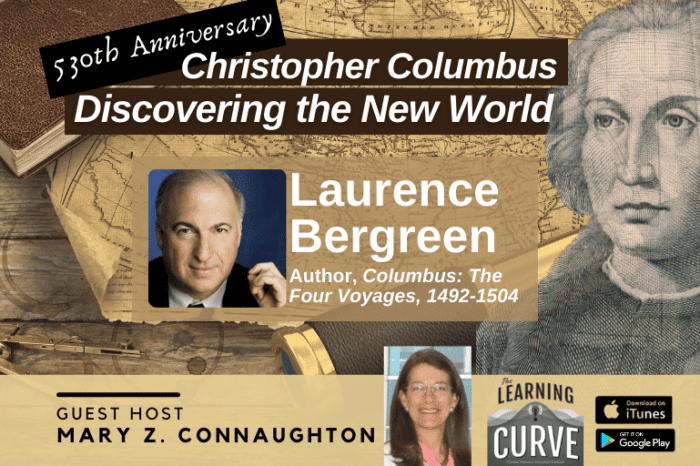

NYT Best Seller Laurence Bergreen on 530th Anniversary of Christopher Columbus Discovering the New World

/in Featured, Podcast, US History /by Editorial StaffOn this special Columbus Day edition of “The Learning Curve,” guest host Pioneer Institute’s Mary Z. Connaughton talks with Laurence Bergreen, a prize-winning biographer, historian, chronicler of exploration, and the author of Columbus: The Four Voyages, 1492-1504. Mr. Bergreen discusses what people should know about the life, career, and myths around Christopher Columbus, the courageous, ruthless, and complicated explorer and navigator, on the 530th anniversary of his history-changing and ever-controversial discovery of the New World. They review questions about Columbus’ background, faith, and education, as well as details about his four voyages’ differing objectives and his mistreatment of the “indios.” They delve into some of the controversies surrounding his legacy, especially his tragic influence on some of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, and the complex political reasons why President Franklin D. Roosevelt made Columbus Day a national holiday in 1937. The interview concludes with Mr. Bergreen’s reading from his Columbus biography.

Guest:

Laurence Bergreen is a prize-winning biographer, historian, and chronicler of exploration. Among his books are biographies of Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo, Ferdinand Magellan, Giacomo Casanova, Louis Armstrong, Al Capone, and Irving Berlin, which have been translated into 25 languages worldwide. Bergreen’s book Columbus: The Four Voyages was a New York Times bestseller, selected for the Book-of-the-Month Club, the History Book Club, and the Military Book Club, and was a New York Times Book Review “Editor’s Choice.” He has written for many national publications including The Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Newsweek, and the Chicago Tribune. Bergreen taught at the New School for Social Research, and served as assistant to the president of the Museum of Television and Radio in New York. He is a member of PEN American Center, and is a trustee of the New York Society Library. He graduated from Harvard in 1972 and lives in New York.

Laurence Bergreen is a prize-winning biographer, historian, and chronicler of exploration. Among his books are biographies of Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo, Ferdinand Magellan, Giacomo Casanova, Louis Armstrong, Al Capone, and Irving Berlin, which have been translated into 25 languages worldwide. Bergreen’s book Columbus: The Four Voyages was a New York Times bestseller, selected for the Book-of-the-Month Club, the History Book Club, and the Military Book Club, and was a New York Times Book Review “Editor’s Choice.” He has written for many national publications including The Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Newsweek, and the Chicago Tribune. Bergreen taught at the New School for Social Research, and served as assistant to the president of the Museum of Television and Radio in New York. He is a member of PEN American Center, and is a trustee of the New York Society Library. He graduated from Harvard in 1972 and lives in New York.

The next episode will air on Weds., October 12th, with Jeff Wetzler, co-founder of Transcend Education, a nonprofit focused on innovation in school design.

The Learning Curve Special Edition Guest Host:

Mary Z. Connaughton, CPA, is Pioneer Institute’s Director of Government Transparency and Chief Operating Officer. Prior to joining Pioneer, she was a partner in the business development firm of Ascentage Group. Her professional experience also includes being an accounting instructor at Framingham State University and senior manager on the audit staff at Ernst and Young in Boston. Mary served on the former Massachusetts Turnpike Authority board of directors. She was a member of the Massachusetts Commission on Judicial Conduct and was on the board of directors of Commonwealth Corporation. She was Chief Financial Officer of the Massachusetts State Lottery and served in the State Treasurer’s Office. Mary was formerly vice chair of the Framingham Finance Committee. Mary earned an M.B.A. from Assumption College in 2009, as well as a B.B.A. in Accounting and a B.A. in English from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Mary Z. Connaughton, CPA, is Pioneer Institute’s Director of Government Transparency and Chief Operating Officer. Prior to joining Pioneer, she was a partner in the business development firm of Ascentage Group. Her professional experience also includes being an accounting instructor at Framingham State University and senior manager on the audit staff at Ernst and Young in Boston. Mary served on the former Massachusetts Turnpike Authority board of directors. She was a member of the Massachusetts Commission on Judicial Conduct and was on the board of directors of Commonwealth Corporation. She was Chief Financial Officer of the Massachusetts State Lottery and served in the State Treasurer’s Office. Mary was formerly vice chair of the Framingham Finance Committee. Mary earned an M.B.A. from Assumption College in 2009, as well as a B.B.A. in Accounting and a B.A. in English from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode

Please excuse typos.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

Welcome to this special Columbus Day episode of the Learning Curve podcast. I’m Mary Carton of Pioneer Institute and I’m guest hosting for Cara and Gerard, who will be back on the regularly scheduled show released on Wednesday. Today is Columbus Day, which marks the anniversary of Christopher Columbus discovering the New World in 1492 until recent decades. It was a national holiday that most Americans celebrated, but it wasn’t controversial. These days, though Columbus is among the most contentious and hotly debated figures in world’s history, as people examine and understand the complexity of his full legacy of expiration discovery, and of course con. For example, a couple of years ago in Boston, a stone statue of Columbus right next to the Italian section of the city was actually decapitated by vandals. There’s no question people have very strong views about Columbus. At Pioneer Institute, we believe in looking unflinchingly at history, especially when it comes to educating school children.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

That’s why we’re providing a special podcast on the topic of Columbus and his legacy in support of a vibrant and robust public discussion, grounded in reason, in facts, we’re so pleased to host perhaps the country’s most preeminent author in biographer of Columbus and other noted explorers. Laurence Bergreen. Laurence Bergreen is a prize-winning biographer, historian, and chronicler of exploration. Among his books are biographies of Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo, Ferdinand Magellan, Giacomo Casanova, Louis Armstrong, Al Capone, and Irving Berlin, which have been translated into 25 languages worldwide. Bergreen’s book, Columbus: The Four Voyages was a New York Times best seller, selected for Book of the Month Club, the history book Club, and the military book Club, and was a New York Times book review editor’s choice. He has written for many national publications, including the Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Newsweek in the Chicago Tribune, Bergreen taught at the New School of Social Research and served as assistant to the president of the Museum of Television in radio in New York.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

He is a member of P E N American Center and is a trustee of the New York Society Library. He graduated from Harvard in 1972 and lives in New York. Lawrence, welcome to the special Columbus Day episode of The Learning Curve podcast. This Columbus Day commemorates the 530th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s History changing in Ever Controversial Discovery of The New World in 1492. Your 2011 book on Columbus is a tour force and was the first major biography of him since Samuel Eliot Morrison’s 1942 book, Admiral of the Ocean Sea. Would you share with our listeners what people should know about the life career myths around this courageous, brilliant, volatile, ruthless and complicated explorer and navigator?

Laurence Bergreen:

Well, I think you broadly hinted at the fact that there’s a lot to him. He’s a controversial figure. There’s a lot to say, but the risk of drastically oversimplifying. As you know, Columbus’s accomplishments are hotly contested today, highly controversial. Even today in the New York Post, they’re saying thatthe Governor of New York is battling with somebody else who’s running for governor about whether to eliminate Columbus Day or not. Anyway, we all know him as the explorer who was the first person to discover America except he didn’t discover America. He never even knew it existed. He sailed to some island in the Caribbean in search of what he called India, which would be our idea of China or the far East, and any people he sought, he found there. And he did find some people, especially the Taino and some others. He considered some form of Chinese and he even brought along a translator with him who was prepared to speak Chinese in the event that he got there.

Laurence Bergreen:

So he was really confused using how could this almost tragically or commonly confused person be considered so important. Nobody had actually shad sailed across the Atlantic before that we knew about successfully, which he did in only 33 days and then sailed back and then did it three more times within the space of 12 years. At the end of that time, Columbus was a broken person. However, the course of history had changed for better and for worse. So yes, he’s very controversial, but also he’s too important and too influential to ignore because of the fact that he broke through this barrier that had existed before. Some of the consequences were tragic, some of them were beneficial. There’s still with us, perhaps now more than ever, and he would’ve been astounded about magnitude and controversy surrounding his reputation because there are hundreds, maybe thousands of places named for Columbus and New York City alone where I live.

Laurence Bergreen:

There’s Columbus Circle and Columbus Avenue and goes on and on and on. Not to mention Columbia University and so forth. And every city or town it seems has its name, honor of Columbus and many of them. And as I said, he never even knew it existed because he never stopped here. He sailed south of the southernmost tip of Florida and was looking for something else. He didn’t know the Pacific Ocean existed that you think, how could he be so challenged? But this was the conventional wisdom in Europe at that time. In fact, the most up to date thinking. So he was actually a person very much of his time and his thoughts about the people who he encountered, which went from at first rather benign to then cruel and exploitative were conventional thinking of his time. He was not an exceptionally cruel or dehumanizing person.

Laurence Bergreen:

He was reflecting attitudes from his native Gena. Oh, that brings up another subject. Where was Columbus born? Where was he from? Well, there are many what they call counterfactual records about Columbus. I used mainly documents that were church records and senses and things like that. So we know really exactly who he was, his family that he was born in Genoa in 1451 while he sailed for Spain. Keep in mind that Italy was not united then. It was a collection of city states, Genoa being one of the most influential. And he grew up as a very successful commercial pilot, you would call it Merchant Marine today. He had a vision which other people shared of being able to sail across the water, across the ocean to this China, which we call the New World. But for Columbus was really the old world because China had existed long before and was in many ways technologically and philosophically and scientifically ahead of the west at that point.

Laurence Bergreen:

So why do we even honor him or remember him? It’s because he was a terrific sailor. He was very courageous. He was very lucky. He would say by the seat of his pants, he read the tides and the clouds and the winds and used his skills for sailing that way. Nobody knew about the existence of the Pacific Ocean at that point, or it was only hinted at he thought it was either nonexistent or very small. So his idea of the world was smaller and simpler than we later found out that it was. But he gave us our first clues. Were there people who had sailed from Europe to the Americas at some point before then, there might have been. There are clues and hints and records that perhaps there were people from Northern Europe or even Scandinavia or some others who had reached Europe before, but they didn’t leave any records.

Laurence Bergreen:

So that’s a very important thing. Columbus recorded a lot about his voyage. It was very well documented. It was very well documented by him, by Spain, by others who went along with him. His son Fernando, wrote and authorized biography of him and he was sailed with Columbus on the fourth voyage when he was a young man. So we have a lot of this firsthand or eyewitness testimony about Columbus. This doesn’t mean that people still don’t come up with various controversies about him and who he was and where he came from. As I was researching this book, I read accounts about the fact that Columbus’s origins were actually Portuguese. While he may have had some Portuguese connection or Polish or some other country or area, but not Gena, many people feel he was a converso Jew who had converted and sailed because the acquisition started about the time of his sailing.

Laurence Bergreen:

That’s not really the case, although there may have been some converso in his crew, including one of his navigators. But so far as we know about Columbus and its family, they were all devout Catholics, Christians, and he later on developed kind of a messianic complex that God wanted him to do this. Did they make these four voyages to bring people who had not previously been Christian into the fold? That’s why he was doing it. Well, there was some also some mixed motives. Often he heard or occasion heard the voice of God speaking to him and you would say, Well, that means, oh, he must have really been crazy psychotic or something like that. However, that was not unusual in his time. Many people heard God speaking to them in various ways. So as I said, he was really representative of his time, although he was very courageous.

Laurence Bergreen:

But he also showed many of the shortfalls or limitations of his era. Also, there were unintentional consequences of his voyage that started during it, but then became even more pronounced afterwards and continued to this day. Alfred Crosby, who was an academic in 1972, identified this as the Columbian exchange. That means a transfer in both directions between two continents, and that included all sorts of livestock, tomatoes and maze. They all went from the Americas to Europe. Before Columbus, there was no tomato sauce in Italian cooking because there were no tomatoes in Italy, there was no chocolate in Switzerland because chocolate had come from the new world to the old and it also went the other way. Horses, stock, pigs, cattle, cats and dogs. They spread from the old world to the new and they transformed the economy there and the society. So the Columbian exchange was subtle, sometimes invisible, but very powerful.

Laurence Bergreen:

There were also some very deadly side effects. Plague and chicken pox and measles and yellow fever came with Columbus and they decimated the indigenous peoples, the Taino and others, the Arawaks who had not developed defenses against them. Tobacco was one of those commodities that transformed the economy. Columbus observed some of the people in the new, what we now call the new world smoking and some sort of tobacco, and he brought some of that back to Europe. That started what became a very important trained and with with a lot of pernicious effects as well, cuz the health hazards of tobacco, which were not recognized at that time. He would’ve been astounded to realize all the things that his four voyages set off. He also would’ve been astounded to realize that he was considered in some way a genocidal figure or monster. But he might have said, you know, there was a little bit of truth to that or some point to it because his voyages unintentionally decimated the peoples of the new world.

Laurence Bergreen:

It wasn’t just the infectious diseases that he brought against, which they had no defense. It was partly in their thinking when they saw his ships coming and his men, that it was the fulfillment of a prophecy of doom, of the end of their tribes, of their lives. When some of the men were beginning to cohabitate with the women, they saw that as also the end and their reaction was not so much to be aggressive but to be suicidal. And many jumped off cliffs to their deaths. Thousands. Columbus was aware of some of this and he was mystified and baffled felt that some reaction or response to his arrival, but it was very, very jarring to him.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

It’s amazing his story and how he still is clearly one of the most important explorers in history. Can you talk a little bit about how he became an explorer and how he became educated in navigation and sailing and also how did he actually secure that commission from the king and team of Spain to find that western route to Asia?

Laurence Bergreen:

He started out as what we would call a merchant, marine merchant semen in and around Gena sailing across the Mediterranean and back. He became very accomplished and skillful. However, there were rumors that it might be possible to sail across the Atlantic to China, Indian Asia, whatever you wanna call it, and that there would be untold riches there. So that’s what inspired him. Others might have tried, we don’t really know too much about it because they perished. The main or most advanced government that was doing it was Portugal and Columbus was there trying along with others to get a commission for years and it didn’t work well. It was rather secretive and perhaps even paranoid just strung him along. So finally he went to King Charles and Carlos, first of Spain, later ever the Holy World empire seeking a commission. He was a foreigner and therefore a figure of some suspicion.

Laurence Bergreen:

But he got the backing from Charles to do it and therefore it was in some ways a Spanish mission. But it was really Spanish genoese kind of a blend. The three ships that we all know about were tiny by our standards. They were carves, which were a kind of hybrid design of Arab and European ships. And if you boarded one, we would say, How is it possible to sail across the Atlantic with his storms and survive? But Columbus was a wonderful intuitive sailor and made this crossings the first time and and 33 days, his later crossings were equally efficient. So getting there actually was the easy part, <laugh>, it’s what happened afterwards that became so difficult. He kind of gave his life to this endeavor. At the end of the fourth voyage, he was broken in health, he was kind of out of his mind and returned to Europe basically to die.

Laurence Bergreen:

He was almost half dead on the second part of the voyage. Anyway, you know, as I said, he was driven by this kind of messianic fervor and he never really knew where things were though. That was the terrible irony and also some of the ill effects that he set off. But he didn’t realize what he was doing or where he was going or where this would lead. But that’s actually discovery in a way. I remember once going to a conference at Nasa for a Mars mission and one of the scientists who was in charge of the exploration part of it was asked by the press, What do you plan to discover on this mission? And she said, Well, if we knew what we were gonna find, it wouldn’t be a discovery.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

Columbus once wrote, I saw several things that were indications of land. A large flock of seabirds flew overhead. How did he actually go about recording his explorations on those four voyages? And his first voyage was a successful journey into the unknown. How did his recordings change over the course of the other three voyages?

Laurence Bergreen:

He kept logs and so did others on the voyage. Whether he wrote them in real time as it was happening or that night or in recollection a week or even years later. It’s not really clear, but they generally are accurate because they agree with other accounts about when things happened and what the events were. And the more he wrote, the more articulate he became. Of course it was sort of special pleaing for his own success or his fears or his own idea of what being a hero meant. So he wanted to leave a record. He was very conscious in that of what he had done so that he would be remembered. And his son Fernando, took up that cause and also wrote a lot about his father and preserved, became a bilio file, had amassed a rather large library. So he also preserved the Columbus reputation.

Laurence Bergreen:

However, the whole idea, long distance exploration across the Atlantic languished for years until Mitchel came along, which was almost 60 years later, nobody else attempted anything like that. And Magellan of course went much, much further than Columbus ultimately met with a tragic end, but demonstrated a lot of things which Columbus didn’t even guess at the fact that the Pacific was huge, that it water covered two thirds of the Earth’s surface, more or less how big the earth was, that it was beyond questioned round. The sailors knew this and many people knew this all along. It was not really a surprise. All you had to do was stand shore and watch a ship slip the hole, the horizon as it sailed away and you realized it was round. So, and of course the res and Robins realized the same thing. So the idea of a flat earth was overplayed and Columbus was certainly not a flat Earth Earth, but he percept about the cosmos and about Earth at that point. But we learned from his mistakes.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

Of course, the most controversial part of Columbus’s legacy, I say, remains his relationship with the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. And you touched on this earlier, but could you talk a little more about the seeming tropical paradise he found in 1492 in his relationship and interactions with the various tribes he encountered, including the enslavement massacre in the disease that fell upon the taes?

Laurence Bergreen:

Yes, let me just say he did not set out on a mission to slaughter indigenous peoples, the TA and the ax and others he set out to go and to trade with. He called Indians after India in China. When he encountered these indigenous people at first he admired them. They seemed very capable, elegant, and capable of mariners. Later on, slavery was common in Italy. At his time in in gen, you can see from his records, he began thinking, oh some of them might make good slaves. That was not part of his mission to go and find slaves, but it occurred to him. So he wound up having mixed motives partly to convert them if he could, to Christianity and partly to exploit them. And yes, it was all confused, but that was a confusion that he reflected. I don’t know the Western European psyche at that point. He was, as I said, not an aberration. He kind of was characteristic of all that and it was just a different era. It’s hard to judge explores of that era, our standards because with Miss a lot, and that’s not to excuse them at all, but if you wonder what they were thinking, you really have to read their own accounts to understand what they were thinking. And it’s different from the way we think.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

Finally, even though Columbus never set foot in North America, as you’ve mentioned, he was celebrated in a famous early 19th century biography by Washington Irving in poems by Walt Whitman in in 1937, President Franklin d Roosevelt made Columbus Day a national holiday. How should the public teachers and students alike use the knowledge of history, warts and all to better understand Columbus and his complex legacy?

Laurence Bergreen:

Well, I think he’s particularly complex because he’s many faceted and it’s hard to come down with a simple judgment on him. I think the understanding of Columbus and its evolution over the centuries and even in the past 50 years is really a dramatic case study of how we view them. When, when I was a kid in school, Columbus was seen as a hero figure and there was Columbus Day and it was holiday and great, but it’s a relatively recent phenomenon. FDR instituted made Columbus Day, a federal holiday in 1937, partly to appeal to one of his constituencies that was Italian Americans. So there was a political angle to it. There had been parades and Otter of Columbus for decades prior to that. So in a sense he was just making this official, but that was part of it. Also, he wanted to give a sense of inclusiveness.

Laurence Bergreen:

Now, in some ways it boomerang or backfired because as time went on, there was, and we are more understanding of what the consequences of Columbus’s voyages were. It backfired and we see that the legacy was very troubling and not absolute scary because of his treatment of indigenous peoples. Of all, some of it or a lot of it was not intentional, perhaps some of it was. And his biographers, you mentioned Samuel Elliot Morrison, who was perhaps his first modern biographer Morrison was a legendary historian, a biographer at Harvard. And his biography, which was written keep in mind during World War ii, during a Patreon era, tended to emphasize the positive part of Columbus. He acknowledged it cuz Morrison was very smart and this was very, very thorough biography. He acknowledged some of Columbus’s shortcomings but kind of glossed over them and also the technology that was available to him.

Laurence Bergreen:

We didn’t quite get that fuller picture of what Columbus did or where he went. Now there’s a lot more documents that are available. There’s a lot more ways to get out the truth of what happened to Columbus and data from satellites and remote sensing and things like that. So we have a much more accurate or scientific understanding of Columbus and shortcomings. So Morrison was certainly the state of the art of this time, but we’ve slowly moved on. I tried to give a sense of this varied kaleidoscopic view of Columbus, and he’s not the only historical figure who’s undergone a reevaluation. There are certainly others throughout history. Lots of legends have spun up about them. Columbus is only one of many, and people project a lot of things onto them, which aren’t necessarily relevant to what was going on at the time, or to see him in their own image or in one way or another.

Laurence Bergreen:

He’s a fascinating case history, but we’re lucky because we have so many primary documents about him. So we can see Columbus in his own words front and the records of other people, the Spanish kept very detailed records about his voyages. There’s a lot of things that we can put together to get a modern view of what Columbus was like. And you know, what emerges often is how misguided or diluted he was in terms of thinking about where he was or where he was going. It’s kind of extraordinary. Imagine if he driving across the United States and you reached Kansas City and he said, Okay, now we’re in la we’ve come to the end of our voyage. That’s to give you a rough idea of how confused Columbus was and yet he was doing a better job than anybody else at that time.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

That’s remarkable. And that’s a great analogy. Is there a brief paragraph from your Columbus biography you’d like to read to close out the interview?

Laurence Bergreen:

Sure. This is from my book, sort of the general description about Columbus is just a couple paragraphs to the end of his days. Columbus remained convinced that he sailed for and eventually arrived at the outskirts of Asia. His unshakeable, Asian delusion motivated his entire subsequent career in exploration. No comparable figure in the Asia discovery was so mistaken as to his whereabouts. Had Columbus been the one to name his discovery. He might have called it Asia rather than America. Obsessed with his God given task of finding Asia. Columbus undertook four voyages within the span of a decade, each very different, each desire to demonstrate that he could sail to China or Asia within a matter of weeks and convert those he found there to Christianity. But as the voyages grew with complexity and sophistication, and as Columbus failed to reconcile his often violent experiences as a captain in provincial governor with the demands of his faith, he became progressively less rational and more extreme until it seemed as if he lived in his glorious illusions rather than in the grueling reality to his voyages laid bare. If the first voyage illustrates the reward of exploration, the subsequent three voyages illustrate the costs, political, moral, and economic.

Mary Z. Connaughton:

Thank you for joining us. This has been an interesting and engaging discussion that we hope has been helpful as people are trying to make sense of these public controversies and learn more about Christopher Columbus and our shared history. Please tune into our regular podcast of The Learning Curve on Wednesday with Cara and Gerard.

Recent Episodes

Cara and Gerard on Their Time with The Learning Curve

Becket Fund’s Eric Rassbach on Religious Liberty & American Schooling

PRI’s Lance Izumi on Charter Schools & School Choice

McGill Prof. Marc Raboy on Guglielmo Marconi & Global Communications

Donald Graham on The Washington Post, Media, and Educating Immigrants

Columbia Law’s Philip Hamburger on Church, State, & School Choice

AEI’s Dr. Diana Schaub on the Founders, Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, & Civics

Morehouse’s Prof. Marisela Martinez-Cola on Pre-Brown Cases for Educational Equality

Marquette’s Dr. Howard Fuller on School Choice, Charter Schools, and Race

Columbia’s Pulitzer Winner Prof. Eric Foner on Lincoln, Slavery, & Reconstruction

Fmr. Mississippi Chief Dr. Carey Wright on State Leadership & NAEP Gains

U-Hong Kong Prof. Frank Dikötter on China: Mao’s Tyranny to Rising Superpower