Changes to the Confounding Massachusetts Estate Tax

A desire to make the Commonwealth more competitive and desirable to taxpayers has resulted in leaders on Beacon Hill proposing tax-relief plans. House Speaker Rob Mariano, Senate President Karen Spilka, and Governor Healy all have proposed different packages for the now long-overdue budget for FY2024.

While they each vary in size and focus, all include changes to the estate tax. It is one of the key drivers for the out-migration of taxpayers from the Bay State – incentivizing lawmakers concerned with competitiveness to alter it. If done correctly, an updated estate tax would encourage key demographics, like retirees and business owners, not to flee the state.

Overview of the Estate Tax

An estate tax is levied on the transfer of assets from an estate after the death of the owner. Massachusetts is one of only 17 states to still maintain an estate tax after a 2001 change in the federal tax code replaced the dollar-for-dollar credit with a deduction. Due to rapidly increasing property prices, the estate tax has become a more significant source of state revenue in recent years. In 2022, according to Pioneer Institute’s MassOpenBooks website, the estate tax generated $868 million, putting it as the 20th largest source of revenue, ahead of gasoline and cigarette taxes.

Problems and Solutions

There are two main issues with the current estate tax. As Pioneer has shown, the first is the low exemption threshold (the minimum valuation at which an estate can be taxed). At $1 million, it is tied with Oregon for the lowest exemption threshold. The second major issue not covered in the first blog on this subject is known as the “cliff effect,” which is when the estate is taxed on its entire valuation, not just on the amount above the threshold. This results in relatively meager estates having to pay thousands of dollars in taxes.

Current proposals focus on increasing the exemption threshold and eliminating the cliff effect. The legislature agreed to increase the exemption to $2 million, and to tax only the amount over the threshold. Governor Healy holds a stronger vision of reform than the legislature, recommending a threshold at $3 million and offering a nonrefundable tax credit up to $182,000 to eliminate the cliff effect.

Inter-State Comparisons

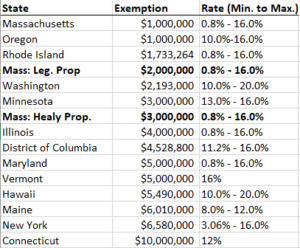

Figure 1: Exemptions and rate intervals for selected states arranged from lowest to highest exemptions, according to statues on January 1st, 2023. The proposed changes by the legislative houses and by the Governor are in bold, inserted for comparison. State data sourced from the Tax Foundation (table 36).

Figure 1 shows how the current Massachusetts estate tax and proposals to reform it compare with other states. The legislature’s proposals would place the Bay State between Rhode Island and Washington, yet it would still have the third lowest exemption rate. Healy’s plan would put Massachusetts on par with Minnesota, two spots below the median (D.C., at $4.53 million). Both propositions – especially Healy’s – are a considerable improvement to the current exemption threshold.

These reforms would make the estate tax less daunting to some retirees, business owners, and others affected by the tax. Combined with reforms to the capital gains tax and child tax credit, the Commonwealth could become a more appealing place for middle-income residents.

Peter Mentekidis is a Roger Perry Transparency Intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is a rising senior at Providence College, with a major in Quantitative Economics and a minor in Philosophy. Feel free to contact via email, LinkedIn, or writing a letter to Pioneer’s office.