“Catch-22” of State Prevailing Wage Law Prevents Flagger Reform from Achieving Significant Savings

State law sets prevailing wage at highest collectively bargained rate, which ties civilian flagger pay rates to police detail rates

Read about this report in the Boston Herald.

BOSTON – The unusual way in which Massachusetts determines prevailing wages and the fact that civilian flaggers are subject to state prevailing wage law explain why a 2008 law that ended the Commonwealth’s status as the only state to require police at road construction projects has failed to generate substantial savings, according to a new policy brief published by Pioneer Institute.

Massachusetts is one of just five states to stipulate that prevailing wage – which establishes pay rates on public construction projects – be set at a level at least equal to rates established by collective bargaining agreements with organized labor in the area. The federal government and the other 23 states with prevailing wage laws use both collectively bargained wages and market rates in the area to set prevailing wages.

“The Catch-22 is that since Massachusetts law sets pay at the highest collectively bargained rate in a geographic area, rates for civilian flaggers are effectively set by the rate paid to police performing flagger duties,” said Greg Sullivan, who co-authored “What Ever Happened to Flagger Reform?” with Pioneer Research Assistant Michael Chieppo.

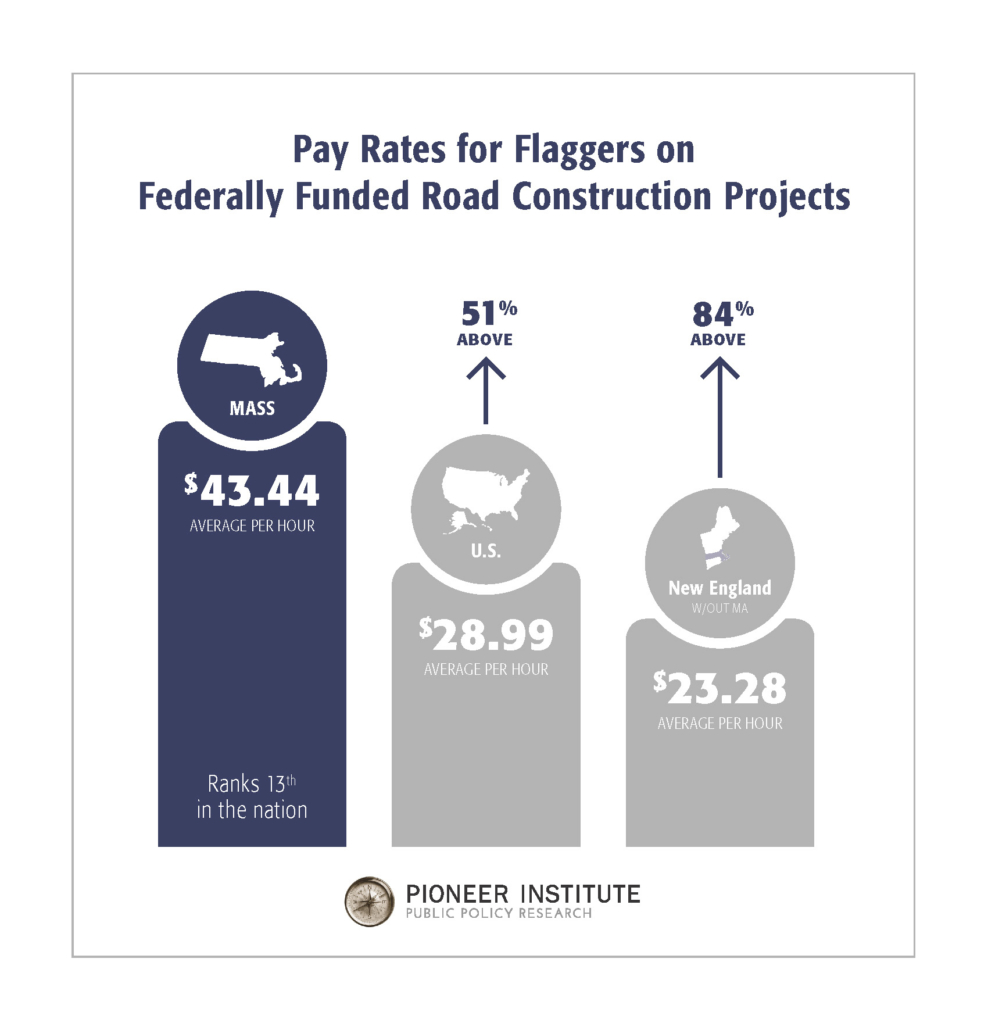

The Commonwealth’s decision to include flaggers under prevailing wage means that on federally funded road construction projects, the $43.44 per hour flaggers earn ranks 13th in the nation, about 51 percent above the national average of $28.99. Massachusetts’ pay rate is 84 percent above the $23.28 hourly rate of the other five New England states.

A survey of wage and fringe benefit rates paid to flaggers in 10 Massachusetts communities on state and locally funded projects revealed rates very similar to those paid on federal projects.

In most cases, flagger rates agreed to by municipalities and police unions are higher than those earned for normal police work. In addition, officers generally receive time and a half for working nights, weekends and holidays. They are paid for four hours if they work four hours or less, and for eight hours if they work between four and eight hours.

Under the federal Davis-Bacon Act, contractors on federally funded projects must pay wages and fringe benefits, but workers already receiving fringes from their employers are only entitled to the wage rate. But in Massachusetts, police working flagger details are paid a single flat rate despite the fact that they already receive fringe benefits from their employer.

Not surprisingly, savings from the 2008 law have not been significant. After three years, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation said it had saved $23 million. The reason any money was saved is because civilian flaggers are only paid for hours worked, as opposed to the four- and eight-hour minimums police flaggers enjoy.

The minimal savings has translated into scant use of civilian flaggers. In October 2011, the owner of one flagger contracting company was quoted as saying he had yet to sign his first flagging contract in the Commonwealth. Two others have simply given up trying to contract for civilian flaggers in Massachusetts.

Sullivan and Chieppo urge that the determination of prevailing wage for flaggers in Massachusetts be de-linked from police union contracts, which would lower the prevailing wage, increase savings and create an incentive for municipalities to use civilian flaggers.

“The intent of prevailing wage laws is to prevent companies engaged in public construction from paying workers less than the market wage for similar work in the area,” said Pioneer Executive Director Jim Stergios. “But in Massachusetts, the intent is to require state and municipal taxpayers to pay the highest wage rather than the prevailing wage.”

About the Authors

Gregory W. Sullivan is Pioneer’s Research Director. Prior to joining Pioneer, Sullivan served two five-year terms as Inspector General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and was a 17-year member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Greg holds degrees from Harvard College, The Kennedy School of Government, and the Sloan School at MIT.

Michael Chieppo was a 2018 summer intern at Pioneer Institute. After a gap year, he will enter UMass Lowell in September 2019 to study environmental science in hopes of pursuing a career as a science communicator and writer.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.

Get Updates on Our Transportation Research

Related Research: