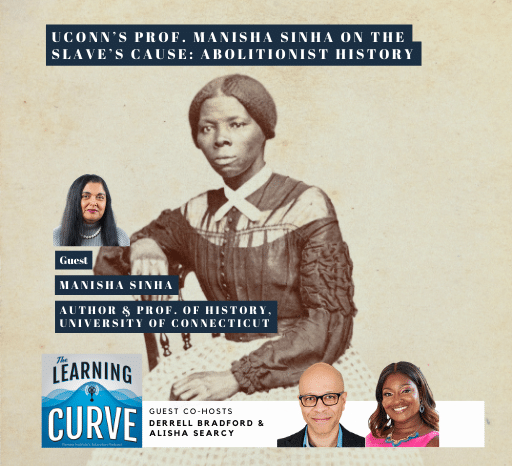

UConn’s Prof. Manisha Sinha on The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition

/in Featured, Podcast, US History /by Editorial StaffThis week on The Learning Curve, guest cohosts Derrell Bradford and Alisha Searcy interview professor Manisha Sinha, the Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut and an expert on slavery and abolition. She discussed the influential figures and seminal events that created the abolitionist movement. Professor Sinha described the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade, Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad, the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and other key moments in the fight to end slavery. She closes with a reading from her book The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition.

Stories of the Week: Derrell talks about a recent New York Times article highlighting the declining academic progress by students despite billions in federal funding; Alisha discusses an Education Next article on the portrayal of traditional public and charter schools in ABC’s TV series Abbott Elementary.

Guest

Manisha Sinha is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut, and a leading authority on the history of slavery, abolition, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. She taught at the University of Massachusetts Amherst for over 20 years, where she was awarded the Chancellor’s Medal. Professor Sinha is the author of several award-winning books, including The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina and The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, which was long listed for the National Book Award for nonfiction. She has also written for The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time Magazine, and CNN. Professor Sinha has been interviewed on NPR, NBC, BBC News, C-SPAN, Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show, and was an advisor and on-screen expert for the Emmy-nominated 2013 PBS documentary, The Abolitionists. She was born in India and received her PhD from Columbia University, where her dissertation was nominated for the Bancroft Prize.

Manisha Sinha is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut, and a leading authority on the history of slavery, abolition, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. She taught at the University of Massachusetts Amherst for over 20 years, where she was awarded the Chancellor’s Medal. Professor Sinha is the author of several award-winning books, including The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina and The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, which was long listed for the National Book Award for nonfiction. She has also written for The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time Magazine, and CNN. Professor Sinha has been interviewed on NPR, NBC, BBC News, C-SPAN, Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show, and was an advisor and on-screen expert for the Emmy-nominated 2013 PBS documentary, The Abolitionists. She was born in India and received her PhD from Columbia University, where her dissertation was nominated for the Bancroft Prize.Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a transcript here:

The Learning Curve, transcript. Guest Manisha Sinha. July 26, 2023.

Alisha: [00:00:00] This is another edition of The Learning Curve, and I am your co- host, Alisha Thomas Searcy, proud to be with another guest host today, my friend Derrell Bradford, president of 50Can. Hey, Derrell.

Derrell: Good to be here, Alisha. How are you?

Alisha: I am wonderful. Great to be with you today. So I’m going to let you start with giving us the story of the week. What do you got?

Derrell: Yeah so, from the paper of record, the New York Times, I would encourage all listeners to have to read this with a hot cup of righteous indignation.[00:01:00] The headline is U. S. Students Progress Stagnated Last School Year Study Finds. Uh, the subhead, which is very telling is despite billions in federal aid, students are not making up ground in reading and math. We’re actually seeing evidence of backsliding. So this was an analysis of a report from NWEA which came out this week that basically tells us everything we knew was going to happen and had every opportunity to avoid. But have let happen anyway, and that is that after the historic learning losses, yes, I’m calling them that, of the pandemic, which of course most acutely affected low income kids of color in school districts that were remote the longest, highly urban, where the, you know, sort of differences in achievement were most pronounced already that the federal aid that was appropriated by Congress, 190 billion by some accounts to help those kids catch up [00:02:00] has not helped them catch up.

And I would just say that the most startling bit of data is that the kids who are most behind are the oldest, who also have the hardest subject matter to catch up on and the longest way to go. This is the response, I would say, to the school closures of the pandemic and the learning loss.

That as a result of it, is one of the greatest domestic policy failures of our time. I think the mistakes of the last three years will be with us for the next 30. I think there will be a sort of a cascading series of policy impacts that happen to these kids in life. That will be both expensive financially and personally to them.

And the fact that there is so little discussion about this at the federal level, not only the fact that basically this money’s been put in a wheelbarrow and, set on fire but [00:03:00] also that American students the neediest of them for the most part, will be paying for this failure for the rest of their lives, is a great tragedy that should be on everyone’s mind and at the front of every discussion.

So that’s my sad piece of the week.

Alisha: I know it is sad and it’s frustrating too. You know, as you were talking, it reminded me of the cheating scandal in Atlanta public schools.

Derrell: Yeah, I remember that.

Alisha: Right, so there was lots of consternation about teachers being arrested and jailed and all of that. And we love our teachers and we can understand somewhat. But the connection that I’m making here is the impact that the cheating on the students had will last forever, and it’s very similar to what we’ve done to kids during the pandemic. And the only thing I would add to that, I don’t have the research here, but I would also argue that the reason why the older kids have probably been even more negatively affected is [00:04:00] because some of their schools were already failing them prior to the pandemic.

Derrell: I think that’s a strong hypothesis.

Alisha: And so it’s not a surprise, but it’s deeply sad. And I would argue that not just at the federal level, but even at the state level. I can’t tell you how many meetings I’ve sat in in the last couple of weeks alone, talking about reading scores, the science of reading, teaching teachers, how to teach reading.

And no one seems to be concerned. I think it’s a crisis, right? That only 30% of our kids nationwide are reading at grade level when it comes to fourth grade NAEP scores. I just don’t get it. And so it is sad and it’s frustrating and I’m hoping that this story is a call to action.

Derrell: Now, I know you’re going to cheer us up with your story now.

Alisha: I’m so not. But this is a little bit lighter. I want to talk about a story that’s in Education Next called, “Does Abbott Elementary get teaching in an inner city public school right?” And so I [00:05:00] picked this story because I used to watch Abbott Elementary.

I loved the show. I was quite entertained by it. And I think Robert Pondiscio, I hope I’m saying his name correctly.

Derrell: That is how you say it.

Alisha: Okay, good. He essentially says it’s entertainment, get over it, especially you charter people. Obviously I’m paraphrasing. And so here’s the deal, I’ve never been a classroom teacher and so I will just start with that for those who have and you know, need that to, make your arguments.

But I have been a superintendent. And I can tell you that many of the experiences in comedy that have been in Abbott Elementary have resonated with me. I really have been entertained, but also recognize some of the truth in the experiences of the new teacher who has all the ideas, but gets a wet towel to dampen all of that excitement when she realizes the lack of resources at the school or whatever, you know, the list goes on.

But I stopped watching because… Of the [00:06:00] misinformation and what I believe to be the mischaracterization of charter schools. And Derrell, I know you know this because we’ve been on the proverbial battlefield when it comes to charters. And it’s really just about fighting for more options in the right path for our kids.

But because we’ve had these political battles and some of us have wounds to show for it. You can’t use a national platform to further misinform and demonize charter schools. And I think that’s what Abbott Elementary does way too often for my taste. So I wish to show well, I think it does highlight that we have to support our public schools, that we have to support our teachers.

And I don’t, when I say support, I’m not talking about more money. I’m talking about making sure that they have the resources that they need, talent, et cetera, to be successful. And I think it could have the same effect without showing charter schools to be this evil place at snatching kids.

I totally agree

And so again, I wish them well, but I, I want them to do better in that regard. And. [00:07:00] Wouldn’t it be very cool to have someone like a Derrell Bradford or an Alisha Thomas Searcy to be in the writing room to help them tell the right stories about charter schools? So if you’re listening, that’s my ask of you.

Derrell: As a former magazine editor and an English major who graduated with a concentration in creative writing, I would very much, I would very much enjoy that.

Alisha: There you go. Perfect. Let’s make a call. Let’s see what we can do.

Derrell: And one more thing for folks listening. Debbie Veeney, who works at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, actually wrote a wonderful retort to this emerging anti charter storyline on Abbott.

And I would encourage anybody who’s interested to read

Alisha: Great. So after the break, we have the great pleasure of talking to professor Manisha Sinha and Derrell is going to introduce her in just a moment, but we’re excited to see what she’s talking about.[00:08:00]

Derrell: We’re delighted today to have professor Manisha Sinha. Here to talk to us about her book. She is the James L and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut and a leading authority on the history of slavery, abolition, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. She taught at the University of Massachusetts Amherst for over 20 years, where she was awarded the Chancellor’s Medal. Professor Sinha is also the author of several award winning books, including The Counter Revolution of Slavery, Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina. And The Slave’s Cause, A History of Abolition, which was long listed for the National Book Award for Nonfiction.

She has also written for the Times Literary Supplement, the New York Review of Books, the Wall Street Journal, [00:09:00] the New York Times, the Washington Post, Time Magazine, and CNN. Professor Sinha has been interviewed on NPR, NBC, BBC News. C SPAN, Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show, and was an advisor and on screen expert for the Emmy nominated 2013 PBS documentary, The Abolitionists.

She was born in India and received her PhD from Columbia University where her dissertation was nominated for the Bancroft Prize. Thank you for being here with us today, Dr. Sinha.

Manisha: Thank you so much for having me.

Derrell: Your book, The Slave’s Cause, is a comprehensive volume. Look, you can, even if you look at the book reviews on Amazon, people use the word comprehensive all the time.

What I would say is an underappreciated topic in U.S. history. Would you share some of the main themes regarding the black and white male and female religious and secular leaders and their sort of convergence in the abolitionist movement?

Manisha:That’s an excellent question. When I started writing [00:10:00] this book on abolition, I realized that we do not need to think about abolitionists as some sort of individualistic moral do-gooders, you know, individual benevolent reformers, which is the way they are commonly portrayed in U.S. history textbooks but to really see it as a radical interracial social movement that included ordinary American citizens, and those who were not counted as citizens. The enslaved, men and women, black and white, and that’s what makes abolition such an interesting radical social movement because it created a space for the disenfranchised and it allowed them to push at the boundaries of American democracy, both in terms of challenging the existence of racial slavery, but also in terms of demanding equal rights, equal citizenship rights in this country.

Derrell: In my daily work, we work with advocacy campaigns all of the time. [00:11:00] And a lot of the time, you know, you’re trying to change an idea like a social system, or you’re trying to change an economic system in a lot of respects.

And according to historians from 1444 to 1870, the trade of enslaved was central to the economics of the Western world, you know, reports indicate that 54,000 voyages brought 13 million enslaved Africans to the New World, including 4 million to Portuguese Brazil, 2. 5 million to Spanish America, 2 million to the British West Indies, and 500,000 slaves to British North America and the United States.

This was a massive, multinational, global economic alignment that abolitionists were trying to undo. Can you give some deeper context to kind of like the economic alliances that, these folks were trying to disrupt?

Manisha: Yes, you know, that’s again, a very [00:12:00] important question because if you look at the dimensions of the Atlantic slave trade, as you mentioned, it’s like a world historical event, right?

It involves the destinies of so many different continents. In the West, and it actually involves a long time period, centuries. And this is where the abolition movement gets its start in critiquing this commerce in human beings as they recognized it. And one must understand that. The Atlantic slave trade was very much linked to the emergence of the modern West, which has always been multiracial, not to mention indigenous peoples in the Americas who were also subjected to various forms of servitude and enslavement, and then millions of people of African descent, mainly from the west coast of Africa.

Towards the end of the trade, they even sort of rounded out and tried to go to the east because they were exhausting [00:13:00] their supplies of enslaved people, literally. When we think about it this idea of unfree labor is at the heart of slavery. It’s at the heart of the emergence of the Americas, you can even see this in terms of the development of capitalism in Europe. If you see which countries dominate the slave trade at different times, you can literally figure out which countries were at the forefront of economic development. So it goes from Italian city states to the Iberian Peninsula, then to the Dutch, then on to the French and English, and it’s really connected to their economic rise.

So when abolitionists confronted the slave trade, and I must say that the numbers have been increasing in the transatlantic slave database. The numbers are inching towards 15 million for the United States, more towards 600,000. But regardless of the numbers, the first thing that abolitionists [00:14:00] really saw was the cruelty, the inhumanity of the trade. And the people who first protested against it were those who were enslaved in the West Coast of Africa. So I begin my book by talking about Africans who resisted their enslavement as the original abolitionists, both in the West Coast of Africa, but also in shipboard rebellions in the slavers coming over the Atlantic.

And then of course it becomes a site of cruelty that many other abolitionists at that point focused their attention on. Before slavery, they focused their attention on the inhumanity of the slave trade. And it is no wonder that the first thing to be abolished is the transatlantic slave trade by the British and by the United States in 1808.

My book begins with the idea that we often talk about African participation in the Atlantic slave trade. We rarely talk about [00:15:00] African resistance to the slave trade and that we must be talking about that too.

Derrell: You obviously mentioned Great Britain and the British Empire. I wanna make sure I get his name right, Olaudah Equiano?

Manisha: Yes. Olaudah Equiano.

Derrell: Was a Nigerian born former slave who was among the leaders of the British anti-slavery movement in the 17 eighties. His 1789 autobiography. The interesting narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano, I’m working on my phonemes here, helped secure passage of the British Slave Trade Act 1807. Can you talk a little bit about his experience and his unlikely alliances with William Wilberforce and other others in the British parliamentary system who were to abolish the slave trade in, Britain and the Empire.

Manisha: Absolutely. You know, I tried to center people of African descent. African Americans and even Afro [00:16:00] British abolitionists like Olaudah Equiano in my book. I make the case that these figures have been largely forgotten in the history of abolition and that they were in fact central to the movement to abolish the slave trade.

It’s not to say that we need to necessarily displace people like William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, but to understand that these movements took off because of connections between black and white abolitionists. So, Olaudah Equiano, for instance of course, we’re talking about pre colonial Africa.

You’re talking about pre modern Africa, was from the Igbo people, and he remembered his origins there. And he describes the middle passage, the terrible middle passage over the Atlantic Ocean. His slave narrative was one of the first ever published. There were a few who had published before him, but his is the one that becomes extremely popular and becomes very important. It runs into several editions. It [00:17:00] converts people. He goes on lecturing tours, what we would call today book tours. He has subscribers to his narratives. It is published in the United States by a radical artisan New York group. So if you look at the publishing history of Olaudah Equiano’s narrative, you realize the tremendous impact it had in the movement against the slave trade.

And there are a group of these Afro-British abolitionists whom I talk about in my book, people like Etoba Quagano, Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho. We’ve forgotten these people because we never think of the early modern West as a multiracial, multicultural space. And when we talk about its radical democratic traditions, the tradition of abolition, these people play an outsized role.

Now there has been a scholar recently who has questioned Equiano’s narrative as he was questioned when he actually wrote that narrative, a literary scholar who thinks he found a smoking gun by finding his [00:18:00] baptism record and saying, well, he made up that whole story that he was born in Africa, et cetera.

And that, in fact, this baptism record shows that he was born in fact in South Carolina. and his name is Vincent Coretta, the man who made this claim. Now, unlike literary scholars, historians don’t just take one piece of evidence and say, oh, this is definitive. We look at what is going around it.

And we know that people of African descent, when people registered them, they often wrote different names for them. For instance, Olaudah Equiano’s given name was Gustavus Vasa, which was named after the Swedish king. Enslavers liked to do that. They named their enslaved people Caesar or, you know, Gustavus Vasa, as if to make fun of their status as especially disempowered people with these big names.

But when Equiano got his freedom, won his emancipation, he chose to use his original African name, which was Olaudah Equiano. So [00:19:00] historians have said, look, this happened all the time. There would be a person who would record people’s, especially black people, they would record their names differently.

They would put their last port of embarkation as their birthplace because they couldn’t care less, when they were born in Africa, so we have to be very careful with evidence like this. And in my book, I come out against this theory that Equiano had fabricated his entire narrative because he clearly had not and Black people’s testimony against slavery, especially abolitionist testimony, has always been questioned for all kinds of reasons.

And I think Equiano’s narrative was important. He was in fact, a link to many of the important abolition cases that were fought in Britain, the Zong case and the Somerset case. All these cases were cases that Equiano and other people of African descent brought to the attention of white abolitionists, and we should be able to tell that backstory.

Derrell: Dr. [00:20:00] Sinha, I’m going to hand you off to Alisha.

Alisha: Thank you, Professor. It’s an honor to talk to you. And it’s very timely for me. My family and I recently visited the African American Museum in Washington, D. C. I think it was last week, and I’m not sure if you’ve been there yet. it’s three or four floors, maybe five.

After I left the bottom floor, which talks about slavery and enslaved people. I had to leave, couldn’t take it after a couple of hours, just, you know, you learn some things in history, in school it’s something else when you are confronted with that and walking through these rooms and learning of the experiences and how people were treated as fodder and animals and so it’s, it’s very powerful to me to be able to speak to you in this moment and to learn about your work. So thank you for the enormous amount of research that you’ve done and just the body of work that you’ve contributed here. Also a little personal note. I’m about to ask you about [00:21:00] Phyllis Wheatley.

And I just want to share this little story. One of my things is in theater, but the way I got into theater was being able to be Phyllis Wheatley in the Black History Show in fourth grade. So this is a little bit of a full circle moment for me. But it really speaks to an, even in fourth grade, learning about an enslaved woman who could read, right?

Which we know has been forbidden. in the 18th century, New England was an epicenter of the transatlantic slave trade and later became the home for the radical abolitionist movement in the US. And so could you talk about New England, slavery and figures like The Boston poet Phyllis Wheatley and early 19th century Massachusetts based abolitionists, including writers and activists, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, just to name a few.

Manisha: Exactly. [00:22:00] Thank you, Alisha, for your question and for sharing your. Your memories, you know, slavery, holocaust. When you go to museums that deal with these subjects, you really confront crimes against humanity and sometimes they’re difficult apart to confront, but something that I think we need to, especially with people may not be aware of these histories just so that they may never be repeated again. and you’re right, you know, when we look at New England, you know, we forget that slavery was legal, that Rhode Island and Massachusetts participated in the state trade that these states became free only after the American Revolution and after the passage of judicial decisions or gradual emancipation laws.

That in fact, colonial slavery existed and Phyllis Wheatley was one of those people caught in colonial slavery. I mean, she came as a young child, right? She’s named Phyllis of the Slaver, in which she came on. And in New England, at least it was not [00:23:00] illegal to teach enslaved people how to read and write.

And some did learn how to read and write. Even in the South, they did, sometimes, even in the face of laws against literacy, but those were far more strictly observed in the south where they actually had those laws. But in New England, if you look at Phyllis Wheatley, for a long time, literary scholars may have studied some of her poetry, but historians tended to neglect her.

And when I was writing The Slave’s Cause, now they’re, you know, everyone’s jumped onto the bandwagon and their new books on Phyllis Wheatley left, right, and center, new biographies. But when I was writing The Slave Cause, I felt she had been neglected. I called her the foremother of the Revolutionary Abolition Movement because she is writing poetry talking about freedom, and letters talking about the claims of enslaved people to freedom and that you have to really read her poetry very carefully to see her in the abolitionist tradition.

And I saw this especially in the 1830s when [00:24:00] abolitionists are constantly reprinting her poems.

And the reason they did that was not just as a testimony to her genius, as they said, African genius, because she was a genius, right? You come as a six, seven year old and you master Latin and English and Greek and you’re writing elegies and poetry. That is the toast of the Atlantic world. She could have become a famous poetess and just stayed on in London when she went there, but she chose to come back to the United States and lend her voice to what she saw as her people.

When she was told to go back to Africa and she said, no, I’ve grown up here and they will look at me strangely. I don’t even remember those languages anymore. They will think I’m a barbarian. So, Phyllis Wheatley is a far more complex and deep thinker and writer than we have given her credit for, and that’s the case I made in my book.

Now we know somewhat of her life a little bit in marriage. A colleague of [00:25:00] mine has discovered papers that have shed light on her husband, John Peters, who was somewhat of a lawyer and a great defender of her. Unfortunately, Phyllis dies in 1784, but her works are kind of immortal, they live on.

I do want to make this point, that New England, of course, had colonial slavery and the persistence of unfree regimes and slavery even after emancipation sometimes, but it is also the hotbed of abolitionism as you put it, this is the place where you have the emergence of interracial radicalism which is pretty unprecedented and African Americans play a huge part in it.

I talk in depth about Black people in Massachusetts and Connecticut who sued for their freedom, who petitioned for their freedom, who, in my opinion, actually formed the first abolition societies, even before the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, which is seen as the first abolition society founded [00:26:00] by Quakers in the Western world.

So I think they are the ones who are seeding this ground for interracial radicalism, and it continues in the 1820s when David Walker migrates to Boston from North Carolina, and he writes an appeal to the colored citizens of the world. And so when Garrison publishes his paper, The Liberator, The first few issues of his paper are just devoted to looking at David Walker’s appeal, which is this radical abolitionist indictment of the slave holding republic.

And which really does a great job in putting forth a platform of militant black abolitionism. For the immediate abolition of slavery, not the gradualism of northern emancipation and for black rights. And it influences white radicals like Garrison. And that’s where the movement really takes off.

And they go and form the American anti-slavery society in [00:27:00] Philadelphia with other abolitionists more religiously inspired abolitionists from New York. And also the Quakers who led the, so the first wave of abolition in the revolutionary era. So we are really talking about a very complex movement in which African-Americans are playing leading roles, as tacticians, as theoreticians, as strategists.

And that’s why one of the major points of my book is to say we have to look at abolition and not just look at the central role of African Americans, but in fact, look at the central role of enslaved people themselves because before the Civil War, over 90% of the Black population was enslaved in the South.

Alisha: Just astounding, and I think you raise such a powerful point. I’m going back to that visit to the museum. I think they need another floor, right, just to dedicate to abolitionists, because there’s a part of our history that’s not [00:28:00] being told about the bravery and the heroism and the strategy as you, as you talk about.

And speaking of some of the things that we learn in history books. Many people know the name Harriet Tubman, who of course is a former enslaved person and later an abolitionist herself who escaped slavery in Maryland. We know that she made 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 people using the network of abolitionists and safe houses called the Underground Railroad.

So could you talk about her legendary leadership and the Underground Railroad, an interracial movement of anti slavery activism?

Manisha: Yes, of course. You know, when we think about the Underground Railroad, what I call the abolitionist underground in my book, you can trace it right back to the colonial era because enslaved people are voting with their feet, running away from slavery, right from the colonial era.

And this is how abolition really takes off and how abolition societies form [00:29:00] in order to assist these people who are contesting their enslavement. And we can see this going right back to the 18th century with outstanding abolitionists like Isaac Harper, a Quaker, John Rankin, a Presbyterian minister Levi Coffin, another Quaker.

But also African American abolitionists like David Ruggles, who develops these vigilance committees and works in them to really develop the ways in which assistance to enslaved people can be systematized. And now we get, of course, somebody like Harriet Tubman and some other abolitionists who are not content with sitting up north and waiting for enslaved people to make their way up, which is a very treacherous and dangerous proposition. A lot of people are re-enslaved and never make it to the north. And if you’re in the deep south, then it’s really tough and you have to be very inventive to escape to the north, right?

You think of the William and Ellen Proud [00:30:00] story, where she is so light skinned that she disguised herself as the master of her husband and they made their way over the Overground Railroad all the way from Savannah, Georgia to Boston Massachusetts. So, there were all kinds of strategies that enslaved people used, but there were people like Tubman who was in fact a fugitive slave herself, a self emancipated slave.

Garrison never liked to use the term fugitive. He said these are self emancipated slaves. Let’s not call them fugitives from the law, who were not content with simply freeing themselves or even their family members, as in the case of Tubman, but who repeatedly went back to the South and put herself in great danger to actually run, what they call running off slaves, running off people to the north.

That was a dangerous proposition and Harriet Tubman did that and earned the admiration of a lot of people, including John Brown, who called her General Tubman, because of her prowess and her [00:31:00] skills. There were other abolitionists who did this, other white and black abolitionists who did this, and some who were not that fortunate as Tubman.

Tubman never got caught, But these, some of these people actually got caught and died in prisons. And so you hear the story of Charles Tory, of Calvin Fairbank, all these people who are arrested and are rotting in Southern jails, sometimes right after the civil war, but with Charles Tory, he actually contracts tuberculosis and dies.

So this is a dangerous business. And Tubman had a price on her head. So if she got caught. not only would the captive get a reward, but she would face dire consequences. She had a lot of help. William Still, the black abolitionist who wrote the famous book, The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania.

Other Quaker abolitionists Maryland, like Thomas Garrett, who assisted her. So we have, in Maryland and Delaware, there were people who joined her network. There were three black people in Maryland and Delaware who were really [00:32:00] important to the success of the abolitionists underground. These are not one off stories.

These are very complicated stories. They involve a lot of different people. And to really appreciate the radicalism of abolition or of a figure like Tubman, we should know that full story. And it’s one of the reasons I devote so much time to talking about what I call fugitive slave abolitionists in my book.

Alisha: I’m so glad that you were doing that. I cannot believe that time is up, but we cannot let you leave, please, without reading a paragraph, maybe your favorite paragraph of this particular book. Would you do that for us?

Manisha: I’ll be delighted to do that. So I have a number of favorite paragraphs in the book, but for this, I think I will use this one.

Mainly because we’ve been talking about feudal slave abolitionists and my book talks a lot about fugitive slave narratives, which I say were the movement literature of abolition they were not as people try to say, ghostwritten by white abolitionists or shaped by [00:33:00] white abolitionists. These were brave black men and women who left behind a testimony of their words and I think we should understand it as such.

So, long before Frederick Douglass, you had many people of African descent writing about their experiences and this is what caught my attention and I’ll just. briefly read it to you. This is how the paragraph begins. It’s from the chapter on fugitive slave abolitionism. People of African descent wrote autobiographies from the early days of racial slavery.

Fugitive slave narratives published under abolitionist auspices, however, constitute a distinct genre. In the 1820s, former slaves such as Solomon Bailey and William Grimes published their narratives. Bailey’s narrative was published in London, And he hoped that it would lead to abolition in the Western East and the United States.

Now, while Bailey’s narrative reads like a spiritual story reinforced by the tragic deaths of his [00:34:00] children, he indicts slavery by telling the story of his quote, Guinea grandmother and mother who were held by a poor family and whose children were illegally sold. Even more than Bailey, Grimes shows slavery to be an unending catalogue of horrors.

Published first in New York in 1825, the work for which he obtained a copyright as a Black author, was republished in 1855 with a new conclusion. Grimes described his checkered life of freedom in Connecticut, where I teach, and his constant fear of being recaptured. In the conclusion, he delivers a damning critique of slaveholding republicanism, and I quote him, “If it were not for the stripes on my back, which were made while a slave, I would in my will leave my skin as a legacy to the government, desiring that it might be taken off and made into parchment, and then bind the constitution of glorious, happy, and free [00:35:00] America. Let the skin of an American slave bind the charter of American liberty.” When I read those words, it brought tears to my eyes. And I was just, I mean, this was such an indictment. Long before Frederick Douglass. You know, we hear about Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and all the famous people. We don’t hear about the countless black men and women who left a damning testimony.

And this is why my book ended up being so big and that’s why it’s always called comprehensive because I made sure that I was going to make sure that their words were heard today.

Alisha: I’m quiet because I just have no words. I am just speechless. That last part about leaving his skin, just, I don’t even, what do you say?

How do you feel? And just like you just tears came to my eyes as a black woman, right. In the United States of America to know that [00:36:00] this is. This is my history. This is my legacy. This is a story, and not a story like a fairy tale, but you know, history that speaks to the strength and endurance of black people in the spirit of overcoming.

And one of the things I find most interesting is that we weren’t supposed to be able to read and write. But those stories are written, and they are ours and it’s because of historians like you that those stories are being told, and that that part of history is not being forgotten. So for that, we say thank you, Professor, for joining us. This was incredible.

Derrell: Thank you, Professor. This was wonderful.

Alisha: And thanks for what you’re doing. Please continue to support us. Keep it up. We need you in this country in the world.

Manisha: Thank you so much. Thank you for having me.[00:37:00]

Derrell: My tweet of the week, and Alisha, I know you’re a great fan of the Edunomics Lab is about ESSER funds.

And it talks about how enrollment declines are about to slam headlong into running out of ESSER funds over the next year and a half. And I would encourage everybody to check it out primarily because ESSER funds are a great way to know about how school districts think about the world.

A person with sunglasses on down in a cave could have seen this coming, but for everybody in the policy world talking about not going over a fiscal cliff American school districts seem to have made commitments that are the equivalent of hitting the gas and riding right off of it.

I don’t look forward to seeing what’s going to happen in a year, [00:38:00] but you can certainly look at this tweet and find out.

Alisha: Absolutely. And I actually just finished the certificate program that they do through Georgetown, which is phenomenal. And one of the things that Marguerite talks about is this bloodletting that’s about to happen in ‘25, ‘26.

And I want people to understand what this means and, this is a short little blurb that we’re talking about here. But to your point, folks have got to look at how districts have spent their funds, in this article in particular, they’re telling folks, if you’re thinking about leaving education right now to find a new job, this is probably not the right time.

Because when all of this funding goes away and districts are trying to figure out how to pay for all the things that they’ve invested in, there are going to be less jobs because districts are going to be minimizing their staffs. Yeah. So just a word to the wise there, but this is a big moment.

And to your point, I really think all of us need to pay attention to those on the policy side to those who are in education day to day. And as I [00:39:00] said a while ago, CFOs at school districts need to be paying attention and even here in Georgia our revenues are still up and we’re still seeing a surplus, but that’s going to go away and we need to pay very close attention to how districts are spending their money answer the age old question, are we getting a return on our investment?

It has been an absolute pleasure to be with you, Derrell, and to hang out with you on The Learning Curve.

Derrell: Pleasure was all mine, Alisha.

Alisha: Thank you, thank you. We look forward to seeing you all or hearing from you all in our next episode.[00:40:00]

Tweet of the Week

ICYMI: As enrollment declines collide with expiring #ESSER funds, @K_M_Silberstein and @MargueriteRoza warn that the hiring spree of recent years is about to come to a halt. https://t.co/wewsIOTPtN @The74

— Edunomics Lab (@EdunomicsLab) July 6, 2023