Study: Financial Impact of Charter Schools Depends on Percentage of Funding Districts Receive from State

“Foundation” districts unaffected, but charter tuition may cause strain for fast-growing “above-foundation” school districts

Contact Jamie Gass, 617-723-2277 ext. 210 or jgass@pioneerinstitute.org

BOSTON – At a time when the funding of charter schools is widely debated, a new Pioneer Institute study finds that foundation districts are largely unaffected by students who choose to transfer to charter schools.

“So-called foundation districts receive most of their funding from the state, which means that the state effectively pays the tuition when students choose charters,” said Dr. Cara Stillings Candal, who co-authored “Charter School Funding in Massachusetts: A Primer” with Professor Ken Ardon. “But they can impact ‘above-foundation’ districts, particularly those that experience rapid enrollment growth.”

Watch: Dr. Cara Stillings Candal, Pioneer Institute Senior Fellow, explains charter public school funding in Massachusetts

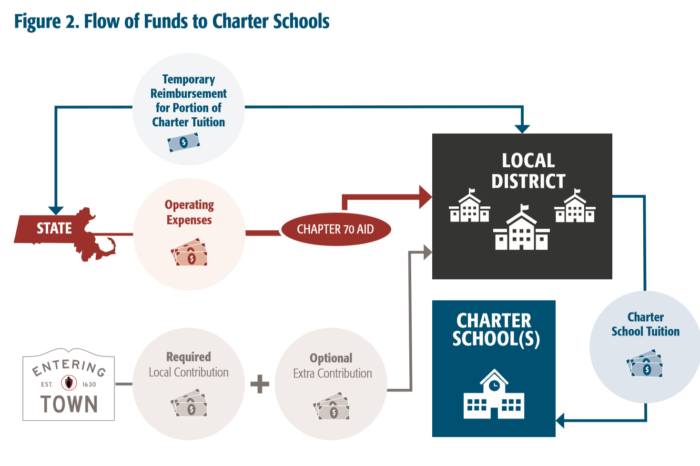

Under state law, the Commonwealth determines a foundation budget amount that each district needs to provide its students with an adequate education. It then calculates how much communities can afford to raise, and the state fills the gap between available local funds and the foundation budget amount.

The wealthiest school districts receive less than $2,000 per student in annual state funding, while the Commonwealth pays for the vast majority of K-12 public education in foundation districts.

When a student chooses to enroll in a charter school, the funding associated with that student flows from the district to the charter. Under state law, school districts are to be reimbursed 100 percent in the first year after a student leaves and 25 percent in each of the next five years, but over the last five years reimbursements have only been about 60 percent funded.

New Bedford, for example, is a foundation district. While it pays about $13,500 per student in annual charter school tuition, it receives about $12,000 of that from the Commonwealth. When even partial state reimbursements are added, the result is generally that charter tuition is entirely paid with state money.

How the charter school funding system affects above-foundation districts is less clear. On one hand, every time a student chooses to leave for a charter, any reimbursement received is extra money for a student the district is no longer educating. But some districts don’t average enough to cover charter tuition in annual state aid for each student.

In addition, a fast-growing school district can receive as little as $30 in state aid for new students, meaning the combination of enrollment growth and under-funded charter reimbursements could strain the district’s budget.

As the Commonwealth works to update its K-12 education funding formula, Drs. Candal and Ardon make several recommendations to improve the way charter schools are funded. To ease the strain on fast-growing above-foundation districts they urge the state to cover more of the cost of new students.

They also urge weighting charter school tuition based on the actual number of special needs students a charter educates. Under current law, funding to cover the additional expense of educating special needs students is based on the percentage of such students in the sending district, resulting in a windfall for charter schools if they educate a smaller percentage of special needs students and a hardship if they educate a higher percentage.

Among the authors’ other recommendations is that charter school reimbursements become part of the overall funding formula. This would make it much harder for them to be underfunded in a given year and also solve a perception problem created by the fact that while overall state aid is part of a larger formula, less-than-fully funded reimbursements are clearly visible.

About the Authors

Cara Stillings Candal is an education researcher and writer. She is a senior consultant for research and curriculum at the National Academy of Advanced Teacher Education and a senior fellow at Pioneer Institute. She was formerly research assistant professor and lecturer at the Boston University School of Education. Candal holds a B.A. in English literature from Indiana University at Bloomington, an M.A. in social science from the University of Chicago, and a doctorate in education policy from Boston University.

Ken Ardon received a Ph.D. in economics from the University of California at Santa Barbara in 1999, where he co-authored a book on school spending and student achievement. He taught economics at Pomona College before moving to Massachusetts, and from 2000 to 2004, Dr. Ardon worked for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the Executive Office of Administration and Finance. He is a professor of economics at Salem State University, where he has taught since 2004. Dr. Ardon is a member of Pioneer Institute’s Center for School Reform Advisory Board.

About Pioneer Institute

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.

Learn more about how you can help expand access to charter schools

Related Posts: