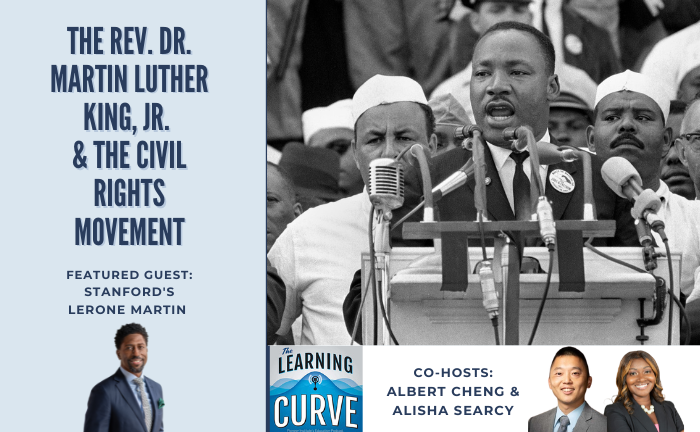

Stanford’s Lerone Martin on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. & the Civil Rights Movement

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Lerone Martin

[00:00:00]

[00:00:04] Albert Cheng: Well, hello again, everybody. This is Albert Cheng coming at you with a, another episode of the learning curve podcast and hosting this episode with me is Alisha Thomas Searcy.

[00:00:17] Hey, Alisha, what’s up? Hey, Albert. How are you doing? Doing all right. And this is our, our Martin Luther King day episode. It’s a big day in the country, isn’t it? That’s right, that’s right, and being on the MLK episode, we’ve got a fascinating guest, Lerone Martin, who’s gonna be talking to us about the life of Dr. King. But before we get to that part of our show, let’s chat news like we, we always do. So, what’s going on in, uh, what does have to be your corner of the world? What did you notice?

[00:00:47] Alisha Searcy: Well, I don’t know if you’ve been following this stuff that’s going on with the Chicago Board of Education. Oh, yeah. Oh, my goodness. What a saga they are in. The new mayor of Chicago, as people probably know, is a teacher union member. He was one of the leaders who became mayor. Beat the incumbent, big deal. And what a mess it’s been, frankly, since he’s been elected. As it relates to the board, he got to appoint board members, a bunch of them resigned, then more were elected.

[00:01:20] And so now this new hybrid board is going to be seated and there are a bunch of issues happening. And so this article is, I think it’s CBS. News, it’s the new hybrid Chicago board of education to be seated amid financial crisis, increased discord in CTU talks, either teacher’s union. And so they have a number of issues.

[00:01:43] They also, this board before the new ones come on, those who are appointed by the mayor just fired their superintendent who had been doing a good job by all accounts, but apparently the union doesn’t like him. They’ve been in. Talks, you know, over contract negotiations for a few months. And at first they liked him and then they decided they didn’t like him.

[00:02:07] And you wouldn’t believe this, but one of the reasons that the talks have broken down is the teacher union president compared the superintendent. to a special ed student that you can’t suspend. Oh boy. So I want you to think about that for a minute. The teacher’s union president, right, is comparing the superintendent to a child with special needs.

[00:02:30] So clearly there were lots of people who are very angry about that comparison. She has since apologized. I don’t even know if you can really undo that damage. It’s one of those. You can’t cry over spilled milk. It’s or the, you can’t get the toothpaste back in the tube. But the bottom line is they have a bunch of issues.

[00:02:48] They’ve got this contract negotiation going. They’re going to need a new superintendent soon. They’ve got this hybrid board of elected and appointed members. Oh, and by the way, they have a major financial crisis where the mayors. Solution for this was to get a loan. I don’t know if I’ve ever heard of a school district having to get a loan, especially not a big urban school district.

[00:03:13] So it’s a mess in Chicago public schools. And have you noticed of all the things that I’ve said, I never mentioned children. Huh? Yeah. And so that’s the problem, right? When you have adults who are fighting and they’re talking about contracts and all these other things. Who’s serving the children? So it was a tough article to read.

[00:03:33] It’s a tough issue to watch, but for those of us who care about kids all over the country, right. And making sure that we do this well, we’re going to have to keep paying attention to what’s happening in Chicago and how this all shakes out.

[00:03:45] Albert Cheng: Well, thanks for sharing that, Alicia. I hadn’t been paying attention to all the stuff that was going on there. Well, you know, I want to head a few states south of that. I saw an article about Louisiana and IDEA Charter Schools. I think you might be familiar with that network? Yes. It’s a pretty good one, at least, you know, from what I’ve heard. They don’t study that kind of charter school before as well. So yeah, I guess this is the story.

[00:04:12] I don’t know. I guess both of us have bad news. Maybe we should have coordinated better maybe today, but there were two of those IDEA charter schools in Louisiana. And apparently the story is that they’re closing and they haven’t been doing well. You know, they actually started off pretty well. They were established in Louisiana a few years before the pandemic. Did pretty well in Baton Rouge, uh, to be more specific. And then just since the pandemic, performance and student outcomes have really dropped. So it’s kind of leading to the closure of these two schools. So, you know, this has raised lots of questions about the access to high quality charters, just high quality schools for, for the students in Baton Rouge.

[00:04:50] So anyway, take a look at that story if you want to kind of follow what’s going on there. I’m not sure what to think about this as for the reasons why, you know, the news article makes kind of a big deal about some leadership failure and that might be part of it. You know, when I was reading the article, I was also reminded of our friend Steve Wilson’s work, you know, how he’s kind of pointing out how some charter schools that have, especially before the pandemic, Really held the line on holding high expectations, high standards for kids.

[00:05:18] Kind of eroded that line and lost the edge to keep those expectations up. And kind of got distracted. And, you know, I wonder if that was something that was going on there too, but, you know, I might be wrong. I just want to be clear, go on the record here. This is just. My speculation and it just certainly reminded me of some of the stuff that our friend Steve Wilson’s observed.

[00:05:38] But yeah, it’s, I think it’s a good hypothesis.

[00:05:41] Alisha Searcy: It’s always leadership, right? That’s a huge piece of it. And you know, we could name other networks that are not performing as we Are used to, right? So I think this is a problem happening all over the country among a lot of charter schools. And it’s a problem because we know that, you know, they’re supposed to be outperforming and they’re supposed to be doing well. And we don’t want more schools that are underserving kids.

[00:06:06] Albert Cheng: Yeah. So, well, hey, let’s see what happens, uh, in Louisiana and Chicago moving forward here. Hope for the best. Anyway, I guess that’s going to be a talk for another time. We want to get to our, our guest here, Dr. Laura Martin is going to talk to us about the life of Dr. Martin Luther King. So stick around and join us on the flip side of the break.

[00:06:38] Lerone Martin is the Martin Luther King, Jr. Centennial Professor in Religious Studies, African and African American Studies, and the Nina C. Crocker Faculty Scholar. He also serves as the Director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. Professor Martin is an award winning scholar of The gospel of J. Edgar Hoover, how the FBI aided and abetted the rise of white Christian nationalism. His commentary and writing have been featured on the NBC Today show, the History Channel, PBS, C SPAN, and NPR, as well as in the New York Times, Boston Globe, CNN. com, and the Atlanta Journal Constitution. He currently serves as an advisor to the upcoming PBS documentary series, The History of Gospel Music and Preaching. He earned his B. A. from Anderson University, an M. Div. from Princeton Theological Seminary, and his Ph. D. from Emory University. Dr. Martin, welcome to the show. It’s a pleasure to have you on.

[00:07:41] Lerone Martin: Thank you for having me. It’s a blessing and a privilege to be with you.

[00:07:44] Albert Cheng: Well, so let’s start. I mean, I guess, where do we start? You know, let’s talk about the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King. But let’s start here. So, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, they were Baptist ministers committed to nonviolent protests and what they called a soul force. Why don’t we start with having you share with our listeners how Dr. King was trying to provide larger spiritual and political leadership to the nation.

[00:08:14] Lerone Martin: For Dr. King, Soulforce was this power that tapped into African American Christianity, and it’s concerned not just for the hearts and souls of individuals, but actual bodies of human beings. And for King, This soul force was a way to combat the kind of violent force of racism and economic inequality and war.

[00:08:43] He believed that African American Christianity in particular, but Christianity in general, could provide resources. So that everyday individuals, whether you were, had a PhD like Martin Luther King, Jr. Or if you were not working at all and were not educated, he believed that the resources of Christianity and nonviolence could really endow people with the ability to change their circumstances to actually combat.

[00:09:16] The violence that they encountered every day via racism, via economic inequality, discrimination, segregation, and the outright brutality of Southern racism in the form of Jim Crow. So for King, it was this ability to marshal the gospel of Jesus Christ. It was the ability to marshal nonviolence and the belief that God was on the side. Of those pushing for justice and equality, all of these things were able to be brought together to combat the failures of American democracy.

[00:09:57] Albert Cheng: Well, you know, speaking of bringing things together and, you know, it’s been noted at various times during the civil rights movement, Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were leading and then other times it was students and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Could you talk a bit more about the relationship between Dr. King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee? And actually, you know, for that matter, you know, what was the relationship like with other less well known civil rights figures like late Bob Moses or Fannie Lou Hamer?

[00:10:30] Lerone Martin: It’s a great question. Overall, you know, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee really arguably, you know, you could say has its genesis. In the sit in movement, and after the sit in movements happened in Greensboro, North Carolina, and started popping up all across the country, all of these student activists were brought together for a conference, and Ella Baker was there to help them organize this.

[00:10:58] Budding organization of student activists. Originally, it was thought that the student nonviolent coordinating committee would be an organization under the auspices of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Ella Baker, someone that Martin Luther King Jr. knew very well. She had been appointed the interim executive director of King’s organization, but was never given the title of director.

[00:11:24] In part because she was a woman and she was not a minister. King knew her very well, and she knew King very well. She strongly encouraged the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to remain independent, to not have their organization be sussumed under the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

[00:11:40] And part of that was because Ella Baker is not a well known figure in the civil rights movement, but she is an amazing figure that I would encourage listeners to check out. Ella Baker was this genius when it came to community organizing. And she was concerned and she felt that Martin Luther King Jr. relied a bit too much on what she called and what scholars called community mobilizing. In other words, coming into a particular community, mobilizing people for a short term project and then leaving. She thought the best way to bring about change was for people in the local community who live there to organize for a long, sustaining change in efforts towards combating racism and economic inequality and police violence.

[00:12:35] So there was a difference in philosophy in many ways in terms of how King thought about mobilizing communities for change and Ella Baker thought about organizing. Now Martin Luther King Jr. certainly believed in local community organizations. He was, after all, a Baptist minister at one point in time in a local community, but his emphasis was on using his.

[00:13:00] increasing popularity and notoriety to bring attention to issues across the country. And that caused him to travel and to be engaged in mobilizing local communities and mobilizing media attention and financial resources. And Ella Baker and Bob Moses were more interested in organizing locally and organizing local people.

[00:13:24] They were concerned that having King have this model of mobilizing and flying in as a leader, they were concerned that It didn’t allow individuals to tap into their own greatness for individuals to believe that they can be leaders who can bring about change in their own community and not have to rely on a charismatic leader.

[00:13:46] So in that sense, while both of these organizations were committed to alleviating racism. poverty and war, they went about doing it in a different way. And in that sense, Martin Luther King Jr. and these groups, we don’t need to see them necessarily as antagonistic, but we can see them as complimentary.

[00:14:07] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Fascinating to think about the two philosophies there. I want to return to, you know, again, a theme that you’ve, you’ve been bringing up, which is, you know, how Dr. King marshaled his faith and not only that, but, you know, he had a deep knowledge of history, poetry, of course, you know, hymns and spirituals. We often reference, you know, Langston Hughes’s 1951 poem, Harlem, a dream deferred and how that influenced Dr. King’s sermons and speeches. So talk about how, how that vast store of literature and all those resources really inspired Dr. King and the movement on a larger scale.

[00:14:40] Lerone Martin: It’s helpful to think about Martin Luther King Jr. in some ways as an intellectual jazz man, you know, and his ability to improvise and pull from so many different genres in a way that to touch his listeners. So, for those who are part of the African American Protestant tradition, as you mentioned, he knew the hymns, he knew the certain sayings and colloquialisms, right, within the church about, you know, Getting saved, regeneration, right?

[00:15:09] You know, about the gospel songs that he would quote and even would have sung sometimes before he would speak. But King also was just so educated and schooled in sort of the American canon, if you will. He was schooled in knowing the Constitution, he was schooled in knowing the Declaration of Independence.

[00:15:28] And so for listeners who were moved by quote unquote American scriptures, if you will, he was able to marshal those texts to also show how the goals of the civil rights movement were in line with the Declaration of Independence, right? That he was not some type of Communists or maybe what folks would accuse him of today of being woke.

[00:15:49] No, his dreams and his efforts and his labors were a part of the American story. And so he was brilliant at bringing in American scriptures as well. And then he was brilliant and great at bringing in As you mentioned, poetry and other novels and famous writers in America, both black and white. And, you know, I’m working on a book right now on his teenage years.

[00:16:11] And what I’m discovering in this book, which will be for a general audience, and we’re also going to do a graphic novel, is that so many of his teachers in elementary school and middle school, many of which, which is important to point out, were women. Exposed him to the writings of Langston Hughes, exposed him to the writings of famous poets that there’s a local librarian, Miss Annie McPheeters, who tells a story that King would come into the local Auburn Avenue library as a little boy.

[00:16:43] And he would always want to show off to her the new poem that he memorized. He would come in and he would say a part of a poem and then stop and see if she could recognize what poem it was and finish it. And so even as a little boy, he had this love of words, this love of rhetoric, this love of poetry and novels and literature. And he marshaled all of that as an adult to show how it was in line with American ideals.

[00:17:12] Albert Cheng: That’s fascinating. I think about I’ll have to keep my eye out for that forthcoming book here to take a deeper look at his earlier formation, but, uh, yeah. Let’s talk Birmingham for a bit here. So for several years, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth worked to have Martin Luther King come to Birmingham, Alabama for direct action really in what many regarded as the most segregated city in the South. So share with us what we should know about Martin Luther King Jr. in Birmingham. You know, the participation of Reverend Shuttlesworth, the student protests there. And of course, I think most are going to be familiar with a letter from a Birmingham jail.

[00:17:48] Lerone Martin: Yes, and I really appreciate this question. As the director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, I am now the senior editor of the King Papers Project.

[00:17:58] Albert Cheng: Mm-hmm .

[00:17:58] Lerone Martin: And what this project does is to edit and publish King’s personal papers. And we are currently working on this moment in King’s Life right now, 1963. And I think the thing is, I’m reading these documents, letters, police notes.

[00:18:14] And police surveillance and sermons that King preaches and speeches he gives is I think what jumps out at me that I think we have not fully appreciated. And the way we tell the story is the amount of violence and the amount of opposition that the campaign in Birmingham was facing just in their efforts to desegregate public accommodations and to have African American police officers hired as a way to stop the police brutality.

[00:18:50] And I think what I’m just so struck by is that we often tell this story as the King goes, Bull O’Connor puts water hoses on people. He puts dogs on people. Eventually the Kennedy administration sees this. It says we have to stop this. It’s embarrassing on the global stage. And eventually, you know, the city fathers in Birmingham sit down and negotiate and it’s the end of story.

[00:19:17] But there’s so much more that happens there. The amount of violence that occurs during the campaign and after the campaign, people who are shot. People who are murdered. We know about the four little girls in Birmingham, right? Who died in the 16th Street church bombing. But there’s so much more violence and bombing that I think we just have not appreciated the level to which Birmingham was opposed to this, this simple desegregation of public accommodations.

[00:19:50] And I think the second thing that really jumps out to me as I’m reviewing these documents we’re preparing to publish Is that some of the sermons we’ve never heard before, we have access to that King was preaching while in Birmingham, not just the letter from Birmingham jail, but the daily addresses for the mass meetings he was giving to encourage people.

[00:20:12] Is how really, really committed to this. The King was, he, he knew that death was all around him. He knew the threats were coming in against him. The way that Bull Connor attempted to revoke all press passes so that the skullduggery he was engaged in cannot be chronicled by journalists and the podcasters of the day.

[00:20:34] And King still moved forward. I think that’s what is so striking to me that he didn’t know how this was going to end, but he kept moving forward. And the role, finally, I’d say, and the role of children, I think we have not appreciated as well the role of children in the Birmingham campaign, that when King was in jail and King was writing the letter from Birmingham jail, and after he was of course released, the idea about bringing children.

[00:21:02] And to bring children along, school children as young as eight and nine years old, to bring them into the nonviolent protest, which was James Bevel’s suggestion, was really, you know, a moment of young people realizing. The stakes and young people getting involved and really helping to push the needle towards justice.

[00:21:24] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Wow. There’s a ton more we could unpack there. Thanks for sharing that. And guess what, you know, for our listeners, we’ll say kind of, you know, keep an eye out for some of that work that you’re doing that you’re going to release soon. So appreciate that. Let’s move a bit ahead in the timeline here. And many of us are going to be familiar with the March at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington and Dr. King’s famous, I have a dream speech. And then, you know, a year later in 1964, he then won the Nobel peace prize. Could you talk about the significance of these events and the speeches that Dr. King delivered at them?

[00:21:57] Lerone Martin: I think the first thing I would say about the, I have a dream speech is that. What often gets lost is that the speech occurred at the March on Washington for jobs and freedom.

[00:22:08] Yeah,

[00:22:09] Lerone Martin: that’s right. I think what we have, we have not appreciated that there was an economic component. We hear today many people quoting the speech and they of course quote the speech where King says, I look forward to the day where my four little children, right, his fourth daughter was born in 1963.

[00:22:25] Where my four little children will live in a world where they’ll be judged, not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. And many people single that part out of the speech to make King a mascot for a kind of colorblind America. But if you listen to the rest of that speech, it’s not about a colorblind America.

[00:22:43] It’s about recognizing the way that racism and color has been used to. Elevate some people, and to demean other people, and to divvy up resources. And what King says in that speech is that America has written the Negro, he would say at that time, a bad check that has come back insufficient funds. But we don’t believe that the Bank of Democracy is bankrupt, right?

[00:23:09] So for King, it was so much about the United States living up to what it said on paper as it relates to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and making sure that every citizen had the right and had the ability to pursue the American dream. I think we haven’t appreciated the fullness of the I Have a Dream speech, especially when given in the context of it was at the March for Jobs and Freedom, that it was so important.

[00:23:34] And part of the demands, if you go online and Google this, you can find the demands of the March on Washington. Part of it is for increasing the minimum wage. And then you can do the equivalency online to the Bureau of Labor Statistics about, I think they were asking at the time for 2 an hour. for the minimum wage at the time to be raised up.

[00:23:55] So it’s important to recognize that King was advocating not just about racism, but also economic inequality. And then, of course, the speech that he gives when he wins the Nobel Peace Prize that he gives in 1964. What’s so powerful about that speech is that he mentions And his speech, and as well as his Nobel Prize lecture, that the danger is that we have allowed our technological progress, he says, to out distance our moral progress.

[00:24:25] And King even mentioned then about computers, machines that talk and cars and weapons. have advanced that allow us to do things we never thought were possible. But yet our moral progress has not kept pace. And I think that’s just a warning for all of us that King gave all the way back in 1964, that we need to make sure that our moral commitments and our moral progress in the country, from our elected officials to our local officials, to people living everyday lives. That we need to make sure we have a commitment to morality as well as moral progress as well as a commitment to technological progress.

[00:25:09] Alisha Searcy: Wow. Dr. Martin, in looking at your name, it feels like maybe you were destined to do this work. It’s really powerful to hear your voice answering our questions and I can only imagine what it was, what it is like to be this close to all of the sermons and his papers and just reading about history and a lot of things we probably don’t know.

[00:25:32] And so it’s very clear that you are deeply connected to Dr. King and clearly are a fan. But the truth is there are some people right throughout history who were not. And so I want to call your attention to talk about what it was like for Dr. King. In dealing with the government, there’s a quote, you don’t fire God in quote by President Kennedy, reportedly, he said, when asked about removing J Edgar Hoover as FBI director, can you talk about JFK and LBJ is dealings with Hoover, including the bureaucratic leverage he wielded over them, and his illegal wiretapping of Dr. King and figures within the civil rights movement.

[00:26:18] Lerone Martin: Yes, I mean, you, you, this is an important point that I think that we have to talk about that, you know, while King has a statue on the National Mall, right? He’s the only person that’s not a president with a statue on the National Mall. He’s an individual with his own holiday.

[00:26:35] That can lure us into thinking that America always loved him. And that America was always behind him and that America always recognized that he was an icon and a leader. But the reality is that Martin Luther King Jr. was under surveillance and there was a campaign against Martin Luther King Jr. from 1963.

[00:26:59] The FBI was very deliberate about this after the March on Washington and to his death and the FBI both laundered intelligence and gave it to other ministers for other ministers to put in their sermons and to work against Martin Luther King Jr. and specifically Reverend Elder Lightfoot Solomon Leshaw.

[00:27:21] It also tried its best to get other church organizations against Martin Luther King Jr. by saying then purported intelligence about him. Now all of this was based on the FBI having the ability to wiretap him and also put bugs in his hotel rooms, which Robert Kennedy gave them permission to do this. On October 10th of 1963, because the FBI was making claims that King was a communist.

[00:27:52] That King today, I guess we would say he was a socialist or he was woke. And I think the FBI made this claim, even though the FBI records show us that they did not have sufficient evidence that King was a communist whatsoever, or that the communists had control of the civil rights movement. Now, there were two individuals in King’s inner circle.

[00:28:16] One by the name of Jack O’Dell and another by the name of Stanley Levinson, who was a Jewish brother and an attorney who was an advisor to King. Both of them in the past had ties with the Communist Party USA. But both of them had claimed that they had left those ties alone and the FBI had no evidence that those ties still existed.

[00:28:38] And they had no, no evidence that King was involved in this, but the FBI continually to use this perspective that King was a communist that continued to use it as a way to burrow into his life. And to try their best to discredit him that he was not a minister, but they would say quote that he was at worst King was a communist and clerical garb.

[00:29:02] And at best King was what they said, quote, a useful idiot, meaning that he was simply being used by a communist. And so Hoover believed that and used that as a proof text to do horrendous things against King as a private citizen, including bugging him and following him everywhere he went. And then using that material, showing it to the politicians on Capitol Hill, showing it to national religious organizations to try to get them to back away from King and to not support the civil rights movement.

[00:29:35] Now, supposedly in 2027, the court seal on some of this information, the FBI gathered, supposedly gathered on King, will no longer be under court seal. The National Archives will be able to release this information to the public. The FBI claims they have evidence of Martin Luther King Jr. engaging in extramarital affairs.

[00:29:58] However, it seems to me that one engaging in extramarital affairs has never disqualified people for being involved in political life. Well, well, well. And it seems to me that if this information is true, then are we going to then discount George Washington? Are we going to then discount Thomas Jefferson?

[00:30:22] Are we going to discount the work and the labor? Of countless presidents of the United States. So I think we need to be clear that if this information comes out in 2027 and the FBI, what it says it has is true. That doesn’t take away from King’s sacrifice, doesn’t take away from his labors, doesn’t take away from the claims he made about America not living up to its creed.

[00:30:44] Now I’m not saying it makes it right, of course I’m not saying that. But I am saying that it should not lead us to think King is somehow disqualified. From being a leader in a, in a prominent spokesperson and a conversation partner for us today about how we confront some of our social inequalities.

[00:31:03] Alisha Searcy: Absolutely. Thank you for that. When Americans think about the civil rights era, they most often remember events in the American South. I live in Atlanta, so that’s certainly my context. But Dr. King said his 1966 Chicago campaign was among his worst experiences. And then nearly a decade later, violence erupted in Boston over busing. So can you talk more about how racial issues have differed in northern and southern cities?

[00:31:34] Lerone Martin: Yeah, but I think that this is part of the American myth right about, so the Southern exceptionalism, right? It’s those Southerners down there and everything else north of the Mason Dixon line was fine. And King knew that not to be true.

[00:31:48] As you mentioned, Chicago, Boston, and LA and New York, all of these places King knew about racism that was occurring there. The difference was that in the South, it was just more explicit because you had Jim Crow You had signs in the South that said blacks only, what would say colored only. You had segregation marked on buses and public transit.

[00:32:12] You didn’t have that in New York City. You didn’t have that in Boston, but you still had racial inequality, right? You had African Americans being redlined in certain areas of Boston. This is Dorchester and Harlem and New York City, right? And Watts and Compton in LA. You had in these cities, residential segregation.

[00:32:32] And when King tried his best to fight against those things, especially in Chicago and fighting for an open housing ordinance, to fight to say that it is illegal to discriminate in housing sales and housing transactions. He experienced tremendous opposition. The same people. And my dear, my dear colleague, Jean Theo Harris, is writing a book right now called King of the North, which will be released in the coming months, which examines this, and I’ve learned a great deal from Jean Theo Harris in this regard that Jean points out in the book that’s coming out soon that the same reporters These quote unquote reporters who were on the race beat for the New York Times and for the Chicago Tribune when King was marching and doing what he was doing in the South, they lauded him as an American icon.

[00:33:26] He’s a hero. But then when King turned his attention to the very racism in these people’s backyards in New York and Boston and in L. A. and Chicago, these same journalists started, started criticizing him. It was moving too fast. The New York Times said after 1965, after the Voting Rights Act, that that was enough, that King was doing too much when he was trying to attack economic inequality and housing discrimination.

[00:33:55] So I think that, you know, we need to be clear that racism has never been a Southern problem. It’s always been an American problem, at least when we’re talking about the U. S. that knows no bounds. It wasn’t just in the south, but it was certainly all over. And when King tried to attack it in the north, he experienced tremendous opposition.

[00:34:16] Alisha Searcy: So when history is taught in K 12 schools, Would you talk about whether or not you think the civil rights era gets sufficient attention when we compare it to other important historical eras? Are kids learning about key figures and events of the civil rights movement, Rosa Parks, the Freedom Rides?

[00:34:36] Birmingham, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, again, I live in Atlanta, so I think about people like Dr. Lowry and others. The March on Washington, Malcolm X, and Dr. King’s speeches, do you think kids are learning about these things in schools today?

[00:34:51] Lerone Martin: I think, ironically, I come from the perspective that I think it is being taught. However, I think what is not being taught is the opposition that these individuals face. I think that what’s being taught is this kind of American story of inevitable progress. And that look at Martin Luther King Jr. He was so brave and courageous. You too should be brave and courageous when you find yourself, you know, believing in something and you’re being opposed.

[00:35:20] But I don’t think what’s being taught is that it wasn’t inevitable that these gains that we’ve made and strides we’ve made towards being a democracy in this country. I don’t think that we point out the opposition. And I think that’s important because I think it would allow us to truly wrestle and deal with the burden of our history.

[00:35:44] It is not just the Ku Klux Klan. Who was opposing Martin Luther King jr. It was elected officials in Northern cities, as well as Southern cities. It was good middle class American citizens who organized in white citizens councils. We organized into Mississippi sovereign commissions. It was good white middle class folks in Chicago and some of the neighborhoods in Chicago, including Cicero and others, Gage Park, Marquette, all these areas in Chicago as well, who are opposed.

[00:36:21] And I think it can help us. To be honest about our history and maybe perhaps give us more perspective about the role we play today when people are calling for justice and equality and where we stand on the issue. I think if we are able to point out that the Southern Baptists, for example, many of them were opposed to the civil rights movement.

[00:36:43] Many of the folks who are part of the National Association of Evangelicals were opposed to Martin Luther King Jr. and the efforts he was making. Billy Graham was opposed to the efforts King was making, saying the King was moving too fast. I think if we’re honest about who opposed these things, then we can look at our history with honesty.

[00:37:02] We’ll be able to bear the weight of that history, and then we’ll actually be armed to help to create a better future. Because we won’t be telling our young adults and our students a lie, but we’ll be telling them the truth. And so they’ll have perspective on where they stand on modern day issues by being informed by the courage that it took, and also the way that some people made mistakes in opposing the civil rights movement. Maybe we can learn from those mistakes today.

[00:37:31] Alisha Searcy: I have never heard anybody talk about that in that way. Thank you for saying that and for sharing that is so true. It’s almost like we romanticize Dr. King and, you know, we have the celebration and we certainly need to honor his life, but we also have to talk about how difficult it was and what that really means if you take on this kind of work. So thank you for saying that.

[00:37:54] Lerone Martin: I appreciate the question and I just want to add a part to that and I think it’s important We’re seeing curriculum being written for elementary school students in large states such as Texas, which really have an influence on how curriculum and textbooks flows throughout the country.

[00:38:11] I’ve learned this from my colleagues in the school of education at Stanford. And I think that it’s important because we see if we don’t tell the story of who these people were, who are opposing these things. Then we can end up getting people saying, you know, well Martin Luther King Jr. is a perfect example of why anytime you see something that you don’t like, you should stand up for it.

[00:38:34] But no, like that King wasn’t just about standing up for individual rights. King wasn’t just for saying, oh, this person who wants to pray at a halftime of a football game, you know, stood up for their right to pray at a halftime of a football game. They’re just like Martin Luther King Jr. No, I think if we know the full context that King was trying to stand up for equal rights for everyone and was opposed by certain people because King was trying to include the marginalized and the oppressed.

[00:39:05] And then we get to see the opposition. I think it can give us a clear, clear eyed assessment of the civil rights movement. And then we can just be honest about where we stand today.

[00:39:18] Alisha Searcy: Ditto. I want to move to 1967, 1968, when Dr. King and SCLC launched the Poor People’s Campaign. And you’ve talked a lot about his economic work, which took him to Memphis in support of the striking sanitation workers. So can you talk about the message of the meaning of his last speech? I’ve been to the mountaintop and the days leading up to his assassination on April 4th,

[00:39:47] Lerone Martin: 1968. Yes. You know, and it’s a story in Memphis that we have to know that involves unfortunate tragedy, that it’s. About economic inequality, African American sanitation workers were, were not able because of the city and the mayor there were not able to join with a union, a union that’s known today as the American Federation of State, Municipal and County employees.

[00:40:11] They were not able to join that union. Therefore, the African American workers there did not have sick pay when it rained. They were sent home. They were not paid when they came back to work and worked overtime. They were not compensated. And because they were not allowed into the break room and the work room that two individuals in Memphis in February, two African American sanitation workers were literally crushed to death in a trash compactor because it was raining and they were taking shelter within the trash compactor and someone pressed the button and they died because they could not belong to the union.

[00:40:46] They had no rights. So they started a campaign. They walked off the job and protest over a thousand sanitation workers. They called him Martin Luther King Jr. as I mentioned earlier, because they thought he could bring attention and financial resources to their striking efforts. They had no union, people were not working, so they thought King could help bring in resources so people could have somewhat of a small allowance so they could provide for their families while they were on strike, trying to negotiate union rights.

[00:41:16] King comes into town, he speaks in March, and then he speaks again of course April 3rd, the night before he’s assassinated. And in this speech he offers, let us have a kind of dangerous unselfishness. And he uses the story of the Good Samaritan, uses the story to say that in the, in the Good Samaritan story, in the gospel that Jesus tells that there is a man who was walking, he is robbed on the road down to Jericho, several people, including a priest.

[00:41:47] And a Levite and others don’t stop to help the man because they’re afraid about what will happen to them. And King says, the good Samaritan reversed the question. He said, what will happen to this man if I don’t stop and help him? And King says, that’s the question before us today. What will happen to the sanitation workers if we don’t stop and make sure that they have recognition for collective bargaining so that they can have rights, that their work is important, their labor has dignity, and that their sanitation workers and their work is just as important as a physician.

[00:42:24] King says that if the sanitation workers don’t do their job, right, then the whole city will be overrun with trash and with the rats, and then the physician will be overwhelmed with people being sick. Right? So it was so important to make sure that these workers have their equal rights. And so King says at this speech, and he, and this is a famous part that many people know, and then he ends by saying, we’ve got some difficult days ahead.

[00:42:49] Right? And he doesn’t know what’s going to happen, but he says that I’m not worried anymore. I’m not afraid. You know, there were death threats that he received on his way to Memphis. There were death threats he received in Memphis, but he said he wasn’t worried because he had been to the mountaintop. He had looked over and he had seen the promised land and then he’s using the language of Moses, right?

[00:43:09] That people understand this from the Bible and people are moved by this sort of metaphor he’s using. And he says that he’s looked over and seen the promised land and he says, I may not get there with you, but we as a people will get to the promise land. And it’s a beautiful moving speech, especially for the fact that it’s given the night before he’s assassinated.

[00:43:29] But what’s so important about that speech is not just to be moved by King’s sacrifice. But the importance of the fact that he was there trying to help workers achieve economic equality.

[00:43:42] Alisha Searcy: The way you talk is almost poetic. So thank you. I got arrested for just a moment, caught up in all that you were saying, and again, just powerful words, just a powerful man who literally sacrificed his life for the vision, right? That he had, what he was trying to do for poor people and so many others. So my last question is how can policymakers, schools and parents draw on lessons from Dr. King and historical figures from the civil rights era to better understand race in America?

[00:44:16] Lerone Martin: My answer to that is make Martin Luther King Jr. your conversation partner. And to do that does not necessarily mean you’re going to agree with him all the time. But it is to always be in conversation with him. And part of the work that I do at the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University is to bring King’s words to life and to allow people to read them and converse with him and to engage with him and to say, as we confront certain issues today, you know, how did King confront similar issues in his life?

[00:44:55] And then now that I’m armed with that information, how can I then engage in the world accordingly? And I think that that’s the best way for policymakers, for students, for parents, for all citizens, is to not just on this holiday, although I’m thankful for this holiday, but for every day for Martin Luther King Jr. to be your conversation partner. At the King Institute, we partnered with Stanford Digital Education. And we offer a class to title one high school students. These are high schools that are at least 40 percent of the student body is on free or reduced lunch. We have hundreds of students who take a class with us on Martin Luther King Jr. And if they pass the course, they get Stanford course credit for it on their transcript to show that they can do college level work.

[00:45:45] The final assignment, the final assignment we ask these students after they’ve spent a semester of doing a college course with me remotely on Martin Luther King Jr. Is that we then ask them, okay, find a pressing social issue in your community and tell us, write a short paper.

[00:46:04] About how King can help you think through this problem and its solution. So we’ve had students write on things such as food deserts in their community. We’ve had students write on things such as poor education or not having the funds to have AP classes at their school. And we’ve also had students talk about popular culture.

[00:46:26] About how King is invoked in the music of Kendrick Lamar or Beyonce or others. And it’s a powerful class, but it allows students to be in conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr. And that for King to be a part of their toolkit as they live their lives and try to engage in moral and ethical reflection.

[00:46:46] And that’s the advice that I would commend your listeners to, is to make Martin Luther King, Jr. part of your moral and ethical toolkit. So that when you confront problems in your personal life and societal life, you can have a conversation with him. And perhaps. Given his commitment and all that he experienced, he can provide you with some perspective and insight. On how to move forward as we confront some challenging times today.

[00:47:12] Alisha Searcy: Well, I know we’re not in church, but amen.

[00:47:18] Lerone Martin: I was raised in church. I was raised in church and I am a Christian. And so I am very much so informed by the tradition that informed Martin Luther King Jr. And so I take your amen as the highest compliment.

[00:47:32] Alisha Searcy: Please receive it that way. Thank you so much for your time today and sharing with us and teaching us. Every year I hope we learn more and more about Dr. King and his legacy and thinking about what you’re doing with students. I don’t know if Dr. King would have ever imagined what his legacy was going to be. But I am sure that he would have loved to know that this is the kind of work that continues and the seeds are continuing to be planted in young people.

[00:48:01] Lerone Martin: Thank you so much. That means a great deal to me. I feel very privileged, but I feel a heavy responsibility to try my best as an educator to figure out how I can contribute.

[00:48:12] I mean, everybody can’t speak as eloquently as Martin Luther King Jr. Everybody can’t You know, contribute financially to the movement, but all of us in our own little circle of life, we can find a way to serve. And I’ll leave you with this. King often would say one of my favorite sayings of Kings. And he would say life’s most persistent and urgent question is what are you doing for others? And I try my best to implement that and see this high school course. That we offer for free for high school students as one way that I’m trying to do something for others and to pay it forward.

[00:48:52] Alisha Searcy: And indeed you are. Thank you so much. Keep up the great work.

[00:49:09] Albert Cheng: Well, fascinating interview indeed. Yeah, I really enjoyed that one too, Alisha.

[00:49:13] Alisha Searcy: It was great. And what a tremendous way to honor Dr King. It was a great opportunity to hear from him and to talk about Dr King and his legacy. So great way to celebrate the holiday.

[00:49:24] Albert Cheng: That’s right. Let’s move on to wrap up the show.

[00:49:26] The end is drawing near for this episode. Before we close it out, a tweet of the week. This one comes from Ed Week. It’s referencing an article from Allison Klein. The tweet is federal ed tech dollars are running out. What happens next? Check out the article. You know, Alicia, we’ve had guests, quite a few in past episodes, talk about ESSER funds and how schools are spending them.

[00:49:48] And this impending fiscal cliff, you know, as these dollars run out, what are schools going to do? This article. It’s talking about that issue, but with a specific focus being on funding technology. You know, software devices, that kind of thing. And so anyway, check it out. I think there’s another piece to the story about what school is going to do once these federal dollars run out.

[00:50:09] All right. And finally, just to tease the next episode, we’re going to do a special episode for Holocaust Remembrance Day. We’re going to have Alexandra pop off. who is an award winning literary biographer and the author of Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century. I think there’s going to be much to talk about and learn, so I hope to see you all for our next episode of the Learning Curve podcast next week.

[00:50:34] Till then, hey Alisha, thanks for being on, and for the rest of you, be well. Until then.

[00:50:40] Alisha Searcy: Hey, this is Alisha. Thank you for listening to the learning curve. If you’d like to support the podcast further, we invite you to donate at pioneerinstitute.org/donations.

In this special MLK Day episode of The Learning Curve, co-hosts Alisha Searcy and U-Arkansas Prof. Albert Cheng interview Prof. Lerone Martin, Martin Luther King, Jr. Centennial Professor at Stanford University and Director of the MLK Research and Education Institute. Dr. Martin offers deep insights into the life and legacy of Dr. King. He explores MLK’s role as a spiritual and political leader, advocating for nonviolent protest and “soul force.” Prof. Martin discusses the dynamic between Dr. King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and figures like Bob Moses and Fannie Lou Hamer. He highlights how MLK’s understanding of history, literature, poetry, and hymns influenced his iconic speeches, including the famous “I Have a Dream” address. Dr. Martin then delves into MLK’s struggles in Birmingham, the challenges he faced from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and his “Mountaintop” speech before his assassination. Prof. Martin also examines the Civil Rights Movement’s impact on both Southern and Northern cities and its place in contemporary education, urging policymakers, schools, and parents to learn from MLK’s teachings.

Stories of the Week: Alisha shared an article from the CBS News on the new Chicago Board of Education to be seated among financial crisis, Albert discussed a story from The Advocate about the rise and fall of IDEA charter schools in Louisiana.

Guest:

Lerone Martin is the Martin Luther King, Jr., Centennial Professor in Religious Studies, African & African American Studies, and The Nina C. Crocker Faculty Scholar. He also serves as the Director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. Prof. Martin is an award-winning author of The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism. His commentary and writing have been featured on The NBC Today Show, The History Channel, PBS, C-SPAN, and NPR, as well as in The New York Times, Boston Globe, CNN.com, and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He currently serves as an advisor on the upcoming PBS documentary series The History of Gospel Music & Preaching. He earned his B.A. from Anderson University, a M.Div. from Princeton Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. from Emory University.