here is one that you know well, which is, there’s a long running battle between the Newark School district versus the Newark public charter schools.

[00:04:43] It’s sort of like a Goliath against a bunch of Little Davids. But there’s a third player in this battle, and that’s the state. And the former New Jersey governor supported charter schools, but the current governor, New Jersey governor opposes charter schools. So that’s the background. In this case, an empty building was for sale, and a few charter schools that have long waiting lists of parents who want to go to those schools bid on this building.

[00:05:12] And then the school district got wind of this. So, what happens next is speculation, according to the editorial, which is, what we know is the district then the state to buy up the building, so none of the charters could buy it, and the state paid like 15 million, even though the building was appraised at like 8.

[00:05:35] 5 million. And then the state gave that building to the school district, which promptly opened a brand-new school district. District school there. And the editorial is sort of saying, hey, wait a minute, the district didn’t need a new school. Their current district schools in that area were under enrolled already. They had a lot of empty seats. Yes.

[00:05:59] Mike Goldstein: And so, the speculation, which to me seems quite plausible, is they just wanted to mess with the charter schools and make it harder for them to follow through. and build more campuses to meet the demand of families on their waiting list. So that was the sabotage that they, in their frame, they’re saying they’re speculating this. They don’t have hard evidence that the state bought it just to spite the charters, but it certainly passes the sniff test to me.

[00:06:28] Alisha Searcy: For sure. And we all know that facilities is probably the most significant issue impacting charter schools. And we should be asking the question, why a charter school that’s a public school even has to bid on a public building? But that’s a story for another day, isn’t it?

[00:06:47] Mike Goldstein: It is. Story for another day.

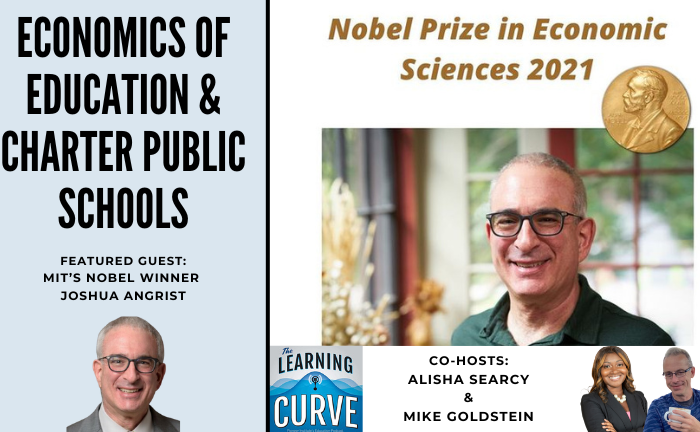

[00:06:50] Alisha Searcy: So, thank you for that story. Looking forward to our guest today, Professor Josh Angrist, and he is a Nobel Prize winner. So, stay tuned. Professor Joshua Angrist is the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT. A co-founder and director of MIT’s Blueprint Labs and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. A dual U.S. and Israeli citizen, he taught at Harvard and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before coming to MIT in 1996. Professor Angrist received the Nobel Prize. In economic sciences in 2021, and he received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Oberlin College and completed his PhD in economics at Princeton.

[00:07:48] Professor Angrist we are truly honored to have you today, and so we wanna jump right in and ask you a few questions. The first one is you are a Nobel Prize winning economist. who was born in Ohio and grew up in Pittsburgh. So, can you talk to us about your family, your upbringing, your formative educational experience, and how this put you on the path to become a world renowned academic?

[00:08:14] Joshua Angrist: Well, that was a long time ago. I was born 63 years ago in Columbus, Ohio. My parents were students at Ohio State, and so that’s where they had me, their first child. And then they got their first jobs at universities in Pittsburgh. My dad at Carnegie, and my mom at Pitt. And so, they moved to Pittsburgh, and that’s where I grew up.

[00:08:36] Even though they didn’t stay in academia. They didn’t like academia very much. So, it’s a little ironic that I ended up being a professor. I think my dad in particular hated academia. But I grew up in Pittsburgh. I went to high school in Pittsburgh. I didn’t do much schoolwork. I hated school and mostly blew school off.

[00:08:55] And I figured out that I could 11th grade by taking two of every Required course, I took the easiest versions. I took two healths, two gyms, and two Englishes, because that was all that was required at that time in Pennsylvania. We didn’t have, like, the MCAS in Massachusetts, nothing like that. Also, you didn’t really have to go to school, so I skipped a lot of school.

[00:09:20] And I went to work for a while. I worked in various institutions for mentally handicapped people, because I had done that in the summer. Then I decided I should go to college, so I went to Oberlin College. I was lucky to get in. I sort of talked my way in. And there I discovered economics. That’s the beginning of economics for me.

[00:09:42] I had a great Econ 101 teacher, a man named Robert Perron, who unfortunately passed away last year. And I just thought his class was so much fun. I love the content. I also liked his style, which I adopted in some ways. He was very in your face, you had to pay attention, he was cold calling. A little bit like and no excuses Charter might be except on steroids, you know, and of course some of the things that you do in Charter K 12 we’re not doing there, like with the fingers and all that, but I love the content as well as Bob Perron’s class.

[00:10:20] I thought it was super stimulating and fun. Not everybody loved it, but it really connected with me. And then I thought economics is so interesting. I had initially gone to take psychology and I thought I might do special education because I’d been working, you know, full time in that area. But then intellectually, I didn’t engage with it.

[00:10:39] And economics was fun, and so I just took more econ courses. And then I realized I didn’t know any math, so I better take some math. I had stopped taking math in 10th grade and didn’t really learn anything in 10th grade anyway. So, I had to catch up and get tutored in math and stuff. So, I got really into economics.

[00:10:58] And by the time I was a senior, you know, I was an econ and math major, and I did an undergraduate thesis, which was a great experience for me, writing a paper, doing some actual independent scholarship. And Oberlin doesn’t have graduate students, you know, it doesn’t have PhD students. And so the undergrads who write an honors thesis, they’re sort of the best students and they get a lot of attention and a lot of faculty input.

[00:11:28] So I really love that. Another good thing about Oberlin is they still have, uh, an outside examiner comes. The faculty at Oberlin are good teachers, but they’re not really well-known researchers. So, they bring in somebody who’s got a higher research profile. And they brought in, uh, Orley Aschenfelter from Princeton, and he’s the guy who ended up being my thesis advisor.

[00:11:51] So I met him as a senior in college, and then he was the outside examiner for the Oberlin Honors Program, and we got along great. Orley, I think it wasn’t a coincidence, my advisor, Hirsch Kasper, who’s a labor economist at Oberlin, Who I think also passed away recently, unfortunately. Hirsch was friendly with Orley, and he knew what I was working on, and I think that prompted him to ask Orley if Orley would come.

[00:12:17] I was very lucky, you know, you can’t take for granted that somebody who’s a busy, high-profile scholar will come and spend a couple days in Oberlin, Ohio, talking to undergraduates. And Orley was that kind of guy. My work was somewhat related to his, but mainly he saw in me the potential, you know, to do economics and do research.

[00:12:38] And he wrote me a letter inviting me to go to Princeton. Amazingly enough, I didn’t take him up on that at that time. I graduated from Oberlin. I was very happy. I felt like I learned a lot and I liked economics, but I wanted to do other things in the meantime. So, I had gotten interested in Israel, I had visited Israel as a junior, that was my first time overseas.

[00:12:58] I was actually at the London School of Economics visiting, but then I spent a vacation. From LSE in Israel, and I discovered a lot of family connections there. So, I had kind of made a pact with my best friend from high school that we would move to Israel together when we got out of college. My friend named Mike Drescher.

[00:13:17] So we did that together and we ended up becoming Israeli citizens and getting drafted and met our future wives and all that. Initially I was a student at Hebrew University. I didn’t do very well there. I was kind of set back again on my heels. It was a challenging master’s program. It was mathematically very sophisticated.

[00:13:38] It was also in Hebrew, and I didn’t speak Hebrew that well at the time. So, I dropped out of Hebrew. I got drafted. into the Israeli Army. I served there for two years with Mike initially. That’s something we decided to do together. Then when I got out of the Army, kind of long story short, I spent two years in the Army and, you know, I had time to think about graduate school.

[00:14:00] And the Army has its pluses and minuses, but it makes graduate school look really good. So, I married my girlfriend, who became my wife. I got out of the army two weeks early for that, so that was already worth it. And then I wrote, or called, Orly in the spring of, I guess it must have been 1985. And I said, do you remember me?

[00:14:25] You said I should go to Princeton, or I could go to Princeton, and you would take care of me, and now I’m ready, will you take me? And he said, sure, come in the fall. So that was that. You can’t actually do that at MIT, where I teach. You can’t just tell somebody to come, you know, and so I was also lucky there.

[00:14:45] Though one of my other thesis advisors, Dave Cart, I told him that story. Of course, he knows that story well by now. And I said, you know, Dave, the way Orly just told me to come to Princeton and he would take care of the funding. I can’t do that at MIT. I don’t have the authority to do that. And he said, well, Orly didn’t have the authority to do that either. But, you know, that’s the kind of thing he would do.

[00:15:06] Alisha Searcy: What a fascinating story. Thank you for sharing that. I think it’s a long, winding road. It is, but it speaks to the power of Educators and advisors, many of our listeners are educators themselves and it speaks to the influence and the impact that they can have on the lives of their students.

[00:15:26] Joshua Angrist: You know, my path was turned by at least two points by wonderful teachers. One was that intro econ class and generally I had good teachers at Oberlin. Another important undergraduate teacher, I had a man named Luis Fernandez who was the econometrics teacher at Oberlin. And I got so into econometrics. I kind of outran the curriculum at some point.

[00:15:49] And so Louise just kind of gave me private lessons. He said, you know, read this and we’ll talk about it. And also, I became his ta so as already as an undergrad. So that was wonderful. And then orally changed my life by putting me on the path to being a labor economist, a well-trained labor economist.

[00:16:08] Alisha Searcy: And I’m very interested in digging into that. I want to ask you, just want to go back for a second. You mentioned your time in Israel in the military and your friend Mike. Would you talk about maybe some of the experiences you had and some of the key life lessons that you drew from those experiences?

[00:16:26] Joshua Angrist: You know, the military is not the, I think some people have a romantic view of the military.

[00:16:31] I was challenged in the military, but I’m not sure the military, and I don’t think I was harmed by my service, but I don’t know that I benefited from it except that it gave me this interval to kind of think about what I want to do, and it did challenge me. Physically and spiritually because I was in an elite combat unit, and it was challenging.

[00:16:52] That was my goal. I wanted to be a paratrooper and I was able to do that. But, you know, most people in the army are not doing anything like that. It’s a small minority of soldiers who were in elite combat units. Most of the army is low skilled service trades, and I don’t think you benefit particularly by doing that in the army.

[00:17:11] In fact, the army does that in many cases worse than the civilian sector because it doesn’t have an incentive to value your time. But for me, it was kind of an interval. And then there is the irony that I did my thesis on the effects of compulsory military service. That’s a labor economics question. The American armed forces are the largest single employer of young people.

[00:17:36] Even though we no longer have conscription, that’s still true. Even though we have also a much smaller army than we used to have in the Vietnam era. But there was a big economic debate about whether we should have a draft. Should we have conscription? And even now that question resurfaces. You might have heard people talking about that in the context of the Ukraine war and the conflict in the Middle East.

[00:18:00] And it’s also true that This year and the last couple of years, the military has been, it’s now an all-volunteer force. They’re having a hard time recruiting soldiers. That’s mostly because the civilian economy is very strong. So, people who would ordinarily be tempted to go in the military are getting good jobs and going straight into the labor force.

[00:18:19] But around the time of the Vietnam Wars, America’s involvement in the Vietnam War winding down, beginning in the late 60s, there was a vigorous discussion about whether we should have a draft. And economists were very influential in that. Milton Friedman was one of the leading advocates for a volunteer force, but there were other economists, labor economists, that are less famous, but well known to people like me, like Walter Oyer from Rochester and David Bradford from Princeton.

[00:18:49] And they argued that conscription is essentially draftees. Because there are lots of people who would volunteer for service, and so if you’re forcing somebody in, you’re like taxing them in an amount equal to the difference between what you would have to pay them to get them to volunteer and what you’re actually paying them, which in the days of the draft wasn’t much.

[00:19:11] That must be a large amount because you have to force them, and then later on presumably they don’t benefit from their service because they didn’t want to serve. So that was a kind of a coherent intellectual case for why a volunteer force is better than a draft, but Nobody had really done a good job of estimating the long run consequences of conscription for the men who were conscripted.

[00:19:32] And again, I owe this to Orley. Orley Ashefelder saw an article in the New England Journal of Medicine where some guy’s epidemiologist had compared the death rates of men. who had low and high draft lottery numbers. And the reason that’s important is veterans in general tend to live longer than non-veterans.

[00:19:55] So if you look, for example, at the World War II cohorts, men born in the 1920s, about 80 percent of them served. It was a much bigger mobilization than the Vietnam era. And the men who served who were born between 1925 and 28 lived longer than the men who didn’t serve. So, you might say, oh, that’s because the military is good for you, or there are benefits, etc.

[00:20:17] But an economist looks at that fact and immediately says, that’s probably selection bias. And that’s the way it’s also taught to epidemiologists. The reason that the men who served live longer is that they’re healthier going in. Okay. Because what got you out of service was the was chronic health problems.

[00:20:34] And so that’s not really an effective military service, it’s selection bias, because veteran status is not randomly assigned. And during the Vietnam era, somewhat less visibly, that continues to be true. The military in the 1960s doesn’t take military service. Men with chronic health problems. It also doesn’t take men with low test scores.

[00:20:54] And also among social scientists, it’s well known that the military didn’t take very many African American soldiers at that time, even though black men were trying to get into the army. The army didn’t want people with test scores in the lower half of the distribution and they could screen those people out because they had a draft forcing higher test score men to go in.

[00:21:16] And so you’d like to have an experiment that randomly assigns. Military service to balance all those things out, health and test scores and so on. And beginning in 1970, the order for conscription was determined by random numbers that were assigned to dates of birth. And it’s these numbers that were used in the New England Journal paper to show that military service probably increases mortality, that the men who were forced into service die sooner.

[00:21:48] And the reason we know that is the draft lottery adjusts for that selection bias because the lottery numbers are random. So, people who have low and high numbers are equally likely to have health problems and they have similar test scores and so on. Aschenfelter saw that and he said, oh, that’s such a great idea.

[00:22:06] These epidemiologists had done that for the health, the longevity of the cohorts that were at risk of conscription during the draft lottery. Lottery years from 1970 73 is when we had the lottery. And Orley came into class one day. I was taking his labor class. I took it twice in 1985 and in 1986. And I think it was in the second go round.

[00:22:28] Orley came in one day and he said, I read this amazing paper. These epidemiologists compared the mortality rates, the death rates of men who had low and high draft lottery numbers. And that’s such a cool idea, and they used that difference to estimate the effects of actually serving, being drafted.

[00:22:47] Somebody should do that for their earnings. So, I said immediately to myself, oh, I’m going to do that. And I went right from class to the library. You know, in those days we had libraries, and they had books and journals and things in them. And so I went and I found that article in the New England Journal of Medicine, and I dug into it and tried to understand what they did, and I began to plot my course to what became my thesis, where I got the draft lottery numbers of the relevant birth cohorts and linked that to the earnings data that the Social Security Administration has on all American workers, or almost all American workers.

[00:23:23] And I was able to use that data to show that conscription is bad. It reduces earnings over, you know, a long horizon. Fifteen years later, the men who were drafted earned almost 15 percent. and less as a result of their conscription.

[00:23:38] Alisha Searcy: So, I’m going to break the fourth wall for a minute, just go, you know, right into the next question, but I can’t say that we’ve had the opportunity to talk to many Nobel Prize winners.

[00:23:49] And so we normally for our listeners don’t have video, but I happen to have video right now and I can see the professor. who is not reading anything. This is all off of the top of your head as you essentially read us your thesis in your head. Your brilliance is breathtaking. So thank you for sharing that with us and really helping us to understand, obviously, with all that’s happening in the world and the military and, you know, I’m a little bit younger, so I haven’t, you know, experienced some of these things in terms of military service, but I’m just blown away by just your level of knowledge and how you were able to just go into that. So, thank you.

[00:24:29] Joshua Angrist: Well, well, you know, it’s a story I get to tell often, so that’s one thing you should take into account. Wow. Not the first time I’ve explained it, but I do try to explain it to a general audience.

[00:24:41] Alisha Searcy: Thank you. Very, very informative. And so, speaking of explaining some things to us, you, you obviously have a significant body of work around labor economics and other areas of economics. And so, you have also shifted to do some studying in K-12 education in schools. So, I’m curious if you find that body of work more controversial or about the same, and what drew you into this area of research and scholarship?

[00:25:11] Joshua Angrist: Well, the schools’ question is probably more controversial on average, because most people today are not concerned about, you know, being drafted even though it does come up.

[00:25:22] It’s not likely to happen, and, you know, it’s not a very pressing concern. There’s some interesting economics in that question. Which have broader implications, but it’s not sort of something that people are worrying about in their daily business, the way they worried about where their kids go to go to school and do they have school choice and charter schools, of course, are extremely controversial as you know, and you know, there’s ballot questions about charter schools, but not about the draft, at least not yet.

[00:25:53] So, and I doubt that we’ll see that anytime soon, it becomes controversial when you do work on something like charter schools or vouchers or school choice. It’s a good thing for me and for people like me. We like to work on questions that people care about and that are not just of academic interest.

[00:26:16] I’ve been working on sort of human capital as economists call it, you know, the economic returns to schooling. What’s the link between schooling and wages? I started doing that very early in my career. My first big paper on that was published in 1991, written with Alan Kruger, the late Alan Kruger, who was a great scholar who died a few years ago.

[00:26:38] And we use the fact that compulsory attendance laws affect people differently according to the time of the year that they’re born to construct a compelling natural experiment for how much schooling you get. Basically, if you’re born late in the year, you’ll start school younger because most school districts will let you come in even though say you’re not yet six.

[00:27:01] As of Labor Day, when school starts, and therefore, you, starting school younger, you’re forced to complete more schooling before the compulsory attendance age of 16, say, binds. And Alan and I use that to show that there’s a large causal effect of schooling on wages. But I got interested in the kind of stuff that I think you’re most focused on, and Mike Goldstein is on the chat with us today.

[00:27:26] Partly through Mike, actually. Mike wrote me and Kevin Lang, who’s a labor economist from BU, and a friend, that we should study charter schools. I don’t know, I don’t remember exactly when that was, Mike, maybe 2010 or something? Yeah, 2002. Oh, oh, way older, that’s right, 2003, or 2, or 3, yeah, yeah, so that’s, that’s right.

[00:27:49] And Mike, at the time, was running a school called the Match School. And Mike had somehow figured out that the school had lotteries, and that that would be interesting to somebody like me. The school had admissions lotteries, and we could use the fact that kids are partly randomly assigned to seats in that school, to estimate the causal effects of going to the school, and Mike thought that would be a cool thing to do.

[00:28:13] Rightfully so, and you wrote us, Mike, you wrote Me and Kevin, but then we couldn’t get the data. I remember that being very frustrating. We spent a couple years organizing the, well, we didn’t, it didn’t take years to organize the lotteries. We organized your lottery data that you had for the match cohorts, but then we couldn’t get the state to agree to let us, we wanted to look at the effects of going to the match school on say test scores.

[00:28:40] And we need somebody to give us the test scores, and not just for the matched students. We need everybody in the lottery. So, the state has a test, of course, as we all know, the MCAS, and that would be a great way to measure learning. And we’d have it for everybody in the lottery, or almost everybody in the lottery, but they wouldn’t let us match it.

[00:28:59] At the time, they said it’s not allowed under FERPA, and so on and so forth, that the privacy issues would not allow a scholar. You know, under any circumstances to do that. But then a few years later, or maybe 10 years later, Tom Kane from Harvard kind of broke through that constraint. That was partly through the good offices of Carrie Conaway.

[00:29:22] I don’t know if you know her. She was in charge of research at MassDesi at that time, and Carrie had a social science background and was, like Mike, very interested in this kind of project, and she facilitated that data access. And so, we did our first charter study, which wasn’t actually of the MATCH school in particular, but we looked at a bunch of Boston charters, and we also did a separate study of the first KIPP school in New England, in KIPP Lynn.

[00:29:52] We took advantage of the fact that in Massachusetts, I think it’s part of the state charter law, when the charter has more applicants than seats, they have to use a lottery. They have to randomly offer the seats. And the econometric framework for that question turns out to be virtually identical to the econometric framework that I used to analyze the draft lottery.

[00:30:14] You have something that’s randomly assigned, which is the offer of a seat. But not everybody who’s offered a seat takes it. Some kids who are offered seats. Either their parents move, or they change their minds, often it’s the mom, you know, who wants the kid to go, but the kid doesn’t want to go, so it’s far from certain that if you’re offered a seat, you’ll actually go.

[00:30:33] And then you have some kids who are not offered a seat that eventually get in through various ways. And so, you have something that’s randomized. That’s imperfectly correlated with what you’re interested in. In this case, it’s charter attendance. In my thesis, it was Vietnam era military service. And even though it’s imperfectly correlated, it’s still strongly correlated.

[00:30:52] So there’s an econometric tool called instrumental variables, kind of a class of methods that solve that problem. And soon as I started thinking about the charter school thing, I saw that as a great. application of that method to an important question that was interesting to many people, including me, and I embarked on a whole bunch of research that kind of continues to this day about school effects using the random assignment that’s in the lotteries.

[00:31:20] And since then, we’ve done other things because. You know, the sort of single school lottery is very simple from an econometric point of view, but we also take advantage of the fact that in large urban districts like Boston and New York and Washington and Denver and New Orleans, just in Chicago, just to name a few, you know, many of the largest districts in the country, There’s centralized assignment, and kids get to rank schools, and schools get to prioritize students, and you have kind of district wide choice, but again, many schools are oversubscribed, and so there’s a random number that breaks the ties, and that means that even in a large urban district, where people are making elaborate choices and there’s all sorts of priorities like neighborhood and sibling.

[00:32:04] We can use the random tie breaking in those systems to estimate causal effects. And so that led to a whole bunch of studies, much of which I’ve done with my MIT colleague Parag Pathak and our grad students of school effectiveness of all kinds, not just charters.

[00:32:22] Alisha Searcy: Well, we appreciate Mike for making that call.

[00:32:24] Joshua Angrist: Yeah. Thanks a ton.

[00:32:25] Alisha Searcy: You know, it’s interesting you talk about the number of papers that have been, the research that has been done. And so your research interests include the economics of education and school reform and the labor market, as well as the effects of immigration and econometric methods for program and policy evaluation. I’m a former policymaker. So naturally, I want to know. What do you wish more people or policy makers better understood about K 12 education and labor markets?

[00:32:57] Joshua Angrist: You know, the level of understanding varies, but, you know, there are more sophisticated, less sophisticated policy makers. There’s some policy makers, unfortunately, that probably don’t care much about evidence.

[00:33:09] So at a very basic level, I want policy makers to understand that on many of the issues that they’re concerned with, there is a body of pretty good scholarship on things like vouchers and charter schools. Often the picture that comes out of that is not clear cut. And doesn’t easily fit with a particular ideology.

[00:33:31] But the estimates there are very useful, and they should be a big part, maybe even the foundation of a debate about, you know, for example, lifting the charter cap or, you know, offering voucher options and so on. There’s often a pretty good body of research that can guide that. So, I would like people to turn to that and to seek out.

[00:33:52] The best scholarship, that would be a first thing. The second thing is that a lot of kind of simple, naive analysis is misleading. And my favorite example of that is what I call the Elite Illusion. I give a whole talk called the Elite Illusion. And Elite Illusion is really about the pervasive phenomenon of selection bias.

[00:34:14] It’s about how simple, uncontrolled comparisons that don’t take advantage of something like Charter lotteries or the draft lottery or other econometric tools often present a very misleading picture. And a good example of that is the relationship between selective public schools like Boston Latin School, exam schools, which you have in a bunch of cities.

[00:34:38] You have, you know, in Boston, you have Boston Latin School, which is the oldest high school in the country. In New York, you have the famous Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, Bronx Science, but you also have a very large. It’s a whole sector called the Screen School sector that take kids, you know, unless they pass a test or meet a certain standard of some kind, depends on what it is.

[00:35:00] And Chicago has that, and you have the Thomas Jefferson School in DC and people put a lot of energy into arguing about who gets to go to those schools. And the reason they think that’s important is because if, well, if you look at the graduates of the Boston Latin School or Stuyvesant. In New York, you know, they tend to do very well.

[00:35:21] Some of them even win Nobel prizes and they do better than people who went to say Fenway high school. If we take the Boston Latin school as an example, people who went to the Boston Latin school tend to have higher test scores and are more likely to go to college and. are more likely to go to a four-year college and go to a more selective college than people who went to a traditional public school that’s not an exam school in Boston.

[00:35:46] But again, that’s kind of like the fact about veterans that I told a little while ago, the story I told a little while ago. In our conversation, you know, the reason people who go to the Boston Latin School have good outcomes relative to people who don’t, you know, there’s two possible explanations for that.

[00:36:04] One is that the Boston Latin School is really a superior school. And the people who go there learn more. But another is that it’s selection bias. You only get into the Boston Latin School if you have high test scores and good grades. And that’s baked into the recipe for exam school admissions. And it turns out that once you fix that, and you come up with a good experiment.

[00:36:26] And in this case, the experiment is another econometric tool that’s called a regression discontinuity design, where you have a kind of a test score. It’s not really a test score, but it’s an index that’s a weighted average of GPA and test scores. And you offer seats to people who cross a cutoff, and you can compare people just to the left and just to the right of the cutoff, and they’re very similar.

[00:36:48] That’s the essence of a regression discontinuity design. And when you do that, you see that kids who go to the Boston Latin School have good outcomes, but that’s not because they went to the Boston Latin School, when you have a well-controlled comparison across the cutoff. You see that the Boston Latin School, and I’m just using that as an example of exam schools around the country, they don’t increase college attendance rates, they don’t improve the quality of the college you go to.

[00:37:13] So it’s an illusion, it’s selection bias. And there’s been an awful lot of arguments about who gets to go to exam schools, as I’m sure you guys know. This started during the pandemic when it was difficult to administer the tests and there was a great concern about the racial distribution, the distribution of minority kids among the kids who are offered seats.

[00:37:36] And it is true that black and Hispanic kids are less likely to get into the Boston Latin School or Stuyvesant than are white and Asians. That’s a fact. Maybe that’s a concern, but the consequences of getting into Boston Latin are basically zero. That’s all. And so, why are we arguing about this? That’s kind of our point of view in my lab, that there’s a question of whether this is where the focus should be, who gets into exam schools.

[00:38:01] There are definitely differences in school quality. Our research validates that view. There are better and worse schools, but the schools that people tend to think of as very high quality, in particular exam schools, are not necessarily the best schools. Some of the best schools in Boston, for instance, are the no excuses charters, like MATCH.

[00:38:21] Alisha Searcy: I know someone who knows about MATCH. Thank you for that. And you said a lot in that piece, particularly when you talk about who gets into what schools and why. But I want to ask one more question. I’m going to turn it over to our friend, Mike, who’s co-hosting me today, talking about policy makers. Again, you’ve invented Ingenious ways to measure things. I would love to hear a story in which a policymaker listened to what you figured out, as well as one where maybe a policymaker rejected your evidence.

[00:38:54] Joshua Angrist: I don’t know if I’ve invented, I’ve applied the tools that I use. Pre-date me to, you know, but we came up with good applications in areas that are important to people.

[00:39:05] And in some cases we refined or improved the tools. But anyway, you know, sometimes we don’t set out, we’re not consultants. We try to kind of stay above the fray. We don’t, our mission is not directly to affect policy, but to kind of inform policy. You know, the way we keep score is through the usual academic measures of scholarship and publications and citations.

[00:39:30] But our work does get media attention. You know, we’ve had papers on the front page of the Boston Globe, like the Elite Illusion paper, the first study we did of exam schools. Got a lot of media attention at the time. That was before this sort of recent round of discussions. And I would have liked to see that work get more attention more recently.

[00:39:52] And I tried to draw reporters’ attention to that when I could. But I think if you go back a way, there have been two ballot initiatives related to charter schools. During my time working on this topic, the first one, I think, was in 2010, right, Mike? And the details are a little complicated, but it was about lifting the cap.

[00:40:14] Charter enrollment is capped. And there was a proposal on the ballot to allow schools that are good in some standard to increase their enrollment or open new campuses, because the Charter enrollment is constrained by this rule, and our work on No Excuses Charters in Boston got a lot of attention at that time and probably helped make the case for lifting the cap and that passed, the ballot initiative to lift the cap passed, but then in 2016, there was another initiative To lift the cap, and this one I thought was somewhat more undisciplined.

[00:40:52] So what I liked about the earlier initiative is that it was conditional on good performance. And the 2016 initiative was less structured. So, I was less enthusiastic about it, but Anyway, I thought it was a reasonable thing to do, and again, we had work that was relevant suggesting that many Boston charters were producing very good results, and so a lot of the schools that would be affected would, you know, be high quality schools and all.

[00:41:20] But in the 2016 debate, our work didn’t seem to play as big a role, and the debate was more around the fiscal consequences of charter enrollment, and the opponents argued that charter enrollment takes money away from traditional public students. And we had a study by one of our postdocs showing that that isn’t actually true in Massachusetts.

[00:41:45] It could have been true, but it doesn’t turn out to be true. Camille Terrier, who was a postdoc at the time and is now a professor in the UK, I had a very nice study examining that particular question, and you know, for whatever reason, nobody paid attention to us. And I don’t think this was the only factor, but the ballot initiative failed.

[00:42:05] Alisha Searcy: Thank you. Mike?

[00:42:06] Mike Goldstein: Thanks, Alisha. Josh, it’s so great to hear you. I’m going to ask you a lighter note question. The lighter note is, I’m so curious about Like, what exactly happens when you win something like the Nobel Prize? Like, is there a call? Like, what was the day of reaction? Does your wife say, like, hey, Nobel Prize winner, you still have to take out the trash? Like, what? Tell us a little story about how it all played out.

[00:42:36] Joshua Angrist: Hey, you got to come home. I wasn’t home because there’s all these people in our driveway with microphones and cameras. And I’m here with Nella, who’s our granddaughter. One of the grandchildren usually stays over one night a week and the prize is always announced on the morning of the holiday that used to be called Columbus Day.

[00:42:57] And that’s also like the of the sailing season. I like to sail small boats in Cape Cod, and I had gone down to Get a sail in on the last weekend that you can sail, rent a boat and sail. And I had, you know, gotten up very early for other reasons. And I looked at my phone and I was getting all these texts.

[00:43:17] So I was down on Cape Cod getting all these texts. So, then I had to figure out as This real and so on. So, I called a colleague. I had missed the call from Stockholm, the famous call from Stockholm. I, cause my phone has turned off when I sleep. I didn’t leave it on expecting a call from Sweden. Some people do that, not me. So, then Mira, my wife said, you better get back here. So, I didn’t get to go sailing that day. So, they owe me that.

[00:43:48] Mike Goldstein: And so, you show up at home and somehow the TV.

[00:43:51] Joshua Angrist: Well, there was a lot of reporters there.

[00:43:53] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, and what happens? You get in front of your house, and you say –

[00:43:58] Joshua Angrist: I said a few things, but, you know, it’s not the ideal.

[00:44:01] I hadn’t sort of figured out yet what I wanted to say and do. MIT does a great job managing these things. Yeah. So, you know, the MIT News Office, they’re all over it. They know, they know that the Nobel is going to be announced for each of the fields that MIT has represented in the sciences and economics.

[00:44:19] So they’re kind of ready to go if it happens to an MIT faculty member. So, they give you some guidance and then they actually run a press conference later that morning. So, you have time, you know, to get your thoughts together. So, there’s a video on YouTube of that press conference, if you’re interested. News outlets, you know, ask questions and they manage all that for you. And they give you some guidance about what to do and how to behave. And they field the many messages that come in and they try to figure out what you need to do and what you can ignore.

[00:44:55] Mike Goldstein: And then what? You see if your tux still fits, and then you hop on a plane.

[00:44:59] Joshua Angrist: Well, you know, for the Nobel Prize, you got to, it’s white tie.

[00:45:03] Mike Goldstein: Oh, okay. What does that mean, like the whole, oh, okay, you got to, did you rent?

[00:45:08] Joshua Angrist: Yeah, you rent in Stockholm. You know, I have a tux, but it’s not black tie. The white tie is not something people mostly own. It’s tails, right? It’s the next level up. But anyway, Mike, that year there was no Stockholm thing. Because this is fall of 21. Oh, the COVID is 21, yes.

[00:45:27] So they said, we’re not going to bring everybody to Stockholm. And they hadn’t also in 2020. So, in 22, they brought three cohorts to Stockholm. That’s when I rented the outfit. That was fun. There were three cohorts, which was fun. So, there were more people that I knew.

[00:45:44] And I brought a few of my friends and students along with me, as well as my family. But in the fall of 21, we got our medals in a ceremony in Washington, D. C., which was also nice. It was organized by the Swedish Embassy. They have a great staff there of young diplomats who are super on top of that whole thing.

[00:46:07] And they don’t usually do this, but they definitely stepped up. They hosted a whole series of events over the course of a couple of days. We got the medals from the National Academy of Sciences in Washington. You know, there’s a big, nice building for that. And then we had a nice dinner. And some TV panels and things in, I think it’s called the House of Scandinavia or something.

[00:46:31] It kind of combines a few of the Scandinavian countries’ diplomatic missions and it’s a pretty good facility. It’s got some good, good venues for hundreds of people to sit and catering and all that. So, it was great. We had fun doing that. Another payoff to that was I could have more family, and in particular, my parents who are elderly, they can come to Washington, but not Stockholm. So, they were able to come to Washington. So that was great for that, for them, and for me to have them there.

[00:47:04] Mike Goldstein: What a wonderful thing. And speaking of family, I recall maybe 15 to 20 years ago, your son volunteered at Madison. Carter School, and among other things, he did this combination, as you know, of teaching kids academic stuff, like tutoring, but also how to row a boat on the Charles, and he has since gone on to become a scholar.

[00:47:31] And I’m curious what it’s been like as a parent to sort of have a chip off the old block, in a way, um, as a very original thinker, like yourself, just would love to hear your thoughts on what it’s been like to see your son come up in the same general arena.

[00:47:50] Joshua Angrist: My wife and I are blessed with two wonderful children who make us proud. So, my daughter, who’s the older of the two, teaches at a Boston charter school. Yes. She teaches at UP. And now she teaches at UP Holland. She used to teach at UP Dorchester. And she was in their first cohort of teachers, and so she’s one of the longest running teachers in the UP system. My son went to MIT, and he majored in economics and math, and he got interested, well, he was rowing in high school and he wanted to learn all that, but then he got injured and he couldn’t really row competitively, but he still saw rowing as a good activity.

[00:48:30] And he got the idea, I’m not sure where, that it would be worthwhile kind of starting a student organization that brings kids from Boston schools. to campus and they can use the athletic facilities. Of course, MIT has wonderful facilities. We have a great pool and gym, but we also have these very good crew facilities for people who row competitively.

[00:48:54] They can learn indoors in this sophisticated training setup, and then they can actually go out on the river, which is fun and exciting and requires a fair amount of skill not to do any damage to yourself or your boat. And so They’ll have this great experience, both the physical experience and the discipline of exercise and competitive sports, but also they’re going to have a college facing component where they help kids prepare for the SAT and mix that up.

[00:49:26] The attraction of the athletic activity and the challenge in front of that will get people to engage with the SAT prep and the college prep. And that worked out very well. It turned out to be very popular. And his, he initially was taking kids from Match and O’Brien, one of the exam schools. And since then it’s expanded.

[00:49:46] And Noam developed that with a friend of his and it became one of the largest student organizations at MIT. And it’s ongoing. Still very successful. You know, people, people come to my class, I teach an undergraduate class in econometrics, and they say, oh, do you not know I’m Angrist?

[00:50:07] Uh, I had young woman who’s the head of it. Now, was in my econometrics class, and she asked me if I knew Noam, so that was funny. But, anyway, Noam’s also in the family business, so he did an experiment, because they had more applicants, and they had a kind of a lottery. And he wrote a paper about amphibious achievement, is what it’s called.

[00:50:30] Amphibious Achievement is the organization and the program. And now he runs an NGO based in Botswana. He himself is a, runs a research center at Oxford in the UK. But he mostly lives in Southern Africa in Botswana. And he runs an organization called Youth Impact. And what they do is they look in the academic literature for things that look successful in the domain of partly in public health, now mostly in schooling.

[00:51:01] And they look for interventions that seem to prove themselves as cost effective ways to improve learning outcomes in low-income countries in Africa, but now not just in Africa, also they’re doing in Asia. And then they kind of scale that up and they run their own randomized trial, and they write about that and, you know, get articles out of that in the academic literature.

[00:51:23] But Norm is also a man of action. So, he’s interested in the operational side. So, he also tries to find a way to run these programs sustainably. It’s one thing to sort of do it once and study it and you get a paper out of it, and you move on. It’s another thing to kind of set it up so that it’s sustainable and that the people in charge of the relevant levers, their financial and administrative can actually do the thing.

[00:51:50] Mike Goldstein: Yeah. And Josh, that’s actually such a good point. Let me just double click on that for a second, even though you’re giving it as a specific example. The broader point in economics literature, and I’m curious how you think about this, where an experiment could be set up, find a great effect with very rigorous methods, but then what happens later?

[00:52:15] And you’ve done some work, for example, certainly in the Boston charters, to follow the scaling up. I’m curious, how do you think about this issue? How has it, when you’re looking at other people’s papers, where does your antenna go up a little bit? where you might think, oh, that’s a great result of a tiny program, but I’m not convinced about it at scale. How do you process that?

[00:52:41] Joshua Angrist: Well, that’s sometimes that’s a concern, Mike, but there’s sort of a separation between what Noam does and what I do. I mean, some of what Noam does is also he’s Doing scholarship and writing papers and publishing in journals and so on. But most things, as you know, don’t work out very well.

[00:52:58] You know, there’s a lot of well-intentioned interventions in schools and various efforts to improve outcomes for low income people, whether it’s developing countries or the United States. And it sort of sounds good on paper, but then when you. try it, it doesn’t work. And of course, the education world is full of failed interventions.

[00:53:21] Like most of what has to do with technology is either indifferent, it doesn’t do anything, or it’s bad. So, the scholarship can kind of tell you under the best possible circumstances. Is there any scenario where this is worth doing? And nine times out of ten, the answer is no. Right. It’s not going to be worth doing.

[00:53:43] So you do play this function of kind of ruling out a lot of things that are well intentioned but ultimately ineffective. And, you know, most computer in the classroom type interventions are in that category. And then there are things that are a little more complicated, like charter schools and vouchers, that are more systemic.

[00:54:04] But even there, we see, you know, that not all charter schools are good, and many voucher programs are ineffective or worse. You know, because the vouchers get captured by low quality providers, you know, and that’s under a regime where there’s a fair amount of attention to quality, and then you have to say, well, if I sort of let go of it and just let it run, it’s not likely to do anybody any good.

[00:54:28] Then there’s the question of sustainability, and that has to be addressed, and that’s addressed by people like Noam. So, I see my job as sort of more in the domain of proof of concept. And then there’s also the fact that the world changes, as you know, and we’ve talked about. A lot of the schools that were very successful in our early work don’t seem to be nearly as successful now, and I don’t know why.

[00:54:55] I wish I knew why. We have a big research effort on that, but as you know the pace at which I work, so you know, you’re not going to want to hold your breath for answers, and I’m sure you have lots of insights into this, but we haven’t nailed it.

[00:55:11] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, I, well, I mean, I’m glad you said it. I think it’s such a great thing for listeners of this type of podcast that are genuinely interested in education policy and so forth, and you and I, along with your colleague, Parag, have privately talked about, hey, we, it looks like the impact of charter schools, at least in Boston, have declined in Boston.

[00:55:32] We don’t understand exactly the causal mechanism. We all have ideas. I mean, one of the wonderful things about your work is

[00:55:38] Joshua Angrist: It’s not limited to Boston, by the way.

[00:55:39] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, that’s right. I think it’s a big concern and a topic that I think charter advocates have been trying to wrestle with. And I think one of your obvious Contributions, we can be patient for it is even as a lot of people wrestle with this challenge and, you know, hopefully one day you’ll come along and tell us more dispositively from the data, what you’ve been able with your team to figure out. So, I look forward to that.

[00:56:07] Joshua Angrist: Yeah, we’re definitely on it. And we have a big effort. We got funded generously by the Bloomberg Foundation to work on kind of updating our charter results and expanding. And this is the kind of the, this is the motivating fact that the schools that used to just be so remarkable, some of them are still okay in the sense of boosting some outcomes, but they’re not as good as they were. And also, there’s the evidence for longer term effects is much weaker.

[00:56:36] Mike Goldstein: And I love that, you know, you have such an insider in your daughter, who is obviously doing the work and up everyday teaching, you know, inside of a charter, and you have all different types of qualitative data that flows into your brain.

[00:56:53] I guess one. Place to, and we, Alisha and I are so appreciative of your time today. My final question would be just something, a future thing that you and Parag may be at Blueprint Lab at MIT. What’s one of the questions you’re either tackling now, besides this charter school one, or thinking about, even if you haven’t yet launched the research on it?

[00:57:15] Joshua Angrist: Well, one of our long running programs, which we have been working on, but it’ll still take time, is to get more and better data on longer term outcomes like earnings. And you have to wait a long time.

[00:57:27] Yeah, exactly. So, you have to wait a long time for that, because a kid maybe went to KIPP for 6th grade, and you have to wait for them to grow up.

[00:57:34] and finish school and maybe go to college. And then, you know, so you have to wait 20 plus years for those cohorts to start revealing any labor market effects. And unfortunately, there’s nothing to be done to speed that up. So we have work on that going on in Texas with Jack Mountjoy, who’s based at Chicago Booth.

[00:57:56] Texas has a great data infrastructure that facilitates this kind of work. And we just launched another partnership with our long-standing partner Tom Kane from Harvard to try and do something with Massachusetts. And, you know, hopefully in the next few years we’ll, we’ll have something on that. Besides that, We have, you know, other projects.

[00:58:18] I have lots of other work. Not all of it’s related to schools. Some of it’s methodological. The sort of framework that I operate in, this econometric world of potential outcomes and instrumental variables and regression discontinuity designs, has wide applicability. And so, I’m trying to get interesting, compelling applications in clinical trials such as are used to evaluate medical interventions because I think they’re, you know, we’re sort of, we’re, we’re underused, and we have a lot to offer.

[00:58:56] Mike Goldstein: Yes, you do. I look forward to a lot of what will come out of your lab in the coming years. And again, Alisha and I are so grateful that you, you joined us to share some of your stories today.

[00:59:11] Joshua Angrist: No, thanks. Great talking to you guys.

[00:59:24] Alisha Searcy: Well, Mike, that was an incredibly fascinating interview with a great professor and Nobel Prize winner. Would you agree?

[00:59:33] Mike Goldstein: That was a lot of fun. I’m so glad to have joined you for this.

[00:59:38] Alisha Searcy: Yes, and it was fun to listen to your questions with him because you know him, so you pulled out a lot more than I would have imagined, so thank you for that.

[00:59:46] Mike Goldstein: You bet. I mean, he mentioned a few times a number of different scholars who’ve been generous with their time to him, but he’s been quite generous to me over the years with his time, so it was fun to be on a podcast with him.

[01:00:02] Alisha Searcy: Absolutely. Well, before we go, we have got to do the tweet of the week. It’s from our friend Robin Lake of the 74.

[01:00:11] Mike Goldstein: Robin!

[01:00:11] Alisha Searcy: Yes. And she wrote a piece called, Lessons for Closing Schools. Face the Challenge. Prioritize Students. Just be honest. So, it’s interesting, your article earlier talked about the whole school piece, right? And you also mentioned how in New Jersey, like many other states and school districts, they are facing enrollment issues, under enrollment.

[01:00:35] And so in this article, Robin is talking about how states and districts who are dealing with school closures. You know, there are a number of things that they need to consider. And obviously one of those is, you know, if you are under-enrolled and you have to close, think about the human impact, you know, what it’s going to do to students.

[01:00:54] Think about the funds and not overspending or, Spending resources in places where you don’t need to because for the sake of saving jobs, right, versus harming kids and what they need. And so, this is a great piece in the 74. Highly recommend that everyone reads that, especially if you work in a district.

[01:01:14] And are making decisions around this, lessons for closing schools, face the challenge, prioritize students, and to be honest. So, uh, great piece. Thank you for that, Robin. And so, Mike, thank you again for joining me this week. It has been wonderful. We look forward to having you again. I know you enjoyed it and had a good time.

[01:01:33] Mike Goldstein: Alisha, I very much did. And thanks to our listeners for joining us today.

[01:01:38] Alisha Searcy: Absolutely. And make sure to join us next week. We’re going to have a guest historian, David Heidler, on Andrew Jackson and American democracy. We’ll see you next week.

This week on The Learning Curve, co-hosts Alisha Searcy of DEFR and Mike Goldstein interview Joshua Angrist, the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT. Prof Angrist shares his journey from growing up in Pittsburgh to becoming a Nobel Prize-winning economist. He reflects on his family, formative educational experiences, and his time as a paratrooper in the Israeli Defense Forces, where he gleaned valuable life lessons. Prof. Angrist explores the controversies and his motivations behind studying K-12 education, emphasizing what policymakers often overlook about education and labor markets. He discusses his groundbreaking research on charter schools, highlighting how his findings have influenced policymakers. Angrist also talks about his Nobel-winning work on the analysis of causal relationships in economics and the innovative research currently underway at Blueprint, his lab at MIT.

Stories of the Week: Alisha discussed an article from Independent on the best and worst states for K-12 education; Mike reviewed an article from NJ analyzing Newark’s poor spending habits impacting the success of their charter schools.

Guest:

Joshua Angrist is the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT, a co-founder and director of MIT’s Blueprint Labs, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. A dual U.S. and Israeli citizen, he taught at Harvard and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before coming to MIT in 1996. Angrist received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 2021 (with Co-Laureates Guido Imbens and David Card). He received his B.A. from Oberlin College and completed his Ph.D. in Economics at Princeton.

Joshua Angrist is the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT, a co-founder and director of MIT’s Blueprint Labs, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. A dual U.S. and Israeli citizen, he taught at Harvard and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before coming to MIT in 1996. Angrist received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 2021 (with Co-Laureates Guido Imbens and David Card). He received his B.A. from Oberlin College and completed his Ph.D. in Economics at Princeton.

Tweet of the Week: