MassAnalysis: In search of a strong financial footing

You don’t have to be a member of the Finance Committee to know how fiscally responsible your town officials behave. With the MassAnalysis tool, created by the Pioneer Institute, residents as well as policymakers can better understand the financial position of their communities and factors as wide-ranging as tax bases, municipal expenditures and state aid transfers.

Available resources in terms of assessed property value and other streams of revenue play a major role in the financial standing of cities and towns. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in 2017 Boston and Cambridge led the pack in the value of assessed property due in part to high housing demand and the concentration of large companies in both cities. However, other hubs for industrial parks and industry outside the metropolitan core also have significant assessed property values such as Canton or Marlborough.

Property taxes in Massachusetts are governed in part by Proposition 2 ½ which passed in a 1980 referendum. Under the terms of the statute, the amount that property tax can increase in a given year is capped at 2.5 percent of the assessed value of all taxable property within the municipal limits. Excess levy capacity is the difference between the maximum property tax revenue a community is permitted to raise under Proposition 2 ½ rules (the levy limit) and the tax revenue actually raised. In terms of excess levy capacity, cities like Cambridge ranked near the top, with other mid-size cities like Canton, Marlborough, Quincy, Woburn and Lowell high on the list as well. Cambridge’s position is particularly unique, with resources equivalent to over 150 percent of its annual budget. Curiously, some small communities in Western Massachusetts also have significant resources relative to their budgets. One example is the tiny town of Monroe, likely due in part to its pumped storage hydroelectric plant.

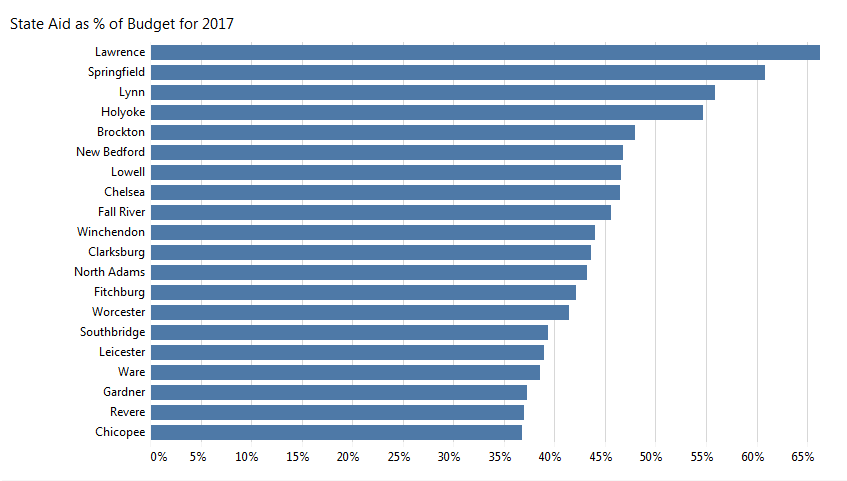

Many gateway cities witnessed a long-term erosion of tax bases as many formerly significant employers pulled up stakes throughout the deindustrialization of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. As they have worked to recover their tax bases by attracting new industry, while meeting local commitments, they often rely heavily on state aid. In 2017, Lawrence drew over half its total budget from the state—over 65 percent. Springfield was the only other city above 60 percent. Lynn, Holyoke, Brockton, New Bedford, Chelsea, Chelsea, Fall River, Fitchburg and North Adams were also above 40 percent. Not all communities receiving significant state aid are cities. In fact, the small towns of Winchendon and Clarksburg also stood above 40 percent.

Massachusetts communities are required to balance their budgets, but still accumulate significant debts. Cities, in particular, often have significant debt service. Boston and Worcester each faced sums of $172 and $112 million in 2016. Given a 2017 population of 685,094 in Boston and 183,677 in Worcester, a simple calculation reveals an approximate Boston 2017 per capita debt service of $251 and $610 for Worcester. Other communities with comparatively high debt service include Cambridge, Springfield, Lowell, Newton, Wellesley and Framingham. In terms of both percent of its debt limit and debt service, Hingham stood out, with $104 million debt service nearly on par with the state’s two largest cities.

Breaking these numbers down further, what emerges is that many communities are spending millions of dollars a year just on interest as part of their debt service. In 2016 alone, Boston expended $52.5 million on long-term interest, while the remaining $119.8 million of its debt service was long term retired debt. Short-term interest payments are less common and tend to be small, between a few thousand and several hundred thousand dollars. In fact, Boston did not make any short-term interest payments in 2016.

Not all communities face significant debt. Many small towns in Western Massachusetts have no debt at all and 12 scattered across the state had less than $100,000.

Are there places where financial standing has significantly changed? Among gateway cities, Chelsea has seen some marked improvements between 2010 and 2015, as its free cash grew by tens of millions of dollars, ranking in third place for growth after Boston and Cambridge.

Financial stability also depends on factors such preparedness for future financial events. Many communities have stabilization funds, which can be used to set aside funds for planned expenditures—such as new fire trucks or a new school—or for serious national emergencies or financial catastrophes; sometimes nicknamed “Dust Bowl accounts.” In 2017, Cambridge, Springfield and Somerville led the pack in setting aside funds to stabilization accounts, all with sums above $30 million.

About MassAnalysis

MassAnalysis is a powerful tool for comparing Massachusetts municipalities across multiple categories to draw meaningful comparisons from diverse data. Citizens and policymakers can compare education, crime, financial strength, tax rates, revenues and expenditures to make sense of how communities are performing. Learn more at massanalysis.com.