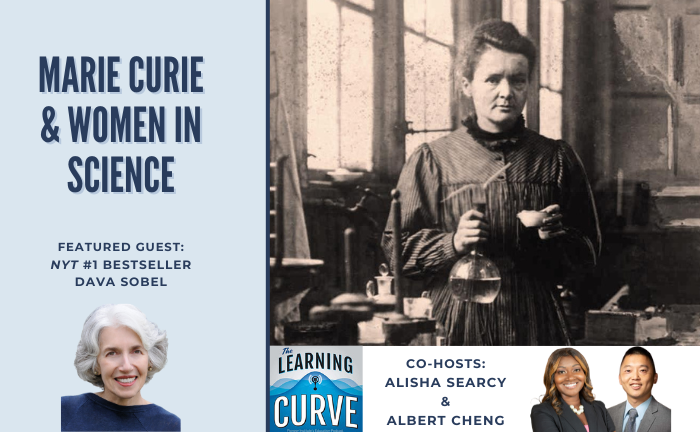

NYT #1 Bestseller Dava Sobel on Marie Curie & Women in Science

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Dava Sobel

[00:00:00] Alisha Searcy: Welcome back to the Learning Curve podcast. I’m your co host, Alisha Thomas Searcy, and joined by my other co host, Dr. Albert Cheng. Hey, Albert, how are you?

[00:00:33] Albert Cheng: Hey, Alisha, doing well. How was your Thanksgiving?

[00:00:36] Alisha Searcy: Nice and uneventful, but lots of good food and family and fun. How about for you?

[00:00:42] Albert Cheng: Good, good. Yeah, same kind of deal. We just had some friends over and had a Nice traditional Thanksgiving dinner.

[00:00:48] Alisha Searcy: Same. Feeling very grateful these days. Oh yeah. And celebrating the holiday season for sure. Yep, that’s right. So looking forward to a great show today, Albert. We’ve got Dava Sobel, who’s going to talk to us about Madam Curie in Women in Science. I’m excited about that.

[00:01:05] Albert Cheng: Oh yeah, me too. Uh, you know, I know a little bit about her life, but certainly looking forward to hearing a lot more.

[00:01:10] Alisha Searcy: Definitely always inspired by women and their greatness. So, but before we get to that, we’ve got some new stories to talk about. Yeah, that’s right. Why don’t you go first?

[00:01:21] Albert Cheng: Sure. I found an article with a provocative title. I mean, I don’t know if it’s clickbait or anything, but the premise was, was provocative, and I think there’s some validity to it. The title is from the New York Post. The title is, As a Teacher for 26 Years, I’ve Seen How We’ve Dumbed Down Education and How Kids Suffer.

[00:01:39] And this is an article that is drawing on another article that was Put up on the Acton Institute’s religion and liberty online platform. And then that author actually even drew upon Ted Joya, one of his sub stack articles. And, you know, I, I think the premise of these, we’ve, we’ve talked about this on the show quite a bit about how, you know, one of the issues we face in education is lowering expectations for students.

[00:02:01] They talk about this here and, and actually in the article and the content that’s been being discussed in these articles, you know, they add this observation that, you know, we also. don’t like to challenge students. We don’t like to give them challenging material. We lower standards for grading. We do things like prioritizing, giving them kind of fun projects to kind of distract them.

[00:02:22] And look, I’m not, I’m not against fun and learning. I think there’s a lot of place for fun and enjoying learning, but there’s a difference between. Simply amusing them in class with assignments that are there to distract them, you know, assignments that aren’t content rich. I mean, the world is an amazing place out there and, and there’s A lot of joy in, at least this is my view, you know, a lot of joy in figuring out and discovering what’s out there, and who am I, and who are we as people, and how do I fit in the story of humanity?

[00:02:54] You know, really all the great things of a liberal arts education, and a lot of that’s missing. So I think this is a provocative set of articles, really. That I want to just commend to our listeners to consider. I think there’s a lot to think through here and, you know, this is straight out of the mouth of a teacher who’s been around and observing this trend.

[00:03:13] Alisha Searcy: Yeah, it was a very interesting article. His tone is very strong.

[00:03:18] Albert Cheng: Yeah, that’s for sure.

[00:03:20] Alisha Searcy: He definitely has some very strong opinions, but I think you’re right. There’s something to be said about the way of education right now. And what’s being delivered, right? We talk about this all the time, as you alluded to.

[00:03:32] And that does concern me too, when I think about the fact that we may be dumbing down our education system. And I went to school a zillion years ago, but when I think about my high school experience in particular, I went to performing arts high school in Florida, but some of the classes that I remembered now, and that was again, a zillion years ago.

[00:03:53] were my AP American history course, my AP psychology courses, because of the discussion, the dialogue, the question, you know, that was made on me as, as we were having these really deep and important discussions about history, about psychology. And so those are the kinds of students that we want, right?

[00:04:12] Thinkers. Yeah. You can have good dialogue. You can. Agree and disagree. And so I think the big picture here. I agree with a lot of what this author was saying. So thank you for bringing that story. And it’s interesting. I think mine is pretty connected. It’s a story from education week, and it’s entitled the top 10 things that keep teachers up at night.

[00:04:37] Oh, huh? Yeah. What? So what keeps teachers up at night? A lot, right? You know, I’ll go through the list very quickly. Curriculum and standards is number ten. Nine is challenges with student achievement and learning. Eight, lack of parent engagement and support. Seven, ineffective or unsupportive school and district leadership.

[00:04:59] Six, school funding, resources and staffing. Five, political climate, state or federal politics. Surprise, surprise. Four. Teacher pay and financial concerns. Three, student apathy, engagement, and mental health, which I thought was interesting they put all of that together. Two, workload, preparation, stress, and lack of time.

[00:05:22] And one, student behavior and discipline. So none of these are shocking, but what really got my attention here in the timing, I happen to be talking to one of my mentees this week, and she’s newly in the classroom. She’s done other things in her career, but she’s, let’s call her a first year teacher. She’s in a low performing school.

[00:05:46] I’ll get this. She told me that at one time she has had nine people in her class observing her instruction. Well, people from the state from the district and her school and in her particular school, their area superintendent comes to their each of their classes twice a month. Think about that for a second.

[00:06:11] This is a pretty large district in metro Atlanta. And so I say that to say, when teachers are talking about the workload, the preparation, the stress as number 2 on their list, teachers have been talking about these things for a long time. I’m not sure we’re really listening. And so in my role at Democrats for Education Reform, this is something that I’m starting to talk a little bit more about that, you know, and I don’t want to get political, but I’ll just say that, you know, teachers unions have their job, but I would argue that there’s room for other organizations to really advocate for teachers in ways that they really feel listened to, because if we don’t have teachers, we are in a lot of trouble.

[00:06:52] And these are 10 things that, Many of them can be fixed, right, if we remove some of the politics in it, if we address teacher pay, if we address mental health, do something about their workload. I feel like we would have, you know, more people who want to go into the profession. To your point about your article before, if we return to a place where we’re not dumbing down education, I think our system would be more meaningful.

[00:07:17] both for educators and for students. This article was really important, and I’m glad that Education Week added this, and I think we got to listen.

[00:07:25] Albert Cheng: Yeah, yeah, and I think you make a great point, and really, you know, just to even connect the articles further, we talk about school choice a lot for families.

[00:07:33] You know, there’s also this aspect of school choice for teachers, that teachers that want to teach a certain way or have a particular style, you know, particular area of expertise. You know, like we can think of how, you know, teachers aren’t one size fits all either. Right? And so let’s put teachers in places where they love their jobs, love their colleagues, love the working conditions of the particular schools that they’re at.

[00:07:55] Alisha Searcy: Yes. Cheers to that. And I’m sure the teachers who are listening are happy to hear you say all of those things, right? Well, I hope so. Very good. Well, thanks for that. Up next, we have our guest, Dava Sobel, so stay tuned.

[00:08:08] Dava Sobel, a former New York Times science reporter, is the author of Longitude, Galileo’s Daughter, The Planets, A More Perfect Heaven, and The Sun Stood Still. The Glass Universe, and most recently, The Elements of Marie Curie, How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. She has also co authored six books, including Is Anyone Out There? with astronomer Frank Drake. Galileo’s daughter won the 1999 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Science and Technology, a 2000 Christopher Award. and was a finalist for the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in Biography, while the paperback edition enjoyed five consecutive weeks as a number one New York Times non fiction bestseller.

[00:09:08] Ms. Sobel is a longtime science contributor to Harvard Magazine, Audubon, Discover, Life, Omni, and The New Yorker. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the State University of New York at Binghamton. Ms. Sobel holds Honorary Doctorate of Letter degrees from the University of Bath, England, and Middlebury College, Vermont, and also Honorary Doctor of Science degrees from the University of Bern, Switzerland, and Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada.

[00:09:39] Ms. Sobel, welcome to the show. We are excited to have you, so we want to just jump right in. You are among our era’s most accomplished writers on the lives of scientists. While your recently published biography, The Elements of Marie Curie, How the Glow of the Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science, is receiving wide acclaim.

[00:10:01] Can you tell us what drew you to the scientific Joan of Arc? And give us a quick overview of Madame Curie’s life and explain why she remains the most iconic woman in the history of science.

[00:10:15] Dava Sobel: I am going to take a few steps backwards. I came to this book through the book I wrote previously, which was called The Glass Universe, and which is about a group of women astronomers at Harvard in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

[00:10:32] And all through my research for that book, I kept being surprised. By what the women had done, and I finally had to admit that I had come to them with embarrassingly low expectations and that even though I am a woman, somehow I had absorbed all of the negative attitudes toward women that were in the air when I was growing up in the 1950s.

[00:11:01] So I had to own up to my own misogyny. Wow. And it was really a pivotal moment for me and made me very desirous of telling other stories of women in science. And so the obvious iconic woman of science is Marie Curie, but I didn’t want to write about her because At the time, I didn’t have anything new to say, and I knew that there were a couple of biographies already in existence, but then I found out through reading a book called Women in Their Element that uh, um, Many other women had come to work in her laboratory, and it was her laboratory.

[00:11:50] So she, she started working with her husband, but he was killed in an accident when she was only 38. And. As a result of his death, she was made the director of this laboratory where they had worked together. And she was the only woman in the world in that sort of position. And she was also asked to take over the teaching of his physics course.

[00:12:19] And that made her the first woman ever to teach at the University of Paris, in several centuries of history there. So, She was world famous, partly because she had shared a Nobel Prize with her husband, but also now in her unique position. So, women all over the world who were interested in this new science of radioactivity, just flocked to her, really.

[00:12:50] If there was any way they could get themselves to Paris, she was like, likely to admit them to the lab if they were qualified. Wow. There were several parts to your question. I’m, I’m not sure I’ve, I’ve covered all of them. But very helpful.

[00:13:07] Alisha Searcy: I mean, we didn’t know that part of the story. That’s very helpful how she opened a lot of doors for other women.

[00:13:13] Dava Sobel: She certainly did. And it wasn’t that she sought out women to come work for her. She really, she just didn’t say no when they came to her. And that had a powerful effect. Many of these women went back to their home countries to become the first female professors there.

[00:13:37] Alisha Searcy: Excellent. So you mentioned a little bit about her life.

[00:13:42] I want to talk a little bit more about that. And so she was born Marie Sklodowska in Warsaw, Poland. And she was the youngest of five children whose parents were noted teachers, and she was taught in Poland’s roving clandestine flying university that enrolled 5000 women and evaded official czarist Russian control over Polish education.

[00:14:04] Can you talk about her youth and upbringing in the late 19th century, Poland, and how she became interested in math and science?

[00:14:12] Dava Sobel: Yes. So during her early years, Poland had actually fallen off the map of Europe. It was divided into three parts. And the part where she lived was controlled by Russia. And yet her parents were very staunchly Polish in their culture, their pride, in their heritage.

[00:14:36] And so, they were speaking Polish at home, and other languages too. They were both teachers, both her parents, and both believed that girls as well as boys deserved an education. Marie’s father was a physics teacher. So, he encouraged an interest in science in all his children. There was one boy and four girls.

[00:15:01] And the boy was able to attend university and medical school in Warsaw. But that path was not open to the girls because girls were barred from university education. So, for a while, Marie and Her sisters attended this secret university that was called the Flying or Floating University because the classes were held in secret.

[00:15:32] But as it grew, at first, the sessions were in people’s homes, but more and more women got involved. They needed bigger spaces, and there were various institutions that cooperated to have these meetings, although they were completely illegal. Very fascinating. Her parents were quite progressive for their time, weren’t they?

[00:15:55] Yes, they were. And unfortunately, Marie’s mother died of tuberculosis when Marie was only 10. And one of her sisters died of typhus at age 14. So she had a lot of grief in her life from an early age and many obstacles to overcome. But she had this wonderful attitude throughout her life. of not moping about when things didn’t go her way or when there was a serious problem to confront.

[00:16:31] And her manner of dealing with those things was just to figure out, Well, how can I get around this? Or what can I do to be helpful? And so she made a deal with one of her older sisters. So Marie. would work as a governess and earn money. And the older one would go to Paris, where women could attend university.

[00:16:56] There were none on the faculty, but they could be students there. And when the older sister got her degree and became a doctor, then it would be Marie’s turn. And that’s how she got herself to Paris. Wow, you

[00:17:11] Alisha Searcy: know, it’s interesting to hear about the many obstacles that she’s had to overcome in her life.

[00:17:18] Can you talk a little bit more, um, you mentioned that she worked as a governess in her young age until her family could raise enough money for her to enroll in school in Paris, as you mentioned, where she was one of 23 women to join the science faculty. And so we know that after graduating at the top of her class, she won a scholarship.

[00:17:37] So, can you talk also about some of the obstacles that she had to overcome in becoming the first woman in Europe to earn a doctorate in physics and the first female professor at Sorbonne?

[00:17:51] Dava Sobel: Going on to the graduate level required not only enough money to support yourself, but the approval of the faculty.

[00:18:03] And although she was Uh, foreign student in Paris for whom French was the second language, she managed to complete her first degree first in the exams and her second degree second in the exams and to be given a project to do outside of academia where she studied different types of steel for the French steel industry.

[00:18:34] And then she got an idea for a PhD level project, which was the start of all her great discoveries that led to her lasting fame. Her thesis was about her work with these new uranic rays, which she renamed radioactivity. And in the course of studying this strange radiation, the work got so interesting that her husband dropped what he was doing and joined her.

[00:19:09] And together, they discovered two new elements. And that’s what her doctorate was about her. Her dissertation was all about this work that had really led to a new scientific movement. And when she presented it, she was questioned by members of the faculty in front of an audience, but she defended her dissertation brilliantly and they congratulated her on being the first woman to earn the doctoral degree in physics.

[00:19:46] So she was the first woman, the first wife, the first mother, and at the time, although, of course, no one outside the family knew it. She was also pregnant. So the first person to defend the dissertation while pregnant.

[00:20:02] Alisha Searcy: Incredible. I want to go back for a moment. You mentioned her husband. We’d love to hear about their relationship.

[00:20:10] And in 1895, Marie married the French physicist Pierre Curie, and she shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in physics with him, as you mentioned, and with physicist Henri Becquerel for their groundbreaking work. And in 1906, P. R. Curie died in a Paris street accident. Can you discuss the lives, the partnership and marriage of the curies and how they were able to forge this mutual understanding and love not only to build a life and family, but also to work together to accomplish these remarkable pioneering scientific achievements?

[00:20:48] They really

[00:20:49] Dava Sobel: had a great time. the ideal marriage. So when Marie took up her job, the opportunity she had to study steel for the French industry, she was introduced to another physicist who had some experience that friends of hers thought might be useful. But they turned out, and this other physicist was Pierre Curie, who was eight years older than Marie, and they really liked each other, and it was a surprise to both of them because she had had a very surprised unhappy, disappointing, almost engagement to someone in Poland and felt very burned by the way that had gone.

[00:21:36] And Pierre had sworn off women because he thought women just would keep him from his science. So they were surprised at their attraction to each other and how well suited they seemed to be. And very quickly, they were talking about marriage and Marie resisted because her goal had been to get educated in Paris, but then to go back to Poland and really help lift up her fellow downtrodden Polish countrymen.

[00:22:13] So staying in Paris was never part of her plan, and yet it was clear that she would have opportunity in Paris to be a scientist, which would likely be denied her in Poland. So they did get married, and when she began her doctoral research, she was just working in a spare room in the school where Pierre taught physics.

[00:22:41] This was an industrial school. This was before he was teaching at the university. So it was just a very good advanced academy for very bright young men. And she had a room where she was choosing her field of study. So in 1895, x rays had been discovered. And the world was just on fire about x rays.

[00:23:06] Everybody was interested in them. In 1896, this other kind of radiation, which was originally called uranic rays, turned up. But people were so interested in x rays that nobody was pursuing the uranic rays. So she decided to study that. And very quickly she, she found, they were called uranic because they, they came from uranium or from any kind of ore that contained uranium.

[00:23:36] And she started looking for these rays in the other elements. And then her studies led her to believe that there were some undiscovered elements that also emitted. this new type of radiation. And that’s when Pierre decided to drop what he was doing and work with her. And together they discovered two new elements.

[00:24:02] One they named polonium for her native country and the other radium because It emitted so much of this radiation and this work is what led to their share of the 1903 Nobel Prize in physics, their studies of radioactivity, which again was her word. I do want to make the point that Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in any category in 1903 when she shared the physics prize.

[00:24:38] And then in 1911, she won the Nobel Prize in chemistry by herself. So she was the first. person to win a second Nobel Prize. And to this day, she is the only scientist ever to win both the physics and the chemistry Nobel. Wow,

[00:25:00] Alisha Searcy: that’s very important to note. Thank you for that. And it seems that even after he passed away, she continued to make additional scientific discoveries.

[00:25:11] Dava Sobel: She continued as a scientist for the rest of her life. And she was determined. To turn the very inadequate lab they had started out in into something really worthy of his memory. And she eventually succeeded in turning it into a world class research institution. Thank you for that. I’m going to turn it over to Albert.

[00:25:37] Albert Cheng: Let’s continue talking about Madame Curie’s work. I really like this quote. So I, you know, I have a math background. I love pure mathematics, and so I love to think about mathematics for its own sake rather than the application, so I was, uh, intrigued to hear Madame Curie say, you know, when radium was I was quoting, when radium was discovered No one knew that it would prove useful in hospitals.

[00:25:59] The work was one of pure science. And this is proof that scientific work must not be considered from the point of view of the direct usefulness of it. So, talk about that aspect of science, the theoretical and purely scientific quality of her work. And then of course, you know, get into the practical and really unseen lethal aspects of the, uh, sciences she pioneered.

[00:26:23] Dava Sobel: Yeah, so at the beginning it was pure science. It was a new phenomenon and she wanted to characterize it, see where it came from, quantify it, but one of the first things she noticed was that the material burned her hands and Pierre intentionally carried some, created a burn on his arm from the radium and published an article in the Scientific Nutrition literature about this burn and how long it took to heal.

[00:26:55] And medical doctors immediately saw this as a potential treatment for cancer. So this material that they fell upon through, through a Study of of a new atomic property was suddenly applied. And in fact, the one of the first ever treatments for breast cancer occurred in the Curies Laboratory. Huh. When a medical doctor brought two women into the lab and sure enough.

[00:27:25] Radium did destroy cancerous tumors and was used for, for decades as the cure for cancer. And that was another thing that led to her great fame, because since so many people were healed by these materials, she had a reputation as a great humanitarian. And you, you would think that the numbness and the pain in her hands.

[00:27:53] would have clued her in to the danger of the material. But when scientists are doing things that are really interesting, a few burns on the hands would not stop them. And that was certainly the case here. And it took a long time for people to admit how dangerous it was. And that really came about in the 1920s.

[00:28:19] And it came to light because of the dial painters, young women who were hired to use paint that actually contained radium to draw numbers on watches and instrument dials. Curious had never advocated putting radium in paint or any kind of commercial use of it. But nevertheless, it was used that way. And the women were instructed to bring the Paint brushes to a fine point by putting the brush between their lips, so they were adjusting the radium and it destroyed their jaws and killed them.

[00:29:02] Wow. And yeah, so when that came to light, it could no longer be denied. Wow. Wow. But it was still useful in cancer treatment and mostly what started to be used was not the radium, but the gaseous emanation from it, which we now know as the element radon.

[00:29:25] Albert Cheng: Wow. That’s a fascinating. Yeah. Thanks for, for including that bit there.

[00:29:28] That’s fascinating. Well, let’s get into just even talking about just even her wider impact. You’ve been talking about her role being, you know, a pioneer, really, for lots of other women in science. So in your book, you actually interwoven the profiles of many other women, her students, her collaborators, future colleagues, such as Frances Marguerite Perry.

[00:29:48] So she discovered the element Francium. Norway’s Ellen Gleditsch. And also, Madame Curie’s elder daughter, Irene, who won the, really followed in her mother’s footsteps, won the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. So, talk a bit more about Madame Curie as a friend, a mother, and a mentor to dozens of other women in science.

[00:30:09] Dava Sobel: Yes, well that was the part that made me want to write the book because nobody knew about the fact that 45 women passed through her laboratory. And also that during World War I, she trained 150 French women, and these were not scientists. These were ordinary citizens who were eager to help the war effort, trained them to be x ray technicians.

[00:30:35] Because there was such a demand and Marie herself and her daughter Iran, who was only 17 at the time, actually drove around near the battlefields in a specially equipped x ray van that she had created to x ray the wounded soldiers and help the medics extract bullets and, and shrapnel. So the women started to come in 1906, so the very year Pierre died, the first one came from Canada, and others came from Norway, from Eastern Europe, some of them from within France, and They all formed some kind of a bond with Madame Curie.

[00:31:22] Sometimes she was their direct teacher, sometimes she agreed to approach a project together and publish the results with them as a co author. As a mother, she, she was the perfect role model. As you said, her daughter followed her into the lab and also won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry and also had a very loving marriage with her lab partner.

[00:31:51] So the two of them worked together and shared that Nobel Prize in Chemistry. And Madame Curie had a lot of support when she was first trying to become a scientist from the men in her life because there were no women in place to give her that kind of help except for her older sister who is Who had made that bargain with her about helping each other get an education, but beginning with her father and brother who encouraged and supported her.

[00:32:23] And then Pierre, who completely respected her, joined her research because he admired it so much shared prizes with her. And because they had two children, really the only way she could continue working at first was because Pierre’s father, who was a widower, offered to move in and take care of the children.

[00:32:48] Even today, this is a major problem for women in science. Childcare. Something like 40 percent of women scientists in the United States drop out when they have a child. So she had this wonderful network and that enabled her. She was also a teacher. So she had taught for a while at a, a girl’s academy, a young women’s academy for French.

[00:33:16] young women who wanted to become teachers. She taught physics to that group. And then she even had a school for a while for her own daughter and other children, the daughter’s age in which she, Madame Curie, the Nobel prize winning scientist was the physics teacher and brought the kids into the lab and let them do hands on work in the laboratory.

[00:33:42] Albert Cheng: Fascinating. Just the level of impact she had. Let’s go back to, you know, you mentioned how she drove around x ray equipment around the front lines of World War I. Yeah, I mean, I’d like to hear a little bit more of that because, I mean, in addition to that, this was somewhat connected to her befriending of Albert Einstein and other luminaries of 20th century physics.

[00:34:01] She got support from two U. S. presidents, so tell us a little bit more about her life and work outside the lab.

[00:34:08] Dava Sobel: Yes, well, the First World War certainly drove her outside the lab. All the men. were mobilized into the armed forces, and she decided to do this x ray work. And for a while, she invited Ellen Gleditsch, who had gone back to Norway, to come and work in the, in the radium factory during the war.

[00:34:33] And Ellen did that, even though the travel from Norway to France at that time involved crossing some bodies of water that were, were patrolled by German U boats. The way she got to know Albert Einstein was through a series of very selective physics conferences that started in 1911. These were funded by a wealthy industrialist named Ernest Solvay.

[00:35:03] And he wanted to hear the top physicists in the world talk about the current problems and questions in physics. This was a very yeasty time. Radioactivity was helping people understand the structure of the atom. There was the realization that energy existed in quanta. This was something Albert Einstein was very interested in, the beginnings of his theories of relativity.

[00:35:33] So he was one of the people invited to this first elite physics meeting, and Madame Curie was another. And there were other very famous scientists there, Max Planck, Ernest Rutherford, Henri Poincaré. So those meetings took place just about every three years until the 1930s. Actually, they continue to this day, but for the rest of Madame Curie’s life, she was attending those meetings.

[00:36:05] And until 1933, she was the only woman in the room. She got to earn support from United States presidents because radium was such a boon, such a treasured cure for cancer. So an American reporter decided to raise money to help Madame Curie obtain more radium, which had become the most expensive substance in the world.

[00:36:35] And she raised a lot of money from American women, and then invited Madame Curie and her daughters to this country, where they were toured around and met college students, met scientists, and met the president. And on both visits, she was given her gram of radium by the president of the United States. So the first time it was Warren Harding, and the second time it was Herbert Hoover.

[00:37:07] Albert Cheng: Fascinating, again, just the level of her reach and her life and work outside the lab. So let’s get into a little bit about her outlook about science. And we alluded to this a little bit before. She talked about studying science for its own sake and thinking about its usefulness. But let me read another quote from your book.

[00:37:25] This is Madame Curie speaking. Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less. And so we live in this era, we continue to live in this era, of wide scientific discovery and innovation. So tell us about Madame Curie’s intellectual outlook and mode of inquiry towards scientific knowledge and technology.

[00:37:49] And then of course the flip side, as well as the cautionary lessons that we might draw about her work about the limits of science.

[00:37:55] Dava Sobel: Well, I think we still live today in an era of scientific discovery and innovation, but with decreasing faith in science and lots of misinformation on every hand, which can be very dangerous.

[00:38:11] And I like her attitude. I like let’s not waste time being fearful. Let’s try to figure it out. And the more we understand, the better chance we have for. doing something about the things that frighten us. People love to point to all the destructive things that science can do, but it isn’t so much the science, it’s the use to which the science is put.

[00:38:37] So radium, yes, it was very useful, but it also turned out to be terribly dangerous. For a while, they tried to contain it in lead boxes, but eventually It came to be considered toxic waste, and it went from being the most expensive material to the point where we have to pay to get rid of it.

[00:38:59] Albert Cheng: Well, so I want to make sure I give you the last word here.

[00:39:02] And then after this, invite you to read a paragraph or a passage from your book just to end our time together. And so, look, I mean, you know, really appreciate your time here. I mean, you’ve really described to us how Madame Curie revolutionized. The human understanding of physics and chemistry. She overcame many limitations that were common in her era.

[00:39:23] Limitations placed on women. So, yeah, give us your last word about her overall world changing accomplishments, her legacy, and the model she serves for women in science today.

[00:39:34] Dava Sobel: Well, maybe I can answer that question with the passage I read, but let me just say that in her lifetime, the periodic table of the elements, which we see now is an icon of science was really a work in progress and her work not only turned up two new elements, but one of the women she hired as a lab technician eventually also discovered an element.

[00:40:01] So her contribution to physics and chemistry was gigantic. And again, radioactivity helped scientists understand the structure of the atom. Certainly, women had fewer chances than men. That remains the case today. Things are better, but I think partly they’re better because of her and the many, many other women scientists.

[00:40:29] Marie Curie may be, well, let’s say she is the most famous woman in the history of science, but she was never the only one. And she never wanted to be the only one. So, I’m going to read a little bit now. One ending to Madame Curie’s story concerns the role she continues to play as iconic female scientist.

[00:40:54] By some lights, she sets a dauntingly high standard, as though success for a woman in science requires at least two major discoveries deserving of two Nobel Prizes. But she herself stood ever ready to explore physics with children, to train young ladies, how to teach science to girls, to make x ray technicians out of women with rudimentary schooling, and to open her laboratory to those who chose to join her in the pursuit of science as a way of life.

[00:41:33] In this spirit. She inspires followers to seek the happiness she found while pacing near the stove in the old shed, trying to figure out how nature works. Perfect.

[00:41:49] Albert Cheng: This is a fascinating interview. What a picture of Madame Curie you’ve got for us.

[00:41:53] Alisha Searcy: And thank you for inspiring us by doing this work.

[00:41:57] Dava Sobel: Oh, it’s been my pleasure entirely.

[00:41:59] Thank you.

[00:42:11] Alisha Searcy: Wow, Albert, that was such an inspiring interview.

[00:42:15] Albert Cheng: Yeah, that definitely was. You know, you just have these real feel good episodes every once in a while. And yeah, it’s amazing to just think about all the the people that came before us and we really get to follow in their footsteps.

[00:42:26] Alisha Searcy: Yes, and as a woman, I’m especially proud and excited to learn that history.

[00:42:31] So that was really good. Well, this week’s tweet of the week comes from the National Council on Teacher Quality and they have this teacher contract database. That talks about policy information over 145 school districts across the country. So you can look at contracts, salary schedules, all kinds of cool things.

[00:42:53] So make sure you check that out. I’ll be studying that to see how Georgia rates for sure and the other states that I serve in the South, but they do very good work. And so we’re looking forward to our show for next week. We’ve got. Dan Hamblin from the University of Oklahoma.

[00:43:11] Albert Cheng: That’s right. Yeah, looking forward to that show.

[00:43:13] He’s co author with me on a number of the papers we’ve written together. So looking forward to having him on the show to talk about the conferences that he’s been organizing on alternative educational models.

[00:43:24] Alisha Searcy: Awesome. It’s going to be great. Well, I will see you next week and look forward to seeing everybody else next week.

[00:43:29] See everyone else later. Hey, this is Alicia. Thank you for listening to the learning curve. If you’d like to support the podcast further, we invite you to donate at pioneerinstitute.org/donations.

This week on The Learning Curve, co-hosts Alisha Searcy of DFER and U-Arkansas Prof. Albert Cheng interview Dava Sobel, acclaimed author of The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. Sobel delves into the life of Marie Curie, the “scientific Joan of Arc,” exploring her extraordinary journey from clandestine education in Tsarist-controlled Poland to becoming the first woman to win two Nobel Prizes in different scientific disciplines. She highlights Madame Curie’s groundbreaking discoveries of radium and polonium, with her husband Pierre Curie, and her pioneering work in radioactivity. Sobel also examines Marie Curie’s role as a mentor to women scientists, her wartime contributions with mobile X-ray units, and her enduring legacy as a trailblazer for women in STEM. Through Madame Curie’s story, Ms. Sobel reflects on the power of scientific curiosity and its profound societal impact. In closing, Sobel reads a passage from her book, The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science.

Stories of the Week: Alisha analyzed an article from Ed Week on the ten things that keep teachers up at night, Albert discussed a story from The New York Post on the decline of education quality post the COVID-19 pandemic.

Guest:

Dava Sobel, a former New York Times science reporter, is the author of Longitude, Galileo’s Daughter, The Planets, A More Perfect Heaven, And the Sun Stood Still, The Glass Universe, and most recently, The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. She has also co-authored six books, including Is Anyone Out There? with astronomer Frank Drake. Galileo’s Daughter won the 1999 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for science and technology, a 2000 Christopher Award, and was a finalist for the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in biography, while the paperback edition enjoyed five consecutive weeks as the #1 New York Times nonfiction bestseller. Ms. Sobel is a longtime science contributor to Harvard Magazine, Audubon, Discover, Life, Omni, and The New Yorker. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the State University of New York at Binghamton. Ms. Sobel holds honorary Doctor of Letters degrees from the University of Bath, England, and Middlebury College, Vermont, and also honorary Doctor of Science degrees from the University of Bern, Switzerland, and Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada.

Dava Sobel, a former New York Times science reporter, is the author of Longitude, Galileo’s Daughter, The Planets, A More Perfect Heaven, And the Sun Stood Still, The Glass Universe, and most recently, The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. She has also co-authored six books, including Is Anyone Out There? with astronomer Frank Drake. Galileo’s Daughter won the 1999 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for science and technology, a 2000 Christopher Award, and was a finalist for the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in biography, while the paperback edition enjoyed five consecutive weeks as the #1 New York Times nonfiction bestseller. Ms. Sobel is a longtime science contributor to Harvard Magazine, Audubon, Discover, Life, Omni, and The New Yorker. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the State University of New York at Binghamton. Ms. Sobel holds honorary Doctor of Letters degrees from the University of Bath, England, and Middlebury College, Vermont, and also honorary Doctor of Science degrees from the University of Bern, Switzerland, and Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada.

Tweet of the Week: