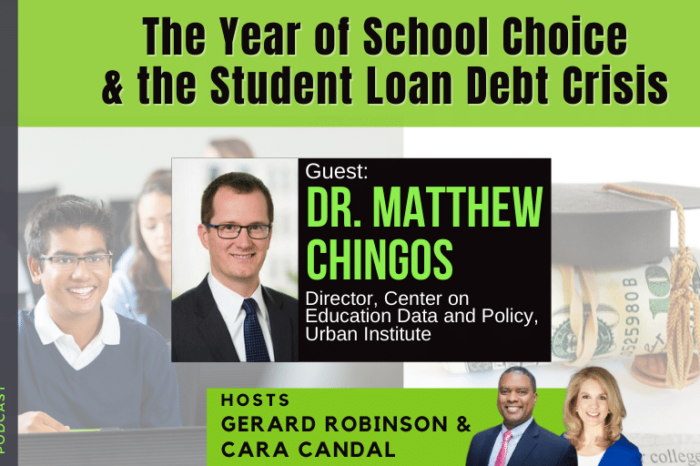

Urban Institute’s Dr. Matthew Chingos on the Year of School Choice & the Student Loan Debt Crisis

/in COVID Education, Featured, Higher Education, Podcast, School Choice /by Editorial Staff

This week on “The Learning Curve,” co-hosts Gerard Robinson and Cara Candal talk with Dr. Matthew Chingos, who directs the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute. They discuss the “Year of School Choice,” the welcome 2021 trend of states across America expanding or establishing private school choice programs. Dr. Chingos describes the gradual evolution of private school choice programs from primarily school vouchers to tax credit scholarships and education savings account programs (ESAs), which have been growing in popularity, and how charter public schools fit into this growing portfolio. He offers thoughts, as a researcher and scholar, on how using data to analyze, enhance, critique, and hold schools accountable for students’ academic improvements has transformed K-12 policy discussions, and how COVID-19’s discontinuities will impact accountability and decision making. They explore another topic of Dr. Chingos’ research, the $1.6 trillion student loan debt crisis, reasons why tuition has skyrocketed, and some of the possible pathways forward. Lastly, he shares views on issues of academic quality within higher education, and whether colleges and universities have lost their sense of mission.

Stories of the Week: In California, where only 32 percent of the state’s fourth graders were performing at or above proficient in reading, a proposed ballot measure is taking aim at those practices that protect ineffective K-12 teaching. Despite being the home of tech giants like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon, the state of Washington has reported that a mere 9 percent of its public high school students were enrolled in computer science courses during the 2019-20 school year.

Guest:

Dr. Matthew Chingos directs the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute. He leads a team of scholars who undertake policy-relevant research on issues from prekindergarten through postsecondary education and create tools such as Urban’s Education Data Portal. Chingos is co-author of Game of Loans: The Rhetoric and Reality of Student Debt and Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities. He has testified before Congress, and his work has been featured in media outlets such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and NPR. Before joining Urban, Chingos was a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He received a BA in government and economics and a PhD in government from Harvard University.

Dr. Matthew Chingos directs the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute. He leads a team of scholars who undertake policy-relevant research on issues from prekindergarten through postsecondary education and create tools such as Urban’s Education Data Portal. Chingos is co-author of Game of Loans: The Rhetoric and Reality of Student Debt and Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities. He has testified before Congress, and his work has been featured in media outlets such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and NPR. Before joining Urban, Chingos was a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He received a BA in government and economics and a PhD in government from Harvard University.

Tweet of the Week:

NEWS out of Detroit: The school district is moving to remote learning on Fridays in December to slow COVID spread https://t.co/6v8BX4JZJW via @ChalkbeatDET

— Lori Higgins (@LoriAHiggins) November 17, 2021

News Links:

Give every student access to computer-science education

A California Attempt to Repair the Crumbling Pillar of U.S. Education

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode

Please excuse typos.

[00:00:00] Gerard Robinson (GR): Hello listeners. This is Gerard Robinson from beautiful Charlottesville, Virginia. Welcome to another great. Upcoming conversation about education, about life, about social issues, and of course, a post Thanksgiving conversation about food. So Cara, how are you? How was Thanksgiving

[00:00:42] Cara: post-Thanksgiving torpor here, right?

[00:00:48] yeah, as I shared with you during it was, , a lovely Thanksgiving, in fact, we had very quiet sort of friends giving, which was just beautiful with people that we haven’t actually, had in the house in a long time. So [00:01:00] that was, , just marvelous. And then we resolve to actually relax on the Friday and Saturday after Thanksgiving, meaning like doing those things.

[00:01:10] When you should do like play board games with children and stuff like that. Then of course, my husband and I looked at each other Sunday night and we were like, we have so much to do. Why did we relax? So other realization, it was really wonderful to have that time with family and friends.

[00:01:24] And I got to say I’m off PI, again for the foreseeable future, because I don’t know, I don’t know if it was worth it. how about you? I want to hear about the beautiful meal.

[00:01:33] GR: So for those of you who listened last week, and this is also a hint, if you did not, you may want to go and check that one out.

[00:01:40] So we would hold with the family, just, , , my wife and I, and the two of three daughters. And I clicked this fried chicken. Now for most people, they’re like, wow, it’s nothing spectacular. Well, my family. Does not eat a lot of fried food. We eat some but not a lot. So this is the only, the second time in the life of my children ever had fried chicken.

[00:01:58] And both times I’ve made [00:02:00] it. So as many of you know, I’m also a pescatarian, I’m a vegan who eats seafood. Although for the last four months, I have really much gone plant-based here and there with, seafood. But anyway, so I had my vegan sausage, but I decided to try a piece of my own chicken. Now get this it’s the first time.

[00:02:20] I’ve had fried chicken since 1989. It carried you weren’t even born then. And so it was just a really different time in American life. So I had it and I think I had a tie moment that you just discussed. So let’s just say that won’t happen. But my family. I finished the last batch of cold chicken last night, but it was just good to be with family and friends.

[00:02:44] And we look forward to having people over next year. , we’re on the, other side of what we still have as a pandemic. So we can get that. Sorry.

[00:02:52] Cara: Are we on the other side of it? Because if you listen to the doom and gloom, I don’t know. I don’t know. I’m trying not to listen to the news anymore. I, one [00:03:00] important question though, drug, before we get to stories of the week, and that is will your Thanksgiving.

[00:03:05] I feel like that’s really important. I think it says a lot about people to know , what they serve as side dishes.

[00:03:11] GR: we had colored greens, we had yams and we had, Frye. cook the fries. We don’t have to branch potatoes and my wife bought something. Oh, we had macaroni and cheese, but of course, uh,

[00:03:23] Matt: yeah,

[00:03:25] Cara: delicious except for the soy cheese.

[00:03:27] Yes. Traditional answers. That sounds amazing. Okay. now I’m ready now. Rippling, you can go onto the story of the week. You have my permission.

[00:03:33] GR: Well, my story of the week is about. Other home state, which is California, as many of you know, I grew up in California, moved to the east coast for education work and love.

[00:03:43] And on the other side of California, there is conversations about California love or possibly California dreaming depending upon what artists do. So my article was from the wall street journal. Andy Kessler is the author and the title of his piece, a [00:04:00] California attempt to repair the crumbling pillars of us education.

[00:04:04] As we know, California is the largest state in America. It is a state that is a textbook adoption state. And so of course, when it happens in places like California, Texas happens across the United States. Well, the author here said California, like many states. Even pre pandemic, we’re having academic challenges.

[00:04:23] So for example, take this only 32% of fourth graders in California before the pandemic were at or above proficient in reading only 19% of eighth grade Hispanic. Read at grade level and only 10% of eighth grade black spirit. This was of course pre pandemic and some of our guests that we’ve had over the last several months, we’ve talked about the pandemic through the lens of financial as a politics realism curriculum.

[00:04:51] They’ve said we have something called learning loss with both you and I believe is reality. But that was pre pandemic. And so the question now is, [00:05:00] well, what do we do to basically help the golden state? Well, the golden state has been a recipient of billions, of dollars of federal money, through multiple stimulus packages.

[00:05:10] So that’s one lane, but there’s someone in that state who said, well, money matters, but how you spend it matters and how you spend it, particularly on quality education matters most. Oh. And by the way, Teachers play a role in that. So there is a entrepreneur in Silicon valley name, Dave Welch, who may be familiar to some of our listeners.

[00:05:29] He played a role and with others in 2014 in having Biguera V California make its way through the court system. And as some of you know, they basically said, listen, until we can find a way of getting rid of teachers that aren’t performing well or laying off teachers, for similar reasons. We’re going to have a lot of challenges.

[00:05:51] So it went before a judge in 2014, the judge ruled in favor of the families who brought the case. Well, in 2016, the [00:06:00] appeal court reverse that case and why they said quote with no proper showing of a constitutional violation. The court is without power to strike down the challenge statute, even though the court of appeals mentioned that a lot of the challenges in schools, in fact, teachers have played a role in that.

[00:06:18] And so Mr. Welch is pretty much back to where he started. And so he and a group of people have gotten together and said, listen, the education system that we have right now is not going to prioritize students for a holster reasons. One, you’ve got the teacher’s union, which in 2012, Was the fourth largest investor in 2020 elections, behind healthcare industry, , energy and prison guards.

[00:06:44] And so he said, let’s do something novel. If in fact what we propose was not a violation against the constitution. Why don’t we come up with an idea to say, basically we’re gonna make. Education a right in the state of California, it’s going to be a right. It’s going to be a [00:07:00] constitutional right. And if we make it a constitutional right, we’re going to basically say is that they’d be a high quality education that every student in California should have access to it.

[00:07:10] And if they don’t have access to it, Then you violated the constitution, whereas you, and I know we had a conversation about this as well. Recently, there was a ballot initiative in California to get with, uh, now the sitting governor, , nuisance to replacing with someone else. Well, he won that pretty handily and a 70 to 30 ballot vote vote that was put before the voters by a ballot initiative.

[00:07:33] Well guess what? California is a state where a lot of. That were signed and put before voters became law. Well, this could be another one. So Wells realizes basically it’s going to, he’s going to have to get, a million people to sign a petition. , it’s going to cost millions of dollars to do so.

[00:07:49] In fact, he estimates it’s going to cost around $8, an investment per signature, to get it on to the ballot, but he thinks it’s important. And why [00:08:00] he said until you make this a. And that high quality is a part of it. It’s going to be really tough to challenge the system. And as you and I both know, California has been involved in a number of, , let’s say, school finance decisions, going back to, , the, Serrano decision back in the 1970s.

[00:08:17] But we also in 19, no, 1973 Supreme court said that there is no federal constitutional right to educate. So over the past several years, there’ve been advocates and scholars, one being professor Kimberly Robinson from university of Virginia, who is the author of a book on the federal right education. And another book that looked at, school finance laws.

[00:08:37] And she’s been a guest on the show as well. They’ve been pushing to say, listen, if we can’t get it done at the federal level, guess what? Let’s talk about a constitutional right at the state level. So Mr. Walsh and his friends are going to move forward. They’ve already filed the paperwork. I bet he’s going to get a million signatures on the ballot is going to go before the voters.

[00:08:56] We’ll see what happens, but I can tell you one thing that will happen at the [00:09:00] 0.1 million people. So. And it’s going to find itself on the ballot. We’re going to have a really very tough but needed conversation about what high quality means and what does a right. Interesting education.

[00:09:15] Cara: My thoughts are well, many.

[00:09:17] I think first of all, a lot of our listeners might be surprised to hear that not all of our state constitution. I think, a lot of folks who are in the ed space know that there’s no federal right to education, that we leave it to the domain of the states. And that’s what the Supreme court has ruled.

[00:09:32] in fact, isn’t mentioned in the U S constitution at all, right? not the context we’re talking about. but that states, people think would be surprised to learn that states haven’t codified right to education in many places. I mean, we can even talk about international treaties that, , the us took the lead.

[00:09:49] I think it was under Eleanor Roosevelt in saying that for. Parents have a right to essentially direct the upbringing direct to the education of their children. We violate that, , on the daily [00:10:00] here in the U S by locking parents into single district options. But there, it’s interesting to the point you make Gerard this conversation around, what is it right to education now you hit on, if we can get the right to education codified, if we can get that put into California’s constitution, another state’s constitution.

[00:10:19] The debate over what constitutes quality. That’s something that. , I had a little bit of here in Massachusetts when we went through our Massachusetts education reform act back in the very early 1990s. , the thing that piqued my interest, Gerard, and I would love to talk to, your better half your other half about this is , how are we going to find access?

[00:10:37] Because if I hear you correctly, we’re talking about access, , that you have to have access. If education is indeed a right and. Access to what is access to a certain public school enough? Do you have to qualify how that school performs against? Against a state standard that may or may not need a [00:11:00] definition of quality.

[00:11:00] So, some states as you point out have been going through this for years, but it sounds like this is a renewed part of the debate. We’ve gone from arguments, , decades ago about equality of education, which raises questions do we mean equality of opportunity or equality of outcomes. And then we go to arguments around adequate.

[00:11:18] what constitutes an adequate education in here? I think you might be talking that adequacy sort of quality thing goes hand in hand, but then what about access? And if I need. To a certain kind of school to give me a specific quality of education and that’s different from the kind of access you need.

[00:11:37] Then I think that we’re having some really, really interesting conversations to your point. Now I’m hopeful that a case like this or a ballot initiative like this can drive the conversation forward. It usually. in state courts where , , we see huge pushes forward in education reform and Boyle boy, is it time because it’s, the nineties, when we saw a rash of [00:12:00] cases in places like Massachusetts and Kentucky and Texas, it’s a long time ago now, Gerard.

[00:12:05] , and so I’m really eager to see where this goes. I was going to say interesting, but it’s actually not interesting. It’s actually not very surprising that this is, a CEO, somebody in the business community, who’s driving this conversation because there’s also a history of that. And this country, as far back as the 1980s, when business owners started realizing that our schools were graduating, kids who didn’t have basic skills.

[00:12:27] That they needed to be even employable. So yeah, this is one to watch and maybe we’ll have to have Kimberly back on, help us understand some of the intricacies. we’re going to keep it on the west coast with my story of the week. And unlike you and my friend, I don’t get to say that I’ve lived in every state pretty much in this great country.

[00:12:47] I did spend a lot of time. Many years ago in my mid twenties when I was working in large-scale assessment. so this was like actually like 2001, 2002. Working in [00:13:00] large-scale assessment, in the state of Washington and working with the office of the superintendent of public instruction there, otherwise known as OSBI to help them create their first state tests.

[00:13:09] it’s a place that is near and dear to my heart because I got to spend really beautiful summers there. but today this article is coming to us out of the Seattle times and it’s entitled. I love it because it’s. Give every student access to a computer science education. So again, that word access, this is really particularly about computer science.

[00:13:29] And I think that this is another thing I’ve been digging into this a little bit lately, so it wasn’t super surprising to me, but it might surprise a lot of listeners to know the computer center. Arguably a skill that kids should have when they graduate high school is not something that we’re teaching in schools.

[00:13:43] And if we are, in some cases, we’re probably not doing a very good job of it. So, , Washington, like Boston is a bit of a technology hub. And according to this article, despite that status most public school districts in Washington, in fact, more than [00:14:00] 40%. So almost most aren’t even offering a single.

[00:14:05] In computer science. So what do we mean by computer science? I mean, there’s a couple of things we should understand that maybe sort of basic data and coding. I think data science is something that kids really need access to really need to understand it to, graduate high school. We should probably be thinking about that, , in terms of math curriculum as well, but also, , computer science, you can talk about, digital literacy, digital citizenship, some might call it like, how do we behave?

[00:14:29] Online, how do we behave with computers? I think that’s all part and parcel of it, but in the state of Washington and in so many states like it, this just not, it’s not happening in our schools and I’m not even talking high schools, it should probably be happening even earlier. so listen to this only around 30,000 students, that’s just under 9%.

[00:14:50] Of Washington’s high school students were enrolled in computer science courses during 20 19, 20 20. And you know, that dropped off way down during the pandemic. I’m sure. But [00:15:00] this one kills me of that number of that 9%, only 25% were female. Okay. Also underrepresented where students with disabilities, English, language learners, and students living in poverty.

[00:15:12] So. Again, not surprised by this, but I continue to be disheartened. , not only by the overall numbers, but the numbers for women, the number for, , students with disabilities, all of these populations that we’ve listed here, because we seem to keep, on the one hand, we have these stories about, for example, oh, women are going to college at higher rates than men.

[00:15:31] Like all of this. But I read stories like this, and I think we’ve got a long way to go because this tells me that we’re still not making the headway that we need to. And for all students and particularly for women in places. Stem. So this is going to be one to watch. I hope that we can spend more time in than your future Gerard talking about, , reinvisioning , the skills kids really need to have to go out into life, into the workforce, into college and career.

[00:15:57] Because I think that, just like the conversation [00:16:00] about access to a high quality education, this is something we haven’t been talking about near.

[00:16:05] GR: One of the reasons we put our girls in coding at age four each is to get them into a mindset of thinking or in thinking framework about how to assess.

[00:16:19] Thoughts ideas. How do we move? How do you think as someone say, they’re too young for coding, I said, first of all, you could start at four and then where we were at the time of Richmond. But more importantly, it’s a process of learning how to think, how to use your hands at an early age, how to manipulate, , objects.

[00:16:36] And they ended up building a small robots that would move around the house and they loved it. And then. Young ladies now, but because of what you said, you and I both know that it has been for a host of reasons. They’re just not as many women in computer science compared to other stem fields. But computer science has really been a challenge.

[00:16:56] And so glad to hear that I’d like to brag from the Virginia [00:17:00] perspective, because usually Massachusetts is way ahead of in areas like this. But in Virginia, in fact, we actually have the K-12 computers. Of course opportunities outlined, which we provide, or the department of education will provide to concerts and teachers and families.

[00:17:16] In terms of a pathway you can take in Virginia, to, study computer science, Virginia tech, which is in the Southwestern part of the state is still one of the top 10 producers of engineers in the country. we have a lot of technology companies in Northern Virginia. So computer science is a part of our DNA.

[00:17:35] I can’t tell you that it’s equally distributed across the state because it’s not in the, Southern part of the state and the Eastern part. Even some of the central parts where I live, it’s a challenge. So I’m glad you brought this up and I’m glad you highlighted computer science because we often say stem, but we don’t actually desegregate.

[00:17:53] the section, what is, what does that

[00:17:54] Cara: mean? Exactly, exactly. Gotta be able to explain it, gotta be like this, playing it to my mom, for [00:18:00] example, you know what exactly is stem? All right, Gerard, listen, we’re gonna pivot here because we’ve got a great guest waiting to come online. We’re going to be speaking with, , Dr. Matt Chingos.

[00:18:09] He directs the center on education, data, and policy at the urban Institute. And boy, if you read anything in ed policy, I bet you you’ve read his work. So we’ll be back.[00:19:00]

[00:19:23] Listeners we have with us today, Dr. Matthew Chingos. He directs the center on education, data, and policy at the Urban Institute. There he leads a team of scholars who undertake a policy relevant research on issues from pre kindergarten through post-secondary education and create tools, which this is a good one.

[00:19:40] So go check it out, such as the Urban’s education data portal, she goes to his coauthor of game of loans, the rhetoric and reality of students. And crossing the finish line, completing college at America’s public universities. He has testified before Congress and his work has been featured in media outlets, such as the New York times, the Washington post and [00:20:00] NPR before joining urban Chingos was a senior fellow at the Brookings institution.

[00:20:04] He received a BA in governance and economics and a PhD in government from Harvard university, Dr. Matthew, Chingos welcome to the learning curve.

[00:20:12] Matt: Thanks for having.

[00:20:13] Cara: Yeah, we’re excited. my first question for you, actually, Gerard and I were talking about just, I guess, two weeks ago. Now we were both at the national summit on education, hosted by Xcel and ed, where I, in fact, moderated a panel called the year of choice.

[00:20:29] And, I want to ask you about this because, if we look at the number of programs past and really what happened in the wake of the pandemic in terms of expanding. Private school choice options, even some charter school and open enrollment options in places. it was a big deal. So you’ve been looking at this stuff.

[00:20:46] You’ve been observing choice policy debates for a while. talk to us about what you see, what you saw in 2021 with the establishment of all of these.

[00:20:57] Matt: Well, obviously the pandemic appended so [00:21:00] much in American education with schools being entirely closed for a period of time and then moving to a mix of in-person virtual hybrid options.

[00:21:08] And in a lot of cases, families, weren’t totally, weren’t satisfied with. Available to them, especially if they had to work and needed a place for the children to go to school or just one of their children to be, engaged in a different environment. So I don’t think it’s a big surprise that, , there was kind of an increase in interest in choice, in 2021.

[00:21:25] if. Both the declines in enrollment in, traditional district schools. but also the charter school lines recently put out a report showing there is an increase in, charter schools, right? A former public education that didn’t save by and large, that fall off. So in my mind, it’s not surprising that you’d see more families looking for alternatives to the default one that many may have relied on in the past.

[00:21:46] And that may have a little bit of a push to some policy makers to, put in place some new policies, open up new opportunities, but I think what that looks like longterm, what the implications are really remained to be seen. there’s obviously still so much uncertainty. So to see how much of this is going to kind of [00:22:00] stick and reflect kind of a, a longer term demand beyond the kind of pandemic situation, versus how much of it might be more of a blip.

[00:22:09] Cara: Yeah. I want to push on that little bit, because a lot of these new programs that we’re talking about here, when we talked about private school choice and passing it, I do want to talk about charters tool, but we talked about private school choice in the past. We were mainly talking about.

[00:22:22] traditional vouchers or in many cases to get around Blaine amendments, tuition tax, credit scholarships, but the majority of new programs that were passed this year, or all education, some call them education, scholarship accounts, some call them education savings accounts, but these are accounts, right?

[00:22:36] That you can use them for private school tuition and a lot of cases, but really provide parents. a lot of the flexibility, would argue that many. Ooh, wealthy people can afford during the pandemic, right? Like supplemental services and tutoring and all of that good stuff. Now you say time will tell, I wonder if you can talk a little bit about, , are there any particular challenges, risks that you [00:23:00] see associated with the growth of this particular brand of private school choice?

[00:23:03] And by that, I mean, education savings.

[00:23:06] Matt: looking at the numbers, education savings accounts are still, as you know, relatively new, relatively small portion, I think in 2021 less than 30,000, , students with education savings accounts and compared that to over 300,000 with tax credit scholarships over almost nearly a quarter of a million , with school vouchers, you noted some of those new programs.

[00:23:24] So clearly that’s a number that’s going to, grow. You also noted how that additional flexibility was especially useful during the pandemic when suddenly if, at least for a couple of months, every family in America was suddenly a homeschool family, right. Was, you know, having to educate their students at home and obviously getting in many cases, handouts or virtual learning from their school district or from their school of any kind.

[00:23:44] , so think the value of. Being able to, have some resources to pay for, a range of educational opportunities. made all kinds of sense. , once again, to go back to the time will tell line, we’ll have to see is as there’s kind of more and more normal in [00:24:00] person, schooling options.

[00:24:01] including public schooling options, , will the ability to trade that for an account where you can buy a bunch of different things, will that be as appealing? I’m guessing some of this will stick, right? I imagine there were families who never thought that that would be of interest to them and then say the pandemic happened and it’s like, oh, it’s actually worked pretty well for my family.

[00:24:19] Whereas other families probably were like, , after a few months, That was more than enough , and happy to go back to some of the options they had before. So, so in my mind, there’s no doubt that that trend of growth is going to continue both because of the new programs and because of just the way pandemic has upended things and make people realize, maybe things they didn’t realize before.

[00:24:37] but to what degree we see that, , I think remains to be seen.

[00:24:40] Cara: Yeah, I have to add to what you’re saying with saying, personally find it really interesting to think about, how can we push on this concept of an education savings account for children, for families who might choose to stay in the public system?

[00:24:52] Is there something to learn there? We’ve seen it small programs in a couple of places, and then here’s what I’m going to wrap in charter schools, because we’ve seen. A [00:25:00] couple of charter schools, notably, two here in Boston that I know of. And, some in Oklahoma that are essentially saying we’re going to use federal money to give kids the equivalent of a small education scholarship account.

[00:25:13] Right. So you’re going to, you can be enrolled in our school, but we’re going to give you some money to provide supplemental services for your kids. And you can choose from a range of options that we’re going to vet for you. what are your thoughts on that? And could you also comment in there on.

[00:25:26] we’ve been hearing a lot about private school choice, but to your point, the Alliance just research saying that yeah, charter school growth is steady and up. where are charters going to fit in to this sort of expanded choice land?

[00:25:37] Matt: going to the question about, , education, savings accounts, but within the public system and the sense of, or including families who choose to keep their child enrolled in a public school, whether that’s a district school or a public charter school or a magnet school, but to supplement those educational opportunities with what’s private tutoring, with other things, and I think that’s obviously, you know, possibility and something, I’m sure a lot of families , [00:26:00] would value.

[00:26:00] I think there’s a question of, to what degree do you provide benefits to families? Especially if you’re targeting families with lowering. that are restricted, this pen on a particular thing versus just providing a cash. And obviously we see that playing out in debates about programs like snap, you know, the food stamp program.

[00:26:14] Like, should we, do we make, give people money or do we give some people and money they have to spend on food. And that’s kind of the same thing here. Do we get people money in the form of say an expanded child tax credit, which is obviously a priority for the current administration? or do we give them money?

[00:26:26] They have to spend on something in particular. in this case, education, think there’s also a way for, that kind of approach to help support choice within the public sector. And that comes back to your question about, charter schools and, obviously charter schools. Aren’t tied to the neighborhood that you live in.

[00:26:43] They kind of break that link between neighborhood and school attendance. And I think we generally see that as a good thing. But we know families are often limited in the neighborhood that can afford to live in. And if you break that link and say, you don’t have to go to your zone school, you have more opportunities that could potentially open up more higher quality opportunities, but they still have to get there.[00:27:00]

[00:27:00] Right. And geography is still a real constraint. And that if there aren’t appealing opportunities, you can actually get your child to, because you don’t have a car because public transportation is too expensive or because you just don’t have the time in your day to travel across town every day. I think this is here.

[00:27:14] We’re providing some additional resources. Families, because they could use for transportation could turn a choice. That’s a choice on paper, into a real choice for a lot of families and could be a way, , to expand the portfolio of options for families, both a traditional district, , charter schools, private schools.

[00:27:30] And what have you.

[00:27:31] Cara: I see why you testify in front of Congress. That’s answer. I’d like to capture talk to folks about, I want to. Take a little bit of a pivot here just because we’ve got you your work is about data and using data help us understand how to make better policy. one of the things we know to be true, and I was just talking with Gerard at the outset, how I used to work in standardized assessments, in fact, a large-scale assessment back in 2001.

[00:27:56] So when that’s what we were thinking about all the time and one of [00:28:00] the real. You might disagree, but would say of the no child left behind era is that we learned, how to actually use data, how to look at data, how to look under the hood and get at least 10,000 foot view of what was going on in schools, whether or not kids were being served.

[00:28:16] Today, I mean pre pandemic. And certainly it feels like post pandemic. The idea of test-based accountability, accountability generally, but test-based accountability in particular seems to be going out the window. , I feel like I have to share. I feel like I might be a little bit old school. my poor daughter is taking the independent school entrance exams right now and stressing out about it.

[00:28:36] And I keep telling her it’s a life skill. We need to learn how to do this. And in the back of my mind, I’m wondering, well, maybe it’s not going to be any more. I want to get your take on where you think we’re going in terms of not just accountability, but using large scale assessment for accountability and absent that.

[00:28:54] do we have any options for helping policy makers and in school leaders in, [00:29:00] parents make good decisions about.

[00:29:02] Matt: I think there’s a real tension here on one hand, I agree with you that the real value of no child left behind was shining a light on these issues and providing data both for students overall, but also for, subgroups of students based on income, based on race and ethnicity that we wouldn’t have.

[00:29:17] Otherwise, , it was obviously limited. It was limited in most cases to math and reading scores. So right. All these years later, people complain. Why do we pay so much attention to math and reading? Well, it’s because it’s what gets tested, but then you say, okay, so why don’t we test all these other things?

[00:29:29] Why don’t we test before third grade to get a better sense of sort of the development of early literacy skills? For example, then people say, well, whoa, whoa, wait a minute. I don’t, I think there’s too much testing or too little testing, but you sort of can’t have it both. ways there.

[00:29:40] so one hand really valuable, to have the information on the other hand, you know, do worry about, some of the effects on, whether it leads to too much focus on the things that are tested. and then whether there’s real, willingness to use the information and to act on it, , and to hold schools accountable.

[00:29:56] I think that was initially before. Palatable because the school wasn’t a person, right? It’s [00:30:00] this sort of vague institution to hold the school accountable. But once you turn that into now, let’s do let’s hold students and their families accountable. Let’s hold teachers accountable until principals account lollies or people.

[00:30:09] Right? So these are human beings with their strengths and weaknesses and promise and flaws and something like that gets a lot harder because right. You might look at a school and say, well, the test scores, aren’t so great, but it’s good in these other ways, do we really want to be punitive? , and is, , going after.

[00:30:23] Or, shaming schools for, posting bad scores, is that going to help them improve or is that just going to stigmatize them and make, things worse? And to be clear, we do have some evidence , that a lot of that accountability work did make a difference. , in terms of leading to some improvements in test scores, especially for students who , were fluid furthest behind before.

[00:30:40] Before NCLB, but as we , try to move sort of toward the future and kind of build on those gains, clearly nothing that has happened to solve everything, because we know we still have a lot of challenges we face. And this is a real question about what role, , standardized testing and accountability autoplay going forward.

[00:30:56] You know, in my view at a minimum, having the information is, really [00:31:00] important, but I think we probably need more, Then just the math look at math and reading in grades three through eight and once in high school. and we need to maybe rethink how we’re going to use that information to best support.

[00:31:10] GR: So Matt let’s switch gears and talk about higher education. As Cara mentioned in her opening, , you, , helped to co-author a book, the game of loans, and you’re pretty clear that your research has identified, 1.6 trillion in loans that are outstanding. And most of it’s held by the federal government.

[00:31:31] There are all kinds of politicians when they run for office, including. , during the 20, 20 presidential debate, what role will the new president play in the loan debate? Do we forgive loans? Do we come up with better rates? All these things. It’s a really big issue and I’m not sure people really understand how impactful it’s been, not only on the economy, but people who borrow.

[00:31:54] So talk to us broadly about the student loan debt crisis, how we got into it and what are some [00:32:00] possible remedies to.

[00:32:02] Matt: Well, it’s clearly a big issue that a lot of people care about a lot. As you mentioned, 1.6 trillion is a big number, right? What’s that 1,600 billion, which is. , I’m trying to do the math in my head to the mass, but it’s, it’s a lot of money.

[00:32:14] and part of how we got here is a good thing. It’s that more people are going to college, where people are getting bachelor’s degrees, more people are getting graduate degrees, and a lot of those are good investments that pay off for those people. So some of that growth is a good thing, the same way.

[00:32:25] If we encourage more people to get mortgages and become homeowners, and we saw mortgage debt go up, we’d say, well, that’s a good thing to the extent that we think. It’s a good thing. I think where the challenges are where people have, where some of that those dollars have gone to credentials that don’t pay.

[00:32:40] whether that’s, a degree from an institution that’s just not a very high quality credentials. It doesn’t actually help you be more successful in the labor market, whether it’s maybe a graduate degree that you were forced to get, because say you’re a teacher or a social worker. And, you know, we know in education, for example, that most master’s degrees don’t lead to any increase in teacher effectiveness.

[00:32:59] We in [00:33:00] many states require teachers to get them. So that’s not very good debt it’s that you took on, to get something that you just had to get for professional reasons. And then of course, lots of folks go to college, try it out for a couple of semesters, even a couple of years and doesn’t work out and they leave without a credential.

[00:33:13] And so now they have. From trying to get a credential, but they don’t have the enhanced earnings that would, where they would’ve gotten if they had earned the credential. So I think really the question is how do we do a better job of making fewer of the good loans, the good investments and making fewer of the bad loans and the bad investments.

[00:33:28] And there’s some, obvious problems with the program, , such as graduate students and parents of undergraduates can take unlimited amounts of money from the government. And obviously once you’ve started right , blank checks that. Can really cause all sorts of havoc and lead people to take on loans that they shouldn’t take on.

[00:33:43] , so just doing something about that while, , preserving the undergraduate loan program, which is more limited, and I think is, operated by the government in a much more responsible way. And then looking at the repayment side of. That having a safety net in place for people so that if you, , try out college and you have some debt and struggle to repay it, or if you don’t get [00:34:00] a great job right away, or a high paying job right away, you can pay back based on your income.

[00:34:04] And we have these programs in place, but they haven’t worked as evidenced by the millions of people in default. , so making the. Programs, work better for people. and then I think there’s some set of folks who took out loans that never should have been made because of a program that was designed by the government in an irresponsible way.

[00:34:20] And I think we absolutely ought to go forgive some of those loans, but we have to fix the problem going forward and backward. And those things have to work well together. If we just go and wipe out some or all of the day, And go back to making the same loans we were making yesterday. I’m sure the folks who get their homes for give them will appreciate that, but it’s not going to solve the policy program and it’s going to spend a whole lot of money.

[00:34:39] So I think we need to fix the program going forward and then say, well, what were the mistakes may looking backward? And let’s fix those by short for giving some of the debt for giving the loans that shouldn’t have been made. And then the folks who can afford to repay whose educations did pay off, have them be able to pay their loans in a way that’s affordable for them

[00:34:55] GR: sticking with higher education.

[00:34:57] her personal, take the loan and go to a [00:35:00] college. And we know that in the last 30 years, That the administrative costs in particular have just skyrocketed at colleges. And for many decades, higher education advocates have said, let’s just be honest. There’s a little relationship between, the increase in student tuition and the actual cost of delivering a college education.

[00:35:20] And there’s often, again, being paid for by a government loan. So discuss the role of higher ed and the role it plays itself in saddling generations of Americans with huge debt and who’s holding higher ed accountable for this and the first.

[00:35:37] Matt: folks like to talk about higher ed as if it’s the sort of, let’s say monolithic, but coherent, , organized thing.

[00:35:43] When, as you know, it’s a, a set of institutions of thousands of institutions, some private nonprofits on public, and the public’s obviously run by state governments, local community colleges, and then a slice of for-profit institutions. And these institutions are all operating in. And it’s not obviously a [00:36:00] completely free market.

[00:36:00] It’s a market that is, rife with support from the government in the form of both student loans, but also Pell grants that operate sort of as a voucher system and higher education. Let students can take that voucher in the form of whether it’s a grant or loan to. , any institution. And so within this market as strange of a market, as it is, , institutions, , have to, , act in a way that furthers their mission and furthers their interest as, institution.

[00:36:27] And so I think some of what you’ve seen is, for example, you know, in certain sectors of institutions, arms, races, around amenities, and maybe some of this is tied to administration as well. So I don’t think that’s probably the big, big cost driver here, but you’re trying to recruit students. So you have to go compete for them by offering better amenities or offering them.

[00:36:48] , , tuitions in the form of discounts and scholarships and things like that. So you can end up in a world where institutions are behaving in a way that makes sense for them as individuals. And if they didn’t act that way, they might go out of business or have financial [00:37:00] problems, but it’s not in a way that is particularly productive for higher education as a whole or for society.

[00:37:05] So I think the challenge for policy makers, especially Congress here, because they play such a role in the financing of this, but then of course, state governments as well. Is how do you change the set of incentives at play so that, the set of constraints that institutions face so that when they make these decisions, it leads to kind of a better outcome, overall, a virtuous cycle rather than addition.

[00:37:27] GR: Yeah, as we talk about colleges, we also talk about buildings and we talk about campuses and colleges have invested millions of dollars into the beautification of their canvas in part to attract. To attract, public and private investments, but also to keep up with some of their competitors. And while this is taking place, we also have a decline act, inequality, graded ablation, and the, those you say debates about political correctness on campus with all of this taking place, tuition going up in the air and [00:38:00] issues about competition.

[00:38:02] Are there some other issues that are driving? Costs and the image of higher education that maybe we’re missing and it starting to creep into the whole academic mission of education in the first place.

[00:38:15] Matt: an additional factor that I think drives cost here is just that labor costs in these service intensive industries have been going up over time.

[00:38:24] This is an issue in K-12 it’s an issue in higher education. Often called Bhamo bow and cost disease and Bumble and Bowen had this paper from the 1970s and they used example of a string quartet, and it always takes, , for human missions to perform a string quartet. , and that’s a model for the service sector of the economy and in , the more kind of capital intensive sector of the economy is that gets more productive over time.

[00:38:47] Due to developments around technology, people are, workers in those sectors and more productive. They have to get paid. And they expect to get paid more. They get paid more so to compete with that. The service side of the economy has to pay people more, even though productivity isn’t going [00:39:00] up because it still takes, , for people to play in a string quartet, , a teacher with 25 students or a professor teaching a lecture of 200 students, it’s still a person.

[00:39:09] And so that. That increase in labor costs, I think is probably a significant factor in both K-12 and higher education. It’s not obvious what you do about it. So I think what’s important to try and disentangle on some of these policy discussions is what are the cost increases that are kind of unavoidable.

[00:39:26] That cost increases that are above what we think of as inflation and this sort of consumer goods, CPI side, but our kind of labor. Inflation. And then what are the ones that seem to be more the result , of bad incentives around some of these amenities, arms races be on building fancy buildings, fancy dorms, , which, maybe are driving up costs in a way that are actually avoidable.

[00:39:46] Well,

[00:39:46] GR: man, I want to thank you again for joining us today. We’re talking about higher ed and K-12, we often don’t have people who can actually walk both lanes. well, and you did, and for talking about, you know, what this means for our [00:40:00] economy, , I’m a big proponent of school reform. I’m a big believer that money matters, but money alone, without a conversation about the context.

[00:40:08] Of schooling and how we invest and what are some of the bureaucratic and, , policy challenges in place sometimes makes this work tough. So thanks for joining us. And we look forward to future conversations.

[00:40:21] [00:41:00] So Cara, my tweeter the week is, , from your mom’s hometown of Detroit and your state of Michigan. And this is from Laurie Higgins, November 18th. The school district of Detroit is moving to remote learning on Fridays in December. It’s a slow COVID spread and I’ve heard some Detroit Chalkbeat I know that your, neck of the woods,

[00:41:35] Cara: it is such a, bummer, but right.

[00:41:37] , we’ve known, who’s going to happen is all of us who live in cold climates, we start to move indoors. And so our thoughts are. Families. Hopefully the district is better prepared than I’m guessing it is to go back to remote learning because I say that because I don’t think most districts are.

[00:41:53] but it’s going to be a reality probably for a lot of us into the spring and a hard pivot for parents and teachers [00:42:00] alike. So our thoughts are with them. I will say. And there’s also some pretty sad breaking news out of Michigan of yet another high school shooting just as we are recording this right now.

[00:42:09] So a lot of good luck going out to my home state. after a weekend, I will say when a lot of U of M fans at least had something to be joyful about, and that is, I don’t even watch football, but my phone was blowing up friends and families with this university of Michigan, victory over Ohio state, which hasn’t happened yet.

[00:42:28] And I guess like 20 something years. so that’s the good part, but our, thoughts and prayers. Families friends and the people of Detroit and good luck with remote learning teachers, parents, students, hopefully it won’t last long. All right, Gerard, we will be back together again, looking forward to next week when we’re going to have yet another amazing guest and you and I can begin to reflect on what a year it has been.

[00:42:53] So until then my friend, take care, talk to you next week.

Recent Episodes:

Joy Pullmann on the Fallout from Common Core

This Week on The Learning Curve: E.D. Hirsch, Jr. on Background Knowledge & Educational Equity

Steven Wilson on Anti-Intellectualism in K-12 Education

Jason Bedrick on Religious Freedom & Private School Autonomy

Dr. Lindsey Burke on LBJ’s True Education Legacy

NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut on State-Driven K-12 Reform

The Learning Curve: Andrew Campanella, President of National School Choice Week