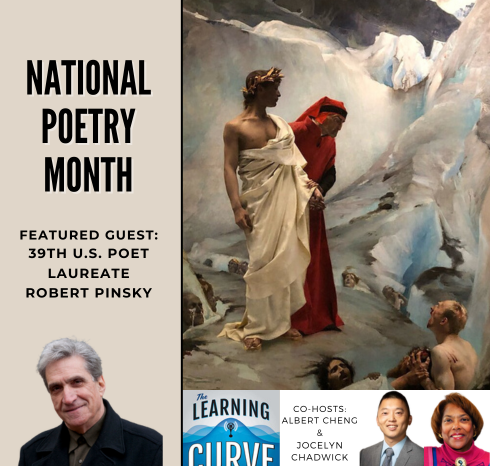

39th U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky for National Poetry Month

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

TheLearningCurve_RobertPinsky

Albert: [00:00:00] Well, hello, everybody. Hope you’re doing well today. Welcome to another episode of the Learning Curve podcast. I’m one of your co-hosts this week, Albert Cheng from the University of Arkansas. And this week, my co-host is Dr. Jocelyn Chadwick. Jocelyn, good to meet you, and great to have you on with me.

Jocelyn: It’s great to be with you, Albert. I am a college professor, high school English teacher before, and author. I work with teachers and students around the country, which I absolutely love, and glad to be here today.

Albert: yeah, I’m glad that you’re gonna be here with me for our guests coming up later Professor Robert Pinsky, former poet laureate actually as well.

So, I think we’re gonna have a lot of great discussions and conversations with him. And in case you didn’t know, April is National Poetry Month as well. So, I want to wish everyone a happy National Poetry Month and hope you spend some time engaging with excellent poetry. Well, before we get to [00:01:00] Professor Pinsky let’s talk some, some news.

And, I think you know, since we’re talking about poetry you wanted to share a poem as well to set the stage, so to speak. So, let me start with an article that was released in education next. It’s actually a study that Jonathan Plucker, Jennifer Madsen, and Paul DiPerna did.

It’s entitled, could our assumptions about who receives advanced education be wrong? And you know, I was fascinated by the study. I think they, took Data from some surveys that they did asking families about the kinds of ways they, get their kids to have, get advanced education.

So things like honors classes, formal GTE, GATE programs, and other means. And really the picture had some surprises. And so I want to direct readers to that, but you know, I want to bring this back to poetry really. You know, speaking of advanced education You know we have this, I guess, a conversation, a policy conversation these days of getting kids to have more access to, more rigorous learning opportunities and then that sort of thing.

But, you know, [00:02:00] one of the things that, struck me and I don’t know what your observation is, is that kids really aren’t covering poetry as much as we used to. I don’t know if I’m right about that. I think that’s my suspicion. And I’m reminded of uh, Really famous article by Dana Gioia, another poet laureate who talked about how poetry has kind of left our, not only just our schools, but the mainstream there’s like a 19, sometime in the 1990s, a really famous Atlantic article, but what’s your take?

Do you have any sense of this, Jocelyn, about just poetry instruction in our schools?

Jocelyn: Well, poetry is still a requirement. One of the great things about English language arts is that every student is required to take it from pre-k through 12th grade and poetry is in every part of the curriculum.

Now, the question becomes which poems are included, and which ones are deleted. And so, One of the favorite ones that I like, and it’s still, thank goodness, it’s still in the curricula, much of it depends on the districts and the states [00:03:00] and so forth, but because of today and, Professor Pinsky, I wanted to read Langston Hughes Harlem mainly because even though Hughes writes it during the Harlem Renaissance, the theme of the poem resonates so clearly today

Jocelyn: Our students as you mentioned earlier Albert some students feel that they’re not right for college some think they’re great for college But it’s all about dreams and aspirations.

And so here’s this point What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun or fester like a sore and then run? Does it stink like rotten meat or crust and sugar over like an apple? A syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode? And he puts, does it explode in italics and I just think, okay, that is so phenomenal because it’s an emotional [00:04:00] poem.

It’s a psychological poem. And as I said, my comment is that it’s more relevant today than it was. He wrote it, and that’s what great literature’s supposed to do.

Albert: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, and, great literature is, is memorable. I mean, I, remember this poem you know, coming across it for the first time in 11th grade we read it and actually we read the Play Raisin in the Sun as well alongside it.

And actually, I remember our English teacher also as part of that same unit integrated it with Death of a Salesman. And, you know, we talked about Just dreams deferred. And think it was an American lit class. So, so certainly talks about the American dream, and what that means.

And yeah, I think these poems and great literature, as you say they teach us a lot, you know, it’s not just about analyzing the poem, it’s actually learning from them, I think.

Jocelyn: Absolutely. That is absolutely correct.

Albert: Well, let’s not linger too much any longer and we’ll get to our, guest Dr. Robert Pinsky is on the other side of this break so stick around.[00:05:00]

Albert: Professor Robert Pinsky is the William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor at Boston University. From 1997 to 2000, he served as the 39th United States Poet Laureate and Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Pinsky is the author of numerous collections of poetry, including Proverbs of Limbo, Selected Poems, And The Figured Wheel, new and collected poems from 1966 to 1996, which received the 1997 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize and was a Pulitzer Prize nominee.

He is also the author of [00:06:00] several prose titles, including his memoir, Jersey Breaks, Becoming an American Poet, Singing School, Learning to Write and Read Poetry by Studying with the Masters, Democracy, Culture, and the Voice of Poetry. And The Sounds of Poetry, A Brief Guide, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Pinsky published the acclaimed translation, The Inferno of Dante, which was a Book of the Month Club Editor’s Choice and received both the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the Harold Morton Landon Translation Award. He earned his B. A. from Rutgers University and his Master’s and Ph.D. in Philosophy from Stanford University.

Robert, it’s a pleasure to have you on the show. Welcome.

Robert: Thanks for the invitation.

Albert: Well, so let’s start with your uh, before we get to poetry, your autobiographical prose work, Jersey Breaks, Becoming an American Poet. So this is a self-portrait that also offers a wider understanding of American [00:07:00] poetry and culture.

As we celebrate National Poetry Month, would you share with us your background and how you became interested in being a poet, and some of the formative literary and poetic influences on your life? What are some of those?

I grew up in Long Branch, New Jersey, which is a historic resort town. A great Winslow Homer here in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts near where I live is entitled Long Branch, New Jersey.

Homer also did many engravings of fashionable people walking on the Long Branch boardwalk. The town’s slogan, Was and is America’s first seashore resort. I like to say it’s where the American idea of celebrity was invented. The old obsolete idea of high society went to Newport, Rhode Island, or Saratoga Springs, New York.

Long Branch is where the famous [00:08:00] gamblers and show business people, actors, and patent medicine millionaires came to be on the ocean. My grandfather, Dave Pinsky, was a tough guy, immigrant, and part-time criminal who had a bar, the Long Branch Broadway, his bar, the Broadway Tavern was across the street from City Hall and the police station.

My father, his son, Milford Pinsky. Was an optician, which is a trade. It’s you don’t, it’s not a medical degree. My father was an optician in Long Branch and my other grandfather, my mother’s father, my mother was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. They moved around. But he, when I knew him, my other grandfather was a kind of a part-time window washer, Taylor Venetian, blind man, and so forth.

And the town people used to say of the town, the [00:09:00] town isn’t what it used to be. And that sometimes meant the days when presidents came there. It’s where Garfield, James Garfield died after he was shot. They took him there for the ocean breezes.

Albert: But when I was there, it was an ethnic resort town with the honky tonk boardwalk and swimming pools and a lot of Italian and Jewish and Irish immigrant families.

And I grew up, as I like to say among people who were not college educated, but they were extremely proficient joke tellers, gossipers, complainers, and liars. that’s fascinating. And I suppose all that formed you and are who you are today because of them.

Robert: There’s no question of that language was highly prized in my family and in the family of their friends and my friends were not readers of Virginia [00:10:00] Woolf or James Joyce, but they had in Long Branch High School, which was attended by both my parents, that’s where they met all my aunts and uncles and my many cousins, my brother and sister all went to Long Branch High and Miss Davis, the English teacher there made sure that people they’d read a Shakespeare sonnet or two.

Albert: Well, so, let’s get onto some poetry, and let’s start with maybe some of the oldest poetry.

Robert: Enough with Shakespeare, let’s get to some poetry.

Albert: Hey, well, so let’s start with the oldest or one of the oldest sets of poems, the Psalms. So these are sacred songs, sacred poems, you know, they’re meant to be sung and they’re widely used.

In religious ceremonies today, prayers, weddings, funerals, you name it. And so yeah, could you talk about the enduring influence of the Psalms and in particular what teachers and students today should learn from them you know, with respect to the ability of words and language to inspire us?[00:11:00]

The Psalms are just

Robert: one example of how much the 16th-century English translation of the Hebrew Bible has affected the speech, the novels, the stories, the jokes, the screenplays, the sitcoms, and all the uses of language in the Hebrew Bible. American English and I often think, not only of the Hebrew Bible, when people say, does anybody read poetry anymore?

One has to be delicate about this. I don’t want to blaspheme but inform the Holy Quran. is in a metrical form. It is part of what makes it easy to memorize compared to some other text. And so when somebody says, do people read poetry anymore? I feel like saying, have you heard of the Hebrew Bible? Have you heard of the Holy Quran?

in the case of the Psalms, And [00:12:00] the other books of the Hebrew Bible, and including the Gospels, the Christian Bible we know those through a 16th-century translation that there have been many modern revisions and amendations of, none has had that eloquence and the writing from Emily Dickinson to Mel Brooks.

Has been profoundly affected by that 16th-century eloquence. It’s all over the place. And it’s the power of language that is partway towards the song, sometimes all the way towards the song. I have never had anybody challenge me when I say, I don’t know of any culture In which that is not a powerful, important factor.

It’s easier to see in a culture like the Eastern European or an [00:13:00] Arabic culture. But in American culture, where our virtue is our ability to mix and mingle and hybrid, it’s not as obvious, but it is still quite powerful. I believe.

Albert: Well, speaking of culture and American life you’ve spoken about how the restoration of democratic culture is essential to American life and the intellectual health.

Of our civilization. talk about Poetry’s role in this, for instance, how’s poetry from say, Homer or Virgil, Dante, I know you have that translation. We mentioned Shakespeare Milton, you can add him to the mix. how has their poetry played a role in, culturally elevating and unifying Western civilization?

Robert: The immigrant Jews of a generation before me and a generation before that often named their male children, Herbert, Sidney, Milton, I think that [00:14:00] reflected the authority and prestige of the English language In its roots and its greatest accomplishments in a diluted form that came to me in the sense that I didn’t reflect on it this way, but as a reflect on it now, when I went to college after rather trouble than undistinguished high school career, I liked that the teachers did not call me Robert.

My teacher, Paul Fussell, addressed me as Mr. Pinsky, as I called him Mr. Fussell, and part of that social, let’s call it equality rather than democracy, or that generosity, included that if I was reading a poem by George Herbert or John Milton I was reading what [00:15:00] generations of the ruling class and of the newly educated classes in my country considered the best.

I think that in my parent’s generation, among their friends, they were mostly tradespeople that had little stores, a plumber, an oil burner, a man, a carpenter By the eighth grade, they had read a lot more. People today often get into high school, and though they didn’t quote a lot of poetry to one another, they spoke a kind of lively, I’ve already said inventive English language that I think had a lot to do with wanting the best.

You might want the best woolen garments. The best-corned beef sandwich, the best motorcycle, and the best language had to do with classic English [00:16:00] beginning with the King James Bible, but certainly including Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman and who knows all what. So these are not peripheral values.

Their central values. And it’s got to do with my patriotism. I’ve never had a strong group identity with any religion or ethnicity or certainly race, which is commercial, what I feel a kind of immediate recognition of that could be called patriotic is The idiomatic English that I have heard since I was a very small child.

The English I learned as a baby, and in which you and I now, Albert, are talking to one another.

Albert: Yeah. I’m absorbing all this in, [00:17:00] but so speaking of actually even some more wisdom here. So, in your book Democracy, Culture, and the Voice of Poetry just quote you here, poetry’s place in the United States is often presented, I think inaccurately as no place presents a note of anxieties about culture itself and about the idea of democracy.

unpack that for us, what do you mean by that? And, so what is poetry’s place and how did some of these 19th-century American poets really shape our forms of government today?

Robert: There are poets in African countries, in Asian countries, in South American Portuguese-speaking and Spanish-speaking countries, and all over the world, there are poets who, like their teachers and predecessors, were profoundly influenced by Walt Whitman.

As a place for poetry, I’ll suggest favoritepoem.org, [00:18:00], and the videos at favoritepoem. org, you will see no poets reading poems, and no professors lecturing or talking about poems. You will certainly not see actors reading poems. You will see. American readers, poems, mostly American, and you will see a construction worker have very cogent things to say about the Walt Whitman lines that he reads.

You’ll see the hockey hero of the American Miracle on Ice read a different Whitman poem and a Chinese filmmaker read the lines that he read in Mandarin that he gave to a girl he had a crush on when he was a teenager and that got him briefly into jail during the cultural revolution.

You will see a Cambodian American high school student in San [00:19:00] Jose read a poem by Langston Hughes. And how it makes her think about her family’s trial, and escaping the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia. So, again, if poetry is not important, Or Americans don’t read poetry.

are those people fake or invented? Is this part of artificial intelligence? No, they are real readers. So, I recommend, in response to the question, Albert, I do recommend favoritepoem.org.

Albert: yeah, I’ll be sure to check that out and hope others will as well. Well, one last question from me before I turned you over to Jocelyn and her questions. You just mentioned Langston Hughes and actually Jocelyn before um, you came on recited his poem Harlem.

And so, I think this is maybe our listeners might know that Langston Hughes did have some influence on Martin Luther King’s sermons and speeches. Certainly this one, I mean, [00:20:00] resonates with his talk on dreams and the future. So could you talk about just how a deep knowledge of, poetry hymns, spirituals, you know, how did these things inspire Martin Luther King in particular and his civil rights era leadership?

Robert: The American South was a surprisingly rich source, when people were invited to say a few sentences, to write a few sentences about a poem they loved, for that favorite poem project website, the Southern culture and the American culture. These, in particular, the Baptist churches, black and white, put a tremendous emphasis on music and on language, and American popular music American thought for good or ill American politics, have all been influenced by that culture, as [00:21:00] I understand it, compared to today.

The Presbyterians uh, the Episcopalians, the people who settled the South, lived far apart. You could not have one central place where people went to the church the authorities had set up. It was more reliant on very small, improvised prayers and on circuit riders. So that language and eloquence, what I’ve heard and read about the Southern culture music and eloquence were very important.

So I don’t really know a lot about this, but I would say it’s more that Langston Hughes. And Martin Luther King Jr. had shared roots, a very strong musical and poetical culture.

Jocelyn: I am so enjoying this, Robert. I mean, and being from the South, from Texas, you certainly honed [00:22:00] in on my background as a child growing up with all of this. So, in your book, The Sounds of Poetry, A Brief Guide, which I absolutely love. You wrote, quote, poetry is a vocal. This is to say, a bodily art, the medium of poetry is the human body, the column of air inside the chest, shaped into signifying sounds in the larynx and the mouth, unquote. Will you talk about how poetry is often best appreciated and most powerfully expressed when it is read aloud or performed?

Robert: I would say that the last word, or performed, gives me an opportunity to quibble. As at FavoritePoem. org, for me, when I write my poems, and when I read, I’m not concerned mainly with an expert performer. I perform my poems, sometimes with musicians. I have three [00:23:00] CDs where I do that. But performance, I’ll make the distinction, poetry is essentially a vocal art, for sure, not necessarily, but sometimes a performative art.

So the voice I am most interested in is in the title of the book Democracy The Culture and the Voice of Poetry voice. I am thinking of the voice of every reader, possibly not even reading aloud, but imagining what it would feel like to say all out of doors, look darkly in at him or further in summer than the birds pathetic from the grass, a minor nation celebrates its unobtrusive mass.

It’s each reader. Saying aloud or imagining saying aloud the words [00:24:00] of Dickinson or whoever. I’m very proud of the subtitle, Sounds of Poetry, a brief guide. I’ll use my brief example from that book of how physical art is. It’s a two-line 19th-century poem by a poet most people have never heard of.

This is a two-line poem. On love, on grief, on every human thing, time sprinkles Lethe’s water with his wing. when I say that poem, three times at the beginning, I physically, in my body, put my upper teeth onto my lower lip. On love, on grief, on every human thing, time sprinkles Lethe’s water with his wing. I don’t think [00:25:00] Walter Savage Lander was thinking about my upper teeth or anybody else’s or lower lip.

But he was an expert, and after many years of having read that poem, one day when I was reading it to myself, I noticed that, and it is confirmation for me that this is a bodily art, and This Walter Savage Lander, this upper class, very learned Englishman in the 19th century was orchestrating what my not very learned, not upper class, not English, not 19th-century body was doing.

On love, on grief, on every human thing. Moreover, in the second line, I end, as in the orchestration that Lander created without having to think about it, I purse my lips three times. Time [00:26:00] sprinkles Lethe’s water. With his wing, and that’s what I did is like analyzing music or analyzing the way somebody hits a tennis ball or shoots a basketball, it’s breaking down something that is done well to try to understand it, and it is, in all of these examples, bodily.

Jocelyn: I’m familiar with the poem, but I love your brilliant reading of the excerpt. that is just a joy. this is a really, I’m having a great day here.

Robert: Thank you, Jocelyn.

Jocelyn: let’s move on to something else. Well, another favorite guy of mine, is Plato. Plato wrote, quote, musical training is a more potent instrument than any other because rhythm and harmony find their way into the air.

inward places of the soul, on which they mightily fasten, imparting grace, and making the soul of him who is rightly educated, grateful. [00:27:00] Unquote. So Robert, will you share a few thoughts about what 21st-century Educators can learn from Plato’s ancient wisdom regarding the power of poetry?

Robert: There was a time when we thought it was very funny to learn by rote, and we laughed at sometimes in Asian countries, the children all saying something together in unison and memorizing, and for me, it’s related to another bodily practice that’s being revived cursive writing.

It turns out the physical act of writing cursively by slowing us down, can make information penetrate more deeply or more effectively. And when the favorite poem, Project was more active. I often heard about children, but also people who are suffering from dementia or terrible stroke. And to the family’s amazement, [00:28:00] the person somehow as a child had memorized a lot of, Oh, say it was Longfellow and now could recite as is true with speech defects stammerers and do not stammer when they sing or when they recite poetry. Possibly there’s a lesson in that. In my mind, it’s similar to the lesson that phonetic learning to read is quite effective. And again, may last longer because it is bodily Plato is right. I would just quibble pedantically as I quibbled with the word performative.

I think in the quotation, I don’t know what the Greek is it’s harmony and cadence. I would add melody. I think it’s a neglected aspect of poetry is that every sentence has a melody. We tend to [00:29:00] talk a lot about rhythm in poetry and clearly harmony has to do with like sounds, like rhyme or assonance.

But every sentence has a melody, Robert Frost’s letters about sentence sounds are very good at this. Emily Dickinson demonstrates it all the time in the poem that I quoted before Further in Summer than the Birds. Yeah, there’s harmony between the vowel and further in birds, but yada da da da da da da.

Pathetic from the grass, ya da da da da. A minor nation celebrates yada da da da da. So there is melody, harmony, and rhythm in music. It is also in language.

particularly in the degree of intensity in language that we call poetry.

Jocelyn: As you were [00:30:00] talking, I was thinking about Robert Frost, and then you said Robert Frost. So, wow. I don’t know any other accolades to keep saying, so I’ll just keep moving with the questions. I’m just enjoying hearing your thoughts.

.

Jocelyn: In addition to being a world-renowned poet, you’ve also won awards and wide acclaim as the first translator of Dante Alighieri’s masterpiece, Inferno. Will you discuss translating Dante into English and some elements of Inferno, which you hope modern readers will draw from your translation?

Robert: I’ll return to the idea of idiom and how When I hear a person speak, if I recognize the idiom, it’s not only American, all the stronger, if it’s Northeastern, if it’s New Jersey, I feel at home with that person, even if the person is saying something I disagree with violently, or saying something awful, I [00:31:00] also know This is part of my world.

I recognize this person culturally and it’s in many ways much stronger than the more obvious aspects of physical appearance, age, color, ethnicity, all of that. The language is very powerful to me and the Inferno of Dante comes, as I understand it, very much from his experience of exile.

Thank you. He was an exile and the home city in Italy of his time it was like a family, a nation. It was extremely important. He was unjustly accused of political wrongdoing in a post he held and he spent his life and wrote. His celebrated account of [00:32:00] hell, purgatory, and heaven in exile, and when, after it became an extremely well-known work the people running Florence at the time invited him back, all he had to do was apologize for having done something wrong.

He hadn’t done anything wrong. So, painfully, He said, no, I want deeply to be back at my birthplace, my home city, but I will not lie in order to get there. So he declined that and the fact that this is an epic scale work and a mental work that embraces everything in the world and he wrote it in Italian.

And in an Italian that often comments on the regional languages of people, memorably, one of the damned souls that converses with Dante says, I can tell from the way you talk I can, I think you’re a [00:33:00] Florentine like me. And indeed that is the case. So the importance of language, not as expressing, but as a central part of one’s communal identity and personal identity, is powerfully implicit in the Inferno.

He didn’t write it in Latin. He wrote it in what was still being invented, which is the idiomatic, normal language of his time and place and his native city.

Jocelyn: Brilliant. Finally, Dante’s Inferno is among the greatest poems ever written. Absolutely. It describes the journey of a fictional version of Dante through hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil.

Will you share with us what teachers and students in the 21st century can learn from [00:34:00] this timelessly classic poem that will help them live more fulfilling lives?

Robert: The theme of the Inferno. In my way of understanding it, is the most common failure of spirit on college campuses in the United States.

the absence or lack of self-wounding, and that was the Thomistic definition of sin for Dante. In that Catholic tradition, sin is an absence. It’s a negative evil is a failure of being, so that each person’s sin is as though you’re ripping a hole in yourself. You’re making your soulless.

And Dante’s sin that he is most preoccupied with, in himself, implicitly, is sin. Is the one that prevails most amongst undergraduates Dante, the English word for it in [00:35:00] 15th, 14th, 16th centuries was one hope, failure of faith, in our modern jargon, we call it a failure of faith. Depression. I consider Inferno by Dante the greatest work ever written about depression.

Jocelyn: That I, okay. I don’t have words anymore, Robert, to tell you how much this is really helping me with the work that I have loved for so long. And I, I think that you’re saying depression gives me an entirely different perspective, which means I’ve got to go back and reread Inferno for the umpteenth time, which I intend to do.

Robert: He says in the second canto, which is really the first canto of Inferno because the first canto is a preface to all three books, making a hundred, he says, I have the sin of fear.

Jocelyn: Yeah,

Robert: He resolves to go on a journey through hell, purgatory, and heaven. And then at the beginning of the very next canto, [00:36:00] having made that promise and commitment, he says, I don’t know if I can do it.

I don’t have confidence. He despairs. He gets cold feet, and I recognize that, and I believe many others recognize it. As well, he presents the writing of this large ambitious poem as a commitment in the opposite direction of depression and despair, and dealing with despair is the most vicious of all crimes because it keeps you from thinking you can be saved.

You can do anything better, right? I should add that I am not a learned translator. If the virtues in my translation of Inferno have to do with what I’ve said about idiom, and it’s physical, it’s not a feat of linguistic ability. It’s a metrical feat. It has to do with the sounds and creating a plausible, American idiom that doesn’t go out [00:37:00] of its way to be contemporary, but that is credibly somewhere between Dante’s Italian and the way I speak to people every day.

It’s physical, it’s as though I’m a horse, is what I did in translating in creating an English version of Inferno. It was not a feat of understanding the Italian language for Dante. I was like being a horse. Let’s leave it at that.

Jocelyn: Okay, let’s leave it at that. Your award-winning book, Figured Wheel, New and Collected Poems 1966 1996 includes poems like Avenue, The City Elegies That Portray Urban Safety and Pain, and the title poem, The Figured Wheel. and history of my heart express images of shopping malls, prisons, the environment, and human desire. Do you want to talk about the significance of a few key poems from this [00:38:00] collection?

Robert: Well, I, probably because I’ve opened it before to a poem of mine that people have noticed before. maybe it’s an appropriate finish. And, it has got a lot to do with commerce. Not only with shopping, also manufacturing, in the wonderful, uh, public television series, Poetry in America, there’s an episode of that series devoted to this poem, my poem, Shirt, in which, workers in the garment factory, and a famous, shoe designer. talk about the poem in ways that please me a lot. So do we have time for me to read it maybe as our finish?

Jocelyn: We would love to hear you read an excerpt from Shirt.

Robert: Shirt. The back, the yoke, The yardage, lapped seams, the nearly invisible stitches along the collar turned [00:39:00] in a sweatshop by Koreans or Malaysians, gossiping over tea and noodles on their break, or talking money or politics, while one fitted this armpiece with its over seam to the band of the cuff, eye button at my wrist, the presser.

The cutter, the ringer, the mangle, the needle, the union, the treadle, the bobbin, the code, the infamous blaze at the Triangle Factory in 1911, 146 died in the flames on the ninth floor. No hydrants, no fire escapes. The witness in a building across the street watched how a young man helped a girl to step to the windowsill, then held her out away from the masonry wall and let her drop, and then another, as if he were helping them up to enter a streetcar, [00:40:00] and not eternity.

A third, before he dropped her, put her arms around his neck and kissed him. Then he held her into space and dropped her. Almost at once, he stepped to the sill himself. His jacket flared and fluttered up from his shirt as he came down, air filling up the legs of his gray trousers. Like heart cranes fluttering.

Shrill shirt, ballooning, wonderful. How the pattern matches perfectly across the placket and over the twin bar-tacked corners of both pockets like a strict rhyme or a major chord. Prince, Prince. Plads, checks, houndstooth, tattersall, madras, the clan tartans invented by mill owners inspired by the hoax of Oshun to control their savage Scottish workers, tamed by a [00:41:00] fabricated heraldry.

McGregor, Bailey, McMartin, the kilt devised for workers to wear among the dusty clattering looms. Weavers, carters, spinners, the loader, the docker, the navvy, the planter, the picker, the sorter sweating at her machine in a litter of cotton as slaves in calico head rags sweated in fields. George Herbert, your descendant is a black lady in South Carolina.

Her name is Irma, and she inspected my shirt. Its color, and fit, and feel, and its clean smell have satisfied Both her and me, we have called its cost and quality down to the buttons of simulated bone. The buttonholes, the sizing, the facing, the characters printed [00:42:00] in black on the neckband and tail. The shape.

The label, the labor, the color, the shade, the shirt.

We’re just having that you know, you just have to sit in the silence to receive that at the, at the end of that. So thanks for that wonderful reading of your poem and, and for spending your time with us today.

Robert: I’ve had a good time. Thank you.

Thank you very much, Jocelyn.

Jocelyn: It’s been wonderful. Thank you so much, Robert.

Albert: I really enjoyed that interview as well. Well, that’s going to take us to the end of our show this week. But before we sign off first there’s the tweet of the week, which comes from Liz Willen from the Hechinger report. The tweet simply says interesting findings on teacher shortages and incentives to keep them.

and I’ll refer folks to that article. I think it’s a fascinating summary. About what some districts and states are doing with financial incentives you know, teacher compensation packages to, try to attract teachers to their schools. whether it be high-needs areas or areas where there are shortages.

So, anyway, I will refer readers to that. think this is a nice summary piece of some of the latest research on this topic. So check that out on our website for next week. Stick with us because we’re going to have Dr. Ashley Berner from Johns Hopkins University talk about her new book on educational pluralism.

And finally, before we sign off, Jocelyn, it was great to co [00:44:00] host with you. Glad to run the show with you this week.

Jocelyn: I always enjoy helping Pioneer Institute. So it was, and it’s always an honor.

Albert: All right. And of course, thanks for your reading again Langston Hughes, and for everyone else again, happy National Poetry Month pick up a poem or two in the next couple of days and see what you might learn from it.

Enjoy. See you next time.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts University of Arkansas Prof. Albert Cheng and Dr. Jocelyn Chadwick interview renowned poet and Boston University professor, Robert Pinsky. He discusses his memoir Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet; the enduring influence of sacred texts like the Psalms; and the wide cultural significance of classic poets like Homer and Shakespeare. Through his book Democracy, Culture and the Voice of Poetry, he shares his views on the vital role of poetry in shaping a vibrant American democracy. Pinsky also talks about the power of poetry in inspiring social change, the importance of reading poetry aloud, and the timeless wisdom embedded in classic poetry, like his translation of Dante’s Inferno. In closing, Pinsky reads his poem “Shirt.”

Stories of the Week: Albert addressed an article from Education Next questioning the conventional wisdom around advanced education; Jocelyn recited the poem “Harlem” in celebration of National Poetry Month.

Guest:

Robert Pinsky is the William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor at Boston University. From 1997 to 2000, he served as the thirty-ninth United States Poet Laureate and Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Pinsky is the author of numerous collections of poetry, including Proverbs of Limbo; Selected Poems; and The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems 1966–1996, which received the 1997 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize and was a Pulitzer Prize nominee. He is also the author of several prose titles, including his memoir Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet; Singing School: Learning to Write (and Read) Poetry by Studying with the Masters; Democracy, Culture, and the Voice of Poetry; and The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Pinsky published the acclaimed translation The Inferno of Dante, which was a Book-of-the-Month-Club Editor’s Choice, and received both the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the Harold Morton Landon Translation Award. He earned his B.A. from Rutgers University and his M.A. and Ph.D. in philosophy from Stanford University.

Tweet of the Week: