“The Last Candid Man”: B.U.’s Dr. John Silber

/0 Comments/in Education, Featured, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffGuest

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a transcript here:

[00:00:00] Hello listeners, this is Gerard Robinson coming to you again from beautiful Charlottesville, Virginia, and not only is it beautiful, it’s in the low seventies. I just looked outside the temperature and it is great and looked at my phone. So ,it’s always good to be able to work on my tan in February as we’re ending Black History Month. What do you have to say about that, Cara?

[00:00:52]

Cara: I say yes, we are ending Black History month, and that’s very important. I wat to preface my comments with that before I say to you, blah, blah, blah. Gerard’s working on his tan. we’ve waited all this time for snow here in the Boston, at least my family has because we love to ski. We went all the way up to Quebec to try and —

Gerard: Wow.

Cara: To try and fly. Wow. Snow.

[00:01:18] The snow was okay, we come home, there’s nothing. And today, I will have to say I love my kids’ school, but they canceled school today for what panned out to be about an inch and a half of snow, so blah, blah, blah. I have no chance, but I mean, I wouldn’t anyway, but you know that, you know that, so, but it’s very good to hear your voice. It’s been a little bit since we have been together. Nice talking to you. If you don’t mind, Gerard, I would like to dive into my story the week, because I’ve got one that just really hit home today. I don’t know.

Gerard: Sounds good to me.

Cara: Start with a little story about my, my darling father who lives in Elk Rapids, Michigan, and Gerard, I don’t know if you know this about me, but as an undergraduate, I was an English major. I majored in English literature at Indiana University at Bloomington. And it was such a wonderful experience. I was originally a journalism major and when I went home to tell my father, who had unfortunately was suffering a health event, and I went to visit him and I told him at the time, you know, dad, I’m gonna change my major to English. And the man looked at me, Gerard, and he said “You need to leave right now because I might have a heart attack.” I’m so what do you mean? He said, do not tell me you’re gonna be an English major. And he wanted me, of course, to say that I was going to be a doctor or a lawyer. The things that we often hear from parents, especially those who might not have gone to college themselves—my father did, but he, he grew up in a really working class family, and not many people had gone to college, so he viewed certain careers as ones that would, support me well in the future. And that links to this very long, but really worth-the-read article in the New Yorker by Nathan Heller. It’s called The End of the English Major. So I’m going to try and be succinct. I’m not going to give you the whole article here, Gerard, but I highly recommend folks read it.

[00:03:10] I was so shocked. Did you know—just here’s just a couple of. Between 2012 and 2020 enrollments in the humanities fell 46% at Ohio State University, by 52% at Tufts University, and by 42% at Boston University. And this is reflective of a nationwide trend. That is a really short period of time for enrollments in the humanity and things like English and art languages to have dropped.

[00:03:46] And I think this feels really relevant to The Learning Curve because we have so many guests on this show that bring to us just wonderful insights and they’ve spent their lives in the humanities. It also struck me because I was having this conversation with my daughter the other day, who is only 13, but was talking about college and what she thought she might want to do, and my husband, who as you know, grew up in Argentina, where you don’t really have the opportunity for the kind of American undergraduate education that we know, where many of us feel that we might get four years to just study a bunch of things and find our paths. No, my, my husband went to medical school at 18 years old, basically. And we were saying to my daughter that she should choose something like follow her heart to study something that that inspires her. We weren’t having this conversation around go out and make money, which feels like a luxury, right?

But when I read these statistics, I was just shocked because it said to me two things. It said, number one, wow, people really don’t perceive these careers or degrees, I should say, as useful anymore. And two, what kind of emphasis is our society putting on the humanities and whether or not we’re going to lose this kind of education for folks.

[00:04:55] And so the article does go into some detail and, it, it locates a couple things. The first won’t surprise you. College is expensive, Gerard. I don’t know if you’ve heard university education is very expensive. People are graduating with a great deal of death and well, when you major in the humanities, you’re probably not going to make doctor, lawyer salaries. So kids, parents, families are seeing that and saying, don’t follow your heart. Pay off your debt. Make sure that you can support yourself when you graduate from school. And then there was some other really interesting insights here about the idea that we are in sort of this quantitative society.

If you think about the careers that we’ve been pushing, if we can look at the increase in STEM careers for the past couple years, something you and I have talked about before on this show, it’s pretty substantial. And what are the careers that we talk about in STEM? We’re talking about data analysis and data science, and we’re talking about engineering and technology sort of quantifiable things, and as one person in this article put it, we are living in a quant-minded society, meaning we think of a lot of things in terms of inputs and outputs and return on investment, and that a career in the humanities doesn’t just get you there now. Now, my bias is that we should really be asking a question, Gerard. What do we lose when we have so few students studying the humanities?

I don’t know that most of our high schools do a good job, public, private, charter or otherwise. And if we have fewer and fewer people interested in these subjects, which by the way have not been funded by the federal government in the same way that they have in the past, the national Endowment for the Humanities, these are, these funding has gone down.

[00:06:32] What are the consequences going to be for our society? I mean, I feel very biased about this as an English major who just loved her time and feels like it gave so much to my life. Of course, I went on to get a doctorate in education and not in English. So I don’t know, Gerard, all to say is you think about your family, your kids’ university, what does this say to you? This decline, this huge decline in humanities enrollment.

[00:06:55]

Gerard: Yeah, it’s been a decline for a number of years, partly driven [00:07:00] by the language coming from governors, including my former governor Bob McDonald who would say, do you really need anyone else majoring in philosophy? And I have to remind him that your secretary of education has a degree in philosophy.

[00:07:13] And so we’d laugh about it, but there are still other governments who are saying, we need workforce development and therefore we don’t need humanities. Well, I, you can use one example from our own show. So recently we had Gucharan Cas, who’s a former CEO of Proctor Gamble, India. You know what his undergrad degree is in philosophy from Harvard.

[00:07:31] He took that later, went on to get an MBA, but he used it to not only become a corporate executive, but he also became an author where he wrote about Indian philosophy, where he wrote about Indian literature, metaphysics. And so that’s just one. You are also correct. We’ve had guests on this show from Angel Parham who is a professor here at UVA to a number of who used their training and the humanities to either become a professor or to work in industry to work for nonprofit organizations.

[00:08:01] So think we’re missing something. I will say since you are in Boston, that all we should do is, you know, look at MIT, one of the top universities in the world. They decided several years ago that it was important not only to focus on STEM, of course, which they’re known for, but to also have required courses in humanities for STEM students, some of whom decided to double major or to have a concentration in humanity.

[00:08:25] So, I am not excited about that because I think we are going to miss giving students an opportunity to open their eyes, their brains, their souls to a different way of looking at life. But hey, this is why we have a Learning Curve. Someone’s going to hear this, possibly a lawmaker, possibly a governor, possibly a philanthropist who will say, “Hey, we need to donate money to focus on getting more students excited about the humanities.

Cara: Time to invest.

Gerard: And I knew you were an English major. Time to invest, right?

[00:08:55]

Cara: Time to invest. Yeah. What are you thinking about this week?

Gerard: Well, I’m thinking about two things. One is that as we go out of Black History Month and go into March, March is known for a number of things. But one thing in the K-12 law and policy arena, March is known for, is that 50 years ago, it’ll be in 1973 in March, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that in the San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, that there is no fundamental right to education. And we’ve had Professor Kimberly Robinson on the show, who talked about that case. And it’s going to be a really big topic for the next month and a half because people are just doing the 50-year review.

[00:09:34] So what does that mean for us? Well, I knew a lot about the case. I had a chance to participate a couple of weeks ago in a panel discussion by the University of Virginia School of Law Review, actually. And I just want to give a shoutout to them, because at a time when we are trying to censor speakers, or to only give one side of the debate, at this conference they actually had two former guests from our show on the panel who focused on the contemporary legal issues of school choice. They had Michael Benes senior attorney at the Institute of Justice who was on the panel with general counsel for the NEA. And when there was a conversation about education federalism, they had Neil McCluskey, director of the Center for Educational Freedom at Cato, and a professor from Georgetown.

[00:10:19] So, a shoutout to the organizers at that conference because they really brought in top-notch, well grounded, smart people who support school choice to have a conversation with their peers equally smart and grounded in their view. And so that’s great. Well, the panel ended by having closing remarks from Patricia Rodriguez, who’s actually the daughter of the Rodriguez case.

[00:10:38] And so I said, wow, this was fantastic to hear. Well, lo and behold, in doing some research, I also found out that San Antonio has another distinction that San Antonio, in fact, is one of the first Southern schools to move forward with a desegregating its system along before many other students or school systems did.

[00:10:57] And so, this is from My San Antonio. The title of the news article is “San Antonio ISD was on the forefront of desegregation in the South.” And so, I was unaware that even before the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that there was a then-named San Antonio Tech High School in San Antonio that had African American students in there before 1954.

[00:11:21] Now, once the integration process began to move forward in 1955-1956, there was a push by both blacks, whites, lawmakers, judges, and others to push the idea that we need to make sure we integrate our schools. Well, by the time we get to 1964, even though you had challenges in places like Houston, Texas you had a push toward desegregation in San Antonio that you didn’t see, not only in other big cities or school systems in Texas, but also around the country. And so, whenever I hear something like this, I said, was there something in the water, or was there something going back to post-Reconstruction or maybe right after the Civil War that led—or at least planted the seeds for this—well, it was a little bit of all of it.

[00:12:04] And so what the author identified was that after the Civil War that the Freedman’s Bureau out of DC set up a number of schools throughout the South that played a role in helping to establish a system of education in Texas, but also in San Antonio, but by 1871, Texas had organized an official public school system, but that led for a push to get more blacks into schools in that city. And so, there is the Recon School for African Americans, which opened in 1871 at about a hundred to 170 students. Well, fast forward to 1888, and you will definitely understand that this is an Irish Catholic woman.

[00:12:42] Listen to the name! In 1888, Margaret Mary Healy Murphy opened the St. Peters Claver Colored Mission, which was the city’s first Catholic school for black students, and then philanthropists and others went forward. So, it’s a story that as we talk about what happened in San Antonio 50 years ago with school—what decision that case had on school funding today, San Antonio should also at least take one cheer for saying, yeah, I hear you, but when other school systems in the South and in Texas ini particular, didn’t want to desegregate, we were moving forward with the work. What are your thoughts?

[00:13:20] Cara: I think my thoughts, Gerard, is that I have never been to San Antonio, but I want to go because I am not surprised by any of this because I think San Antonio, somebody out there will correct me if I’m wrong, but I think they were the one of the first school districts to really meaningfully think about how you weight funds. And this is recently so that students who have at least access get the most, and they’re doing it more in a, a system that involve controlled choice for families, that they’re doing it in a way that really allows students to find a school that fits them well. And they’re also on the forefront of funding pre-kindergarten in a way that many districts have failed to do.

If I recall, this was something that a great 74 reporter did sort of an expose on a few years back, but yeah, I mean, it’s —thank you for that because we do always think about the federal decision, San Antonio versus Rodriguez, and the impacts that that had and how it sort of spurred all of these other cases.

[00:14:16] But San Antonio, I am not surprised that San Antonio is so important in this history. And I also love—I wish that we could go beyond Black History Month to dig up these really wonderful nuggets and stories of black history about people that are doing good and on the cutting edge. And I’ve got to say, I mean, of course you’ve got a good Catholic school in there at some point.

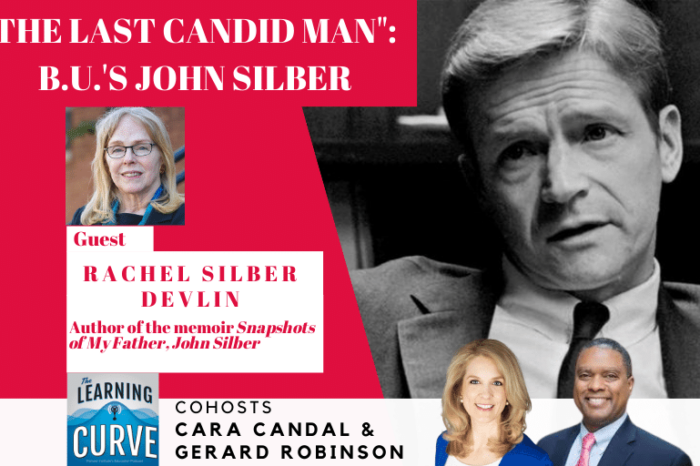

[00:14:38] That’s sort of how these things go. This story brings everything together, Gerard. So, thank you very much for that. You know, we’ve got a really interesting guest waiting for us, somebody who is sort of close to my own history. We’re going to be speaking to the daughter of the late Boston University President John Silber. We’re going to be speaking to Rachel Silber Devlin. And of course, she’s not just John Silber’s daughter, but she also is the author of a new memoir called Snapshots of My Father, John Silber, and that’s in addition to some of her other wonderful work. So, we are going to be speaking with Rachel Silber Devlin right after this.

[00:15:34]

Learning Curve listeners, as promised, please help us welcome to the show, Rachel Silber Devlin. She is one of John Silber’s six daughters, as well as a wife, mother, homemaker, and author of the memoir, Snapshots of My Father, John Silber. She divides her time between Texas and Massachusetts, both states we were just talking about at the front of the show. And those are the states where her children and grandchildren live. Rachel Silber Devlin, welcome to The Learning Curve.

Rachel Silber Devlin: Thanks very much. It’s good to be here.

Cara: Yeah, so, as I told you before we started recording, I had the privilege of meeting your father for a book that I edited many years ago, and he’s just a great figure, especially in the history of Massachusetts, especially Boston University. And I think that as a doctoral graduate of the Boston University School of Education, I certainly felt the mark that he left, he really, I think, in a lot of way raised standards for that particular part of the university for across the university, but particularly for the School of Education. So, we’re excited to learn a little bit more about him. Could you share with our listeners, like a brief overview from your memoir about his family, your family, and his upbringing in Texas?

Rachel: He was brought up during the Great Depression in Texas and his father was an architect and for that time he had a hard time finding work. And his mother went back to teaching. She had taught in a one-room schoolhouse and she went back to teaching in San Antonio during that time. But when he met my mother, he was so impressed with how well they lived considering that it was during the Depression. And they traveled a great deal, and they did that by taking along bedrolls and sleeping bags and food that they cooked so that they wouldn’t always have to stay in hotels and go to restaurants.

They could camp out, and my dad just thought that was so smart that they didn’t worry about looking like hicks or something. because they were happily seeing the world or seeing at least Texas. So, when my sisters and my brother and I were young, that’s how we traveled. My dad used that as a model and we would always take air mattresses with us and we would camp out in one or two hotel rooms even when we got to be seven children.

[00:18:04] And that way we went all across the United States many times and traveled around Europe at least twice. So, we enlarged our horizons. But Pop always did believe in making life just a little more difficult for your children than your means might allow. He thought it was—he thought it was a good way to get you ready for life’s adversity.

[00:18:24] Cara: That’s actually, I have to say in, what I know of your father and the mark that he left on higher education and the way he thought about managing such a huge university, I am not surprised by that story. Now, you’ve described a little bit about how you grew up, but during the sixties, he was the dean of the college of Arts and sciences at the University of Texas, Austin. And this was one of the first places where he, he really made his name. So, I think it’s safe to say, not only was your dad known as a huge proponent of a traditional liberal arts education, something we were also talking about at the beginning of the show, but he was a very vocal civil rights advocate and an opponent of capital punishment. He had quite a reputation. He was, you know, I think many would say a controversial leader in higher education, though. Certainly dynamic. Talk a little bit about that, how his career was shaped and how this reputation of his sort of propelled him.

Rachel: My dad was always such a bold character. He was always just very alive and in the moment. When he was in college, he had a job during the summers as a census worker, and he found some areas where people were living under such inhumane conditions that that really was an eyeopener for him. When he became a teacher at the University of Texas, he taught hundreds and hundreds of students in what was called [00:20:00] Plan Two there. It was a kind of a great books, great philosophy class. And his one big assignment each year for all of the students was to do something he called the Slum Project, and he would send all of the students.

[00:20:16] out to find an area of urban blight and to investigate that property and find out who the landlord was and if the landlord was fulfilling his obligations to the people who lived there. And this was serious work for these young undergraduates. But it was his idea of activism as an activity that was positive and within the law.

[00:20:43] And it was never just shouting down the other side. Also as a young professor, he wrote an article on how to break the cycle of poverty with early nutrition programs and early education. And that article was so well received that that’s when he was asked to be on the commission that created Head Start.

And that was really the beginning of his lifelong interest in education. And of course when he came to Boston University a first-rate education was what he was trying to bring to every student as well as a cultural environment that would be a wonderful place for them to learn.

Cara: I’d like to pick up on his time at BU for a minute, because you’re saying two things, like he really wanted to raise the standards and he reached out to the community. So, I mean, just, a couple of notes here. So, for example, even when I was at BU, he had Nobel Prize winners. He attracted Nobel Prize winners to the faculty, Elie Wiesel, Sheldon Glasgow, Derek Walcott, these are incredibly heavy hitters. He raised the endowment, which allowed us to increase research grants. He really—he built out Kenmore Square. \My father grew up in the Boston area, left and moved to Detroit when I was at [00:22:00] BU, he came back and couldn’t believe what that university had been transformed into. Much of that to your father. And at the same time, his impact on the community. The book I co-edited was about our Boston University’s involvement in turning around the Chelsea Public Schools, for example.

[00:22:17] And that was your father essentially going to the Massachusetts legislature and saying, we can do this. And, I think by many measures he did. So talk a little bit more about how he grew up in his vision of what a modern university should look like. Really helped shape the BU that people like me experienced.

[00:22:35] I bet your father was surprised, but there’s no more Lucifer’s in Kenmore Square, the old nightclub that used to be there.

Cara: Yes, he was!

Rachel: But yes, he did bring first rate teaching to Boston University and he attracted Nobel to prize winners. So, half of those that you listed were not Nobel Prize winners when they came to BU. They only were honored [00:23:00] after they’d been at BU for about 10 years. So it’s partly a cooperation with Boston University. But he was always interested in these teachers who would be interested in not just continuing their research and writing their books. They had to also really be interested in teaching students.

[00:23:22] That’s what he was looking for, the experience for the students. And under his guidance, the core curriculum was created at Boston University. Taught great books, great ideas of literature, philosophy, and science, and was a wonderful program that was a great addition to the campus. Also, ,just the fact that he always championed freedom of speech which is the only way learning can be.

[00:23:50] When students don’t feel that they can express opinions or follow opinions where they lead the conversation cannot happen and the mind [00:24:00] can’t grow. So in order for education to really happen, freedom of speech is essential. and he also made sure that protestors were not allowed to shout down the other side or close down events where conversation and debate was taking place. He really never did that in an authoritarian way. He was doing it to protect the rights of the students and faculty and staff who were involved in these events where an exchange of ideas could take place.

[00:24:36]

Gerard: If I can stick with his work at higher ed. Cara mentioned that he was involved with the Boston University, Chelsea, a partnership some graduate work. At the time that I was studying, I was looking at, partnerships and school takeovers. He did this in part as a president. You mentioned Head Start. In 1996, he was appointed chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Education.

[00:24:58] Many presidents want to focus solely on higher ed, and I truly understand why. But he saw higher ed and its link to elementary and secondary education as being vital to his work. Talk to us more about his vision and why he decided to take this approach.

[00:25:15]

Rachel: Well, freedom of speech in higher education is not enough. Students also need an adequate school system so that they can even reach college so that they have a chance to go to college. My father deplored the school systems that seemed to just move the students along through the grades and then out the door without ever delivering the education that they had promised.

And that’s one reason he was in favor of testing, testing students along the way and testing them at graduation. He never really saw that as just testing the students. He saw it as testing the teachers and testing the school system to see if they were doing their job so that they could see where they were not succeeding and where they could have some improvement.

[00:26:12] He also quite often found the Department of Education guilty of protecting poor teachers, and he thought it would be better if teachers didn’t all have to go to a school of education to get their teaching credentials. He would like to have seen teachers who had a degree in some particular subject, but who wanted to be teachers—find a way for them to join the teaching faculty of a high school without too much more rigorous education so that they could actually make a contribution. He also started the greatest scholarship program in public education across the country that was called the Boston Scholars Program.

[00:26:57] That gave 100 students, top students in the Boston Public Schools scholarships, to go to Boston University each year. And then later, Mayor Menino started working with him on it and they became good friends and they worked on it for years.

[00:27:13]

Gerard: Your father was also an author celebrated novelist. Tom Wolfe referred to your father as the Last Candid Man, and he authored two books—well, two that I’ll reference. Architecture of the Absurd: How “Genius” Disfigured a Practical Art and Kant’s Ethics: The Good, Freedom, and the Will. Would you talk about his retirement years and how these two helped to encapsulate a robust, highly successful life and public career.

[00:27:40] Rachel: When Pop wrote Architecture of the Absurd, it was shortly after, first my brother died of AIDS, which was a terrible tragedy in our family. And then my mother died, and it was such a surprise to him that a project could bring him such joy. So, it was a great thing to have written this book that is a real gem on the subject of modern architecture. He found it so easy to write with his wealth of knowledge that he had gained from being the assistant to his architect father on many of his projects, and being so interested in architecture all his life.

Then that helped charge his battery so that he was ready to attack his real life’s masterwork. He felt his book on Kant’s ethics. He had been working on it since 1960 and he had lost some material when an arsonist burned down the president’s house shortly after we moved to Boston. That was during some times of great protests on college campuses. But he completed that work. It was, an iming for him to do. And then he worked on compiling his best speeches into one book called Seeking the North Star. And to me it’s just such a wonderful thing to have his great life of the mind so encapsulated in one book that I can look into on occasion and see his well-formulated, beautiful thoughts and bold thoughts, always bold.

[00:29:27]

Gerard: You actually made me think of just one thing, and this is will just be a parting question. In 2023, we have a number of openings for college presidents both in the public and the private sector. Knowing what you know about your father, of course, your own wisdom that you bring to the conversation, what kind of advice would you give to an incoming president of a top American university today?

[00:29:50]

Rachel: Well, I still think that the most important issue is freedom of speech, and I think for you to have that, you cannot have anything called a safe space on a college campus. My dad would think the whole university is a safe space. It’s a safe space where you can express any thought in a safe situation where you should be able to express anything and have a conversation with people who have opposing views. You should not be protected from hearing views that you don’t agree with. So, I do think that that would be the most important issue.

[00:30:33] Gerard: Thank you. Well, we want to just give an opportunity to read a passage from your book, and then once you do, Cara will close us out.

[00:30:42] Rachel: This is an excerpt from Snapshots of My father, John Silber, from the chapter called Still Grounded.

“Once when a news story asserted that my dad was intimidating, Pop explained to Colin [Riley, the director of media relations at Boston University] that no one can intimidate another person unless that person agrees to be intimidated. In his view, it had more to do with the thin skin of the one who feels victimized than with anything done by the supposed perpetrator. I must say I see a great deal of truth in that.

Another time, Colin was tracking down all of Pop’s essays in their original form… The one essay on the list that was most elusive was a high school paper. It was titled “Truth or Tact” Colin never found that paper, but he was fairly certain what side John Silber came down on. Part of the regular routine was that the office staff sent pop’s schedule to mother at the Carlton Street House, and this was updated over the phone sometimes when Pop called the house. He liked to put on a thick foreign accent to trick Catherine. He especially liked to pretend to be Henry Kissinger [00:32:00] asking to speak to John Silber. He had practiced imitating Kissinger’s voice ever since his time serving on the Kissinger Commission regarding Central America. Mother could usually tell, but that didn’t stop him from trying.

[00:32:15] One time, Martha’s new piano teacher telephoned and introduced himself to Catherine in a thick, hard to understand accent, and she said to him, oh, John, I know that’s you.’”

And I’d like to just—I’d like to just close with a quote from my father on what it means to be a true liberal. “One is not a liberal, but an idealogue if one joins the thought police to enforce political correctness in society, and especially in academe. The idealogue of the left is no more liberal than the idealogue of the right for neither believes in humility before the facts and logic, respect for the experience and views [00:33:00] of others, and the importance of making a supreme effort to avoid irrationality.”

[00:33:06] Cara: Rachel Silber Devlin, I can only venture to guess what your father would have to say were he with us today to comment on some of what he’s seeing, not only on college campuses, but just across the country on both sides of the political ideological spectrum.

[00:33:22] Rachel:” I’d love to be able to ask him.

[00:33:25] Cara: I am sure you would. And what a lovely little nugget to end on with a story about your father trying to trick your mother on the phone. Yes. Something that I think those of us who knew him only as, you know, this leader of a university would be very surprised by. So, thank you for that, great. It was wonderful to have you with us. Thank you for your work. Thank you for your time. This was a lovely conversation.

Rachel: Oh, it was a great pleasure. Thanks so much.

Cara: We’re gonna close it out with our Tweet of the Week and ooh, this is a spicy one, Gerard. This is from Education Week, tweeted on February 24. The nation’s second largest school district is investigating a cyberattack that comprised the personal information of an undisclosed number of contractors. I mean, ouch, And this is LA USD. Certainly, probably no fault of their own. This is cyberattacks everywhere. It made me think of a story that just broke on our own local news stations today that a crypto mining operation was found in the basement of a high school here in suburban Massachusetts. How did they find out? They found out because it takes so much electricity to mine crypto, that this person had set up an operation in the school basement to save some money while he was doing it. So, we’re in a new world, Gerard, where school districts hold a lot of data, a lot of information about folks, are on the defense just like the rest of us that, you know, live in the world are when it comes to keeping things private, keeping personal information at bay, and, making sure that the things that are supposed to go on in our schools are going on in our schools and not other things.

[00:35:49] Gerard, we are going to be back together again soon because next week we’re going to a be speaking with Lauren Redniss and [00:36:00] she is the author of many works, including Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout. So right back to my point at the beginning of the show, this has to be a humanities person, and I’m sure it’ll be very enjoyable.

[00:36:13] Until then, Gerard, take care of yourself. Work on that tan. I’ll be up here freezing my butt off.

[00:36:21] Gerard: And hopefully more snow will fall.

[00:36:23] Cara: Well, listen, if we can ski, it’ll be worth it. Gimme the good snow. No, not this stuff. You take care of yourself. We’ll talk next week.

[00:36:30] Gerard: Take care, my friend.