Underfunding OPEB – A Losing Strategy

In addition to pensions, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and its municipalities also provide their retirees with other post-employment benefits (OPEB), mostly in the form of retiree healthcare and life insurance. While these benefits have existed for many decades, the programs have not been sufficiently funded. As of June 2016, the best estimate is that the promised benefits are unfunded by $46.7 billion statewide.

Public employees who reach 10 years of service are entitled to receive a predefined set of benefits upon retirement. State retirees are entitled to life insurance and 80 percent of their healthcare costs from retirement to age 65, at which point they are transitioned to Medicare. At age 65, jurisdictions also subsidize supplemental Medicare coverage. The state requires local retirement systems cover at least half the cost of benefits, so some towns such as Andover have begun to reduce the size of the benefits they provide to retirees.

Once earned, the benefits represent a liability to be paid for many years. While the majority of the liability has been disclosed in financial statement footnotes, beginning in 2018 the entire net liability will be reported on governmental balance sheets.

There are two ways that governments structure their OPEB funding schedule: prefunding and pay as you go (PAYG).

Prefunding

Governments that prefund invest enough money at the time they are earned to cover OPEB liabilities. Using expectations about future healthcare costs and mortality, actuaries can calculate how much OPEB will cost them once retirees are entitled to receive benefits in, say, 20 or 25 years. The state or municipality can then determine how much money it must set aside in a trust fund to cover those future costs. Massachusetts has a State Retiree Benefits Trust Fund (SRBTF) to which the state makes periodic contributions. SRBTF invests all its assets with Pensions Reserve Investment Trist (PRIT), which manages a large portion of state pension funds.

In prefunding scenarios, governments discount expected future benefits using the estimated yield on current investments to determine the present value of its liability. Massachusetts has estimated that yield to be 7.5 percent.

For example, if a plan were sufficiently funded, using 7.5 percent as the discount rate, $100 in benefits due in 20 years, would require a $24 dollar investment today to fully fund obligation. If Massachusetts had set aside a more significant amount to provide for OPEB, applying a discount rate of 7.5 percent to expected future benefits would result in a liability of $10.9B (pdf page 5 of document). However, Massachusetts has insufficiently funded OPEB and, as of January 1, 2016, had only $760 million in its OPEB trust.

Pay As You Go

In effect, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts uses PAYG, under which healthcare costs are paid out of current government appropriations as benefits are consumed. Without significant funds set aside to earn investment income, this approach is extremely risky and can compromise governments’ future financial health.

According to new regulations introduced by GASB 74-75, PAYG plans should use a more conservative blended discount rate based on 20-year municipal bond yields and the expected long-term rate of return on investments in the trust According to the Bond Buyer 20-Bond GO Index, the 20-year yield yields are currently around 3.75 percent. Using a lower discount rate translates to a much higher OPEB obligation

For example, the difference between using a 4.5 percent rate, as determined in the Commonwealth’s recent actuarial report, and 7.5 percent would have been over $6 billion for unfunded state OPEB liability in 2016. According to the actuarial report published by the consultant Aon Hewitt (pdf page 5 of document) with a 4.5 percent discount rate, the state’s actuarial accrued OPEB liability would be $17.1B. The state has set aside and invested only $760M to provide for the liability, leaving over $16.3B unfunded. Using a 7.5 percent rate would reduce the unfunded liability to $10.1B.

How did we get here?

Simply put, the state started late when it comes to paying for current services and never invested in catching up. Every year, retired state employees consume healthcare benefits that they earned 20-30 years ago. Because those benefits were not prefunded, the state has to pay out of pocket for them now, which consumes a larger and larger portion of the budget. To transition to a prefunded plan, Massachusetts would not only have to continue paying these costs, but also fund the liabilities being earned today.

The Plan

In 2004, in response to concerns that OPEB liabilities were not properly represented on public balance sheets, the Governmental Accounting Standards Board passed GASB 43 and GASB 45. Under these standards, large pension systems, starting in 2006, were to create an unbinding funding schedule that would fully pay down their unfunded liabilities over a 30-year period.

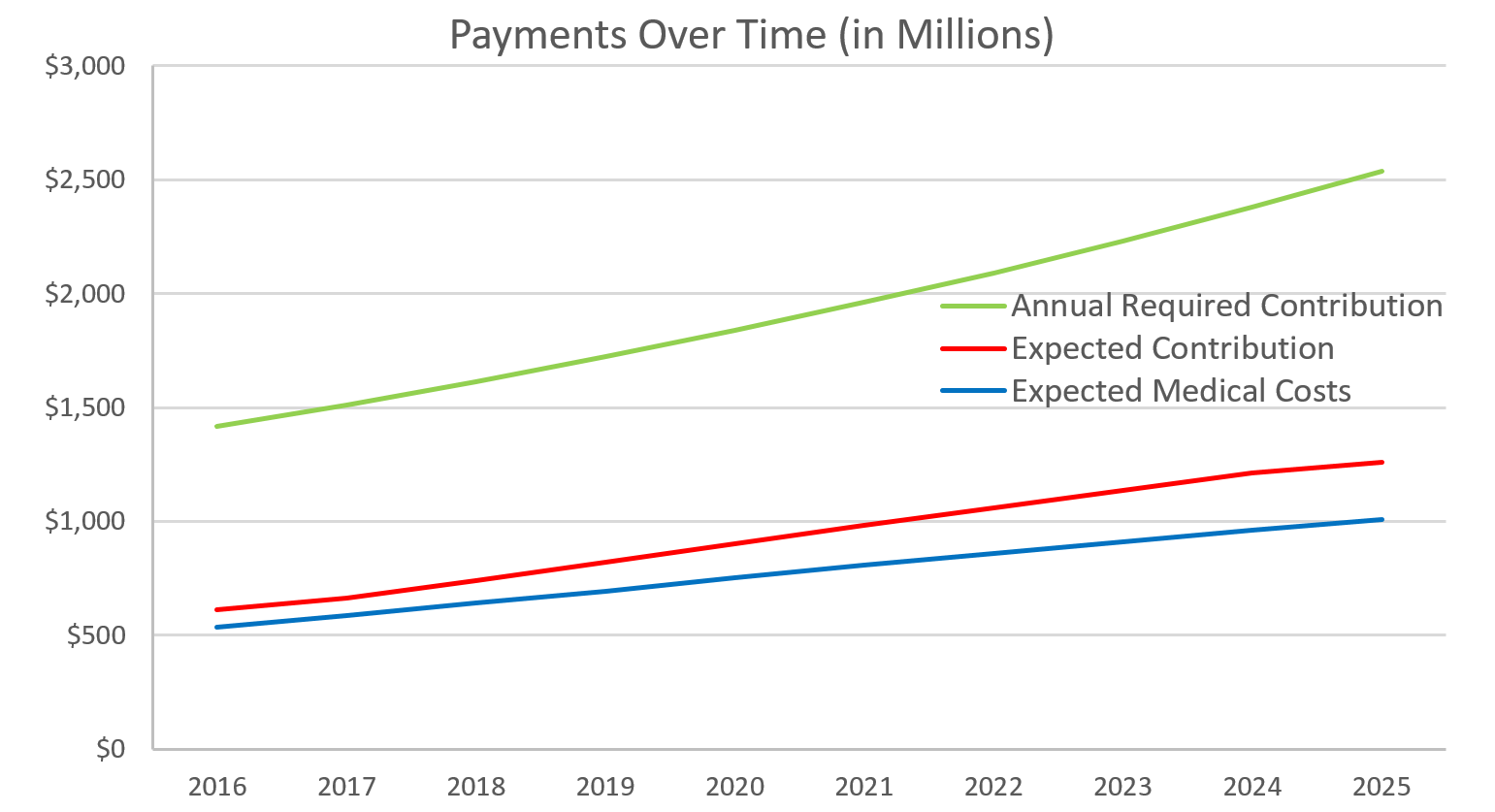

The graph above is constructed using data from the 2016 actuarial report. The green line is the annual required contribution (ARC). It represents how much the Commonwealth would have to pay each year to fully prefund its OPEB liabilities by 2037, assuming it has fully funded the ARC every previous year. The ARC includes both the actuarial liability for benefits earned in the given year and a portion of the previously unfunded liability on a 30-year payment schedule.

The red line is how much Massachusetts is expected to actually contribute toward the ARC. Current Bay State contributions consist only of the annual healthcare costs and money that goes to the trust fund from tobacco settlements. Tobacco money is expected to increase to a maximum of $250 million by 2024. This is well below what would be required to prefund the system within a reasonable timeframe. The actuarial report states that “the Commonwealth originally assumed to fund approximately 80 percent of the ARC.” Whether it follows through on this commitment has yet to be seen, however current projections make this seem highly unlikely.

What about city and local plans?

Many local plans are in much worse shape than the state plan. While the state retirement system has $16.3 billion in unfunded liabilities, PERAC estimates unfunded actuarial liability for OPEB benefits across the state, including municipalities, to be roughly $46.7 billion as of September of 2016.

Unlike the Commonwealth, many of these districts have not started a trust fund. According to PERAC, only 30 percent of regional and 60 percent of municipal retirement systems have established or plan to establish an OPEB trust fund. This means that at least 70 percent of regional and 40 percent of municipal retirement systems are fully PAYG with no plans to switch.

The City of Attleboro, for example, has not established an OPEB trust fund. In 2016, the city only paid $7.52 million of the $18.6 million ARC and prefunded no future obligations. According to PERAC, a fully funded prefunded OPEB plan for the city would need $142 million in assets. Thus, not prefunding costs the city $4.26 million each year, or 3 percent of the $142 million in lost returns. Their actuarial liability is $90 billion higher than it would be with a prefunded plan. The city has no plans to prefund OPEB in the future.

New Bedford, on the other hand, has a trust fund but chronically underfunds it. In 2016 New Bedford had an adjusted ARC (OPEB Cost) of $31.5 million, $16 million of which would go to pay benefits, with $15.5 million being paid into a trust fund. Unfortunately, New Bedford only contributed $759,000 to the fund, about $14.7 million short of what was necessary. Underfunding the OPEB system could cost the city over $7 million per year in lost returns and increase liabilities by $180 million.

These are only two of the almost 450 Massachusetts entities with an OPEB plan. The complete list and their funding status as prepared by PERAC can be found here. This includes every city, town, and district in Massachusetts. At the time this report was compiled, 249 of the plans had no assets whatsoever, meaning none of their obligations were prefunded. Taxpayers and future taxpayers can look and see if their district is doing enough – or anything – to begin to sustainably fund OPEB.

What can be done?

In March 2016, a committee commissioned by the town of Andover to look at potential solutions to its growing $184 million in liabilities released a report with a list of recommendations. These suggestions were ultimately adopted by town leadership and could serve as a model for other districts across the state.

First and foremost was a suggestion to create a plan to fully fund their OPEB plan and commit to a funding schedule. This would eventually lead to a prefunded plan that could take advantage of higher investment returns as well as stabilize outgoing payments in the long run.

More controversial was the suggestion to increase retiree healthcare contribution rates from 20 percent to 50 percent over seven years. This alone would reduce the current $184 million in liabilities by $53 million.

The town would also limit eligibility for OPEB benefits to those who have worked for at least 25 years, rather than 10, and only those who worked full-time rather than part-time. There are many more suggestions on the list, but the general idea is that towns must be willing to contribute more money into a trust while retirees must simultaneously be willing to accept reduced benefits.

Not everyone agrees with Andover’s actions, however. After adopting them, Andover was hit with a class action lawsuit from retirees who believe the town is not paying the benefits it promised. The outcome of the lawsuit will likely set the precedent for what municipalities or the state are able to do to reform OPEB going forward.

Conclusion

Sometimes it is hard to think about the long term when we face so many immediate budgetary challenges. Prefunding OPEB costs a significant amount of money now and may take 30-50 years to fully achieve. Those currently in power likely won’t be around to enjoy the benefits of a prefunded OPEB plan, while they would certainly feel the pain of diverting money away from infrastructure, education, and other essential services. Yet, this is an important sacrifice we need to make for the future of the Commonwealth.

The state is already feeling pain as a result of its irresponsibility. In June, Standard and Poor’s cited concerns that OPEB liabilities have grown to 12.2 percent of the state budget and are continually increasing in its decision to downgrade Massachusetts’s credit rating.

The state and local systems should adopt at least some amount of prefunding, even if they do not contribute 100 percent of the ARC. Continuing to fund only PAYG is not sustainable. Plans should also consider adopting some or all of the steps that Andover has taken to ensure a sustainable future.

If we don’t do anything, it will be the next generation that bears the cost. According to the OPEB Commission, between 2002 and 2009, healthcare costs in the Commonwealth’s 50 largest municipalities grew by 85 percent, while property taxes grew only 42 percent. If this trend continues, OPEB will gobble up an ever-larger portion of the state budget.

The question isn’t whether the $46.7 billion will be paid, but how and when. Massachusetts can make sacrifices now and play the long game, or it can wait, forgo the returns, and hope the next generation is able to pick up the bill.

Joshua Beck is a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern studying computer science and economics at Brown University.