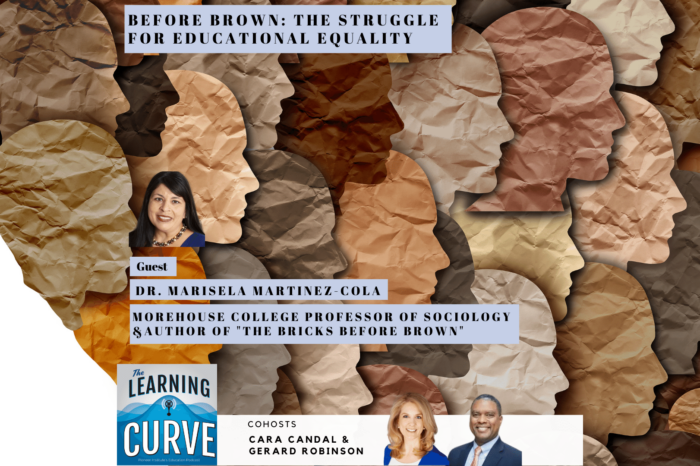

Morehouse’s Prof. Marisela Martinez-Cola on Pre-Brown Cases for Educational Equality

/in Civil Rights Education, Featured, Podcast /by Editorial StaffThis week on The Learning Curve, Cara and Gerard speak with Morehouse College’s Dr. Marisela Martinez-Cola, JD, about her book The Bricks before Brown: The Chinese American, Native American, and Mexican Americans’ Struggle for Educational Equality, on the long struggle for equal opportunity in American education. She discussed the many cases that preceded Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 decision that overturned the doctrine of “separate but equal” established in the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. Dr. Martinez-Cola reviews the important, lesser-known legal challenges brought by Chinese American, Native American, and Mexican American plaintiffs, and how their efforts set the stage for Brown and continue to shape Americans’ understanding of civil rights and equality of educational opportunity.

Stories of the Week: Cara discussed an Associated Press story about Teacher Appreciation Week that reports on retirements, shortages, and overwork among teachers. Gerard talked about an Education Week story, “History Achievement Falls to 1990s Levels on NAEP,” detailing the sharp decline in eighth graders’ scores in U.S. history and civics assessments.

Guest

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a transcript here:

The Learning Curve transcript

Dr. Marisela Martinez-Cola

Cara: [00:00:00] Learning curve listeners, it is Cara Candal and I’m so happy to be back with all of you and with my partner in, is it crime? I don’t think we commit crimes. We’re pretty upstanding citizens. My partner in pod. How about that? Fantastic. Yeah, I like that Gerard Robinson, how you doing?

GR: It’s, first of all, I’m fine and it’s good to be back together again with you. It’s been a few weeks. It’s been a few weeks.

Cara: It’s been a few weeks now. Okay, so speaking of [00:01:00] weeks, Gerard, you know that this is a special week, but I wanna, I wanna lure you in by asking you, are you feeling appreciated in your work, in your life, Gerard, do you feel appreciated?

GR: I feel appreciated, but not as much as the people who woke up this morning and are now sitting in class rooms all across America.

They should be appreciated really well this week. But I still have appreciation cause I’m getting my student evaluations in. Oh, and I’m seeing some good things.

Cara: so, oh, well that, that’s encouraging. I love that. I love that very much. I wanna talk about the concept of teacher appreciation because one of my friends pushed me a tweet.

Uh, We’ll see if she’s listening. That said like, you only need appreciation weeks for underpaid professions sort of a thing. And I thought, yeah, okay. We’ve heard that one before and it may or may not be true, but you and I both think a ton about teachers. I’ve been thinking a lot about it lately, [00:02:00] and I was thinking about my own kids’ school.

Interestingly, my kids’ school celebrated teacher appreciation week like two weeks ago, and I think that they do. Nice things. You know, they do the kids made cards and parents of course donate so that there’s lunch in the community room every week. And I did hear teachers. You know, when I was in the school, not just saying thank you, but saying like, oh, I’m so glad it’s Teacher Appreciation Week because we get this good food.

which is lovely. But I think that you know, this point that my colleague made about, we use teacher Appreciation week or we give people things when maybe they could make a little bit more money. And this pertains Gerard. To my story of the week, which comes from the Associated Press And, hang on, I’m just bringing it up here.

Maybe you can hear me. I wanna take a look at it. And the title of this is, teachers Earned $67,000 a Year on Average. I’m gonna say that’s higher than I thought it was. It’s. Still, if [00:03:00] you think about it, depending on where you live you know, doesn’t rival a lot of other professions, but the Title six, they make 67 K on average, is the push for raises too late.

And this is by Mark Levy. So Gerard, if you’ve been watching, and for others that have been watching, We have absolutely seen a good number of states make moves recently to increase teacher pay. So basically what they’re doing is they’re increasing the floor saying you can’t pay teachers less than X. And I think in large part, you know, it’s a necessary thing.

I also think it can be insufficient and makes policy makers and legislators maybe feel like they’re doing enough and they did a good thing. When you break it down as somebody interviewed for this article points out. A lot of the time, that extra little boost, so say you raise the floor from teachers can only make, you know, $67,000 a year, but we’re gonna call it 70.

If you’re already making that, that increase in your paycheck after taxes certainly doesn’t feel like a [00:04:00] lot. And the other thing is that this article echoed something that I think. You and I probably are familiar with because we’ve both not only studied, but worked in, in certain case, at certain times in our lives in private schools, or at least I have, I’m not sure if you’ve ever taught in private school.

And what a lot of people fail to realize. I. Is that teachers in private schools, I think on average make even less money than teachers in public schools, a lot of times you have private schools probably could be unionized, but aren’t there’s a lot of reasons for it and they have different sort of approaches to pay in many cases.

But read the research, a lot of private school teachers report. A willingness to stay in their jobs. They have higher rates of retention, in part because they cite the work culture as being a place that satisfies them. So that could be for some people that they’re really bought into a specific mission or vision of a private school.

But it could also be that some schools just really create a good culture in which to work and that people would rather have that than [00:05:00] salary. And let’s be clear. Private schools also offer other perks, like perhaps tuition remission if you wanna send your own kids to that private school. , among other things maybe more flexible working hours.

They might have more autonomy to do certain things, but it occurred to me as I was reading this article, and I think the article does a pretty good job of bringing that up, that as we talk about. This, you know, scare around teacher shortages. And to be clear teacher shortages are very targeted in this nation.

They are not everywhere. They are not in every aspect of education, but they’re there. And as we talk about teacher shortages, I think we need to have a broader conversation than just let’s up teacher pay. That should certainly be a starting point. That should be part of the conversation. But we also need to talk about work culture and how we support teachers.

And there are a couple ways to do that. I’ll go back to the finances for a minute though too, because if we’re gonna increase teacher pay, we should probably also talk not just about loan forgiveness, but about actually forgiving loans upfront or making teacher training programs free, which is something that I think [00:06:00] states need to really put some skin in the game on to be able to do, especially as we talk about growing more robust teacher pipelines.

But there are other things. That they can do too. And that’s things that teachers cite. I think we’ve discussed this research on this very podcast, more support staff in classrooms so that they feel like they can spend more time individually with kids, et cetera. And just, you know, I think appreciation is part of it, but feeling like you can be effective in your job and that involves, Working in a place where you have people surrounding you that help you to be effective in your job.

I’m sure those of us who are happy in our jobs, I have to say, I’m one of those people, feels that I have people around me who help me to be really effective. So, all to say, Gerard, now I’m gonna go a little doomsday here. need to talk about this in the context. Of course, as I said, ad nauseum on this show in recent weeks, looming fiscal cliffs for many districts.

So, As those ESSA funds are expire, and most of ’em are gonna be spent [00:07:00] down in 2024, a lot of districts are gonna have to make hard decisions about what to cut. And even if they’re not cutting teachers, they might be cutting those folks, those people, those programs, those things that make teachers lives and work culture sustainable or more sustainable in some places, I could say.

And a lot of teachers that you talk to, and certainly some teachers quoted in this article, say that those things are more important. Then the extra 500 bucks they might see in their paychecks after taxes once they get the pay raise from the legislature. So during this teacher appreciation week, Gerard, I hope that we can encourage our listeners to think about not just, you know, showing those teachers in your life a little love, but how we as a society think about supporting the people who are caring for and educating our kids.

Every single day, no matter what school they are in. So as you look at your evaluations roll in, and hopefully you’re able to give yourself a, a much deserved pat on the [00:08:00] Backard, I wonder what you’re thinking about the other teachers in your lives and the policies we create that affect them.

GR: Let me say, sister Teresa was my.

Fourth grade school teacher, she’s still alive. I had a chance to see her when I went to California. A friend of mine, in fact, had a chance to see her the other day. I wanna say I appreciate her. I wanna say I appreciate the teachers for all of my daughters who went to a mix of public schools and private schools.

And I wanna say a thank you to all the teachers in Charlottesville, Virginia, where I live. Both. Private, public, those who are not working in pods and otherwise. So just trying to give the home team some love. Everything you said, I’m pretty much in agreement with you said one thing that I really had not thought about making teacher preparation free.

I actually had never thought about that. That actually may be something that Deans of education state boards of education, the accrediting [00:09:00] agencies may have to think about. Because between the number of people I know who are leaving the profession within the next three years burnout is one big factor.

Retirement. And then third is just, just doesn’t feel the same. And coupled with so fewer students, Majoring in education or going to the profession, we have to find something different. So, That’s actually something we should noodle to lower. So that’s, that’s a really good idea. And in terms of pay, yeah, we’ve talked about that on the show.

Some cities are, are doing better jobs than others. And often when I would find myself in a position of someone saying, you know, you don’t pay me enough I’d have to remind educators that your local school board and your superintendent for the most part set your, pay scale. And there’s some things that we can do.

But we should also say in terms of teacher appreciation week Karen and I are working on a policy brief that is a step in the right direction toward putting more finances into the pockets of teachers, but also in building the infrastructure of schools for [00:10:00] the long term so that no matter who’s in the classroom or who’s in the principal’s office, there’s a pot of money set aside to invest into teachers, particularly those in the STEM area.

Cara: Yeah, that’ll be coming out soon. We’ll, we’ll let everybody know when it’s released, right Jar?

GR: Yep, sure will. Amazing. All right. My story is a little different, although of course it involves teachers and this is about Nate and the scores in civics and history. Now, of course, I’m not going to do a repeat in seeing the theme or a saying from the Gomer pilot show.

I did that for Nate. When we discussed scores from last year, so I’m not gonna do that again, but as we knew there would be a drop in Nathan Civic scores, partly because of Covid, partly because of other dynamics. But I think what really moved people is just how much. This plays in with what we’ve been talking about for like 25 years now.

So my story is from [00:11:00] Sarah Schwartz Education Week, and his titled History Achievement falls to 1990s, levels on NAEP Civic Scores Take First Ever Dive. So from a national overview there. Was a nationally representative sample of 800 8th grade students who took the history test, and 780 8th grade students who took the civics test.

And that’s worth mentioning because some of our listeners may not know that Nate isn’t a required test for every single child in every single state. Who is in eighth grade? It’s a national representative sample, both public, private, and charter. So we’ve got that. And when we take a look at the scores there were a couple of points that people said we should really look at.

So let’s take for example, the NA score for six. In 2022, the average score was 150. And I mentioned 2022 because that’s when students in the spring of that year took the test. The average score was one 50. [00:12:00] In 2018, it was 1 53. In 2014 it was 1 54. So we’re seeing a decrease, and in fact, the one 50 score for 2022 is the exact same score we have for.

Civics in 1998. History wasn’t as bad, but wasn’t great. And so if we take a look at the history average score for 2022, it was 258 and 20 18, 2 63, and in 20 14, 2 67. So also on a downward trend just not as high for both civics. And for history the achievement, the advanced cut score, our scores were way below that.

In fact, our scores for Nate history and for. The achievements made proficient in civics. Both were below what we thought was proficient, so we know that that is what we have. So we now have to listen to people who we know and listen [00:13:00] to, to figure out what happened. And so according to people who looked at the re results, they said that other students who took the exam in 2022, 68% said they had taken a class focused mainly on US history by grade eight.

A significant decrease from 72% in 2018, and 49% said they had taken the course, mainly focused on civics, which represents no change from the previous year. Now, Peggy Carr, who is the commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics said that in. A briefing that she gave to reporters.

She said, what we’ve learned in these subjects is part of the fabric of who we are as Americans, and they’re essential subjects. And she says, if you wanna know what matters, Course taking matters. She says, we were seeing particularly that students who took courses in US History and students who took these courses on average do better than those who do not take courses in history.[00:14:00]

Well, we also go to another colleague in the work, Kelly Stanner. She’s Chief Living Officer for the National Constitutional Center, and they provide resources and lessons to teachers about the constitution. She said that great civics isn’t just memorizing facts or dates, but it builds upon skills that allow students to discuss, to debate and build consensus.

And she noted that only seven states in the country actually require civics in middle school. Now that number is probably much smaller. Then our listeners would think, so I want to put this in context. And so what I decided to do was to go to the education commission of the States. They had a 2016 report where they did a 50 state survey of civics in the us and they identified that 47 states in DC addressed civics in state statute.

And they also provided a few states to do some interesting things. For example, Rhode Island and Tennessee they actually established the purpose and goals of. Civics and civic [00:15:00] education in state law. Pennsylvania not only identifies what students must learn, but they put it in the context of, of an obligation to exercise intelligently their voting privilege, and they provide other states.

I’m happy to say that Virginia is one of the seven states that has at least half a year of civics. We also do it at the high school level Massachusetts, I know where you are. They also have it in the middle schools as well. So I agree with Peggy that course taking matters. And so that’s something states could look at.

And Virginia in our own state we just went through our history standards and Carrie is also correct that we’ve gotta build skills not based upon memorization. But moving students to think, but we also can’t act as if we just arrived to this problem. In 2014, the Pioneer Institute released a report which identified civics not only in Massachusetts, but across the board.

And even then they said, we’ve gotta do a better job of getting students prepared for this. So for the Pioneer Institute they saw this [00:16:00] coming for a long time and it provided. Several recommendations on how to handle it. As you know, when I see the scores, I try to put it in perspective. I think it’s important, it’s a good guardrail.

But the one thing I wanna make sure we don’t do is to say that the drop that we’ve seen in both history and in civics, Is due solely to the pandemic or solely to culture wars because in the article Sarah rightly brought up the number of states who’ve passed laws to cartel where teachers can say or teach, which I think is problematic.

We’ll say that for another show, but there is definitely that dynamic too. But let’s remember we had 150 achievement score in 1998. When we didn’t have Coach Wars like this and when we weren’t banning books particularly books authored by or about black culture, same in 2006, 2010, 2014, 2018, and the same to history.

So while those things play a role, I hope we just don’t anchor the challenge and problem [00:17:00] to the last three years. We’ve gotta see this as a. 30 year dynamic, possibly even a 40 year dynamic sensation at risk turned 40 years old last month. And as they said then, if the educational requirements or the educational outcomes that we see right now in our nation were placed upon us by a foreigner country, we would see it as a declaration of war.

What are your thoughts?

Cara: Hostile foreign power. Those are hard words to forget. No, I, listen, I, I would applaud the notion that we can’t blame this on the culture wars of today or even the culture wars of yesterday or, what’s been going on politically in this country. and one of the things I worry about Gerard is as we.

Consider the things that kids now need to know, people now need to know to be successful post-secondary in whatever sort of path they choose. Things like history and civics could increasingly be pushed out even more.[00:18:00] I also think it’s a great idea when states say you have to teach this. I wonder about the extent to which we really hold folks accountable for teaching it or for teaching it.

Well, right. Because I don’t think that those things get measured very well, except maybe on na and we see where that’s going. I’m, I’m worried of laws that sort of quantify you need 30 minutes or one semester. Right. I think that it should be more about Also thinking through how we integrate these standards for learning into everyday work into the kind of writing and thinking and being, the kids need to be able to do that, students need to graduate with.

And if we can get to a place, and in some schools that is happening, obviously some schools are very focused on that kind of stuff. But if we can get to a place where, We’re not afraid of talking about civics. We’re not afraid of teaching it, and we value it as so many of the guests that we’ve had on this show speak to its value.

Then maybe as we consider what the next generation needs to know to be successful [00:19:00] in life, this will remain a part of it. But I think that those name scores are an indicator that not too many people. The value what civics and history education have to offer. I cannot even tell you. I do not remember if I had any sort of civics education.

I think, I know I had a government teacher, so I’m assuming there was some civics in there. But. Yeah, I guess that’s civics, but I don’t know if it taught me to be civil. I don’t know. Gerard,

Cara: we’ve got a wonderful guest waiting in the wings. We are gonna bring on listeners in just a moment.

Dr. Mariella Martinez. That’s me trying to. Speak my Argentine Spanish right is a little bit annoying. Dr. Mariella Martinez Cola jd. She is the assistant professor of sociology at Morehouse College and the author of The Bricks Before Brown, the Chinese-American, native American, and Mexican Americans’ Struggle for Educational Quality.

I am looking forward to this, so we’ll be back right after this.[00:20:00]

Learning Curve listeners, as promised, we are back with Dr. Mariella Martinez. She’s an assistant professor in the sociology department at Morehouse College and is a proud Chicana daughter of an immigrant and a first-generation scholar. For nearly a decade, she worked in student affairs at Davenport University, George Washington University and University of Georgia, and then three years in an academic position at Utah State University.

Dr. Martinez-Cola has published the book, the Bricks Before Brown, the Chinese American, Native American, and Mexican Americans Struggle for Educational Equality [00:21:00] where she identifies over 100 cases filed before. The famed Brown V Board of Education. She earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology and African American studies at the University of Michigan.

Go blue. I am from the Ann Arbor area and she has a law degree from Loyola University, Chicago School of Law, and a PhD in sociology from Emory University. Dr. Martinez, welcome to the Learning Curve.

Marisela: Thank you so much for having me. I truly appreciate the opportunity to be able to talk about something I love so much.

Cara: Yeah. Well, I have to tell you, I am so excited in my own dissertation in my four education policy studies. Boy, oh boy. You know, I talked a lot about Brown View Board of Education and it impacts that it’s legacy on what we know is education today. And I don’t think I know. Much at all about the content that you have brought to us in this book.

So tell us a bit [00:22:00] about the Bricks before Brown. I’ll just if you could set the stage and give us sort of the basic facts of the 1896 US Supreme Court, Plessy Ferguson decision, as well as the legal background, just so our listeners sort of are unequal footing here. and then talk to us about the basic facts that you bring to this book.

Marisela: this book was a labor of love. And so what I thought about, having gone to law school, of course I was first in. Brownie board. And that’s in every constitutional law class that you know, you take. And interestingly enough, even as a professor, my international students even have heard about Brownie board, right.

And so I kind of considered that the sort of the, bookmark, you know, the bookend. I called 1896 Plessy versus Ferguson, the other bookend, right? And then Plessy versus Ferguson. This was where the Doctrine of Separate but Equal was actually created as a result of a gentleman named [00:23:00] Homer Plessy, who did not want to give up his seat, his seat to a white man and go into the black car of a railroad station.

And so, What ended up happening there, and I’m don’t mean to oversimplify this, but that’s really where the doctrine came about of separate but equal. And so I thought what happened between 1896 and 1954? Because I know that law builds on cases. It doesn’t just all of a sudden happen. Brown didn’t just suddenly happen, you know?

There had to been some wonderful history that came before it. And so as I started to do research, I realized that it came even before Plessy versus Ferguson, and that this battle actually started in 1849 in Robert C Boston in Massachusetts.

Cara: Wow. Right here where I, in my backyard. I wanna pick up on your discussion of Plessy v Ferguson.

And of course there was only one dissenter from the majority opinion, only one [00:24:00] dissenter in that case. And that was Justice John Marshall Harlan. And said, quote, the judgment this day rendered will in time prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the dreads.

Scott Case. So could you talk a bit about that dissent and its origins in the

Marisela: 13th Amendment? Yeah, absolutely. So Justice Harlan it was interesting because when you look at the opinion, it’s actually a very lengthy dissent, particularly compared to the relatively short majority opinion. that’s fair.

And so, What had happened before Plessy occurred and, and this is after the Civil War, there was this era called reconstruction. And then during that time, the amendment, the 13th amendment passed, which is which abolished slavery, the 14th Amendment passed, which ensured birthright citizenship and had equal protection and the 15th amendment pass, which creates the right for the formerly in place to vote.

Right? So there was a lot of really amazing things happening, you know, at the time. There were [00:25:00] also however, laws and practices that were trying to go against what all these new rights for all these new rights that were coming along. And so justice Harlan actually did not support the 13th Amendment initially.

But then in the came, came around to it. And this is really interesting. He was born into a Kentucky slaveholding family, right? But eventually he came around and he believed that the reconstruction amendments were critical to the us. And so what he was talking about when he talked about Fred Scott is that there are certain.

Sort of touchpoints in our legal history where really bad decisions were made. And in dread Scott, basically to be able to take away citizenship rights for African Americans in the US and not to be considered a, a full person personhood. And so what Justin Harlan was really saying is that just like we were on the wrong side of history, then we’re on the wrong [00:26:00] side of history today.

And. What was so amazing about his dissent is it actually ended up being used in Brown V Board. Justice Warren used it all these years later in 1954. and

Cara: then of course we think of Brown. V board in so many ways as the writing of this great historical wrong took a very long time to get there.

And certainly at first, folks didn’t want to listen to the Supreme Court decision and there’s. I’m sure many, many shows that we could do on that. But just to continue to set the states for our listeners, before I hand it over to Gerard to really dig into your own work, talk to us about exactly what Brown V Board of Education brought, because it really only partially overturned p v Ferguson.

So give give us a summary and, I’m so curious to know, like how we connect this all to the, basically the prelude to Brown that you

Marisela: have uncovered. [00:27:00] Brownie Board is an interesting case. A lot of people know the 1954 Brown v. board. They don’t know that a year later another opinion was written.

So you’ll often see it referred to as Brown one and Brown two. Brownie board was actually also one of five consolidated cases involving school desegregation. The other cases were Bridge v Elliot, South Carolina, Davis e country School Board of Prince Edward County in Virginia. Belton and Delaware and balding, v Sharp, Washington, dc And so I think it’s really important to understand how strategic the attorneys for the NAACP were when it came to selecting their particular plaintiffs.

And Oliver Brown, the lead plaintiffs in Brown the father of Linda Brown, who was the young girl that was denied entry into a white school. He was a minister, but he was also a member of a welder union. And what made him ideal is that because he was part of a union, you couldn’t really threaten to fire him.

and because he was going into the ministry also, he couldn’t threaten to [00:28:00] fire him. And so he was kind of, not to say he didn’t get threatened, but at least that couldn’t be taken away. Whereas some of the other plaintiffs in the other case were often harassed and told that they would, and some did lose their jobs as a result of being a part of.

Brown view board. And so what Brown View Board did ultimately is it looked at school desegregation and it talked about it, not just that it is, incorrect in its in it, but that, indeed Is, was unequal that how the student, how the schools came about, how the books were the teachers, nothing was equal about the schools is what the argument was.

But the second part of the argument that was really critical was the emotional toll that this takes on the children themselves. And that was made true by or made to be seen by the famous Clark doll test. Study. And so I think that that’s one of the things that they ended up happening is that so this, you know, very famous do test [00:29:00] eventually got the court Warren who wrote the majority opinion, eventually wrote and declared that separating the schools was inherently unequal.

And then the second part of that brown, two a year, later was they didn’t really give any guidance about how to integrate schools, how to stop segregation. And they end up just saying the phrase with all deliberate speed. And that is about as clear as mud. When it comes to being able to figure out what to do about this, what we now know, centuries long practice.

segregated schooling.

GR: I like that phrase as clear as mud. I mean, that could be a great title for some great studies on the subject of race and education in the us. And I say that in part because most of us who’ve heard about Brown, we know this about plaintiffs, we know they’re African Americans in the South, but you’re bringing up.

A dynamic of American history that we hardly ever talk about. And in your title, bricks Before Brown, you’re talking about at least [00:30:00] 100 other families before Brown, who legally challenged schooling, segregated schooling in the state and federal courts. Would you discuss a couple of key early cases profiling Chinese American, Native American and Mexican American plaintiffs?

Marisela:

Yes, absolutely. One of the first kind of interesting cases came in 1885 in the tape versus Hurley. And this was a case out of San Francisco and California and of course before Plessy, And so there, there was a large Chinese population, Chinese immigrant population, and there were a lot of anti-Chinese laws that were happening in that particular time.

And so there was this family, the tapes It was tapes because it was changed from Chew Diep is his, was his name. And they changed Diep to Tape and that was Joseph Tape and his daughter Mary Tape. And so they lived in a fairly wealthy part of San Francisco. And so they were actually closer to a white school.

But when they took, this, again, sounds very much like the Brown case [00:31:00] when the father takes the daughter to go and enroll in the school, they were brutally robust and told that they could not come to the school because she was Chinese. And they said that very clearly because she was Chinese, she could not attend the school.

And so the father ended up suing the school. Again, I’m, I’m sort of oversimplifying it, but he ended up su suing the school and he actually won the case. They won the case because at the time in California law Schools were supposed to be open to all children regardless of race.

That’s the way that the law was written. However, the judge, in his opinion, kind of did a weak wink. But if you can get the legislation changed, the districts can do whatever they want when it comes to schooling, including creating separate schools. So they delayed, delayed, delayed mamie’s entrance into the school while they started to build up.

A Chinese school, right? And so they ended up opening up a Chinese school for six children, [00:32:00] six children, just to keep these children out of white schools. They get, they developed an entire Chinese school to be able to do that. And so this again really I believe sort of started to kind of lay the foundation and added to the foundation of what eventually became pressy.

Interestingly though they’re not quoted, they’re not cited in Plessy, which I always found really interesting that all these cases that were involving school desegregation the only one they, I think the only one they referred to was you know, Robert Rebos, the 1849 case.

GR: Interesting. Is there a similar case for Native American and Mexican American plaintiffs?

Marisela: Yes. Yes, for. Native American plaintiff. One of the really interesting one that also laid the groundwork for Plessy was McMillan the school committee of district number four. And this was out of North Carolina.

And so North Carolina at the time was what they called famously tri-Racial. So, uh, it was black, white, and Croatan. And so what was so fascinating about this case is that there was a Croatan [00:33:00] act that was passed, which excluded all Negros to the fourth generation quote.

That’s what they called it, from white and Indian schools, cuz they were white schools and they were Indian schools. And so they all the Black families were denied from going to either one. Now in Millon, the father said, no, we’re part crottin. So we’re actually, we’re not black, we’re Croatan. And they, even in this case, what makes it remarkable, they even exhibited his son to the jury to be able to, I guess, prove their indigenous sort of identity.

And this really, really shows and talks about this idea of. Kind of common sense racism, like I know it when I see it sort of thing. And this was something that actually happened a lot in court where children were exhibited, right? And so they of course, unfortunately lost the case, And so this happened as you said, in 1890 which also laid the groundwork.

Another really interesting one was Maro v Grande, but this was an after Plessy. This was [00:34:00] a 1917 case out of Mississippi. Now, The school had prohibited all children who were, quote unquote one fourth negro, And so, the grands, however, under Mississippi law were recognized as white since it was illegal to marry anyone that was one eighth or more Negro life.

So their marriage was actually recognized, but their children were not. If that makes any sense. It doesn’t make any sense. But because they had what was called a slight strain of red blood, and this gets into that of the idea of blood politics and race, right? Because they had a slight strain of red blood, they were considered mixed and therefore, could not go to the white school.

hope I made that clear.

GR: It’s no, you did. we just don’t hear enough about the stories of, in this case, Chinese Americans, native Americans, Mexican American, and their long role to try and [00:35:00] obtain quality education in a non-segregated basis. That’s, it’s fascinating. grew up in Los Angeles. I’m a California boy, and you’ve got three court cases from that state.

And you’ve already identified some of the racial dynamics and what it meant to be white or non-white. Cause that definition has evolved in California since it’s founding. What are some of the, I guess, civil rights touchstones in K-12 education from reconstruction amendments to Brown that maybe California played a role in or that you’ve seen in your research?

Marisela: California He is the one that had the most fascinating sort of history. There were seven cases total that came out of California, and this is really where a lot of the Chinese and native American cases came out of as well, out of California as well as the Mexican American cases.

Right? was kind of this division between California and the south. the cases has either happened in California or Mississippi or North Carolina or Texas. Right. And so California, which is really interesting because it’s always [00:36:00] kind of had this role of sort of particularly the ninth circuit of being able to pave the way for real change that happens.

And I think that, when you look at the stories of Tate, this case I already told you about Piper, which is a Native American case in 1924 and Mendez. The case in 1947, a Mexican American case in 1947, is really, really fascinating to see the development of the deconstruction of separate but equal in California and how that eventually influenced right.

Brownie board. Now Mendez probably is the best connection. It’s actually my favorite connection to talk about. This is a 19 47 case involving Mexican American families. There were five families involved and over 5,000, I believe the numbers escaping the plaintiffs involved in the case. And so what had happened was because Mexican Americans at the time were considered racially white, legally [00:37:00] white, they could not bring a case under racial discrimination, right?

Because white people can’t discriminate against white people, So the attorney in that case called for, he explained that there was discrimination based on dissent, They’re dissent as Mexicans. And so that’s how he was able to actually get the case seen. before the courts, and then eventually as it started, bega becoming appealed right up to eventually the Ninth Circuit.

Now, what had happened with Mendez, a lot of people believe that Brown was the first one to use social science to be able to make its case when the truth is really, it happened in Mendez. In Mendez, they looked at two experts, an education expert and an anthropologist. To talk about the effects of segregation on the children themselves.

And so, Robert Carter from NAACP met with the attorneys from Mendez and basically said, you know, We wanna use this skeleton, That you’ve developed to be able to [00:38:00] apply it to our case, And so you begin to see some, a lot of similarities between Mendez and Brown. And I think the most critical connection is the fact that the governor of California at the time, one of the reasons why Mendez had not become a Supreme Court case, right?

Because it made it all the way to the Ninth Circuit and the schools didn’t appeal. To the Supreme Court because the governor at the time ended up integrating all the schools in California. So the governor was of course Earl Warren, who went on to become Chief Justice Earl Warren of the Supreme Court, and guessed what his first case was from versus board of education.

GR: Wow. I was unaware. That Mendez used social science information, data techniques before Brown. Interesting. I remember reading a note in a book about Thurgood Marshall where he [00:39:00] said the attorneys in the Mendez case are on to something. Pretty much yeah, too, they were onto something. And of course the rest is history.

And I was unaware. unaware that Warren’s first case was the Brown case. And there’s a very interesting political history as to why he was appointed to that position as related to even US presidential politics. So let’s bring this to a contemporary. Look right now, so many cities and the schools that they house there’s a lot of racial identifiability in terms of race and poverty in certain schools.

And you’ve had a chance to take a long look at this as you’re talking to your students at Morehouse College. As you’re talking to lawmakers, scholars, and others who are trying to think about how to use history and law to make sense of the challenges we have now. What are your thoughts about how this should form our thinking about equality of opportunity in schooling?

Marisela:

First of all, I, Love teaching about this. I love [00:40:00] teaching at Morehouse and I just have such brilliant students. I’m able to have the most meaty conversation, you know, with them. I always tell people that, I feel like I’ve had t mignon, instead of McDonald’s, teaching a class sometimes with my students.

And so one of the things that I explained to them that I talk about with my students is that when you look at there’s this idea, called there is nothing new under the sun. Right? Anything that you see today, you’re gonna be able to see happened in the past, In some historical way in, in definitely in a legal way, you’re able to be able to see the beginnings of something.

And one of the things that I explained to them is that in the foundation of education, Was already crooked, It was built crooked, starting from 1849 in Roberts v Boston when you had Sarah Roberts and her father, who was an abolitionist, Sue to go to the white school in Boston, right?

All the way to there to of course, brown, where you have Linda Brown, another little girl, and her activist [00:41:00] father Oliver Brown, end up sort of bookending. Again, I hate to use the same word, but. This gap that exists there now, it to be able to use law and history is that you’re able to see. And what I show them and, and what I hope I show in the book is you’re able to see the development of how it happened.

It didn’t happen overnight. It happened sort of like a death by a thousand cuts, or in this case, death by a hundred cuts, right? There are some cases at once but most cases lost. And you’re able to see. One of the things I wanted my students to be able to notice and to look at is that, First that, you know, when you talk about school segregation, it’s not just rooted in the south, right?

Everybody considers it’s just a southern thing. The other thing is that it’s rooted in the 1950s, That it’s limited to the 1950s. And my book and my research shows that that’s not the case. Right? And the other thing is that it’s limited to the black and white binary, and that all the cases involved black plaintiffs and white [00:42:00] schools.

And again, that was not the case at all. There were 14 cases involving Native American, Mexican American, or Chinese Americans. And so what I explained to students is to be able to understand this is a long way of getting, getting to the answer. To be able to really understand what happens today, you need to be able to look at the past.

And this school, our education system was never built on a solid foundation. It was built on sinking sand. So to speak, and because of that, ever since its creation, it has not been correct in the opportunities it gives particularly to marginalized populations in the us.

Cara: This has just been fascinating for us and this, we appreciate your scholarship so much and I have to say I always learn a lot. From our guests. And boy have we learned a ton from you today. This is fantastic. Thank you so much for your time today, Dr. Mariella Martinez, and we appreciate you just giving us this wonderful [00:43:00] work and putting this lesson out into the world for our listeners.

Marisela: Thank you so much for having me. I’m so glad that I’m able to share their stories. I’m not telling their stories, their stories I’ve already been told. I’m just happy to be sharing them. And so thank you for allowing me to share them.

Cara: Absolutely. And we hope to have you back. Thanks so much and take care.

GR: So my tweet of the week is from Karen BTUs. It’s from May 3rd, and it’s about a 2020 ranch study of civics teachers. Just 43% thought it was essential for graduates to know about periods such as the Civil War. And the Cold War, less than two thirds thought it essential for grass to no [00:44:00] protection guarantees by the Bill of Rights.

Hmm. I wish the numbers were higher. My tweet of the week.

Cara: This is a pretty good tweet and relevant to our prior conversation. Okay, Gerard the band will be together again next week as far as I know. And we are gonna be speaking with Dr. Diana Schaub. She is a professor of political science at Loyola University in Maryland, and co-editor with Amy and Leon Kass of the book What So Proudly We Hail the American Soul in Story Speech and Song.

Be looking forward to it. And until then, clap and appreciation for all of those teachers in our lives and uh, even former teachers still out there doing the good work. Thank you so much, Gerard. Great to hear your voice and excited to be back together again next week.[00:45:00]