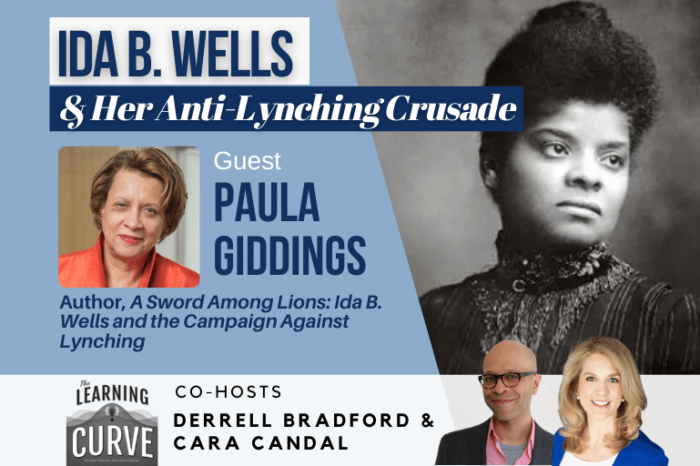

Smith College Prof. Paula Giddings on Ida B. Wells and Her Anti-Lynching Crusade

/0 Comments/in Academic Standards, Civil Rights Education, Civil Rights Podcasts, Featured, News, Podcast, Related Education Blogs, US History /by Editorial Staff

This week on “The Learning Curve,” Cara Candal and guest co-host Derrell Bradford talk with Prof. Paula Giddings, Elizabeth A. Woodson Professor Emerita of Africana Studies at Smith College, and author of A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching. Professor Giddings shares how her experience watching historic events like the Civil Rights Movement and Freedom Rides shaped her career in academia and journalism. She discusses her definitive biography of Ida Wells, a late-19th-century Black female journalist and writer who is an unsung figure in American history. She reviews Wells’ underprivileged background – she was born into slavery in Mississippi during the Civil War – but also how she learned to read, attended a Historically Black College, and developed an appreciation for the liberal arts. She offers thoughts on how educators should use Wells’ many public writings, diaries, and firsthand accounts of the horrific crimes of slavery, segregation, the Klan, Jim Crow, and lynching in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to help students recognize this nation’s history of racial violence. They also explore Wells’ work as a reformer during an era known for overt racism, as well as rapid industrialization, corrupt urban political machines, and suppression of women’s rights. The interview concludes with Professor Giddings reading from her Wells biography.

Story of the Week: Cara and Derrell hold a moment of silence for the victims of the Uvalde school shooting, and discuss what is (and is not) being done to address the hundreds of thousands of disaffected and distant kids across the country who are struggling with mental health issues, especially in the COVID era.

Guest:

Paula Giddings is Elizabeth A. Woodson 1922 Professor Emerita of Africana Studies at Smith College. Previously, Professor Giddings taught at Spelman College, where she was a United Negro Fund Distinguished Scholar; Douglass College/Rutgers University, as the Laurie Chair in Women’s Studies; and Princeton and Duke universities. She is the author of In Search of Sisterhood: Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority Movement; When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America; and, most recently, the biography of anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, Ida: A Sword Among Lions – Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching, which won The Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Biography and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award. She is a former book editor and journalist who has written extensively on international and national issues and has been published by The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Jeune Afrique (Paris), The Nation, and Sage: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women, among other publications. In 2017, Giddings was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Paula Giddings is Elizabeth A. Woodson 1922 Professor Emerita of Africana Studies at Smith College. Previously, Professor Giddings taught at Spelman College, where she was a United Negro Fund Distinguished Scholar; Douglass College/Rutgers University, as the Laurie Chair in Women’s Studies; and Princeton and Duke universities. She is the author of In Search of Sisterhood: Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority Movement; When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America; and, most recently, the biography of anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, Ida: A Sword Among Lions – Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching, which won The Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Biography and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award. She is a former book editor and journalist who has written extensively on international and national issues and has been published by The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Jeune Afrique (Paris), The Nation, and Sage: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women, among other publications. In 2017, Giddings was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The next episode will air on Weds., June 8th, with Chris Sinacola & David Ferreira, co-editors of Pioneer Institute’s new book, Hands-On Achievement: Massachusetts’s National Model Vocational-Technical Schools.

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode

Please excuse typos.

[00:00:00] Cara: Welcome to the learning curve listeners this week. Gerard is out, but I have the pleasure of being with my friend, friend of the show, Mr. Derrell Bradford, Derrell. How you doing? Thank

[00:00:37] Derrell: you for having me. It’s always, it’s a delightful to stand in for Gerard when he’s on one of his global jaunts.

[00:00:44] Yeah,

[00:00:46] Cara: Jaunting globally. Well, we appreciate you being here. So Derrell, you and I have decided today. I know I personally, wasn’t ready when we recorded last week show, but we’ve decided that instead of our usual format, going to go ahead and talk [00:01:00] about some pretty heavy topics we’ve got a guest, who’s going to talk about some pretty heavy topic and you and I have been, we’ve had people.

[00:01:08] The children, the community of Uvalde, Texas top of mind. and let’s start first by observing a moment of silence for those lost and those affected. And then we can wrap up.

[00:01:35] And that moment, probably feels really long. It felt long to me, Derrell, can only imagine what the moments have felt like For the families who have lost so much in these past couple of weeks. And just want to start off by saying think for a lot of us who are parents, probably the second or third things that comes to mind after something like this happens, which had happened.

[00:01:57] So. Far too often in this country,[00:02:00] is, should I tell my kids and how will my kids handle this and will I make my kids feel more unsafe than they already do? And so I want to share that a couple of days after it happened, I was in the car with my 12 year old daughter and I asked her. we haven’t even been listening to the radio in the car for this reason.

[00:02:20] And I asked her if she knew what had happened, knowing that there, she was going to hear something at school, et cetera. And you know, her response was both so mature and so frightening to me because she just looked right at me and she said, you know, mom, kids of my generation just understand that this is the country we live in.

[00:02:40] And so. I hate it and I am frightened by it and it enrages me, but I also just get that this is what we have to deal with.

[00:02:55] Derrell: Yeah. I can only imagine what it’s like to have to be a [00:03:00] parent. And, I think this through, you know, I was talking to a, colleague of mine who, was getting on a plane. He goes to a place and she was saying, my five-year-old is sort of noticing that all the hubs are a little bit tighter and a little bit longer.

[00:03:15] And my five-year-old no something is wrong. And obviously there’s something incredibly ephemeral, which many parents outside of the horrific events of last week deal with all the time, they send the kids to school and they don’t know whether or not they’re going to come home. And this is perhaps more widespread, a fear and like awfulness that American families deal with, but I really wouldn’t wish it on anybody.

[00:03:43] and it is truly, truly terrible. I know like two things, if I can throw two things out there, and one of them is going to sound cynical. , it’s not meant to be or clinical. It’s not, it’s not meant to be that either. You know, as a person who’s sort of [00:04:00] a creature of advocacy and policy change, you keep looking at these things and wondering why nothing happens.

[00:04:09] I can remember after the mass shooting in Parkland, the level of unrest, outrage, demonstration seemed like overwhelming and ubiquitous and. What like bump stocks got banned? I think books last got, bad, but, in the end it was just like, about all of that? Didn’t translate into more substantial policy change and that’s the kind of thing we sort of analyze all the time.

[00:04:39] It’s really important. and I not, no have a, have an answer for it, but I know somebody needs to have an answer for it. And then the second thing is just like, I forgot. Certainly a behavior that we wouldn’t sort of categorize as normal of all kinds has been on the rise. [00:05:00] And seemingly started to peak in, 2020, when we, as a nation made sort of a policy change that we.

[00:05:08] Weren’t going to be around one another for two years in the interest of everyone else’s safety. And full disclosure, I always say this, like I followed all the rules and spent two years in my house. The moment that people were talking about locking down schools, I was at the front of the line saying we should do it, but all of these policies have trade-offs and I fear that we have unleashed something.

[00:05:31] Atavistic and angry in the American psyche that is presenting itself in ways that nobody really wants to acknowledge fully or act on in a fashion commensurate with the expansive nature of it all. And the adults in, you know, um, in New York, like. What’s going on in the subways. This is pretty, you know, for instance is outrageous.

[00:05:55] , it’s almost like a bad movie. out of control it is. And[00:06:00] what has happened to what must be like thousands, if not more of disaffected high school kids who had their schooling and lives disrupted over the same period. was a policy choice and the trade-off and we got to live with that and an incredibly serious way for them and for us and for everybody.

[00:06:22] And I just want somebody to be an adult about that and acknowledge it and start talking about it in a genuine and meaningful way.

[00:06:28] Cara: thank you for that. I think, to your second point first about the unforeseen impacts of the pandemic. I mean, I remember listening to. Podcast with our now surgeon general actually pre pandemic when he was warning folks that loneliness is an epidemic in this country, right?

[00:06:46] The people are profoundly loneliness country. And I think that that plays a lot into what you’re saying and that, the pandemic. Exacerbated that, and, those of us who were locked down, you know, if you’re locked down alone, [00:07:00] you, might be lonely. but you might also be safe. You might also have the resources to keep yourself healthy and fed.

[00:07:07] and a lot of people in this country, many of them children were locked down in environments that absolutely weren’t safe for them. And weren’t healthy for them or the whomever they were in the home with. But it also, I think, reveals these fractures. Obviously the huge fractures in our society, which go much more to your first point, which I’m still, I think I said earlier, gone from like just sadness to a little bit of depression to just being so pissed off.

[00:07:36] But I feel like it’s, concerning because I go through that cycle every time and then life moves on and it probably shouldn’t. , but to get back to the idea of that, the kids are not all right here. It’s right. Our schools from good schools and many of them of all types are good schools. Provide centers of community, provide resources for [00:08:00] kids, socio-emotional mental health, whatever that is, to some extent, probably not enough.

[00:08:06] but that not only did the pandemic heightened, whatever. Dystopian feelings that kids are experiencing, blame it on whatever you want. Blame it on social media, blame it on set, blame it on 1,000,001 things, right. It probably doesn’t even matter at this point. It’s that too many of the adults. Who work with these kids in the system?

[00:08:25] don’t have I hate to talk about the resource question. I’m not usually wanting to say, oh, resources are gonna fix the problem, but just aren’t I can’t imagine being, for example, a school counselor, or even a teacher and being even emotionally. mean, I can barely deal with the emotional stuff with my own family, half the time, let alone understanding what these kids are going through, have been through and how they’re going to continue to deal with that and take it out on one another.

[00:08:51] And we have in this country for a very long time, we fight right about the language of how to support kids when she would call it SEL [00:09:00] no Canada like that, which we call at the end of the day. If we can’t understand. That people are not okay. And kids can’t learn. If they don’t feel safe, kids can’t learn.

[00:09:10] And that goes to bullying or mass shootings and they can’t, they can’t learn, they can’t be present. So I feel, yeah. And I am wondering though, as you know, I’m, more of a policy creature and less of an advocate security than you are. Is, the larger conversation, the very important conversation around the change that needs to happen, changes that have happened in places like Australia and Scotland after similar things have happened once not 27 times in one year.

[00:09:39] but then there’s also this conversation that I think you’re pushing at around. What do we do to support women? Okay.

[00:09:48] Derrell: Yeah, I was talking to my boss about this and it’s like, we’re education policy, experts for the most part, not, gun policy experts and I’ve been unwilling to step out of that lane because I, [00:10:00] take what I do seriously and I don’t, want to be sort of too.

[00:10:04] flick about what you prescribe from an area in which you don’t have a ton of expertise, but couple of things actually come to the surface and they are not merely sort of the glib take that kids are resilient that you found that, Valerie Strauss put famously in the Washington post.

[00:10:27] When talking about, school closings year ago, the first thing is that I can’t remember who said this, but it’s like very specifically the issue of, school shootings. , there’s a lot that happens to a child before they get to the school that we could intervene on. And I think it’s sort of important to think of.

[00:10:47] Series of opportunities that we have to intervene as something longer and more nuanced than just being there at the school house door or hardening that door. , and that’s the first thing. The second thing is [00:11:00] actually a little bit counterintuitive the move right now. I think this asylum move, which in many might be, you could look at it as practical, but you can also look at it as political to consolidate all of the.

[00:11:15] things needed to intervene for a kid who is stressed, unwell, , whatever you want to call it, like under the mental health umbrella, the push to consolidate all that in school to me is wildly mistaken, , and hugely detrimental. and here are my reasons for asserting it. One is that, you could say, oh, the last, like two years there.

[00:11:40] Like three and a half million teachers in America where there’s like 8 million of them. there’s 8 million of them. If you count all of the churches, retirees, mentors, and mentees coaches, docents, and every other person who stepped in to the lurch to help kids do [00:12:00] something with their learning. When the ritual of K-12 was disrupted, , as it was because of COVID and those people are a part of the.

[00:12:09] And they need, to be, we need to lean on that, right? The idea that we should. Recreate a paradigm that basically excluded all of them, is absolutely the wrong way. And if that means like, fun families, you know, or like give everybody a, mental health voucher or like a cop sports are free for the next two years or whatever it is.

[00:12:29] Like all of those things that help people build connections and help them find who they are and like mediating institutions. So they are less lonely. so more people can see them and support. we absolutely have to invest in that. That’s the one thing, the second thing. And I’m sort of a little tongue in cheek, but not really is it.

[00:12:47] We just have to realize what schools are good at and what they aren’t. And the primary job that we’ve been asking American schools to do. And some of them do it really well over the last, [00:13:00] like, I don’t know. My lifetime has been to turn out literate, numerate kids. Who could go on and be rational participants in our democracy.

[00:13:10] So, you know, so we’re free from tyranny, right? And so people can live out our ideals. And in 20 19 1 in five black fourth graders in this country, tested at, or above proficient on that. And that was before the unrest, the crisis, the friction of the last two years, the idea that now we want schools to also be centers of all of this other expertise is ludicrous.

[00:13:40] When you think about the fact that the core job we need done for many American kids has not been done well. I would just throw those two approaches out there as any approach for. what I think is like right now, I think we’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg. Like, I think to your point, you said it, the [00:14:00] kids are not all right.

[00:14:01] That is expressing itself in lots of different ways. Like you can look the New York times and high school principals are saying, freshmen showing up back in like sixth graders. I was talking to mark, my boss and he was, reading a thing was counselor.

[00:14:14] So like kids are late or absent, 88 to a hundred times over the last year. Right. And nobody seems, nobody seems to want to do anything about it. It’s just all outrageous. And it’s a serious problem with. imagine our way out of it. It’s going to take serious people who want to get along and bring people together and do what’s right for the.

[00:14:35] Yeah, and

[00:14:36] Cara: I would, agree. And I would add to that, that I think that, the kids are not all right. And they’re being led to slip through the cracks by not showing up to school or always being later because so many the adults aren’t all right. Either. Right. Just people feeling like I can’t, there’s only so much I can do.

[00:14:53] There’s only so much I can give. I know, personally, I just had a conversation with a friend yesterday. I have [00:15:00] stopped. Like I’ve always prided myself on being a person who read the news and listen to the news and I do all the right things. Right. I can’t do it anymore because, you know, I don’t find a moment of joy.

[00:15:08] There’s still good stuff in this world. Right. But it’s a scary, depressing place. If you spend your time listening to that and. I would agree with you too. I think, I remember as far back, as long ago in grad school, having this debate over can schools be everything to everyone, and I agree with you.

[00:15:23] They cannot, agree with you that if we can barely do the core function of making sure that all kids can read, then we’re in a bad place, but we’ve also been so not innovative, right? For the most part. How do you like there’s this great school here in the Boston area called Codman academy. it’s cold located in a health center that is like everything to that community, that health center.

[00:15:49] If you ask anybody in Codman square, like what defines COVID square, I guarantee you that many people are gonna tell you about the health center. And they’re going to say, and every family that walks through that door, they might not want. [00:16:00] They might not think need it. They get assigned somebody who’s there to be a resource to the family.

[00:16:06] Whether it’s, you need somebody to talk to, you need to make sure that your blood pressure’s in check, like all of the things. And therefore they’re there. Not just for the kids. They’re there for the parents. They’re there for the siblings, Thinking through to your point, how you leverage civil society in the ways that we used to at some point, right?

[00:16:27] We weren’t bowling alone, is really important. And I think our kids and our families are absolutely feeling that. And one of the big concerns I have is when you talk about, yeah, I would be for how do you get resources into the hands of people that need them, but, people have mean. there observant might be able to look at their kids in purchase the therapist.

[00:16:48] That’s $500 a session and not covered by insurance and all of these things. So we know who’s getting left out of the equation. We know who doesn’t have the access that they need. And it’s just quite frankly, [00:17:00] it’s not a priority in this country. And I think part of my anger stems from the fact that we can’t seem to, gosh, darn figure out how to make.

[00:17:10] A priority, even though when I think so many of us are feeling the same thing and walking around with a bright smile on our face and doing the good work and doing our jobs in the inside, sometimes we’re falling apart.

[00:17:21] Derrell: Yeah. agree. And I, just want to want to say again, it’s like, while it is always, a joy to do the show with you, I’m glad we had a chance to.

[00:17:33] I acknowledged the tragedy of these 19 young people and their families and to educators that lost their lives because of it.

[00:17:41] Cara: Yeah. Yeah. Thank you for that. I agree. And maybe who knows you and I work in very similar circles, maybe this will become more of a priority for the kind of work that we all do together.

[00:17:53] And, new era of, not just education reform, but just supporting families and students. So. [00:18:00] Yeah, I would like that too. Let’s see. New project coming up right after this derail. We’re going to be speaking with professor Paula Giddings and she is the Elizabeth a Woodson professor, emerita of Africana studies at Smith college and the author of Ida, a sword among lions, Ida B Wells in the campaign against lynching.

[00:18:21] So learning curve listeners, please come back to us, right.

[00:18:52] Learning curve listeners, please help me welcome Paula Giddings. She is the Elizabeth a Woodson 1922 professor emerita of [00:19:00] Africana studies at Smith college. Previously, professor Giddings taught at Spelman college where she was a United Negro fund, distinguished scholar Douglas college Rutgers university as the Lori chair in women’s.

[00:19:12] And Princeton and duke universities. She is the author of in search of sisterhood, Delta, Sigma, theta, and the challenge of the black sorority movement when and where I enter the impact of black women on race and sex in America. And most recently the biography of anti-lynching activists, AWS. Ida a sword among lions, Ida B Wells and the campaign against lynching, which won the Los Angeles times book prize for biography and was a finalist for the national book critics circle award.

[00:19:41] She’s a former book editor and journalist who has written extensively on international and national issues and has been published by the Washington post, the New York times, the Philadelphia Inquirer Juna freak and Paris and the nation and Sage, a scholarly journal on black women among other publications.

[00:19:59] In [00:20:00] 2017 Giddings was elected to the American academy of arts and sciences. Professor Paula getting thank you so much for being with us today. And I am going to invite my friend Darell to take it from here.

[00:20:12] Paula: Thank you. Yeah.

[00:20:13] Derrell: Thank you for being with us professor Giddings, but because I am the king of understatement, I’ll start with the.

[00:20:20] You have an impressive career in academia and journalism,

[00:20:27] Paula: who was that woman you were talking about

[00:20:34] Derrell: previously? You said that, uh, I think this is very important. Given the moment you said you think America runs on rage and courage, would you, , share with our listeners some of your own story and how like historic events, like the civil rights movement and freedom rides shaped your life and thinking about the country?

[00:20:53] Paula: Indeed. Well, thank you for having me looking forward to this, talking to you and well, I’m [00:21:00] a child of this civil rights movement. I grew up in the period of the civil rights movement and, Incidents and experiences that are so , and so defining may sort of stay with you for most of your life.

[00:21:14] And this was true of the freedom rides that, for me, that took place in 1962. I was 15 years old at the time when I saw this. And when I saw the freedom rides on television, And as those of you who may not remember, or who don’t know very much about the freedom rides these were a ride, this was the idea of, civil rights workers to take buses from the north and go south, to, integrate waiting rooms, et cetera, in the.

[00:21:47] and, the, , ride started off, they were very dramatic and there was some success, but there was some of the rides. And I remember when one of the buses hit Anniston, Alabama. other places [00:22:00] there was such violence. Buses were stopped.

[00:22:03] People were taken off the buses, some of the buses were bombed. People were beaten. it was the first time I saw such rage. That’s the idea of that rage came from. but, instead of being the. Especially the young people who are, involved in the rides said they just would not stop.

[00:22:24] They were going to continue to ride. They were not going to be defeated. And that was the courage that I saw. And then I started thinking about it as a teenager. I mean, what is this thing called race that brings out both that rage and that courage. And I think that’s really been my defining mission, for my writing, my professional life in particular, I’ve always searching for that answer.

[00:22:49] Derrell: that’s wonderfully said and probably pretty good segue to , my next question. your biography. I’ve spent some time learning about Ida B Wells down, but,[00:23:00] you were Ida B Wells, sword among lions, , Ida B Wells in the campaign against lynching, is your definitive volume on the often underappreciated, wildly unsung figure of IDB Wells in American.

[00:23:15] Could you give us brief overview of her life and why she’s so vitally important as just like a person, as a figure for school children and for the general public to just know significantly more about than they do.

[00:23:29] Paula: Yes. It’s very dangerous to ask biographers flush.

[00:23:35] I will do my best to be weld. What drew me to her. as a figure was her current. If you want to talk about courage in the face of rage, because she started the first anti-lynching campaign, in the country in 1892 from the south, from Memphis, Tennessee. And she had such courage, not just physical courage, dural, [00:24:00] but also a kind of social courage in which he had a conviction about stopping lynching and understanding the real reasons for.

[00:24:10] And she followed that conviction, even though, it went against, , so many of the mores and rules of the society that time, you know, we’re talking about Victorian period when no one talked about certain kinds of things when women, didn’t write about politics or, speak out loud about things.

[00:24:29] or certainly he didn’t, as she. Became an investigative journalist traveling alone often in the south investigating lynchings. This is in the 1890s century. I was

[00:24:42] Derrell: stunned by this, not just the, to your point about the ability to sort of bring this career as an, investigative journalist into existence.

[00:24:51] But the fact that she did this sort of alone in this, in the face of sort of all of this. the threat of physical violence, enormous [00:25:00] physical violence, right. And obviously being black woman in the south, trying to report on this, obviously racial violence is right there too. It was really astounding.

[00:25:12] Paula: Yes, indeed. I think it’s wonderful for students to have models of, people who do this guy, who had that kind of courage and that courage of conviction. Which was so important, quick overview, she was born into, I like to say on the cusp of slavery in she grows up in the reconstruction period, which is a great period of course, hope and change to borrow a phrase.

[00:25:44] she, comes of age. Though in the post reconstruction period, which has been characterized by numbers of historians as, the Nader in our history because of the disenfranchisement of African-Americans of the [00:26:00] increase in violence. and certainly is what stands out is the increase of lynching, of black, men.

[00:26:09] The rationale for this lynching, because remember you had to have a rationale because this is extra judicial fraud. This is outside of the law. So there had to be a rationale that justified such an act. And that thing was the, accusation that black men in particular, were raping white, this had sort of broken out, in this period of time.

[00:26:35] And unfortunately it was affirmed by much else that was going on in this society, including the sciences. This is a period of the emergence of the social science. And even those, , scholars in the Ivy league schools, talked about the fact that blacks were regressing, because there were no longer under the tutelage of slavery and that they’d [00:27:00] become vicious and more and more primitive, and therefore lascivious, and criminally prone.

[00:27:06] so this was the justification and lynchings became, they became even not only more numerous in the late 19th century, but also more vicious in 1892. And Wells is 30 years old, a friend of hers in Memphis, Tennessee, by the name of Thomas Moss is. And to shorthand it. The only crime Thomas Moss, ever committed was to, , out-compete a white, , proprietor Thomas Moss was a co-owner of a grocery store, , that competed with that number or the white.

[00:27:41] Incidents that happened. Right. And he is lynched because of that. And well, begins to understand, that lynching doesn’t have anything to do really with rape, but it really an effort to keep blacks down in a period, , where there’s [00:28:00] industrialization, where there’s a great deal of economic competition.

[00:28:02] and were blacks were doing so well, they really were emerging in these communities, and beginning to thrive. And so when she understands that lynching is really at the heart of big, because it is mentioning, is within the context of all these terrible stereotypes around black people that she decides that lynching is the thing that, when she unpacks it, it makes people understand what’s really going on.

[00:28:30] she will helped deliberate sort of ideas around black people in there for, you know, facilitate equality later. But very, very quickly. She is exiled from Memphis for anti-lynching editorials. her office is destroyed. , she goes to New York for awhile and finally settles and marries and continues her reforms, in Chicago.

[00:28:53] And we can, if you want to ask him about that, I can tell you more about that. She said it just the epitome of [00:29:00] a great reformer around women’s suffrage, , around, creating a settlement house. for blacks and they’re in Chicago, she’s a co-founder of the NAACP.

[00:29:10] Derrell: Wow. yeah, my, research, her economic insights on lynching were also incredibly powerful.

[00:29:17] absolutely. last question from me. so Ida B Wells was born the, in the slavery, as you sorta noted earlier, to taught herself, to read, attended a historically black college, and was also widely read like a Shakespeare Dickens, you know, Bronte. would you talk about how this kind of.

[00:29:38] Liberal arts learning help define her life and her writings and her ideals, as well as like what we can draw from who she became from how she, became

[00:29:50] Paula: educated. Yes. she is a great example of the power of reading. , she read everything that she could get her hands on, , and lots of women’s literature [00:30:00] as you’ve just, , , noted.

[00:30:01] And when you think about what she was reading, , many of those carrots there’s, Alcott and Bronte, number of them were young girls. Who just had a lot of challenges in their lives and had some tragedies in their lives they overcame it. A number of them are orphans. Like she either was orphaned at the age of 16 because of the yellow fever epidemic.

[00:30:26] some of these girls, these characters were, offered and as well, but they were impounded. was particularly struck, with a phrase from middle Jo in little women when little Joe is determined to leave the family and go to the city, become a great writer and write things that people will always remember help to change the world.

[00:30:49] That was her aspiration. and in terms of even Shakespeare, either, love the theater and she even, played lady Macbeth once,[00:31:00] and I think from, so when I saw the comments that she should probably, you know, kept her day job. but if you think about lady Macbeth, which asks the gods on sex me so I can do what I have to do.

[00:31:15] you can see where this could be also affirmation and inspiration, for her. So she was also a lonely young woman, and she had great joy in the world that literature.

[00:31:31] And of learning also help you write your great storytellers and she became one as well.

[00:31:37] Cara: Hello professor getting, thank you so much for being with us today. have to say I’m staring. I always have a copy of little women.

[00:31:46] Paula: Love the dead end,

[00:31:48] Cara: always at the coffee table here at my office because it’s one of the things.

[00:31:52] Paula: I could go back to get it, to get it

[00:31:53] Cara: again. Now, compelled to follow up on a question, I think is related to one that [00:32:00] Derrell asked. And I want to preface this by saying that, I guess about three years ago, pre pandemic, I had the great fortune in the organization that I work for, took every single employee on a retreat, that legacy museum and.

[00:32:13] of the many, many ways in which that plays left an impression on me. One of the biggest was that, I’m a child of the 1980s. I thought I went to pretty good schools and oil boy being there, making me realize I learned nothing about the history of this country. it was a rude awakening, , for me in many, many levels about my.

[00:32:30] school education and myself education. and so the question I want to put to you is when we think about folks like Ida B Wells and her works, including not only her public writings, but her diaries and her , experiences witnessing the events That shaped our history in such horrific ways.

[00:32:50] how can reading these things help today’s students understand the history of race in lynching in America?

[00:32:58] Paula: I know Wells [00:33:00] understood. you have to not just write history, but write a narrative, a story about what was really going on. And that was one of the power she had as a, journalist.

[00:33:11] one of the things , she made sure to do because she also consider herself. she was very upset for example, that, a number of victims mentioned, you know, that they were, that their names were never known or that it, they don’t want to sound too gruesome, but often families were afraid to even , retrieve the bodies because they.

[00:33:33] penalized punished. and so she always made sure when she did her investigative reporting to talk about who those people were and to name names, , and. to give them a place, in history and I think that’s a lesson will the humanity of what she was doing, not just an ideological or a political, mission, which of course it was those two, but a [00:34:00] humane mission, as well.

[00:34:02] I’ll tell you a very quick story. I was on a panel, it was a panel on the Ida B Wells with a number of others who had worked on her. And, I was on the day is, and a woman comes up to me before the panel starts and takes my hand and she said, we learned what happened to my great grandfather by reading your book.

[00:34:24] I had quoted Ida Wells writing about, , some men who had been lynched outside of Memphis, Tennessee. And this woman’s great-grandfather who was one of those. She said he had disappeared. No one knew what happened to. So, right. Flabbergasted, right. but very, very moved. And I said, well, that’s why I’m doing this right.

[00:34:48] I mean, that’s very important. her diary is very interesting. and what I got alphabet was, well, first of all, You read the diary? [00:35:00] it is, as far as we know, the only kind of eyewitness to, the community of a place like Memphis, the Memphis, in the 1880s and in this.

[00:35:12] And you, read about all the, daily life than what people were doing, and even what people were wearing, either Wells with the clothes horse who spent too much money for clothes, which I loved. I mean, she’s very, I love this. and in other ways as well, uh, so, you get that sense, but you know, the greatest gifts that diary was for me.

[00:35:34] Was that because of her experiences of being orphaned and sort of being taken advantage of in the community, which is a whole nother story. , she was a very angry person, but she was also self-reflective and you see all this in the diary and she understood that if she didn’t get a hold of her anger, that it would destroy.

[00:35:57] And so you can see in this diary, her [00:36:00] efforts to reform herself first, and it’s excruciating, but she does it. there are psychological profiles, which showed that lots of leaders. Or really people who are because leaders, when you think about by definition, you know, are assertive and aggressive.

[00:36:18] And, and at the root of aggression is anger. but the best leaders are those who are able to transform the energy, that negative energy into positive energy. And in her case into reform, you can actually trace this in the diet. a

[00:36:35] Cara: fascinating observation. I have to say we’ve previously had a guest on this show , who made the point that, some of the most, whether they’re dynamic or popular or greatest, depending on how you find that leaders have been actors.

[00:36:51] but this notion of how do you transform that? I’ll also take with me from what you said, this idea that she had this compulsion to help name victims, [00:37:00] which I personally took away from my trip to the legacy museum, but I think is very relevant to some of the challenges Derrelle and I were discussing at the top of this hour, before we brought you on about, challenges we’re facing in this country, I would love to ask you one last question and you, began to talk about this and we put a little bit of a pin in it and I’d like to come back.

[00:37:18] So can you talk more about Wells’s work as a progressive reformer, a black, progressive reformer in thinker during this era? her gender alone. Right. But an era of overt racism and then you couple with that industrialization and corrupt urban political machines. Right. So tell us a little bit more about that and what, lessons would you have a straw?

[00:37:43] Paula: a great example. Let me explain it through an example. either Wells, Actually founded the first black women’s suffrage organization in Chicago. in 19 12, 19. And the [00:38:00] reasons why she did of course, we know that there was, lots of momentum towards suffrage and towards the 19th amendment at that period.

[00:38:09] But there was also a passage of legislation, in Illinois where women could vote in municipal elections. as a result of the progressive party winning a number of offices in Illinois. So she was preparing, black women to mobilize for this. And once that legislation was passed, and this is exactly what she did was to mobilize black women.

[00:38:33] Why? Yes, for the boat, but not just for the boat sake. There was, the black committee. and particularly the second ward, which is where all blacks coming from, the migration south were shoveled, right. was actually run by, , the, Chicago political machine. That was correct. paid people off so they could maintain their power, but at the same time, [00:39:00] the second ward and that area was deteriorating because no one was really paying attention, to it.

[00:39:05] And the quality of life of blacks was, declining. So her idea was because the men couldn’t be trusted so much. that’s mobilized. And let’s mobilize behind an independent candidate.

[00:39:20] So she challenges , the, she is so, so, and she was very, very, , successful, as a result, oh, also let me not forget that there was no black representation, even with a great, with a majority black population in that, area. So it because of her and solve a long story to unwind. because of her and because of what women are able to do, the machine had to at least give.

[00:39:51] had the, have emerged a black candidate to be a, an alderman, which is like a city Councilman and well, and her [00:40:00] people got behind him, ask her to priest who wins the election and becomes the first black older man, in Chicago. And later he will become the first black, to be in the house of representatives since reconstruct.

[00:40:14] what she did was she developed more than just one person. She developed a constituency, for progressive, reform. And ever since after her mobilization, people always had to come to the women, to make sure to get their support. And they made the difference in a number of elections.

[00:40:33] Derrell: I’m listening to all this, and I’m just saying. What have I done with my life?

[00:40:39] Paula: I’m listening to this

[00:40:40] Cara: and I’m saying, because the pen can’t be trusted, let’s mobilize the

[00:40:44] Derrell: women met. There are many lessons that many lessons,

[00:40:54] Cara: we’ve been talking so much about the writings of Ida B Wells, but we would love to hear some of your own. So,[00:41:00] would you read us a passage from your.

[00:41:02] Paula: will, this is from a chapter called the truth about lynching. What I, the Wells wrote after being exiled from Memphis, she was invited to write for an important black newspaper in New York when New York age, the column was called.

[00:41:17] The truth about lynching, which really becomes the first study of lynching. so I, tried to characterize the impact and the meaning of that work. And as it related to her, And this is also back to particularly social courage as well, physical courage in order for Wells to follow the logic of mentioning and to its ultimate conclusion, she herself had, had to take a deliberate flight from the radical innocence that was at the heart of Victorian thought.

[00:41:53] Is with no pleasure. I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed. She told her readers either [00:42:00] replaced the language of gentility with reality and dispense with the quote false delicacy of the quote unspeakable crime, which was lynching. She was one of the few women reformers who actually used the word rape and had learned to do so without a problem.

[00:42:20] Well, it’s understood the radical implications of your message and was prepared to endure the consequences. Even if, as she said, quote, the heavens might fall, but she had made up her mind that her campaign, wherever it took her, was her calling and that she would see it.

[00:42:39] I just crusade to tell the truth about lynching gave her the means to reorder the world and her and the racist place within it. Once the famed yourself. Now she could expose that lies the Sully, the races may. Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned [00:43:00] against, than sending wrote Wells who had found the vehicle of her destiny.

[00:43:05] And it seems to have fallen on the, to do so and quote. It’s

[00:43:11] Cara: amazing. Seems to have fallen on me. And if, even if the heavens may fall is quite a mantle to bear

[00:43:17] Paula: and the heavens didn’t fall. Let me tell you, she was like, know what they talk about? I guess it’s sort of sexist, but just talking about the little old lady driving down the middle of the street and everybody’s everything crashes around the.

[00:43:35] Cara: Amazing. Well, professor Paula Giddings. Thank you so much for your time today. This has been truly enlightening.

[00:43:42] Paula: Well, thank you. Thank you for your wonderful questions as well. please

[00:43:46] Cara: take care. I know our listeners will enjoy

[00:43:50] Paula: thank you so much.

[00:43:51] Cara: [00:44:00] First of all, thank you to Derrell for being with us today and for the great conversation, sad conversation, frustrating conversation, but I think while worth having. And, we always appreciate you coming on the show and being such a good friend of the show next week, we’re going to be speaking with Chris Sinacola and David Ferreira, and they co-editors of Pioneer’s new book.

[00:44:51] Hands-on achievement. Massachusetts is national model of vocational technical schools. Darell, anything you want to share before we sign off?

[00:44:59] Derrell: [00:45:00] No. I,, can think of lots of places I’d like to be, virtually, but none of them better than being with you and the pioneer Institute and learning curve podcasts to thank you.

[00:45:11]: We

[00:45:11] Cara: love it. I’ve got a big smile on my face right now. I needed that. Thank you. All right. We’ll talk soon. All right.

[00:45:16] Derrell: Cool.

Recent Episodes

Stanford’s Arnold Rampersad on Jackie Robinson

Pulitzer Winner Kai Bird on Robert Oppenheimer & the Atomic Bomb

Georgetown’s Dr. Marguerite Roza on Federal ESSER Funds & the Fiscal Cliff

Harlow Giles Unger on Patrick Henry & American Liberty

Prof. Joel Richard Paul on Daniel Webster, U.S. Senate, & “Liberty and Union”

Steven Wilson on Charter Public Schools

Sheldon Novick on Henry James, American Women, & Gilded-Age Fiction

USAF Academy’s Jeanne Heidler on Henry Clay & Congressional Statesmanship

https://pioneerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/TLC-Shiloni-05292024-767x432-1.png

432

767

Editorial Staff

https://pioneerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/logo_440x96.png

Editorial Staff2024-05-29 16:14:072024-05-29 16:27:34Israeli Harvard Student Maya Shiloni on Campus Antisemitism

https://pioneerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/TLC-Shiloni-05292024-767x432-1.png

432

767

Editorial Staff

https://pioneerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/logo_440x96.png

Editorial Staff2024-05-29 16:14:072024-05-29 16:27:34Israeli Harvard Student Maya Shiloni on Campus Antisemitism

Kimberly Steadman of Edward Brooke on Boston’s Charter School Sector

Cheryl Brown Henderson on the 70th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education