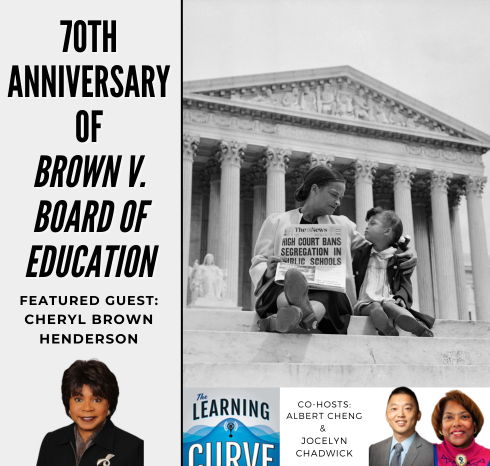

Cheryl Brown Henderson on the 70th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

TheLearningCurve_CherylBrownHenderson

[00:00:25] Albert Cheng: Hello, everybody. Welcome to another episode of the Learning Curve podcast. I’m one of your hosts this week, Albert Cheng from the University of Arkansas. And hosting with me, co-hosting with me this week is Jocelyn Chadwick. Jocelyn, good to see you again.

[00:00:41] Jocelyn Chadwick: It’s good to see you too, albert. I’m glad to be here today.

[00:00:44] Albert Cheng: Yeah. I still think about your reading of Langston Hughes last time you were on.

[00:00:47] Jocelyn Chadwick: Ah, yes. That was very interesting. And I’m really glad that we were able to do that.

[00:00:54] Albert Cheng: Yeah. we’ve got a great program this week. First, I want to give a shout out. It is National Charter Schools Week. If you’re paying attention to that or didn’t know, check that out. National Charter Schools Week has started. It’s this week. But also, this Friday is the 70th anniversary. of key Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education. To commemorate that, we’re going to have Cheryl Brown Henderson on, and I’ll introduce her later, but she’s one of the daughters of the late Reverend Oliver Brown, who is the plaintiff in this case. really excited to get into this week’s show. Jocelyn, before we do all that, though, let’s do some news. Do you have a story that you’d like to share?

[00:01:31] Jocelyn Chadwick: Oh, yes. I have one I would love to share. It’s Opinion, How to Help Third Graders Struggling to Read, Don’t Socially Promote Them by Mitch Daniels. And I must say, as I read this op ed piece, I have never seen, nor read, nor heard the word of the author Educrat.

[00:01:53] And I thought, that’s a first for me. And I went to the Oxford English Dictionary, and the Oxford English Dictionary says that it is a word that is only used here in the United States. And it denotes a tyrant who happens to be a teacher. And I really took umbrage with that. So I did the op ed piece.

[00:02:12] Objectively, because I do that, that’s just what I’m supposed to do. And while I understand the position about social promotion, it seems to me that in this one, in this particular article, the writer decides, Mr. Daniels decides that he’s going to paint all educators and administrators, as he calls them, with a broad brush of educrats, establishment of unions and career administrations.

[00:02:39] I would like to say just, against it first, that not all teachers are members of unions, not all unions are bad, and not all administrators are career administrators who don’t care, which is what he says. That is his primary thesis here, aside from We should not socially promote students who cannot read.

[00:03:01] The focus of it is on reading, but Mr. Daniels doesn’t seem to want to focus on that. But I want to focus on his point about it. Third grade, if a student hasn’t learned to read by third grade, we’re really in trouble. So where does it begin and who’s responsible? And so, my response to this Op ed piece is, number one, reading begins in utero.

[00:03:25] If parents read to their children and let them listen to music and all of that, it does have an impact, as well as parents playing a key role in having reading at home. Out loud, storytelling, reading books, papers, everything, reading in the grocery stores, reading billboards. It’s just reading, and parents are with them 24 7.

[00:03:49] Teachers are to teach. We teach reading, especially English language arts, but in all of our classes, in all core content areas, there’s reading. And administrators, I know some amazing administrators who work with their teachers and who, even when I’m teaching those classes around the country from fourth grade through 12, and I’m guest teaching.

[00:04:08] Lecturing with them or teaching. Sometimes the administrators are in those classes, and they become learners and exemplars for their students. And the other, of course, is the community and the community libraries and so forth. All of those things combine to help students learn how to read. This idea of calling all teachers and administrators educrats, I think, is specious. And I would love to have a conversation with Mr. Daniels one of these days.

[00:04:38] Albert Cheng: Yeah, and just to even speak a little bit more on this, the issue. here in Arkansas, we’re making a pretty great, big effort to ensure reading readiness by third grade. And there’s some policy levers that are being pulled, teacher training and some work on curriculum and pedagogy. But, I got to agree with you too, as well, that it takes a lot of folks, both inside the school, outside the school, to get our kids to read. Hopefully I’ll have some really good news to share come out of Arkansas in a few years, once these new programs and policies get implemented and running.

[00:05:07] And I know a lot of states across the U. S. are also engaging in some of these efforts. So yeah, hopefully we can make some progress here. It’s an important issue.

[00:05:15] Jocelyn Chadwick: Absolutely. Yeah.

[00:05:17] Albert Cheng: Speaking of remediation, Jocelyn, I found a news article this week about something that Newark Public Schools in New Jersey is doing.

[00:05:25] They’re going to use Khanmigo. I don’t know if you’ve Played with this is Khan Academy’s AI tutor. And so again, speaking of remediation, this is, its old news, but important news where, we’ve had a lot of loss of learning progress since the pandemic. And so, lots of school districts are trying to figure out some interventions and ways to catch kids up and address learning gaps.

[00:05:48] And so Newark Public Schools is going to start using Khanmigo to help tutor their students. You know what’s it is, what excites me about this? I. I’m, I wouldn’t say I’m bullish about AI, I don’t know what to think, if you ask me to predict if it’s going to be wildly successful or not, I’m moderate, but, what I appreciate about this news article is that, and what Newark’s doing is that they mentioned a call for more research, and they’re actually going to do an evaluation of this program. And so, we’re going to be able to learn with some data and evidence about the effectiveness of this initiative. And, hopefully this research will have something to teach, not just Newark Public Schools, but all districts across the country, all schools, public, private as well. So hopefully it works, but we’ll see.

[00:06:32] Jocelyn Chadwick: I totally agree with that. I, again, like the idea of AI. This is the 21st century and Gen Z. there is, it’s not either or. I know that folks think that you cannot read a book unless you’re actually reading the book. My iPad goes with me everywhere, and I’m reading and notating books. And I get the idea that. I like what they’re trying to do. The idea of just investigating and exploring and trying to address our students where they are and bring those of us who are teachers from a long time ago into the future.

[00:07:02] Albert Cheng: Yeah. If there’s one thing that’s going, there’s plenty of research out there suggesting that tutoring is a pretty good intervention for catching kids up. We’ll see how it goes when we do it. Shift from a human-to-human tutoring arrangement to an AI to student. So anyway, let’s stay tuned to see what happens there. Stick with us because coming up after the break, we’re going to have Cheryl Brown Henderson, who’s going to talk to us about Brown v. Board of Education and her own experience with it. Stay tuned.

[00:07:49] Cheryl Brown Henderson is one of the three daughters of the late Reverend Oliver L. Brown, who, with NAACP attorneys, filed suit against the local Board of Education. Their case was appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court on May 17, 1954, and became known as the landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

[00:08:12] Cheryl is the founding president of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research, and owner of Brown and Associates, an educational consulting firm. She has an extensive background in education, business, and civic leadership, having served on and chaired various local, state, and national boards. She earned a bachelor’s degree in elementary education, minor in mathematics from Baker University, Baldwin City, Kansas, a master’s degree in guidance and counseling from Emporia State University in Emporia, Kansas, and honorary doctorates from Washburn University and the University of South Florida. Cheryl, I want to welcome you to the show. It’s really great to have you here with us.

[00:08:53] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here. This is a very busy time with the anniversary of Brown v. Board coming up, one of the major anniversaries. I welcome the opportunity.

[00:09:02] Albert Cheng: Great. Yes, it is. As for our listeners who are tuning in, it is the 70th anniversary of that landmark ruling. So, Cheryl, let’s talk about the case and just some of the background in it. Particularly, a lot of the folks that are involved, many of them very well. So, can we start with your father? Would you share with our listeners more about Reverend Oliver Brown and just your family’s experiences growing up in Kansas in the 1950s?

[00:09:28] Cheryl Brown Henderson: That’s a tall order, because Brown v. Board is very complex and multifaceted, as people are coming to learn, and a lot of people, I believe the general public, may have a sense that it’s something that happened somewhat in isolation. However, it was a long campaign, and those of you in Massachusetts know full well that it was about 105 years in the making, between, the first case documented in Boston, Roberts versus the city of Boston, all the way to Brown v. Board in 1954, 105 years. And in that ensuing time, however, there were multiple school desegregation cases in my home state of Kansas. And as a native Kansan, I’m always thrilled to be able to educate people about the significance of the state. Kansas just happened to be an extremely consequential state.

[00:10:20] With respect to the civil rights in this country, the civil rights movement, what happened post-Civil War, all of that. And I think all of that fed into the fact that Kansas was a hotbed of activity around litigating school desegregation cases starting in the 1800s. So, from 1881 all the way to 1949, 11 school desegregation cases.

[00:10:44] In my home state, they were litigated in the state Supreme Court. So, Brown v. Board in Kansas was not an anomaly, was not unique, and it was not unexpected that there would be an additional attempt at integrating public schools. The sea change, however, was rather than state Supreme Court. Brown v. Board was taken to federal district court. And that’s what really opened the doors for what we are experiencing, what happened after Brown v. Board, was putting it in the lap of the federal government, the part of our country that had the interpretation of the Constitution as a responsibility. And that made all the difference in the world in moving this along.

[00:11:27] Albert Cheng: Let’s continue talking about the case a bit more. What was your father’s experience carrying out the Topeka NAACP strategy of having African American parents attempt to enroll their children in white only elementary schools?

[00:11:42] Cheryl Brown Henderson: My father was one of these people at the time he was studying for the ministry, and he was a very family oriented, a very loyal person in terms of friendships, and it just so happened that one of the attorneys for the NAACP, working on organizing this litigation, had been a boyhood friend of my dad’s.

[00:12:04] His name was Charles Scott, and ironically, both Charles Scott and his brother John Scott were attorneys for the NAACP along with Charles Bledsoe. So, Charles Scott called on friendship. He came to our home and asked my dad if he would be willing to join this litigation they were organizing. To desegregate elementary schools into people, because in our family, three girls, my mom was expecting me, so I guess I won’t say three girls, two girls and a baby on the way.

[00:12:33] And so Charles wanted to know if dad would do this. My oldest sister Linda was the oldest in our family and the only one in school at the time. Charles had claimed to my dad that they were recruiting all over the city, going to churches, talking to other friends and neighbors who were African American to solicit, getting them to sign on, because in the 1950s, perhaps not so much in Kansas, but around the country, particularly in the South, it was a risk, it was risky to take a public stand against Jim Crow laws, which is what, in essence, he was asking them to do.

[00:13:06] So my father contemplated and did not say yes immediately. There were nine people on the roster when they came to our home when Charles came, and nine of those were all women, married women, and homemakers, but women, nonetheless. So, one of my dad’s questions and reluctance was, are you planning to recruit other dads? Will there be other fathers involved as plaintiffs, and Charles assured him that they were still recruiting. Of course, he couldn’t deny that. Answer beyond that. it really took some convincing on the part of my mother, and I can be very persuasive, and explaining to my dad that as someone studying to become a pastor, someone that would soon be leading a congregation, someone who by virtue of that role would be seen as a community leader, that this was the right thing to do, not just for our family, but for the community and for his eventual congregation.

[00:14:00] Charles came back in a couple of weeks, and Dad agreed that he would join the roster. just that simply is how my father got involved in the first place. And then, once they met, in the fall of 1915, they ended up with 13 families that had agreed to sign on as litigants. They were instructed by the NAACP to locate a white school near your home, and take your child or children and a witness, and they did. And it came to enroll, because that was the evidentiary part of this. They needed that documentation of being refused the right to enroll their children. It was very technical. It wasn’t high drama, perhaps as it was in South Carolina or Virginia, places in the South. It was very matter of fact and very. My father and his fellow 12 plaintiffs spread out across the city attempting to enroll their children in white schools close to home. We lived in integrated neighborhoods.

[00:15:00] Cheryl Brown Henderson: These schools were in our neighborhoods. It was just that based on race, you were assigned to a school that was segregated for African American children and could not go to the neighborhood school unless it was a segregated African American school. And the one in our neighborhood was not.

[00:15:17] Albert Cheng: So, you’ve told us a bit about how your father got involved and how the lawsuit was actually filed. I’m curious to hear more about that if you have anything else to say, but I also want to hear about the 12 other families that were involved.

[00:15:29] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Yeah, I’m glad you asked that.

[00:15:32] His fellow plaintiffs, or those that signed on as well, and actually, as I said, many of them signed on before my dad. These were moms. These were married women, homemakers back then. The traditional families, I’ll put it that way, really wanted something better for their children. They wanted them not to have to walk blocks and then ride many more blocks to attend school when there were schools down the block.

[00:15:57] They would often talk to their white neighbors, the moms would talk, and the kids played together after school, played together all summer, and the moms would step outside often and talk about how This made no sense, that the only difference was when the school bell rang. My child goes one way, your child goes another way, then they come back together in the evening.

[00:16:18] It just makes no sense. Some of the women were from small towns and had moved to Topeka, the big city, the capital city, as young women, prior to being married. So, they had already lived in integrated settings and attended integrated schools. Because Kansas Only allowed segregated elementary schools in cities of 15,000 or larger.

[00:16:41] Mrs. Todd, for example, from Little Oak, Litchfield, Kansas, small town, gone to integrated schools, gone to Pittsburgh State University, integrated college. Mrs. Henderson from Oakley, Kansas, way out west near the Colorado border. Moved to Topeka and all of a sudden, her rights, as she says, I didn’t have as many rights as I came here with. So a lot of these women, I think because of their experiences in small towns, wouldn’t stand for, what they were witnessing in Topeka after having lived under different circumstances.

[00:17:13] Albert Cheng: So, I want to ask you a bit more about your father, just to shift back to him. You mentioned that when this all got started, he was about to start his role as a clergyman. And so this is, he’s similar to a lot of the other civil rights leaders that are familiar to us. Dr. Martin Luther King, Fred Shuttlesworth, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, all of them were clergymen. So could you discuss the central role that faith and religion played in your family’s decision to be plaintiffs on this case?

[00:17:40] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Yeah, I think that’s quite telling, the litany, the men’s names that you just read a minute ago, quite telling. The African American church is always the gathering place in, within our communities. It’s a safe space, to borrow from some of the current terminology, and a lot of the strategy and strategic sessions around protest marches, and obviously Brown v. Board as well, it took place in those hallowed halls. I always talk about the Black church or African American church as being the first social service agency. It was a place you could go if you needed help of any kind. It was a place you could go, if you needed counseling and support. It was always Looked at as not just a place of respect and spirituality, but a place of safety and security and guidance, and I think that’s why, when you look at the men you named, why the Church is front and center.

[00:18:35] Dr. King, as a young man, become, pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Berta Johns, before him had been pastor and very much an activist, and left in part because of that activism which led to the bombing. And ironically, Bertha Johns niece, Barbara Johns, was a young woman who organized the strike in Farmville, Virginia, that ended up being one of the cases in Brown v. Board of Education. So, a lot of this activism emanating from the Black church.

[00:19:04] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Where we were taught, for public speaking, we were taught leadership. We were taught there was responsibility to uplift our race, ourselves, to always represent in a positive way. I think it was reflective throughout the country when you look at the other movements.

[00:19:19] Albert Cheng: Let’s pivot a little bit and get into the nitty gritty of the case. Earlier in the previous question, you were mentioning how school segregation was an issue everywhere, just across the whole country, it wasn’t just a Kansas thing. And the term separate but equal. Dates all the way back to 1849, so this is, years and decades before Brown v. Board. In a court case, Roberts v. City of Boston, northeast city, that was a case that sought to end racial discrimination in Boston public schools. Could you catch listeners up to what was going on in other districts and other places like the northeast and the Midwest as the case was developing?

[00:19:54] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Yeah, after Plessy v. Fergus in 1896, which gave us that doctrine of separate but equal. It spread like wildfire, to be honest. We often talk about the Civil War, and my thinking on that is always that the South won the physical war, but they won the war of ideology. Because the ideology of keeping African Americans and whites separate, the ideology of the Civil Whose children do we invest in and second-class citizenship and everything that the Civil Wars seem to represent seem to be a sentiment shared in many other places. And so not only in the Northeast, when you talk about Roberts v. the City of Boston, but also as far away as California, Asian desegregation cases, Latino, Mendez versus Westminster. So, this was all about in my view. Built in, or baked in, disadvantage. creating disadvantage for certain populations.

[00:20:50] If we talk about a level playing field, we know full well, by looking at the record, the historic record, that it was very much intentional that certain groups of people would be disadvantaged in this country by not being Afforded equal educational opportunity, not being afforded, up to date textbooks and facilities that would accommodate children without leaky roofs and broken windows.

[00:21:13] And we can’t pretend that all of what we’ve seen and all of it we’re talking about now that was not just in the South was not intentional. It was very intentional. And the post reconstruction amendments, 13th, 14th, and 15th, that sought to make a difference after the civil war. We all know Reconstruction was short lived.

[00:21:35] Jim Crow and Black Codes and that sentiment, became the law of the land, even though it wasn’t law in the true sense. But other parts of the country were no different. And even though Kansas had been a free state, not a slave state, even though Kansas offered certain we’ve had levels of integration in neighborhoods and some workplaces, but still there was that issue of education. That’s where we fell in line with the southern sentiment of racial segregation.

[00:22:06] Jocelyn Chadwick: Cheryl, this is Jocelyn, and I just first want to thank you. Hello! I first want to thank you. Your parents certainly blazed the trail for people such as myself coming after, after Brown v. Board. So, thank you. And listening to you talk about your parents, just, I’m just sitting here smiling and I’m really happy about that.

[00:22:25] So let’s continue. Last week on our podcast, we hosted the biographer of Justice John Marshall Harlan, author of the famous dissenting opinion in the notorious 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson. Will you talk with us? about why people should know about and remember the Plessy decision and Jim Crow segregation.

[00:22:50] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Obviously, Plessy v. Ferguson is what set all of this into motion. And Plessy v. Ferguson is what made a Brown v. Board necessary. And as we know, beyond Brown, it made the civil rights movement necessary. It made the legislation that came after necessary. John Marshall Ferland, I think people should know more about him because he spoke in ways that depicted the constitution as a document that applied to all.

[00:23:17] He talked about being colorblind, a document that intended for citizens, regardless of ethnicity, gender, disability. Any other characteristic to be treated fairly and freely and equitably and our country in Brown I believe is a reckoning against Plessy v. Ferguson, a reckoning that we were anything but adhering to the documents talking about equality, like the founding documents and the 15th Amendment to the Constitution. So, I think young people in particular need to know the genesis of why a Brown v. Board was needed and Plessy v. Ferguson. It is, in fact, that genesis.

[00:23:58] Jocelyn Chadwick: You are so right. As you were speaking, the phrase kept coming into my mind when Harlan says that there would remain a power in the states by sinister legislation. And that is just, you’ve just explained that so well. to continue on this, the NAACP’s chief legal counsel, Thurgood Marshall, called John Marshall Harlan’s Plessy dissent his Bible and legal roadmap to overturning segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. Would you share with us your family’s interactions with the NAACP, Thurgood Marshall, and the legal preparation for this landmark decision?

[00:24:38] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Yeah, I, first of all, let me say that I, Justice Marshall is somebody I greatly admire, and I have his photo from the postage stamp hanging here in my office. One of the things I believe he meant, just, is that the law was really the foundation for social change. If you change the law, it makes social change possible.

[00:24:58] And that was in fact true, because once Brown v. Board was announced, it made possible the movement towards social change that we saw after. Now, Justice Marshall was not someone our family interacted with, again, one of those misnomers and there’s so much out there and social media and the internet certainly doesn’t help our cause because people come up with things they believe must have happened without actually knowing.

[00:25:24] And but my father never met Thurgood Marshall. My mother heard him speak when he came to Topeka to speak to an audience of people about all of the activity of the NAACP and in particular the cases. That’s it. That were being organized, but she was one in the audience, didn’t interact with him. He did stay in the home of Lucinda Todd, who was the secretary for the NAACP.

[00:25:47] And Lucinda Todd was, in fact, the first plaintiff in Brown v. Board of Education. Because she was at the meeting when they came up with the strategy and immediately volunteered. not like the internet would have you believe. We did not have a personal relationship, nor did my parents ever actually meet Thurgood Marshall.

[00:26:08] Jocelyn Chadwick: I thank you for that clarification, but as you said, his influence and his impact affected all of us, and that is special. to continue, In May 1954, the U. S. Supreme Court issued its unanimous 9 0 decision in favor of plaintiffs in five cases they consolidated from Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., ruling that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal, quote, unquote, and therefore laws that impose them violate the Equal Protection Clause. of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Please share your perspective of this decision and how this historic event in U.S. history still resonates with you personally.

[00:27:01] Cheryl Brown Henderson: I think the biggest takeaway is that Supreme Court decisions end up being simply a beginning of a conversation. People on the winning side are happy, excited, and they speak of change and implementation. People on the losing side are Disgruntled and will do everything they can to obstruct, deny, reverse, ignore, refuse to comply.

[00:27:30] And Brown v. Board is a quintessential example of that, because on the one side, the NAACP, even though it was measured enthusiasm, and that was true in our community and in our church and NAACP meetings, it was really cautious. Optimism that in fact, this would move forward in a forthwith manner, but on the other side of that conversation, we have people across the South who were gearing up for pushback.

[00:28:00] We have people in the United States Congress who were gearing up for pushback. The Southern Manifesto emerged out of the United States Congress, about a hundred elected officials from the South. Saying they were going to work to reverse the court’s decision, saying that it was judicial overreach, saying they were going to do everything in their power, and that any school district planning to defy, basically, they would support that.

[00:28:24] Massive resistance across the South within three years after the decision was announced. I’m saying all this to say that very few school districts immediately Complied. Now, Kansas was one of those states. Topeka was a city that immediately complied. May 54, court announced its opinion. In the fall of 54, schools desegregated in Topeka. And even some of the African American educators were moved into formerly all-white schools. The only thing that happened was principals for one year, if you had a black teacher in your building for the first time, were charged to call all white parents at that grade level to make certain that they were okay with having an African American teacher for their children.

[00:29:08] It was only something that they did for one semester because no one said no. So, we’re living in the aftermath of this conversation because those that really wanted to push back on Brown are still pushing back on Brown. Those who believed it was the way forward are still trying their best to make it the way forward and to bring us all together around the intent of the decision very complex, very difficult, not a straight line. This was not a linear decision where we decide and then going forward in a straight line, all these things happen. Far from it. And I think we’re still there.

[00:29:48] Jocelyn Chadwick: You are so right. And I just have to tell you, I was in that generation, as I said, that benefited later from what your father and others did. And, in Texas. So, I was in the South. And you’re right, it was unequal. some. Some schools did have that integration and tried, others didn’t, so I’m glad that you took your time to explain that and make it very clear that we’re still in the midst of all of this shift and strum and drum. Thank you for that. Let’s move on. The court’s Brown decision’s 14 pages did not spell out a method for ending racial segregation in schools. And the court’s second decision in Brown 2 Ordered states to desegregate, quote, with deliberate speed, unquote. Would you tell us more about Brown 2 and states resistance to the Brown decision? And that’s where you were going when you were just finishing up the previous one, so you can continue on.

[00:30:45] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Yeah, when you think about Brown 2 with all deliberate speed, that the courts giving the implementation decision, if you will. Disappointing, and you almost wonder if it’s laden with some sort of message, because the word deliberate is an odd choice. Deliberate, if you bother looking up the definition in any dictionary, it is a word that means slow.it doesn’t mean deliver from the standpoint that you go out there and you get it done right now, which is what I would say. People that don’t understand the definition think it means, it doesn’t mean that at all.

[00:31:24] So when you talk about anything with the little ration, if you think about the derivative of the word, it is painstaking, slow, methodical, all of that. But to Southern heirs, I believe it meant. Don’t hurry, don’t bother. So it’s interesting to me that particular choice of words, and of course we have no way of knowing why the court, the Oral War and Supreme Court, decided that was the word that would be the lynchpin that would make the difference, because that was the word that I believe Emboldened the Southern Manifesto and emboldened massive resistance in Virginia and everything that we saw after that.

[00:32:05] There are many other words that may have put us in a better position. When you talk about the part of the decision that Chief Justice Earl Warren read, he actually read a much longer part of the decision. But for whatever reason, and here we go with the media yet again, they picked up on That last part of what he read, which is, in the field of public education, the doctrine of separate but equal, and then he goes on to say that separating African American children caused a badge of inferiority in ways likely never to be undone.

[00:32:41] And it bothers me that is the part of the decision that was picked up and repeated decade after decade, when in fact, the earlier part of that very paragraph talked about the significance of education. That education is the most important act of state and local government, and that no child can be expected to succeed in life without the benefit of an education, and where it is provided.

[00:33:06] It is a right. They use the word right, RAGHT, that must be provided in unequal terms. I personally believe that may have moved us forward a little faster had we focused on the significance of education and then taken a look inside of what was happening with African American children. Why was it they were not getting, that world class education that schools are supposed to deliver, yet white children were?

[00:33:34] It may have been a whole different dialogue about how do we correct that error. But when we got into the mode of court order desegregations, because people were not complying, we got into the mode of busing, we got into the mode of counting heads, who’s sitting next to who, and that became problematic. And I think it’s still problematic because it opened the door to white flight. It opened the door to schools remaining segregated, largely because in counting those heads, white parents did not want their children to be in certain settings. The onus, sadly, then was placed on African American children and families. For this big implementation with all delivered speed.

[00:34:20] Jocelyn Chadwick: Oh, this is a really prescient conversation. We move to the final question. You’ve supported various successful school reform models in traditional school districts, charter public schools, and METCO style desegregation efforts that have delivered. Excellent results, 70 years after Brown, how would you like to see politicians, the courts, and policymakers address the racial inequities still found across American K-12 education?

[00:34:52] Cheryl Brown Henderson: First, I think they need to come clean. There needs to be an honest understanding and an honest conversation about what are the inequities.

[00:35:00] And the inequities we hear now are about outcomes. The inequities we hear now are about failing underfunded public schools, and sadly we have accepted the rhetoric of failure without challenging or pushing back and asking to explain how is that possible that a public school can be underfunded? How is it possible?

[00:35:25] That a public school, supported by all of us, can be a failing entity. So I think that we have, let me just say this, propaganda is the most powerful tool of any government at every level. More powerful than any weapon, if you can convince people of certain things. And I believe we have been convinced that our public school system is in fact failing.

[00:35:51] Now, rather than really asking the hard questions and demanding accountability, yes, I think that everything you mentioned, the other modes of education that have emerged, although school choice was a method of pushback after Brown, I’ll mean something different now, but I think every method that has emerged is all about trying to address.

[00:36:12] Something that we shouldn’t be accepting in the first place. We shouldn’t be accepting any idea that public schools can be legitimately considered failing and underfunded. But I will say, we cannot keep losing generations of children, which is why there is support for these alternative methods that are non-traditional to traditional public schools have been more accepted. But I still think the goal, the prize is education, and we need to redouble our efforts to define that and to make sure that all of our children are actually receiving that, a genuine education, and where there are disparities based on dollars, those disparities need to be equalized. Where there are disparities based on quality, that can be addressed by additional teacher training or shifting teachers around that need a little more support.

[00:37:10] This is not rocket science, yet we pretend it is. And we act in ways that we convince people that, oh my good, this is just not something we have any control over, not something we can do, when in fact that is 100 percent not true. And it should not matter the color of the child in the classroom. Because the goal is education, and children, teachers, and administrators, and school districts educate the children that show up where they show up.

[00:37:41] And I know in instances where that has been problematic, what you mentioned earlier has come in. In order to make sure that we don’t continue losing other generations, but boy, we need to roll up our sleeves, have a heavy conversation, and face reality. Because I think that we cannot afford to destroy public education.

[00:38:02] We just can’t afford that. Because it’s where the majority of our children live. And where the majority of us were educated. And then, the last thing, people also seem so willing to believe this rhetoric, because they believe that public schools are predominated by children of color, when they are not. If you look at the U.S. Department of Education website, and you look at the demographics around school children, I think African American children are 15 percent of public education students.

[00:38:34] Cheryl Brown Henderson: It’s not a high number, but the rhetoric again, the propaganda again, that leads you to believe otherwise and makes people more willing to accept a lackluster performance on the part of how we educate our children.

[00:38:49] Jocelyn Chadwick: Sadly, I agree with you. And it is, it’s for me, it’s a nightmare that I keep having every now and then. I’m thinking, what are we going to do to stop the skid? And you and I are definitely on the same page there. Thank you so much. I appreciate that.

[00:39:04] Cheryl Brown Henderson: You’re very welcome. And let me do say this, though. I will congratulate what Massachusetts has been doing. Until people step up, in the public arena, then, yeah, things have to be done. And don’t get me wrong, I congratulate the successes that they’ve had, but it just really saddens me. And it makes me angry, really, when we know that we can and should be doing better.

[00:39:28] Jocelyn Chadwick: I agree, and I was thinking about Massachusetts when I gave the last question about METCO, because METCO is such an amazing program. And in so many ways, people who are native to Massachusetts accept it. But for someone such as myself, coming from outside the state, seeing how METCO works, I am always in awe that in this day, it seems that there’s something that works.

[00:39:54] It’s not that it can’t be made better. Everything can be made better. But METCO is this jewel that I never even conceived could happen. It takes me back to all of those field trips and access and equity that Texas did at one time have in its educational system. And yeah, I, thank you for talking about Massachusetts. I wasn’t going to say it, but since you opened the door, I thought I’d go there.

[00:40:23] Cheryl Brown Henderson: I’m always happy to talk about these issues, and we can continue to, it shouldn’t just be a dream, it should at some point be. An opportunity for the entire nation. And my big soapbox issue is how we appoint secretaries of education. We hope could set an education agenda, but they’re never there long enough to really see it through. When you look at every four to eight years, we’re changing the guard. And then on the ground, school districts are expected to shift to the new platform. So someday we’ll wake up to the realities that we’re not doing our children any favor.

[00:41:00] Albert Cheng: Cheryl, that was great. Thanks for being on the show with us.

[00:41:03] Cheryl Brown Henderson: Oh, you’re very welcome.

[00:41:16] Albert Cheng: That takes us to the end of our show, but before we close out, I want to give the Tweet of the Week. This week’s Tweet of the Week comes from Ed Surge. It reads, At T Mobile’s Project 10 million initiative provides free internet to US K-12 students to help bridge the digital divide. Learn more about how eligible families and teachers can sign up here.

[00:41:39] And there is a link on that tweet, Jocelyn, I don’t know if you have thoughts about this, but it seems a neat initiative that T Mobile is doing to offer broadband internet to folks that don’t quite have access to it.

[00:41:50] Jocelyn Chadwick: Oh, I think it’s critical. I’m really glad that they’re doing that.

[00:41:53] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Yeah. So, if you know somebody that might benefit from this, refer them to this and there’s an opportunity to apply. Also, if you’re an educator or a school leader that’s listening. I think I saw on the website there a link specifically for you folks, how you might be able to get your schools involved, so check that out.

[00:42:12] Jocelyn, thanks for being on this show, it’s great to co-host with you.

[00:42:16] Jocelyn Chadwick: I really enjoy it, and with this particular topic, it is close to my heart, and so thank you for having me, it’s always an honor.

[00:42:25] Albert Cheng: yeah. And coming up next week, Jocelyn Chadwick’s going to be on a panel that the Pioneer Institute is hosting. It’s a webinar entitled, Civic Virtue and the Language of Democracy. That’s going to be Thursday, May 23rd at 2 p. m. I believe there should be a link for you to sign up and RSVP to that. Stay tuned for that and hear more from Dr. Chadwick and other guests on this important topic. Before we end, the last thing I want to say is that we’re I hope you enjoyed this week’s episode.

[00:42:54] Come back next week. We’re going to have Kimberly Stedman, who is the Network Co Director for the Brooke Charter Schools Network in Boston. So, hope to see you then, and until then, I wish you well. Have a great day.

This week on The Learning Curve co-hosts U-Arkansas Prof. Albert Cheng and Dr. Jocelyn Chadwick interview Cheryl Brown Henderson, daughter of the lead plaintiff in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education. She explores her family’s pivotal role in the Brown case, detailing her father’s part within the NAACP’s wider legal strategy. Cheryl discusses the influence of religious faith on the Civil Rights Movement, as well as the impact of segregation on her family, and their courageous decision to confront the legal barriers to racial equality in K-12 education. She emphasizes the ongoing need for comprehensive school reform leadership that will address the racial disparities still found across American public education.

Stories of the Week: Albert shared an article from Chalkbeat discussing the Newark Public Schools’ new AI tutor; Jocelyn discussed a piece in The Washington Post on how to help struggling third graders read.

Guest:

Cheryl Brown Henderson is one of the three daughters of the late Rev. Oliver L. Brown, who, with NAACP attorneys, filed suit against the local Board of Education. Their case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on May 17, 1954, and became known as the landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Cheryl is the Founding President of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research, and owner of Brown & Associates, an educational consulting firm. She has an extensive background in education, business, and civic leadership, having served on and chaired various local, state, and national boards. She earned a bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education, minor in Mathematics from Baker University, Baldwin City, Kansas, a master’s degree in Guidance and Counseling from Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas, and honorary doctorates from Washburn University and the University of South Florida.

Cheryl Brown Henderson is one of the three daughters of the late Rev. Oliver L. Brown, who, with NAACP attorneys, filed suit against the local Board of Education. Their case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on May 17, 1954, and became known as the landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Cheryl is the Founding President of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research, and owner of Brown & Associates, an educational consulting firm. She has an extensive background in education, business, and civic leadership, having served on and chaired various local, state, and national boards. She earned a bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education, minor in Mathematics from Baker University, Baldwin City, Kansas, a master’s degree in Guidance and Counseling from Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas, and honorary doctorates from Washburn University and the University of South Florida.

Tweet of the Week: