7 Reasons to Reject the Graduated Tax and Instead Focus on Growing Jobs

On April 27th, Pioneer Institute Executive Director Jim Stergios submitted public testimony to the Massachusetts Legislature’s Joint Committee on Revenue highlighting the Institute’s serious concerns about the proposed graduated income tax amendment to the Massachusetts State Constitution, and the detrimental impact it would have on the state’s economy as it begins to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pioneer has done deep research on this topic with a singular goal: Getting the 300,000 Massachusetts residents who lost their jobs or left the workforce since the start of the pandemic back to work. Pioneer is particularly concerned about the retail, restaurant, hotel/leisure and healthcare sectors, which were hardest hit by COVID and pandemic-related policies.

In Jim’s testimony, he shares seven reasons why the proposed graduated income tax amendment stands in the way of economic recovery:

Statement before the Joint Committee on Revenue

In Opposition to: HB 86 (Pages 1-4) A legislative amendment to the Constitution to provide resources for education and transportation through an additional tax on incomes in excess of one million dollars.

Thank you, Chairman Hinds, Chairman Cusack, and members of the committee for the opportunity to submit public testimony highlighting Pioneer Institute’s very serious concerns about how the proposed amendment to the Massachusetts State Constitution would have a detrimental impact on the state’s economy as it begins to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pioneer has done significant research regarding the impact of the proposed surtax on the state economy. Much of what follows may be familiar: As we analyze data from the Internal Revenue Service, the Massachusetts Department of Revenue, Bureau of Labor Statistics and dozens of other sources and reports, we are sharing the findings with you. As a 501(c)3 educational foundation, interested in robust and rational civic engagement, the Institute has a mandate also to provide the broader public with an objective understanding of the real-life impacts of tax proposals under consideration by the legislature. To accomplish that part of our mission, Pioneer has worked to gain several hundred appearances in national, regional and Boston news outlets; we have also made a point of communicating our findings directly to our 350,000 email and social media subscribers, through op-eds, infographics, videos, webinars, podcasts and more.

Our goal is simple. There are 300,000 Massachusetts residents who were in the workforce in February 2020 but who are no longer working in April 2021. Many worked in the retail, restaurant, hotel/leisure and healthcare sectors, which were particularly hard hit by the pandemic and pandemic-related policies. We want them back to productive work, earning and saving money, paying their bills and investing in their futures. With that context, from the research data we have analyzed thus far it is clear that there are seven reasons why the amendment would run counter to our goal of regaining full employment.

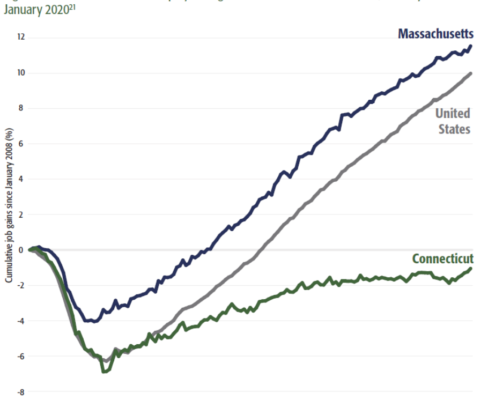

1. We would be unwise to embrace a policy that has done so much damage to our next-door neighbor, Connecticut.

We must draw lessons from the devastating impact raising taxes has had in Connecticut. After raising its income tax to 6.99 percent, the Constitution State proved unable to regain the jobs lost in the 2009 recession. The Connecticut state budget only grew by 22 percent since 2008. Over the same period, Massachusetts’ job growth outpaced the national rate and funded 63 percent growth in the state budget. The lesson learned: Job creation is good for everybody, including state budget writers. Democratic Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont said the tax increases “totally disadvantage the state,” noting that it already has “some of the highest income tax rates in the country and we pay a price for that.” His point is not that raising federal taxes is always a bad idea, but rather that raising state taxes puts state economies at a disadvantage.

2. The suggestion that the wealthy do not leave high-tax states is wishful thinking and demonstrably false.

-

-

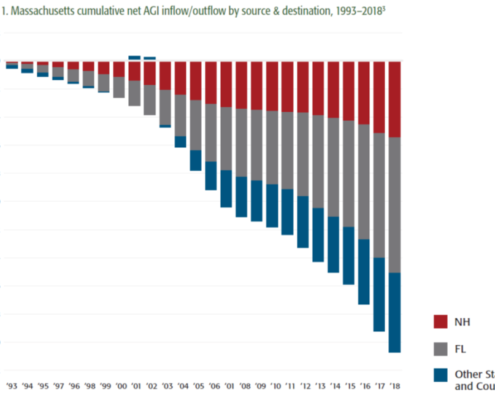

- From 1993-2018, Massachusetts has seen almost $1 billion annually in wealth leave the Bay State, with 70 percent of that outmigration to Florida and New Hampshire, two no-income-tax states. To be specific, Massachusetts experienced a net outflow of $21 billion in adjusted gross income (AGI) from 1993 to 2018, with nearly half of it going to Florida. The level of outmigration was especially significant from 2012 onward. We believe the impact of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act limitation on state and local tax deductions, which took effect in 2018, has likely exacerbated these trends further, but we do not have that data available to us yet.

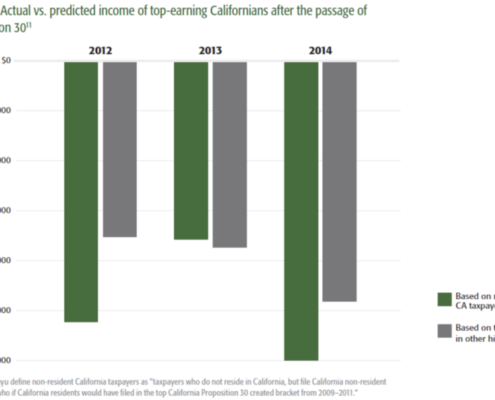

- If you look at California’s high-earner income tax hikes, they generated a lot less revenue than was promised, because people left. California’s tax on high-income households led to a spike in outmigration of businesses and residents that “eroded 60.9% of [new] tax revenues by [the law’s] second year.” We all know about the litany of big companies that left California, but also hard hit by the tax were pass-through businesses, which pay taxes through the individual returns of their owners, rather than through company returns. Because of its harsh tax climate, in the words of Elon Musk, California “has a forest of redwoods and the little trees can’t grow.”

- The argument that the proposed tax will have little impact on the mobility of high earners is riddled with self-serving definitional errors and exclusions (they actually exclude the majority of millionaires). For example, the work of Cornell University Associate Professor Cristobal Young, which has been cited by tax proponents, counts only those earning $1 million in the year before they moved, ignoring those who move in anticipation of earning a seven-figure annual income from the sale of high-value assets. Considering the fact that, according to IRS data, over the decade that ended in 2017, 46 percent of Massachusetts residents who earned $1 million or more in a year did so only once, that’s a big exclusion. Young also fails to consider the hundreds of thousands of Massachusetts households with net worth greater than $1 million that earn less than $1 million annually. Finally, Young ignores the role of tax policy in attracting migrants to Florida, which does not have income, capital gains, or estate taxes. He treats Florida as an outlier, claiming that “when Florida is excluded, there is virtually no tax migration” in the U.S. As Greg Sullivan, former Massachusetts Inspector General and today Pioneer Institute’s research director, has noted, “That’s akin to saying that if you exclude Muhammad Ali, Louisville, Kentucky hasn’t produced any great boxers.” Finally, even Young concludes that 2.4 percent of millionaires move each year. Even without accounting for Professor Young’s underestimation of millionaire household migration, the cumulative effect of an annual loss of high-net-worth taxpayers can add up to big numbers over a decade or more.

-

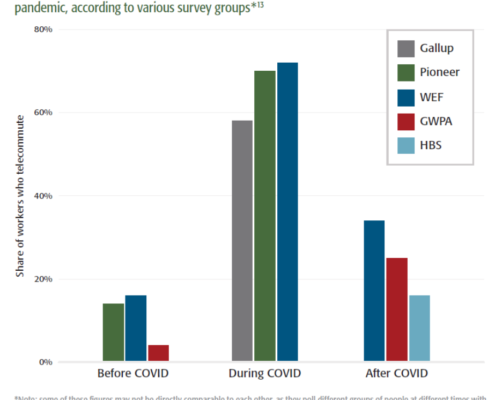

3. The proposed constitutional amendment to create a graduated income tax would make it even more attractive for companies to take advantage of lowered barriers to exit after the pandemic to relocate employees out of state. With the pandemic, barriers to exiting high-cost states are lower and companies may therefore be more willing to have employees working at a distance. With the rapid embrace of technology and telecommuting, high-quality surveys project 30 percent of employees at Massachusetts companies will be working from home post-COVID (up from 4 percent pre-COVID). Telecommuting is especially attractive in industries where the workforce can be highly mobile and where cost-savings from remote work are greatest. As a result, we expect that tax and cost of doing business policies will have a much more significant impact on location and relocation decisions. In Massachusetts’ case, as we noted in a Boston Globe opinion piece, the implications of the potential Supreme Court case, New Hampshire v. Massachusetts, regarding state income taxes on telecommuters brought by New Hampshire (and now other states), are that the impacts of increasing taxes will become even more significant.

4. The suggestion that the proposed constitutional amendment to create a graduated income tax will lead to significant new revenues for education and transportation is unpersuasive.

-

-

- New revenue from a proposed surtax might not increase state education and transportation spending.Supporters of a graduated income tax claim that any new tax revenue will go to increase spending on transportation and education. But top legal minds, including lawyers on both sides of the 2018 Supreme Judicial Court case in which an earlier version of this proposed amendment was knocked off the statewide ballot, as well as the SJC’s chief justice at the time, all concluded that total state funding for these priorities could remain the same or even decline without violating the amendment. Although revenue from the proposed amendment would be required to go to these purposes, other revenue currently dedicated to education could be diverted. Thus, the would-be revenues resulting from the amendment would be fungible. Given that the legislature rejected two proposed amendments during the 2019 Constitutional Convention that would have dedicated all new revenue from the constitutional amendment to transportation and education, the revenues are most likely to go to the General Fund.

- After passage of a 2012 tax hike, California diverted what were supposed to be education investments to the non-education bureaucracy. The number of teachers grew by a fraction of 1 percent (that is not a typo) — and California was required by a separate constitutional provision to spend a minimum of new tax revenues on education. Massachusetts has no such spending requirement and, as noted above, the Massachusetts Legislature in 2019 rejected two amendments that would have required that new tax revenues go to education and transportation.

-

5. The proposed tax does nothing to help those who actually suffered the most during the pandemic. Massachusetts state government employment has been virtually flat during COVID-19, while employment in the state’s private sector workforce remains nearly 10 percent below pre-pandemic levels. The leisure and hospitality sector hasn’t surpassed 70 percent of pre-pandemic levels since last spring. Over the 12-month period ended January 31, 2021, the number of small businesses open in Massachusetts declined by nearly 38 percent.

6. The constitutional amendment to create a graduated income tax does not fall on millionaires; rather, it is a tax on retirement for tens of thousands of people and, because of its faulty “inflation adjustor,” over time on an increasing percentage of taxpayers.

-

-

- The graduated income tax proposal would raid the retirement nest eggs of Massachusetts residents by pushing households into a high tax bracket on the sales of homes and especially businesses. Data Pioneer Institute recently obtained from the Massachusetts Department of Revenue show that in Massachusetts, 46 percent of the people who would be affected by the tax – those who earn over $1 million in a year – did so only once in 10 years. Sixty percent did so only once or twice in the 10-year period ending in 2017. Most of these people are selling a business or a home. Nearly half the capital gains earned in the US from 2007-2012 were from pass-through businesses, usually small businesses that pay taxes via the personal income returns of their owners, another common source of retirement funding. Owners who sell these businesses to pay for their retirement will see their tax bills on those capital gains rise by 80 percent under the surtax. Proponents of the tax haven’t thought about the incentive it creates to change one’s domicile to low- or no-tax states as Massachusetts residents approach retirement, nor the deterrent it would create to investment.

- The graduated income tax proposal is poorly worded and locks in a cost-of-living adjustment that will lead to significant bracket creep. Proponents purport to use cost-of-living-based bracket adjustments as a safeguard to ensure that only millionaires would pay the tax. Historic income growth trends, however, demonstrate that bracket creep will subject many non-millionaires to the surtax over time. If Massachusetts incomes and prices continue to grow at present rates, households currently earning $700,000 a year (or earning $500,000 a year with the sale of an asset that has a gain of over $200,000 in value) will be subject to the surtax by 2038. Whether willfully or not, proponents of the tax amendment insisted on an escalation factor, the Consumer Price Index, that will be punitive to many more Massachusetts taxpayers than they claim. Tying the measure to median household income would have better protected taxpayers from bracket creep. Embedding the CPI in a constitutional amendment is not only incongruous with the rest of the constitution, it is bad policy that will be hard to correct, since it would require the constitutional amendment process rather than simply passing legislation.

-

7. The constitutional amendment to create a graduated income tax is a penalty on small businesses and will undermine the innovative start-up economy that depends on Greater Boston’s financial services industry for funding.

-

-

- The graduated income tax would adversely impact a significant number of pass-through businesses, ultimately slowing the Commonwealth’s economic recovery from the pandemic. If the surtax passes, it will apply to as many as 13,430 of the state’s pass-through entities. These are often small businesses structured as S corporations, sole proprietorships and partnerships that pay taxes via their owners’ personal returns. Proponents claim the surtax will only affect Massachusetts’ highest-paid corporate executives. In reality, many independent business owners will also be directly affected, including a lot of main street business owners. In 2018, pass-through employers accounted for 57 percent of Massachusetts’ private sector workforce. Nationally pass-through entities represent 95 percent of all businesses. Promoters of the surtax always point to its impact on some nebulous ‘millionaire.’ The tax will, in fact, impact many more people and small businesses, and through them, tens of thousands of employees.

- The graduated income tax proposal would undermine innovative start-ups that depend on Greater Boston’s financial services industry for funding, ultimately hampering the region’s recovery from the pandemic. If passed, the surtax will give Massachusetts the highest short-term capital gains tax rate in the nation and the highest long-term capital gains tax rate in New England. For the financial services industry, which employed more than 191,000 people in 2019, with 77 percent of those jobs located in Greater Boston, the tax would be devastating. For investors, there is a particularly punitive aspect of a graduated state income tax proposal: In Massachusetts, unlike at the federal level, capital gains can push you into a higher tax bracket. Sky-high taxes on capital gains will ultimately reduce the level of investment activity in the state. That matters not just to investors, but to the tens of thousands of people employed in Cambridge, South Boston and other areas that have enjoyed a remarkable economic renaissance driven by innovative firms. Our innovation clusters rely heavily on Boston’s strong investment industry. If we put that industry at a disadvantage, we will weaken our innovation clusters, the demand for products and services from industries that conduct business with our innovation clusters, and ultimately job creation.

-

There are many other reasons to oppose a constitutional amendment that creates a graduated income tax, including the short-sightedness and inflexibility of using the constitution to formulate tax policy. What I have focused on in the present testimony are the ways in which the proposal undermines what we believe is the prudent and most vital focus of public policy after the pandemic — getting those out of work back to work.

I am, again, grateful for the opportunity to submit written public comment.

James Stergios

Executive Director

Pioneer Institute

Get Updates on Our Economic Opportunity Research

Related Posts: