Study Finds UMass Leadership – Not Campus Administrators – Bears Primary Responsibility for UMass Boston Budget Woes

University board approved irresponsible campus spending based on faulty projections, then required UMass Boston to replenish reserves

Read early coverage of this report in the Boston Herald and here, The Boston Business Journal , WCVB-TV, MassLive, the Dorchester Reporter. Bay State Banner, and Bloomberg Radio.

Contact Micaela Dawson, 617-723-2277 ext. 203 or mdawson@pioneerinstitute.org

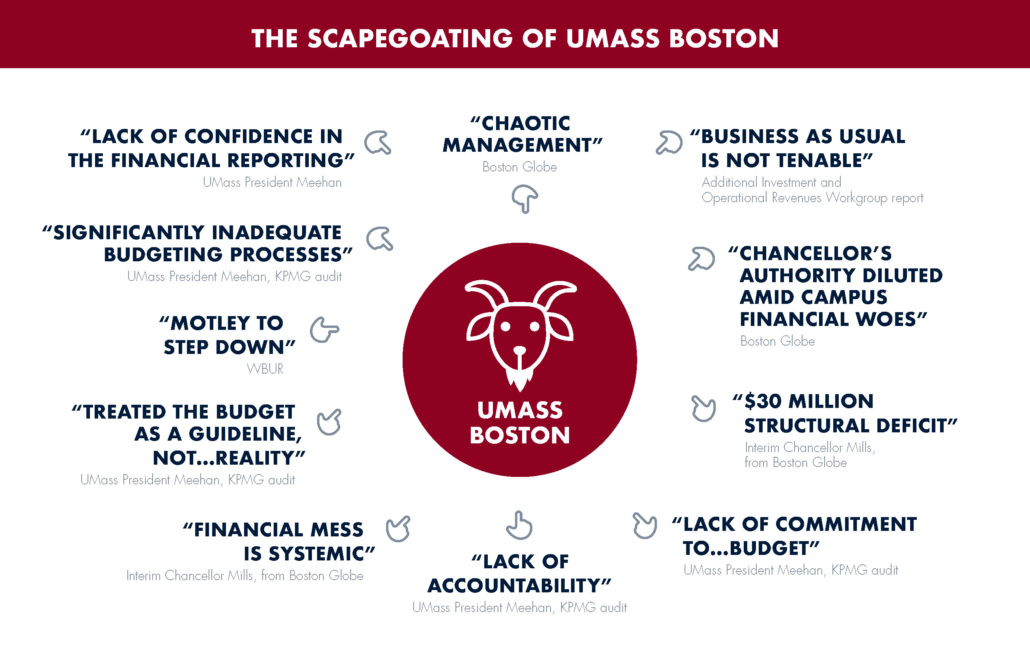

BOSTON – While the blame fell on former UMass Boston Chancellor Keith Motley, the UMass Board of Trustees and President bear the bulk of the responsibility for the recent budget crisis at UMass Boston due to a lack of oversight of the campus’s capital expenditures, according to a new study published by Pioneer Institute.

“A more accurate description of the UMass-Boston budget crisis is that the UMass Board of Trustees, President, and Central Office approved a program of rapid capital expansion and failed to plan for, provide, and keep track of the funds needed to pay for it,” said Greg Sullivan, co-author with Rebekah Paxton, of “Fiscal Crisis at UMass Boston: The True Story and the Scapegoating.” “When they realized their mistake in the middle of fiscal 2017, the crisis was triggered.”

When the campus was projected to have a $30 million budget deficit for fiscal years 2017 and 2018, UMass President Marty Meehan blamed it on Motley, who ultimately resigned his position after the UMass Board of Trustees refused to extend his contract.

Despite warnings about a looming financial crisis, UMass Boston ended FY2017 with a $1.1 million operating loss, and ended FY2018 with a projected $2.5 million operating deficit, according to audited financial statements. Both are significantly lower than the so-called $30 million deficit.

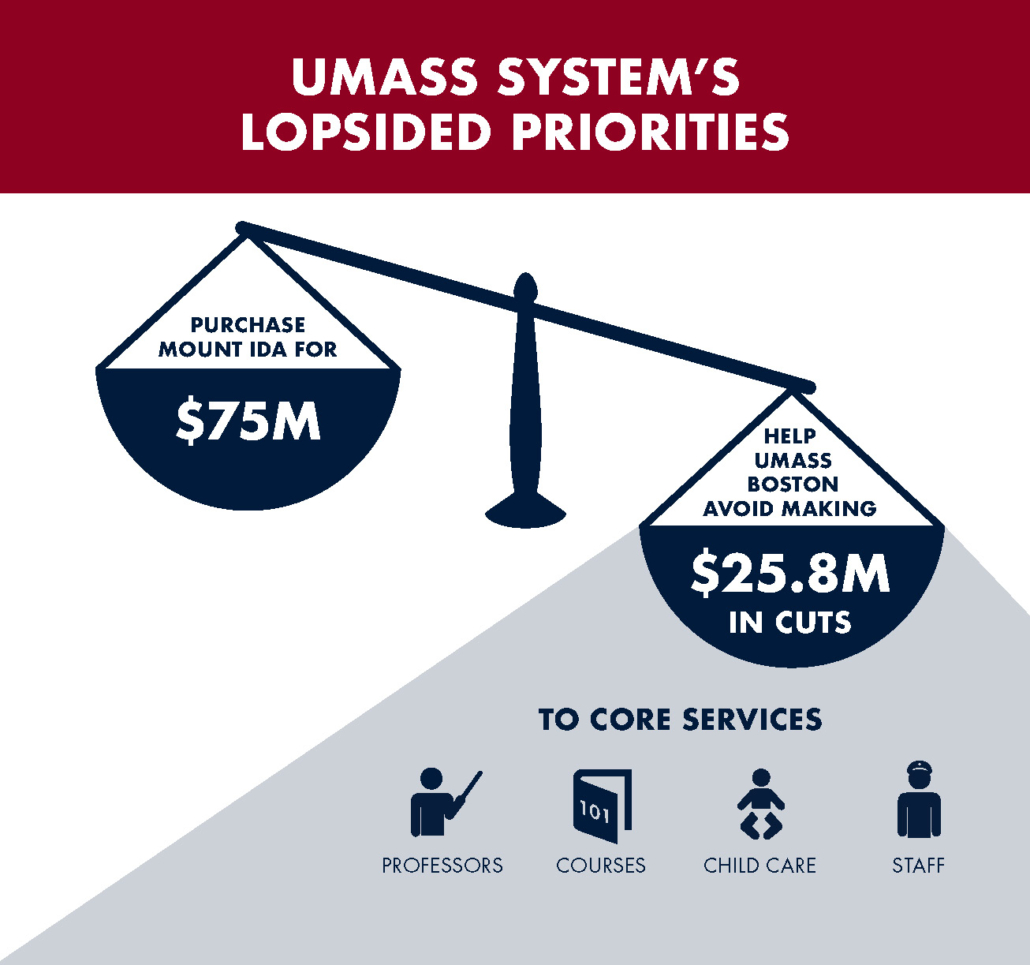

An analysis of annual budgets, financial projects, capital plans, and UMass Board of Trustees (BoT) meeting minutes reveals that upon realizing they had overestimated UMass Boston’s ability to afford capital expenditures that they had previously approved, the university’s BoT, president, and Central Budget Office directed Boston administrators to replenish reserves. The reserves had been gutted with the approval of the university’s central leadership. These public records show that $25.3 million of the alleged $30 million deficit can be attributed to a directive from the Central Budget Office requiring Boston leadership to restock the campus’s primary reserves.

This $25.3 million figure was originally presented as a depreciation expense by Vice Chancellor for Administration and Finance Kathleen Kirleis at a May 9, 2017 UMass Boston town hall forum. However, the board-approved FY2017 operating budget already included depreciation in its operating expenses and was nearly balanced, except for a $25.8 million delineation of “reductions needed to meet budget.”

To carry out UMass Boston’s strategic plan, the BoT and university president approved capital spending for a spate of expansion projects included in the FY2016-2020 Financial Projection released in April 2016, which the UMass Central Office later realized had been highly inaccurate (as reflected in the FY2017-2021 Financial Projection published several months later in September 2016), and that it would be irresponsible for the Boston campus to spend the vast majority of its reserves to fund the projects.

April 2016 estimates of UMass Boston’s available reserves were $77.7 million for FY2017 and $92.9 million for FY2018. By September 2016, these projections were deemed erroneous and reduced to $28.1 million for FY2017 and $28.5 million for FY2018, representing decreases of $49.6 million and $64.4 million respectively.

These depleted reserves would result in low primary reserve ratios, which are unrestricted net assets divided by operating expenditures. The ratios would have been 6.6 percent in FY2017 and 6.4 percent in FY2018, well below the UMass policy of maintaining ratios at 20 percent.

Records show the BoT voted to approve a dangerously low reserve balance of $27.9 million for UMass Boston in the FY2017 UMass Operating Budget. The board also voted to approve an even lower reserve balance of $12.1 million for UMass Boston in its FY2018 UMass Operating Budget.

The UMass President and board approved massive UMass Boston capital spending based on faulty projections, then required the campus to restore its reserves to increase its primary reserve ratio, which is often used as a tool to determine financial health.

State law and regulations provide that the board of trustees is responsible for approving the university budget, including operating and capital budgets for each campus.

“The university president’s office is responsible for assuring that sufficient resources will be available to fund the capital plan,” Sullivan said. “Despite this, university officials blamed UMass Boston administrators for financial mismanagement and poor planning.”

An audit commissioned by President Meehan in 2017 was limited to only certain procedures at UMass Boston. Without comprehensive reviewing capacity, the audit ignored issues around oversight and the role of the UMass Board of Trustees and President.

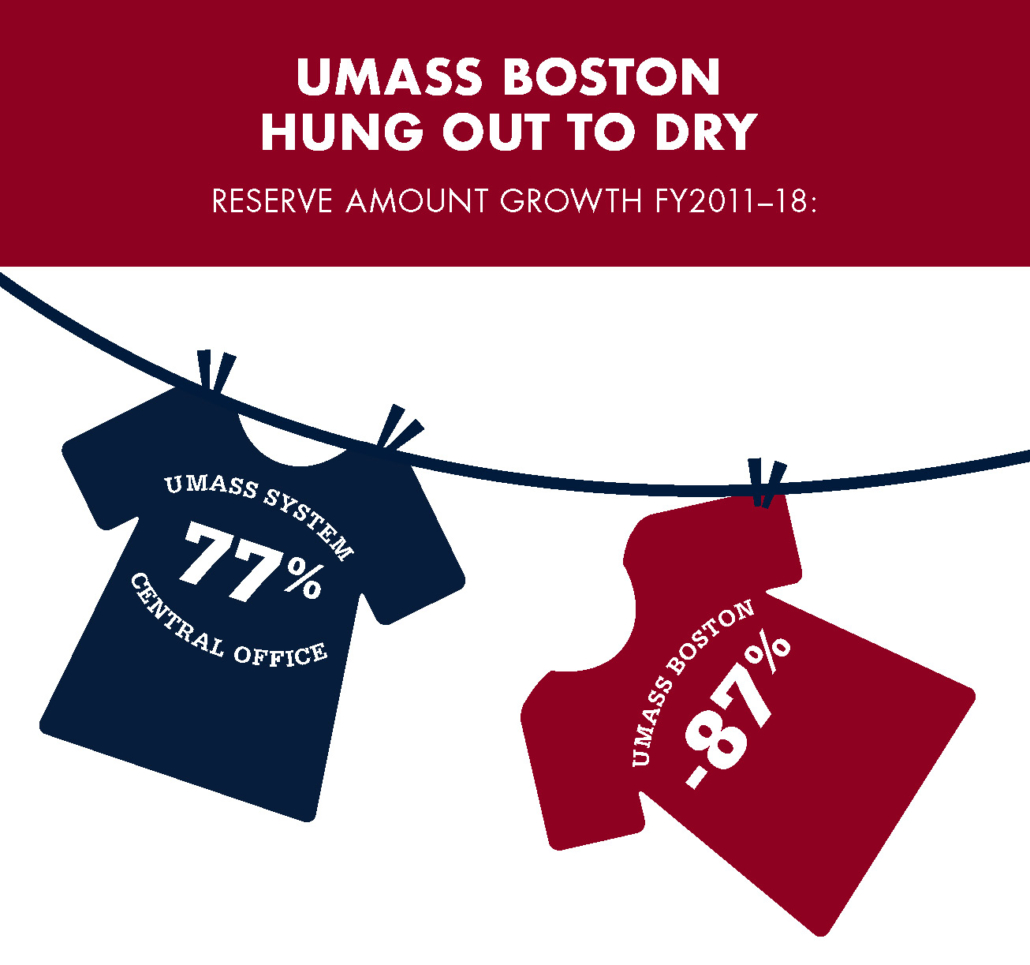

While the Boston campus was ordered to make drastic operating cuts – including faculty, staff, and course offerings – to replenish its primary reserves, other UMass reserve accounts were growing. Central Office reserves grew from $68.9 million in FY2011 to $102.1 million in FY2016, while Boston’s declined from $93 million in FY2011 to the board-approved $12.1 million in FY2018.

In addition, the April 2018 purchase of the campus of the former Mount Ida College in Newton for $75 million demonstrated that the university had the funds to help UMass Boston, but instead required it to endure financial hardship and allegations of mismanagement and poor leadership.

About the Authors

Gregory W. Sullivan is Pioneer’s Research Director. Prior to joining Pioneer, Sullivan served two five-year terms as Inspector General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, where he directed many significant cases. Prior to serving as Inspector General, Greg held several positions within the state Office of Inspector General, and was a 17-year member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Greg holds degrees from Harvard College, The Kennedy School of Public Administration, and the Sloan School at MIT.

Rebekah Paxton is a Research Assistant at Pioneer Institute. She first joined Pioneer in 2017 as a Roger Perry intern, writing about transparency issues within the Commonwealth, including fiscal policy and higher education. Since then, she has worked on various research projects in areas of state finance, public policy, and labor relations. She recently earned an M.A. in Political Science and a B.A. in Political Science and Economics, from Boston University, where she graduated summa cum laude.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.

Infographics

Get our higher education updates!

Related Posts