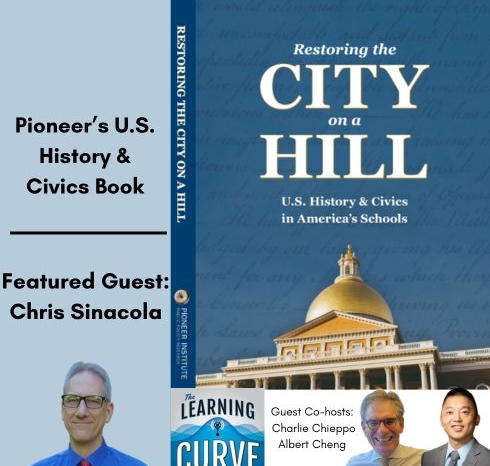

Pioneer’s U.S. History & Civics Book with Chris Sinacola

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, Podcast, US History /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve, Pioneer’s new civics book, transcript, October 25, 2023

[00:00:00] Charlie: Well, hello, everybody, and welcome to this week’s edition of The Learning Curve podcast. My name is Charlie Chieppo and I’m your co-host again this week. And once again this week, I’m glad to be joined by Professor Albert Cheng. We’ve been able to work, together in the past, and I’m looking forward to working with you today, Professor Cheng. So glad you’re here.

[00:00:41] Albert Cheng: Hey, good to be here again Charlie be back as a guest co-host I’m as Charlie said, a professor here at the University of Arkansas. I study education policy an emphasis on classical education. So good to be here and good to have these conversations you guys always feature here on The Learning Curve.

[00:00:57] Charlie: And if you run into Professor Cheng, you got to ask him [00:01:00] about pure math, because I never knew until I, until I met him. So, this week this week is interesting because my story that I have that I’d like to talk about this week actually jives with the topic that we’re going to cover today when we talked to Chris Sinacola about civics. We live in — to put it mildly — interesting times, right? We’ve got wars in the Middle East and Ukraine. Taiwan is threatened by China. And at the same time we’ve got no Speaker of the House. We’ve got a presidential election coming up.

[00:01:34] Charlie: And it’s hard to imagine a time when the American people need, more in need of the knowledge to make smart choices. So, Pioneer Institute, where I’m a senior fellow commissioned a poll and asked some questions, some of the same questions that immigrants have to answer in order to gain United States citizenship. And Massachusetts citizens scored a 63 on average in this poll. And I was really struck by that for a couple reasons, one in particular being that in some other work I’ve been doing lately, I discovered that Massachusetts is the only state in which the workforce, majority of the members of the state workforce have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

[00:02:17] Charlie: So, if we are in such a highly educated state and the scores are that bad, it really sort of makes me wonder about the state of civics in this country. Interestingly that the questions that people did the worst on were both questions about the United States Senate. In terms of knowing that there are 100 senators or that a Senate term is six years barely half of the respondents knew each of those things, which was pretty amazing to me.

[00:02:49] Charlie: To me, maybe the most troubling parts of the poll, though were breakdown based on respondents’ age and how many civic classes they had [00:03:00] taken. the group that did the best was those who were 65 and older, who got 75 percent of the questions right, followed by 55 to 64 year olds and 45 to 54 year olds. The three youngest categories 18 to 24, 25 to 34 and 35 to 44 all struggled to get just over 50 percent of the questions right, with 25 to 34 year olds doing the most poorly. So, it really speaks to our failure really to teaching civics. Now, the other thing that was interesting was that there is indeed a correlation between how many civics courses students have taken and how well they do. And obviously, judging from the scores, I think that it is pretty easy to arrive at the conclusion that we are not offering enough civics courses, or take enough civics courses.

[00:03:52] Charlie: This is one where I go back to the Founding Fathers, largely, I think, in this case, because I agree with them. [00:04:00] I tend to be much more of a the main purpose of education being to enable people to be practicing, contributing members of a democracy more than education is workforce development.

[00:04:12] Charlie: Certainly what the Founding Fathers wanted. And I think that clearly we have a long way to go to achieve their goal, and I think that the time in which we have spent kind of ignoring civics on the education front is one that really has to come to an end. So that’s, that’s what I wanted to talk about this week.

[00:04:31] Albert: That’s sobering news, I guess, about, you know, these polls that usually come up. It actually reminds me of a recent study I did with Jay Greene where we found education’s not even a guarantee, or the amount of education that you had wasn’t any guarantee of having civic virtue.

[00:04:45] Albert: And so, you know, there’s a National Affairs article we wrote about that about a year ago. But you know, I hope to learn a little bit more when Chris comes on here in the next segment to talk about the new volume where they, dig into civic education as well. My article maybe on, at first blush might not seem related to, civic education, but I couldn’t help but think about it as I read it. My article is about AI Charles Towers Clark is a contributor to Forbes, he wrote about his recent experience interacting with Conmingo. I don’t know if you know who that is or what that is.

Charlie: I hope you’re going to tell us!

Albert: Yeah, well, Conmingo and who or what, I don’t know what some words he used it because that’s the Khan academies AI bot tutors folks that log on to their system. So, Mr. Towers Clark here was talking about how he got some writing tutoring with Conmingo and described him as eccentric but whimsical and brimming with a sense of wonder.

[00:05:40] Albert: So, I don’t know. I wanna take a look at what sounds like his dating profile or well, yeah, I guess listeners, if you’re curious, go to Khan Academy. But, you know, in this article the question was raised of would teachers become obsolete now that we have this AI technology that, can essentially tutor kids on, on basic skills [00:06:00] and, it actually raised some interesting points thought and discussion, and I think the article does come out as properly skeptical. Actually, Sal Khan, who is the founder of Khan Academy himself doesn’t think AI is going to replace teaching and the human element of teaching.

[00:06:17] Albert: And in fact, in the article, it describes his framework of thinking about this, right. There are some things that are, Okay. you need a human to do. There are some things that humans can do with the help of machines. And then there are some things that machines alone can do without any human intervention. And it seems like Sal Khan of the camp that we’re not going to be replacing teaching. Certainly AI technology can enhance and augment what teachers can do. And so, you know, I think that comes close where I land on this. In fact, I think the line that really connects with our topic of today, civic education, is from the article — is the observation that there are certain things humans can do that AI can’t [00:07:00] and some of these things include judgment. And in my mind, I think about discernment, and I think you alluded to this a little bit when you’re describing your story, Charlie, that you know, civic education more than just knowing how government works, as important as that is, but you know, there’s an important element of being able to discern what good government looks like, what are the worthy ends that we as a society, as a society should pursue? You know, what’s good, what’s evil, what should we be critiquing, what should we be rejecting, what should we be embracing? And these are all questions of judgment, and those are things that don’t know that AI can teach us because it’s at its core a formative aspect.

[00:07:42] Albert: It’s a discernment aspect. So, I think AI might be able to deliver on technical skills, but, you know, some of these larger questions about what’s good, what’s evil, what’s worthy, I definitely think there’s something inherent in human nature that simply can’t be replicated or taught with these sorts of automated systems. So, I don’t know. I think there are people that might disagree with me there, but it seems to me. that’s where I land on this issue.

[00:08:08] Charlie: I think that’s so interesting because one of the things I’m struck by is that one of the real important pieces of American history to me is the fact that at key times in our history the American people have shown the wisdom to elect the right people. You have Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, FDR during The Depression and World War II, and I think that that is exactly right. I think that that’s what that comes down to. I mean, maybe I’m naive, but I don’t think that those things were just coincidence that we happen to have those people in place at those times with all that’s going on today. I kind of worry about our having the wisdom to make those kinds of choices. So, I think that’s, I am totally on board with what you’re saying there. Yeah, exactly.

[00:08:57] Albert: And not even to mention how, you know, we’ve just even seen in the past election cycles, how technology can be to certain ends that we might ought to reject so, yeah, it, it does come down to wisdom, as you say, and discernment.

[00:09:10] Charlie: Thank you, Professor Cheng. Coming up after the break, we have Pioneer’s Chris Sinacola talking about our new civics book that he’s co-edited.

[00:09:40] Charlie: Chris Sinacola is Director of Communications and Media Relations at Pioneer Institute. He has more than 35 years of experience in journalism, freelance writing, and was a reporter and editor at Worcester’s Telegram and Gazette from 1987 to 2015. Chris is the author of Images of America Sutton which came out in 2004 and Images of America Millbury, which came out in 2013. He has also served as editor of Pioneer Institute’s The Right for the Best Charter Public Schools in the Nation in 2018, and in 2021 A Vision of Hope, Catholic Schooling in Massachusetts and Hands-on Achievement, Massachusetts National Model Vocational-Technical Schools, last year. And now, just coming out Restoring the City on a Hill, U.S. History and Civics in America’s Schools. Sinacola holds a bachelor’s degree in Italian Studies from Wesleyan University. So welcome, Chris Sinacola.

[00:10:33] Chris: Thank you, Charlie. Glad to be here.

[00:10:35] Charlie: All right, Chris. Well, let’s jump right in. You’re co-editor of Pioneer’s new book, Restoring the City on a Hill, U. S. History and Civics in America’s Schools. Would you share with us a quick overview of the book, a few key chapters, and why its lessons matter so much for K-12 education and civic learning in this country?

[00:10:52] Chris: Sure, happy to do it, Charlie. Thanks for having me on. Sure. The new book, Restoring the City on a Hill, U.S. History and Civics in America’s Schools is a compilation of previously published white papers that Pioneer has done over the last several years, but it’s really more than that. By editing it and putting it together, we’re really telling a story. We’re trying to show a narrative of how U.S. history and civics instruction has declined in Massachusetts, in particular, and nationally, more generally, over the last several years, maybe five or ten years, you could say. And of course, Massachusetts was a model for civics education and education reform in general, beginning in 1993, and really has retreated from that position.

[00:11:37] Chris: That’s the view that’s laid out here in the book, and a lot of evidence is brought to bear on that point. So, we give some history. We give some examples of how various states, including Massachusetts, were successful in building curricula that mattered and that had a real impact and helped propel students to the front of the class, if you will, and then give a report card in Chapter 8 of some of the more popular and widely used civics curricula around the country and just give them a grade, as you would see, you know, when you, with great trepidation, would open your report card, at least in the days of yore. I don’t know what kids do today. Do they still do that? Or do they, do they get them electronically, perhaps?

Charlie: All electronic.

[00:12:18] Chris: All electronic, that’s what I, feared. And some of those like the 1619 project get a failing grade. Others like Hillsdale College’s curriculum get an A. And really, those grades are, they’re based, you know, of course, they’re somewhat subjective, I suppose, but they’re based upon our analysis of whether a curriculum Is going to do damage, if you will, to the traditional understanding of America.

[00:12:39] Chris: I mean, I think there’s a lot of room for interpretation and different points of view in history and debates are certainly welcome, but some of these curricula come at it from the point of view that America is a fundamentally racist country, that it’s hopeless, and that we have to undo everything and change everything.

[00:12:55] Chris: So, we try in the book to give folks some history and some reason to look forward and also some tips and recommendations on how a state that’s looking to improve their history and civics instruction might go about doing that in an inclusive way, drawing in lots of parents and teachers and all interested parties and have some real debate and put together something that would be a model of excellence really. So that’s sort of the short version overview of the book.

[00:13:22] Charlie: Yeah, I want to pick up on something that you said, which is, you know, you talked about how Massachusetts has generally been considered K-12 education leader, but, has not really distinguished itself when it comes to this topic. I want to get in, into some of the reasons why. I mean, it seems to me that, 30 years into education reform the state’s never implemented the law that required a U.S. history MCAS test as a graduation requirement. MCAS is the Massachusetts state test that you need to take in order to graduate from high school. Could you talk about U.S. history civics in the Bay State in particular what the book says about the decline in its history standards, as well as the civics lesson for young people about political leaders disobeying laws?

[00:14:03] Chris: Sure, you put your finger right on it, Charlie. The MCAS law, the education reform law, which gave birth to MCAS testing and higher standards, made clear that history and civics were to be tested as part of the MCAS system. Well, the state backed away from that in 2009 over the matter of a couple of million dollars, which, you know, it’s real money to you and me, but to budget, it’s really not very much money, right? And never implemented it. And 14 years later, we’re still waiting for that to happen. I don’t think it’s going to happen anytime soon, but it certainly hasn’t been for lack of folks like Pioneer Institute calling for it to happen.

[00:14:41] Chris: Because they’re really in a real sense that which is not tested is not taught, right? And there’s no question that you know, if you ask. your students, your, your kids, your grandkids, your nieces and nephews, do you get civics and history in school? Well, sure, they get something called civics, history, social studies — under whatever guise it is. The question is, how much in-depth is that? Does it rely on primary sources? Is it really comprehensive, and is it rather just driven by ideology, you know, whatever faddish ideas are out there at the moment? And I think too often the answer is B, it doesn’t really get into depth very much. Because after all, at the end of the day, teachers are looking at their classroom saying, ‘Well, I’ve got to teach the English and I’ve got to teach the math, for sure. And, you know, we have to have a science component there.’ So history gets kind of shunted to the side. And the result is what you have today, which is it gets less and less attention. And the state, you know, state education officials simply refuse to implement the law. So, you made an excellent point when you say, what lesson is that for young people? What message does it send? Well, it’s a very bad message. It’s that, we can pass a law and then everybody can ignore it. It’s really not the message you want to be sending to young people in America.

[00:15:55] Charlie: Yeah, especially not at a time when. People are already pretty dubious about government, I can see my [00:16:00] own kids just shaking their heads and saying, yeah, well, you know, par for the course or something like that to, that kind of thing. New York Times bestselling biographer, Paul Reed authored a foreword to the book, wherein he discusses the central importance of Winston Churchill’s working knowledge of history to inform his stellar World War II and Cold War statesmanship. Easy to forget that, you know, that’s what Winston Churchill made his living doing, which is basically writing about history. But as our country and world are in turmoil and political leadership seems lacking, would you discuss what Reid has to tell young people and the general public alike about studying history and civics to produce great leaders?

[00:16:38] Chris: I have to tell this story that — you mentioned in reading my bio that I went to Wesleyan — and in my freshman year, I had the I guess it was privilege of having a dorm room which overlooked the Olin Memorial Library, and I could see William Manchester himself, who was a professor at Wesleyan, at work on his magisterial biography of Winston Churchill. Some 40 years ago. And I looked down and asked a few people, I said, who is that old man there? You’re writing in the library every night with the light on. Well, it was, it was William Manchester. So, I had the books for years and years. And I probably should have gotten to them sooner than I did.

[00:17:18] Chris: But last year I said, ‘OK, self, it’s time to read this biography and see what it’s all about.’ So, I did make my way through the three volumes the first two of which Manchester wrote, and the third Paul Reed put together based on notes that he had provided to him. And they are magnificent is really the only word for it. Some years ago, I had read all of Churchill’s World War II six volumes which is an extraordinary piece of work as well. Of course, you correctly note that he made his living writing, in addition to saving Western Europe and some other work, you know, on the side. But, I mean, he won a Nobel Prize in Literature, for goodness sakes, and was, you know, the Prime Minister of England. So, he had a busy, busy career, and [00:18:00] also a prodigious appetite for… Just about everything in life. Exactly. But there’s no question when you read Churchill, I mean, I didn’t major in history, I always had a strong interest in history. But when you read Churchill, you just feel you’re in the hands of a master.

[00:18:15] Chris: You feel like you’re right there. And you take away so much, so many lessons. The warnings of what went on in Europe, leading up to World War Two with the Nazi takeover and, of course, the onset of the Holocaust, you really feel like you’re right there, you have a front seat on it, because his writing is so compelling, it’s so real, and the lessons, they’re just endless lessons that you can draw from Churchill’s work. And Reid did such a great job really finishing that biography. When I set out to get to the third volume and set out to read it, I thought, am I going to be disappointed, is this going to live up to the first two? is it going to have the same voice? And it absolutely does, it’s really a great, great piece of work. So, there’s a lot of lessons there, and in the book, we talk in the introduction that Paul Reid [00:19:00] wrote for the book, it basically focuses on Churchill and says, this is a man who knew history, he wrote history, tons and tons of history.

[00:19:08] Chris: I mean, when you look at the works he put out from his own experiences in South Africa and in Africa,further north, a book called the River War, My Early Life, I mean, his World Crisis on world war one, of course, the six volumes of world war two, which is, more than 4, 000 pages. It’s an incredible output. I mean anyone else would be happy to write, you know, one book never mind I don’t know you put out, but it was an awful lot of words and we’re very long and active life. So, you could do a lot worse I think then read Winston Churchill’s works in any history course. If you read nothing else, but Churchill, for example I think students might be better off than they are.

[00:19:50] Charlie: Well, that would simplify it. Simplify the policymaking, anyway. So, in the chapter, Shortchanging the Future, the co-authors talk about the wider national [00:20:00] crisis in K -2 history and civics instruction over the last three or four decades. Could you talk about that? Some of the reasons why U. S. history and civics lag far behind English, math, and science. I mean, touched on that a little bit in terms of what doesn’t get tested doesn’t get taught. But some of the other reasons in terms of being a priority in states and schools across the country.

[00:20:19] Chris:. Yeah. Well, I think that that first part of it is certainly some of it, and perhaps most of it, that you have a system that emphasizes testing the three R’s, reading, writing, and arithmetic. Teachers, naturally, being pressed for time, having lots of students, are going to focus much of their time on exactly that, and we’ve had long debates, in my household even, over MCAS and how it should be taught, how much it should be taught, and can certainly sympathize with teachers. Of course, in theory, I think the idea behind education reform was don’t teach to the test, right? You want to teach the kids what they need to know, and the test should come at the end of the year as a diagnostic or the middle of the year, whenever they administer it, just to tell, well, did they get the knowledge that they need? It’s not supposed to be an all-or-nothing, make or break kind of thing, the fact is, most students in Massachusetts do pass these tests, and of course, students who are in private schools or homeschooled or there are kinds of education where they may not even take the test, but they’re still getting a really good education.

[00:21:22] Chris: But it is a very important piece of as a diagnostic tool and for accountability. Now why has civics and history instruction fallen behind. Well, part of the reason is that we’re testing the others and not testing history. But I think there’s something else going on as well. And that is that science and computers and the internet and artificial intelligence are things which kids need to know. We live in a very scientifically literate age. And we need to have basic literacy and basic numeracy if they’re to survive and thrive and not fall hopelessly behind. When it comes to history and civics, there’s more, oh, I don’t know quite how to put it, but there’s more interpretation, I guess, would be the word.

[00:22:03] Chris: These debates are very fierce. I mean, I don’t know, Albert perhaps can talk to this a little bit later on, are there huge debates over the Pythagorean theorem or do people get very upset about how math is taught? I guess some of that happened years ago with the new math and the new new math and no one could understand exactly what they were trying to get at with that stuff. But certainly, anything that comes up, you know, when you talk about the origins of the Civil War, the American Civil War, you know, what were the main reasons behind it? And, of course, a lot of folks will say, well, it was about slavery and the extension of slavery to new states. And would it be all slave or all free? And others will say, no, no, it’s about states’ rights. And others will say, no, no, it’s a combination of this, that, and the other and industrialism and the cotton gin. And it goes on and on. So, I think in a sense, teachers might be a little shy from time to time delving into that.

[00:22:51] Chris: Everything is so contentious, you know, if you touch upon a history topic or a civil rights topic, you immediately get people with very strong feelings on both sides of the issue. And I mean, maybe some teachers just say, you know what, if we just teach them math, and we just teach them English, that’s great. And we’ll just cover these other bases as much as we need to, to check off the box and get their graduation requirements out of the way. But of course, if you’re not testing it, then there’s a real question at the end of the day, at the end of the school year, what exactly did they learn and what can they show that they learned? And unfortunately, in Massachusetts, where we’re not testing it, the answer is we don’t really know.

[00:23:28] Albert: Chris, think you’re really on the right track about the difference between teaching civics and history versus math. I mean, I’ve never heard of anyone arguing over the Pythagorean Theorem. I guess we mathematicians might debate over which proof is more elegant! But I think that’s a far cry from all the consternation we get when we start talking about history and civics education. I want to follow up and continue asking you to dig a little deeper in with teacher prep and state standards and classroom curricula.

[00:23:57] Albert: You know, for decades K-12 US history and [00:24:00] civics has struggled with poor academic quality in those aspects. You know, what are the book’s recommendations about using primary sources, for instance, like the founding documents, landmark U. S. Supreme Court decisions, civil rights era speeches. And you mentioned reading Winston Churchill, What are some recommendations to ignite teachers and students understanding of constitutionalism, self-government, and other important ideas?

[00:24:24] Chris: Sure. Well, in the report card, one of the factors that goes into getting a good grade, if you will, on your history and civics curriculum is having some emphasis, at least, on primary sources, original documents. And a parallel effort that Pioneer has this year and next is our American Citizenship Project, which is developing and promulgating a curriculum, which does in fact focus a great deal of attention on primary sources. So, everything from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, looking at things like Patrick Henry, Common Sense and on and Thomas Paine’s work and everyone else.

[00:25:02] Chris: You want to do that because there’s really no substitute for it. There are a tremendous number of really solid scholars, you know, who have made names for themselves throughout our history as scholars of the American founding and some of those names. the late great Bernard Bailyn, David Hackett Fisher, another one, of course, Shelby Foote’s Trilogy of the American Civil War, which is perhaps best described as the American Iliad, and it’s an extraordinary. And all of these are works which are as true as possible — they get you as close as possible — to the original sources because they’re built directly on them. There’s some interpretation, of course, that’s what historians do, but there’s no distortion, I think. They look at it wide eyed and really with a fair, open mind. And I’ve read quite a few of those authors and learned a great deal about them and really come to some startling realizations about the American Revolution, for example, as being more than just one revolution. It was really a series of revolutions in New England and then in the Middle Atlantic states and in the South. And the nature of the war changes, the nature of the conflict changes, and each area of the U.S. The different colonies had really different interests. When you look at it through that perspective, the lens of a really great historian, you come to a new understanding. It’s less likely, I think, if you’re looking at it through a textbook that has been kind of homogenized and pasteurized and distributed through a major publisher in order to satisfy everyone. There’s a real value in tackling those original sources and having students, of course, in a grade-appropriate way.

[00:26:38] Chris: You don’t want to drop the entire Federalist Papers on someone, I imagine. But selections from them. You know, certainly, and sometimes you may need to translate the language because what, you know, Hamilton and Madison and Jay were writing in 1788 doesn’t quite resonate with what a lot of young people, the way they speak today.

[00:26:57] Chris: And I mean, I have a copy, it sits on my bedside and I dip into The Federalist Papers from time to time. It’s a strange habit I have. And it’s tough going. I mean, some of that language is pretty dated and you have to read it again and you’re tired and you’re like, what exactly are they saying here?

[00:27:12] Chris: So, the role of a great teacher, of course, is to serve as a guide to that, but if you have those original sources near to hand and make them available to students, that really is a great way to get them inspired, rather than trying to, say, get through the book. We’ve all had that experience, right? Grade school or high school. And it’s like, Oh, we have to get through the book this year. We didn’t get to chapter 10 or we only got to chapter eight this year, we were somehow failures. But I think that’s the wrong way to look at it in a course like history or civics — or really any course, and I’m sure you’ve had this experience yourself — if you inspire your student, if that student gets it and suddenly their eyes light up and they say, wow, I get that, you know, they want to know more and they start learning on their own. Once you’ve ignited that spark in them, there’s no turning back. I mean, your job isn’t done exactly, but you can say that was a good day. So that’s one way to do it, you know, to focus on primary documents.

[00:28:07] Albert: You’re talking about excellence in curriculum, high-quality curriculum. So, one of the chapters in the book called Laboratories of Democracy profiles states that have developed high-quality state history and civic standards. So, moving from curriculum to standards. And, you know, that chapter as well profile states that have had good standards and allowed them — and others who maybe have allowed them to be degraded and politicized. So, in our current contentious political environment, what are some lessons about state history standards that policymakers and education leaders need to know?

[00:28:39] Chris: That’s a great question, because everything is so politicized these days, the American political dynamic is such that if it isn’t an election year, it’s the year before an election year, which somehow counts as an election year, or it’s six months after an election, and that counts as the honeymoon period for the — whoever is in power. You begin to wonder, well, when exactly is it that we could have the conversation about a reasonable, middle of the road, balanced, comprehensive set of standards? But yes, the book does talk about some success stories. And the good news, I guess, is that we cite New York, California, Indiana, South Carolina, Alabama, and Massachusetts, and you can look at that and say, Oh, red state, blue state, blue state, red state. That’s good. Because it proves one point, which is that your state doesn’t have to be all one thing or the other. It doesn’t really matter what the political leanings of the state happen to be. If a state has gone through a process that’s solid, that includes all parties, that is open to teachers and parents and experts and nonexperts, and everyone comes together in a way that doesn’t favor one special interest group over another, the result is likely to be stronger than if you just sourced it out to one group, one special interest group, and said, go for it, and they produce something and, it’s also, I think, a lesson for young people looking at this process, or teachers who may read the book, or policymakers — we hope they will read it as well — of course, having 50 states, 50 laboratories of democracy, if you will, allows America and education interests everywhere to try out new ideas.

[00:30:18] Chris: That’s the genius of the Founders, right? And if something is started in California and it proves to be a great idea, it spreads, that’s great. Other states can imitate it. On the other side of that, if you know, Florida or New York or Massachusetts try something that proves to be not so useful. Well, the damage is limited, if you will, to that one state or maybe one or two other states where it may have been imitated. So, you do have that ability to adjust the experiment in democracy and say, ‘OK, these models work. Let’s do more of them. These don’t.’ almost like an A/B test and in math and science.

[00:30:51] Chris: And one of the parts of that that I like to point to and have over the years, you know, both during my time as a journalist and afterwards in writing columns and so forth, is to focus on the Electoral College and I used to have enormous debates, of course, every time a candidate is elected with the most votes, you know, they don’t, quote, win the electoral college, which is really, or they don’t win the popular vote, rather. Of course, there’s no such thing as winning the popular vote, that’s not how we elect our presidents, but when that happens, folks immediately get upset, and they say, well, we shouldn’t have the Electoral College. I’d like to come back and say, well, do you want to be recounting every ballot in every precinct across the country?

[00:31:28] Chris: You know, there’s certain genius that went on with this. There were reasons that it was set up the way that it was in order to balance regional interests, the interests of large and small states, and to assure at least to some degree that candidates seeking to lead the country would be forced to campaign — not everywhere, that’s impossible — but at least in a variety of states, you know, rural and urban, west, east, north, and south. So, it’s just a great example of some of the things that you learn about as you study history more and more and should be part of a curriculum going forward.

[00:32:01] Albert: Yeah, I mean, you know, it sounds like an excellent chapter, and I was just perusing the table of contents and noticed that you’ve assembled quite a an excellent group of folks to basically make up this volume and so, you know, I want to bring in one of those folks, E.D. Hirsch core knowledge expert, and I think he’s probably familiar to a lot of the listeners here. So, he has a chapter titled “The Sacred Fire of Liberty,” and in it he discusses the vital importance of shared background knowledge as the basis for democratic education and for common civic purposes and actually even mentions a bit about how that why that’s important for bridging achievement gaps. Could you tell us a bit more about E. D. Hirsch’s chapter and what teachers need to better appreciate about why academic content and not simply just action civics is the best way to reestablish civics as the wellspring, so to speak, of our democracy.

[00:32:53] Chris: Yeah, I think one of first things you said in posing that question was pointed out that we had a lot of help with this book. I mean, [00:33:00] we have drawn upon the wisdom of a lot of very smart people in this book, right? Yeah. And it’s great to have those perspectives and that background it was a pleasure to edit it and put it together in one of the great, greatest reasons for that was that I got to read some words of really smart people who know a lot more about this sort of thing that I do, and E.D. Hirsch is certainly one of those people and I think because he’s been around a while, shall we say, he doesn’t take any prisoners, you know, he’s lived through a lot of this from, if you go back to A Nation at Risk, the 1983 report that sounded the alarm and his own books, Cultural Literacy, What Every American Needs to Know, he references Alan Bloom’s, Closing the American Mind.

[00:33:41] Chris: He touches a lot of the bases and the touchstones of the debate over the years, and one of the products of that kind of perspective is you come to some pretty strong conclusions. And one of those is that this is stuff you guys need to know, looking at young people and teachers and saying this trendy stuff, you know — look, there’s a place for, apps, there’s a place for video games, there’s a place for this sort of thing, videos and DVDs and all the rest along the way, but at the end of the day, you need to know some basic facts about history in order to have some, informed opinions and in order to be a good citizen of the United States, you need to know what happened. You don’t need to always agree about why it happened, but knowing who were the presidents and what century did the Civil War take place and why did we separate from England and what were some of the reasons for that? And what happened thereafter? And what was the War of 1812 about? it’s of course, endlessly rich in American history and what it has to offer young people. But if you don’t know the basics of it, or you have no idea what happened with World War I and World War II, who were the Progressives? Who was FDR? You know, why did he keep getting reelected and this sort of thing? It’s really difficult for young people to offer any kind of informed opinion about current events. You know, Charlie led off the program talking about the poll that Pioneer commissioned recently.

[00:35:01] Chris: And sure it was a small set of questions perhaps, but really woeful when you see the questions, they’re not that difficult. You know, these are things which new citizens of the U.S. have to know they have to get at least 60%. And many, I think do much better than that. They almost ace the thing because they’re very focused on becoming citizens. They still want to come to this country and become part of the great American Dream. And when you see how poorly some people perform on those, you have to wonder, how can they then go out to their town meeting? How can they go on the first Tuesday in November and cast a ballot with any assurance that they know what they’re talking about? We all want everyone to come out and vote, of course, but then when you see how uninformed some voters are, you’re like, hmm, what are we getting here?

[00:35:47] Chris: So, a bit disconcerted, shall we say? So anyway, Hirsch’s chapter really touches on a lot of those things talks about enduring truths through the ages, that content matters, that we recognize that look, there’s been some missteps along the way, you know, educators and educational establishment has spent years arguing about things like, what’s the best way to learn to read?

[00:36:08] Chris: And, you know, honestly, these debates are settled at some point, phonics works, you know, you look, say, this is the biggest picture, right? Looks/say doesn’t work as well. I understand that there are different ways of learning that different kinds of intelligence, a lot of nuance involved, but there are some basic truths that one can map out over time that aren’t difficult to grasp and that really ought to be applied. And it becomes for someone like Hirsch, I think, who’s seen a lot of this, it must be enormously frustrating, as well as to a lot of historians.

[00:36:36] Albert: Chris, I want to ask you one more question. And then afterwards, actually, if I could ask you to pick a passage from somewhere in that book you to read to our listeners. But have one more question. This last question for you and it comes from the last chapter, which is entitled learning for self-government. You alluded to this earlier. It’s provides a report card of various nationally recognized civics programs. For instance, we the people, iCivics, you mentioned Hillsdale and the 1619 Project. Could you dig into a little bit more about the greats? How some of the other programs did? Which programs did well, which ones did poorly? And explain a little bit more about why I know you touched upon this a little bit, but yeah, tell us a little bit more about this last chapter.

[00:37:20] Chris: We have a report card, which folks will find on page 148 of the book facing that chapter, Learning for Self-Government. And some of the winners, if you will, Hillsdale College’s 1776 curriculum gets an A-. The 1776 Unites curriculum gets an A. Florida’s K 12 Civics and Government Standards gets an A. The Jack Miller Center, A-, and Teaching American History from the Ashbrook Center gets an A. So those are the winners, if you will. There’s several with Bs, and then we go down to the bottom of the pile where we have Generation Citizen, which gets an F, and the 1619 Project, which gets an F.

[00:37:56] Chris: And, I hesitate to get too deep into it because it’s a subject —you look at what went into any curriculum and you have to be impressed, right? When you go to your local bookstore, whether it’s a chain or an independent, and you see how much work a historian puts into a book, even a book like The 1619 project, you’re like, wow, that’s a lot of information. And then you start reading it and you’re like, well, wait a second. You know, this doesn’t really add up. This doesn’t really jive with my understanding of what the American Founding was all about. And there does seem to be some bias here. So, it takes a lot of time to delve into these things and try to perceive what exactly is wrong with a given curriculum, because on the surface, they all look pretty good, in some ways, and they’re teaching kids stuff, right?

[00:38:41] Chris: Maybe not teaching them exactly what the vision that we want to share. But I think that if you look at the title of our book Restoring the City on a Hill and folks may, you know, look into that. There’s been a lot of talk over the years about what that phrase meant. Of course, it comes from, ultimately, from the Gospel of Matthew, but it was used in this [00:39:00] context by John Winthrop when he talked about, you know, Massachusetts would be a city on the hill.

[00:39:05] Chris: And it’s interesting, the original reference, of course, in the Gospel says that “You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden.” You think about the phrasing of that. It can’t be hidden. Well, here in Boston, we have Beacon Hill, and it’s pretty high up. And Massachusetts has taken this leadership position over the years. So, we’re kind of on the hill, and if we’re not doing well, well, those results can’t be hidden, right? I mean, they’re out there for the world to see. When you have declines in NAEP scores and you have declines in standardized testing and schools start throwing out the SAT and they don’t want to hear about it there’s probably a reason for that. Maybe they’re a little disappointed. It’s hard to hide that. because we are there as an example. So, what we’re trying to do with this book is say, let’s restore our position. I mean, I know there’s differences, you know, between the Puritan [00:40:00] outlook and ours today — and that’s probably a good thing. The Puritans came here and they established education at some point, but their idea of freedom of religion was freedom to believe as they did.

[00:40:11] Chris: You know, they weren’t happy if you were a Quaker or, you were a witch or something else. You weren’t welcome. Over time, of course, that understanding changed, and we now view that phrase and understand that position as speaking to American exceptionalism, speaking to the idea that the United States is, was, and remains a special place, a place where folks from all over the world want to come. And they want to come here and share in the American Dream and the opportunity that we have, precisely because we are grounded in certain values, and those values include education, and free thought, free expression, so as different as we may be from three and four hundred years ago, the folks who founded the country, we have a good thing going, and it’s Pioneer’s view, and the argument set forth in this book, that getting back to those classical liberal values, if you will, is very, very important, and that you don’t get there if you let special interests call the shots. And you don’t get there if you think, well, this country is fundamentally flawed, and we just have to scrap it all and start over. That’s not what we see from immigrants

[00:41:20] Albert: Chris, I want to give you the last word and give the opportunity to read a passage that you’d like to share with our listeners from this book.

[00:41:26] Chris: Sure. So, the concluding chapter, The Enduring Wisdom of the Founders, really tries to sum up the argument of the book and dispenses or sets aside all the stats and all the report cards and the grades and all that, and talks about the movement that we’ve seen. And this is something that certainly Learning Curve listeners have become very familiar with over the last several years — is the movement towards greater choice in education empowering parents. And we talk in this chapter about concluding really with a coalition of, for, and by the people. So, I’ll read a few of [00:42:00] these paragraphs on the last page of the book. And this is talking about parents, this coalition of Americans who don’t want to wait any longer for reform. They want to grab those opportunities for their kids.

“They recognize. that filling school curricula with material that pays homage to every special interest and identity group may soothe feelings but cannot bring us any closer to understanding the causes of our national greatness. They see that more than a million immigrants come to the U.S. every year eagerly and legally, drawn here not by any light or transient cause, but by a deep yearning for the liberty they can find nowhere else. They realize that the endless debates over education cannot obscure the fundamental truth that the American experiment in democracy continues to serve. As a model to the world, above all, they understand that ensuring the future success of that experiment requires cherishing our past and teaching our history to the rising generations.”

[00:42:56] Charlie: That’s great, Chris. Thank you so much.

[00:42:57] Chris: Thank you. It’s a pleasure.

[00:43:24] Charlie: Okay. Our tweet of the week this week comes from the fall, 2023 issue of Education Next. The great unbundling is the parents, rights movement, opening a new frontier in school choice. I think that’s one that I’m going to. Take a look at with interest. I have to say that this is one that Professor Cheng probably has a little more firsthand knowledge with because being that I live in Massachusetts and not in the United States um, we are sort of on the sidelines when it comes to anything having to do with school choice.

[00:43:53] Charlie: But I know that that certainly in Arkansas, Arkansas is on the, cutting edge of a lot of what’s happening in the school choice movement.

[00:43:59] Albert: [00:44:00] Yeah, that’s absolutely right. And well, ask me again in, three, four or five years, and I’ll tell you a little bit more about how this unbundling thing’s working.

[00:44:07] Charlie: Exactly. Exactly. Thank you, Professor Cheng. It was a pleasure to co-host with you again. Thanks for joining us. I appreciate it.

Albert: You’re very welcome. Glad to guest co-host with you again, too.

[00:44:17] Charlie: Great. And thank you, of course, to all of our listeners. Please join us again next week when the guest will be Leslie Klinger. He’s an attorney, writer, and the celebrated literary editor and annotator of the Sherlock Holmes stories Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. So, a perfect guest for Halloween. Thank you all, and we look forward to having you join us next week.[00:45:00]

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Charlie Chieppo and Prof. Albert Cheng interview Pioneer’s Chris Sinacola, co-editor of Restoring the City on a Hill: U.S. History & Civics in America’s Schools. Sinacola explores our new book, which addresses the state of history and civics education in K-12 schools in the United States. He shares the book’s insights about the decline in history standards, the importance of studying history and civics for leadership, the overall crisis in history and civics education, and the use of primary sources to enhance students’ understanding. Sinacola reviews how Pioneer’s book also profiles states with high-quality standards and evaluates various civics programs, emphasizing the significance of academic content in civic education. In closing, Sinacola reads a passage from the book.

Stories of the Week: Charlie addressed a poll conducted by Pioneer Institute which highlights a concerning lack of civic knowledge among citizens in Massachusetts, who had an average score of 63. Prof. Cheng delved into a story from Forbes exploring the experience of interacting with Khan Academy’s AI tutor “Khanmingo” and raised questions about the future of teaching with AI technology.

Guest:

Chris Sinacola is director of communications and media relations at Pioneer Institute. He as more than 35 years of experience in journalism and freelance writing and was a reporter and editor at Worcester’s Telegram & Gazette from 1987 until 2015. Chris is the author of Images of America: Sutton (2004) and Images of America: Millbury (2013). He has also served as editor of Pioneer Institute’s The Fight for the Best Charter Public Schools in the Nation (2018); A Vision of Hope: Catholic Schooling in Massachusetts (2021); Hands-On Achievement: Massachusetts’s National Model Vocational-Technical Schools (2022); and now Restoring the City on a Hill: U.S. History & Civics in America’s Schools (2023). Sinacola holds a bachelor’s degree in Italian Studies from Wesleyan University.

Tweet of the Week: