Lauren Redniss on Marie Curie, STEM, & Women’s History

/0 Comments/in Featured, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffGuest

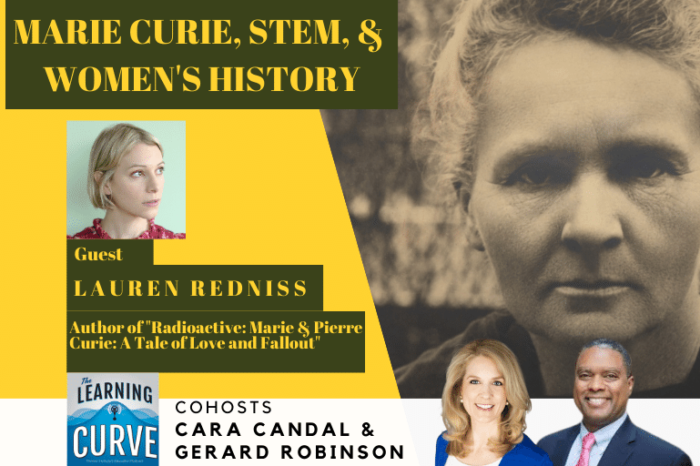

Lauren Redniss is the author of several works of visual nonfiction and the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.” Her book Thunder & Lightning: Weather Past, Present, Future won the 2016 PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award. Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout was a finalist for the National Book Award, and the basis for the 2019 major motion picture, Radioactive. She has been a Guggenheim fellow, a fellow at the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars & Writers, the New America Foundation, and Artist-in-Residence at the American Museum of Natural History. She teaches at the Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a transcript here:

[00:00:33] Hello, listeners, welcome back to another fantastic show for the Learning Curve. I’m Gerard Robinson, coming to you from beautiful Charlottesville, Virginia. Of course, it’s really tough to do anything great, anything wonderful, anything good, without having my co-host with me. Cara, how are you?

[00:00:52]

Cara: I’m great. I’m gonna record that. I will record that—I don’t need to record, it’s recorded. I’m gonna play it at the dinner table for my children as they scream at me about like, why did you make this for dinner? Why do I have to go to bed? Things like that. I was gonna say, because I’m—Thank you very much Mr. Robinson. I appreciate it. I’m not coming to you from beautiful Charlottesville, but from rather cold Boston, still beautiful. What’s in your mind in the world of learning, news for our listeners?

Gerard: Well, mine is from the great state of Texas, from Houston in particular. And they say that everything in Texas is big, but this story is going to be big. And depending upon what side of the fence you sit on, you’ll think it’s big, good or big, bad. The Houston Independent School District has 200,000 students. It is the largest system in Texas, one of the largest systems in the country. Former Secretary of Education Rod Paige was the superintendent of Houston when he was selected to become U.S. Secretary of Education.

Well, there is conversation at the State House, whether or not they should take over the entire public school district of Houston. And the reason for doing so is what broadly falls in the literature as academic bankruptcy, even though we don’t utilize that term. Now, there are a lot of academic challenges in Houston, whether it’s the dropout rate, the racial achievement, the number of students who are proficient based upon NAEP or even state scores and a whole host of things. And so those of you who are familiar with state takeovers, this is a messy process. But you know what, when you start talking about it, even before the final yes is put on a document a lot of players.

[00:02:43] So Superintendent Millard House II said that uncertainty looms right now. And when I checked the news today before our show right now, the possible takeover is gonna be Monday. It was actually scheduled to take place this week. So we’ll see. And the superintendent said, well, while the lawmakers ar etrying to figure out what to do he made note that in the last 19 months, Houston School district, in fact, made great strides by reducing the number of campuses that received a D or F grade from 50 to 10.

So that marks movement. The superintendent also talked about the work that his teachers and central office administrators are doing to try to close the achievement gap. Now, that’s the superintendent. There are also community members who said, Hey, we don’t think this is a good idea. In fact, the convention center, there were chances of, Hey, hey, ho, ho, TEA has got to go. This the Texas Education Association. It’s their Board of Education. And the Mayor of Houston, Sylvester Turner, State Representative Jarvis Johnson and others were present and said, listen, we’ve got challenges, but keep your hands off Houston. The takeover’s not gonna do anything.

[00:03:56] Well, I’ve got some experience in this both academically based and practically. I worked for at that time it was superintendent Arlene Ackerman in D.C. Public Schools in the late 1990s when in fact, DC had been taken over by Congress and D.C. was Congress. In Cleveland, it was the state. And in Detroit it was also the state with the mayor and just took a look at that. So, some of the people who were interviewed for the story including educators, said that this is a slap in the face. One teacher, teacher Murray said that being an educator in Houston, this is a slap in the face for them to even want to talk about taking over school when we work so hard, and we often do so less resources. So, teachers traditionally have not been a big fan of it. Many parents have not been a big fan. In fact, questions about are they doing this? Is because this is a Democratic stronghold, that this is payback for some political losses and wins.

[00:04:53] Some say possibly some say no and naturally be in Houston, a place where the majority of the students are students of color question. Systemic racism, but this charge isn’t just one that’s new for Houston. If you look at the takeover of New York City, of Cleveland, of Washington, D.C., even Jersey City, which was the first major takeover, which occurred in 1989, concerns about racism, partisanship were a part of the play.

[00:05:20] If you look at this through the lens of academics, you know what? Takeovers have mixed results on one side. Finances have been stronger. Streamlining the process of management has been great. And in instances where you’ve replaced the elected board with either appointed people or by the governor or a, I guess, a hybrid model between governor and mayor, you’ve gotten people who would say, I had never run for public officer, school board in particular.

[00:05:45] But you know what? If I can help my school system, I’ll join. That’s been some great things on that side of this. On the academic side. It’s mixed. You know, some grades have improved in math and science in other cities. We didn’t see a great change in, in some of the school systems in New Jersey, you found a reverse. So, I’m gonna watch this in part because if in fact it takes place, it’ll be the first big city school district in the Deep South to be taken over. All the cities I’ve mentioned before, D.C. is the south, but it—all the cities I mentioned before, but congressionals, that’s a different story, but the question is if academic bankruptcy was the reason why states should have taken over school systems, New Orleans, maybe even Atlanta at one point, Jackson, we can name a slew of Southern cities that could have been taken over. But the reason you could not was because of the Voting Rights Act and with changes in the Supreme Court and with some rulings in the last 15 years, that is no longer an obstacle to getting there.

In fact, speaking about the court now in with this, when the legislature thought about taking over Houston in 2019, Houston actually sued, and in 2020 there was a Travis County judge halted the plans to take over. Well, the case eventually reached the Supreme Court where the agency’s lawyers last [00:07:00] year argued that a 2022 law, which written to effect after the case was taken to court, actually allows the state to take over well, the state Supreme Court threw out the injunction this January, a couple of months ago, clearing the path for the takeover. So Houston’s gonna be a part of a major conversation because you have education, you have race, you have law, partisanship, and politics. What are your thoughts?

[00:07:30]

Cara: We have been talking about this for decades, mumber one. About a year ago this time we were talking about potential takeover of the Boston Public Schools. And you’re right, in every single case, it’s politics, it’s race, it’s what the community wants, et cetera. And I, want to touch on something that you said, which I’ve said before, which we all say is that, these state takeovers have quote unquote mixed results as do school turnarounds. They have mixed results, et cetera, et cetera. My question for all of us to consider is what are the results when you do nothing? What are the results when you just let the status quo be? When you say, okay, teachers, we understand like the struggle is real. So we’re just gonna, what? Let things keep going and kids won’t learn?

So I get to this point where I think, so if there are no answers, we need to probably start looking for one instead of going back to the same old thing. The one good thing about, in my mind, I’m sure lots of people will disagree with this—the one thing about a state takeover is as a taxpayer, as a parent, as somebody who cares about kids, I want to know where does the buck stop? Because when it’s a school district, whether it’s Houston ISD, or it’s Chelsea Public Schools or whatever it is, when it’s a school district, they can always say, well, we’re under-resourced, we don’t have enough people, we don’t have enough of this.

[00:08:53] It’s not my fault. Right? So whose fault is it when the state takes over schools, the buck stops with the state and we can point to the state and. Hey, we need some transparency. We need some accountability. Show us what’s going on. Can the state go in and say, all right, here are some changes we’re gonna make.

[00:09:12] Maybe we will give you more resources, but we’re gonna control where they go. Maybe we’re gonna say, you have to use these particular high-quality instructional materials because the ones that you’re using that you think are good, obviously aren’t doing anything good for children. So, it’s a real struggle to understand, you know, the question around, is this right? Will it work? I don’t know if that’s the right question anymore. I think to me it’s more of a question of accountability and what are we doing for kids because neither model seems to be doing much for kids, but at the end of the day, the status quo to my mind is pretty much unacceptable, at least when you try and change the power structure, the accountability structure.

[00:09:54] Somebody saying, okay, I care it’s time to move forward, but I don’t know, Gerard, maybe you and I need to just take a hiatus, do some research on this, and come up with the magic bullet solution to what happens to help make these schools better. One of those things could be giving families different choices, of course, as Rod Paige knew well. He was the secretary when No Child Left Behind. Attempted to do that. And, and unfortunately it didn’t work very well given the vested interests that be. But I agree with you. This is a story to watch. It’s becoming sort of a tale as old as time will be really interesting to see if it happens in that incredibly large school district.

[00:10:31] Yeah. Texas is um, there’s always so. here’s a gauntlet thrown, it’s only second to Florida in terms of being in the news all the time, right? So, I don’t know, but thanks for that story of the week, Gerard. I mentioned choice. I mentioned giving parents more choice as, one avenue to at least in the near term, helping kids who are in situations where they’re not being served well, find a different situation. And choice is, choice is always on our minds. Gerard, I got to tell you, it has been on my mind a lot. And not, always for the best of reasons. So I know, and I think our listeners know well, your history, having worked with Dr. Howard Fuller, who’s been a guest on this show, I mean, been in Milwaukee in the beginning when the private school choice movement really took off. And that was a time when the people who were pushing for choice were folks who were saying Too many kids do not have access, they can’t afford to, for example, pay for tuition to get them out of a public school system that is not working for them, and so we’re going to come up with different mechanisms. At the time it was vouchers, it evolved into tax credit, scholarships. And today of course ESAs, you, you edited a book, that really brought around this idea that we could use education savings accounts or accounts that parents jointly manage with the state to sort of curate an educational experience for their kid.

[00:11:52] Well, if two years ago we were saying it was the year of choice legislatures are all over choice again this year. And of course, many of them happen to be in Republican strongholds. So, we already know, we’ve talked about Arizona going universal, Iowa is there. Florida is on its way now, of course, I’m push that Florida’s an exception. And then we’ve got Arkansas, I have to say—although I would probably differ with her on some thingsz—One has to commend. Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders for what is a gigantic and important education reform package that she’s put forward. And I have to say some of it with the help of some of my wonderful colleagues.

[00:12:30] And in that Arkansas package, an ESA is on the horizon. So, the article I’m looking at is in Forbes by Patrick Gleason, and it’s entitled School choice advocates have continued success in 2023 after noticing major victories in 2022. And it really, it just goes on to explain where all these victories are coming from.

[00:12:51] It notes as it should, that, although this is happening in Republican states, that doesn’t mean that all Republicans love school choice. School choice, ESA programs, voucher programs and the like tend to be a difficult sell with rural Republicans in particular who see it as a threat to their to their systems. Kind of similar to what you were talking about in the large urban district in Texas that we were just discussing. Even Texas is considering an ESA. Now, all of this, Gerard, I think is good, but I want to put one thing on the table and I really want your opinion on it. Some of these new universal ESAs, and this is just my opinion, Gerard. there’s one camp that says we need to blow it up. We need to blow up the system. I understand that, but the policy wonk in me says that it’s not always realistic. That policy making is, I think it was Lindblom called it the, a process of muddling through.

[00:13:42] Now I’m gonna point for a minute to the state of Florida where they’ve had meaningful school choice reforms since you were there. It’s been some 20 plus years. Right. And they have over time, slowly ramped up access to those programs. Meaning they started by saying, we are going to give the most options, the most choice, to those who have the least in terms of income, so those who cannot afford it, it’s going to be a means-tested program or for students with special needs, and we will ramp up these choices over time.

[00:14:10] Now, Florida will get to universal, but Florida’s already in a situation where those who aren’t able to afford private school tuition, for example, are going to get the scholarships first. Now, some of these other states, Gerard, they’re not structured that way, and this is what I think it’s not going to be the case, that those who have the least will get first preference into these programs, in part because even if we say something’s universal, there’s always some sort of cap on programs. Even if a state says we’re not gonna cap the number of students that can apply, there’s often what I would refer to as a supply side cap. So, if you just say, Hey, in a given state everybody gets access and there aren’t enough private providers, meaning private schools or other providers that parents can use with government money to provide education for their students, then you’re in a position where the people who are already in are going to have the most, right?

[00:15:03] So, this worries me quite a bit and one of the things that I Would encourage us, those of us who are fierce advocates for choice and who want to see the system change, is to first think about what the setup, what the layup, if you will, needs to look like to create really strong school choice programs.

[00:15:21] And I think it starts with thinking about is our funding mechanisms contrived so that money follows actual kids so that they can take it. So, if I have a student if I am the parent of a student with special needs who gets more money from her district, would that money—actually not federal money, of course—but would that money follow me to my new private school so that I’m getting the sort of the same amount I am due, or is it going to be a lesser amount?

[00:15:46] The same would go for low-income students who receive in their states, would that money follow them to their school or is it going to be a flat amount for everyone? And in the context of some of these choice programs, private schools can charge the tuition that they charge, and they can accept scholarships, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t charge on the top.

[00:16:03] So I’m just, I’m thinking about all of these things, and I am really happy, Gerard, I don’t wanna sound like a downer, that we’re moving in the direction of really empowering parents to make educational decisions. My fear is that we’re moving so quickly, we’re overlooking some of the really important components of what universal choice should look like and could look like, so that we can make sure that we’re not forgetting why we started this movement in the first place. Well, I can’t include myself in that, why you and others started this movement in the first place. And it was to ensure that there was better access, more equal access, if you will. And I worry that we’ve forgotten that lesson just a bit. As excited as I am to see so many of these programs opening up. So, from your perspective and given your history, Gerard, what do you think? Am I, worrying about nothing here?

[00:16:51]

Gerard: No, you’re worrying about the right things because you’re interested in issues of fairness, equity, and opportunity. And whenever you do that, [00:17:00] Naturally you should ask great questions. When we talk today about universal choice, the first thing that comes to mind for people who aren’t interested is that Gerard and Cara’s children are gonna suck up all of the seats.

[00:17:13] And there’s some concern, I mean, there’s some legitimacy for that because we have agency, we have social network, we know the system. And Gerard today could maneuver the system to make sure my children had an opportunity to get into one of those seats in ways my parents could not because they had agency of a different type, but definitely did not have the social network or the know-how to make that work.

[00:17:37] The absence of having my parents take advantage of it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do it. And what we’ve done for the last, I guess maybe 20 years of the movement, was to focus on the class-based argument of choice, which I still support that. We’ll pick a number, 300% poverty level, 250, 400, and we say, this is the cap. Anyone below this, you can get in. But what happens is that what about the family who made a $200, $300, $400 more than the cap? They’re not rich. They just happened to make more money. In fact, when I was in Milwaukee and when I talked to families in other cities, some people literally decided not to take a job promotion or raise because it would’ve put them out of the program. So, there’s a class dynamic there. Number two, and this is where I think the future of universalism is gonna go, is that when I have a Cara and a Kimberly, and when you two call 15 of your friends and you decide you want to support this program.

[00:18:40] The moms who don’t have the agency and the network are going to find ways to benefit as well because the assumption is that Gerard and Cara will take the seats. Maybe we will, but guess what? Maybe we won’t. We already have our children’s schools we like. We practice choice. It’s called buying a house in the right zip code.

[00:18:59] And so, even though you two don’t take advantage, guess what? We’re now going to be advocates for families who don’t have the agency of a social network to say, you know what? Here’s some seats that are open. What can we do to work for you? I think that in the absence of universalism, you’re not going to get the Kimberly’s, lemme not use you, the Kimberleys, the Karens, and the others. You know what? I probably shouldn’t use Karen in today’s. I was just gonna say, yeah. Let’s just say the moms who wouldn’t qualified for class-based choice. To have them in the movement is going to open up more doors for the moms who do not. And having seen 20 years of just the moms with the door, I’ve seen victories, BAEO, Black Alliance for Educational Options showed that there were victories.

[00:19:45] So it can happen and it’s happening now. I’m just saying the ESA in a certain way is the maturation of our conversations about vouchers in the ‘90s. And so naturally it would be an ESA versus a voucher, and naturally it would be universal versus means-tested. So, I’ve got a foot, one foot in one camp, one or the other. There’s a saying that someone who straddles the fence will have a sore middle. I’m okay having a sore middle if we can ultimately move the conversation toward closer toward opportunity. And if that means we’ve got to do it through universal, let’s talk about it.

Cara: We’ve got, of course, our guest waiting for us. Coming up, we’re gonna be speaking with Lauren Redniss. Need I say more. She’s the winner of a MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant. So that’s gotta be pretty cool. And so we’ll be back with Lauren right after.

Learning Curve listeners, we are back. We are with Lauren Redniss. She is the author of several works of visual nonfiction and the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant. Her book, “Thunder and Lightning: Weather, Past, Present, and Future,, won the 2016 Penn EO Wilson Literary Science. Writing award, radioactive Marie and Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout. What a great title. She was a finalist for the National Book Award and the basis for the 2019 Major motion picture radioactive the New York Times. Called her 2020 Book Oak Flat, A Fight for Sacred Land in the American West. Brilliant and virtuosic. She has been a Guggenheim Fellow. A fellow at the New York Public Library’s Coleman Center for Scholars and Writers, the New America Foundation and Artist and Residence at the American Museum of Natural History. She teaches at The Persons School of Design in New York City. Lauren Redness. Welcome to the Learning Curve.

Lauren Redniss: Thank you so much for having me.

Cara: Yeah, we’re really happy to have you here. Okay, so I wanna jump in, I have to say Marie Curie every year for Halloween, my kids’ school, instead of, picking a Halloween costume, they do something called Mystery History Day, where they have to pick somebody from history and dress up like them, and then give a short presentation of why that person is important. And Marie Curie is always in the mix with the little girls. You can just see a bunch of them like marching around the elementary school. It’s a lovely day. So I want you to tell us a little bit about her. She was named the Scientific Joan of Arc, and you know, our listeners should know she was in the renowned early 20th century Polish French scientist, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize, and the first person to win a second Nobel for her ground-breaking work in two different scientific disciplines, physics and chemistry. So could you tell us a little bit about Madame Curie and how is it that you came to her as a topic of study and how did you come to write?

[00:23:31]

Lauren Redniss: Well, first I just love that image of all the little children walking around as Marie Curie and because she really only had like about two different dresses that she ever wore for anything. I can imagine these, they all look the same. So identical. Marie Curie, she’s so charming. So where to begin? Well, I’m a visual artist, so. My work includes both writing, so like, as you know and as you’re saying, the work is nonfiction. It’s researched and reported like any other kind of work of general nonfiction, but there’s also this visual element where there’s artwork on virtually every page. So, for me, a subject needs to have to be expressed in both text and writing to draw me in, for me to need to make work. So in terms of, Marie Curie and her, role in history and what she represents, I mean, everything you said at the outset is of course true and she’s obviously a remarkable person and iconic. And the idea of the book is both to celebrate her achievements, but also to humanize her. I wanted to paint a nuanced picture of a woman who I actually think is a complicated person.

Cara: So. what do we need to know? Like, I mean, the little girls that are marching around as Marie Curie at my kid’s school, what should they know about, like, how she grew up about those things that, are sort of unspoken when we read about her wonderful accomplishments?

Lauren Redniss: Marie grew up as Maria Sklodowska in Poland, and Poland at that time was under Russian occupation. Her family was not a very well-off family. her parents were educators. So, she lived in this, intellectually rich and supportive environment. Apparently she taught herself to read when she was about four years old, and she was even like, apologetic about it because she sort of suddenly started reading her sister’s book and everyone looked so shocked.

She was like, oh no. But I, I couldn’t help myself. But, in addition to those, that political challenges that she faced because of the Russian occupation, and it was forbidden to speak Polish or to study in Polish there were those financial challenges that her family faced. In addition, her mother and her sister both died of tuberculosis when Marie was a child. So, there were those medical and emotional challenges. So, she was really dealing with a lot. And, of course, even just being a girl, there were limitations on the access to education for her. So, she in fact took part of what was, sounds like a pretty remarkable, I don’t know if you could call it in institution or organization that they called it the flying university or the floating university.

[00:26:06] It was an organic collection of people who educated girls at their different homes. and Marie was a part of that. But she was really desperate to get a formal education. So, she and her elder sister made a pact—a sister not, the sister passed away, obviously a different sister named Bronislawa, and her sister moved to Paris. And Marie worked as sent money to Bronislawa to support her. And then as Bronislawa established herself in Paris, she sent money back to Marie so that she could eventually come and study at the Sorbonne, which she finally did to become one of just 23 women who were studying at the university out of, you know, about 2000 students.

[00:26:50] Cara: It’s just amazing. And this idea of the flying university is something that I think resonates when we hear stories about women in countries today that don’t have access to education and [00:27:00] how they’re making it happen for themselves. Yeah, I want to talk about you and your work for a moment. So radioactive it’s a literary achievement. It’s also an artistic achievement, and it was the first work of visual non-fiction. To be recognized as a finalist for the 2011 National Book Award. So how is it that when you work, that you weave together images and writing and reporting and science? Can you tell us a little bit about your process?

[00:27:30] Lauren Redniss: Part of it is, relatively conventional. I’m working in an archive, you know, reading world letters and journals and diaries and I’m out recording and interviewing people. But then there’s this visual aspect that, you know, I’m always drawing wherever I go and I’m collecting different kinds of ephemera or taking photographs, all different kinds of resources that I’ll later be able to use as reference material for making the artwork.

[00:27:52] And then. I find a dummy book. You know, I approximate how many pages the finished manuscript will be. And I literally sew together a hard cover book, blank book, and I start xeroxing my sketches and cutting them up and scotch taping them in and I’m, you know, printing out my Microsoft Word document and I’m physically cutting it up and placing it.

[00:28:12] And so that’s how I sort of work out the pacing and the narrative arc of the book. That’s how I feel. I’m all for every type of access to reading material that people desire, online Kindles, whatever. But for me, like the physical object of a book is just like a perfect technology as is. And I love that element of surprise. You know, when you turn a page. And so, I try to think about how the reader is gonna feel when they move from one page to another. You know what? unexpected twist. Can you give in terms of the color palette, in terms of the written narrative. So, all of those elements are part of how the ideas are communicated.

[00:28:53] Gerard: So, I wanna read a quick quote and you could tell us more about it. So it goes, “Nothing in life is to be feared. It is only to be understood,”. proclaimed Marie. “Now is the time to understand. that we may fear less.” Could you talk about the lives, partnerships, the marriage of these two and how they were able, able to forge a mutual understanding of love and not only just about their life and their family, but also to accomplish so much in the world of a, you know, growing scientific world at the time.

[00:29:26]

Lauren Redniss: Yeah, it’s pretty remarkable, right? Like here you have these people, they seem to have this like great marriage, a beautiful family. They’re like winning the Nobel Prize over and over. I mean, it’s pretty extraordinary. I fear that I’ll sound kind of like some Instagram influencer, but I think that the Curies really had two things going for them. Shared priorities, and apparently from everything I’ve read of their letters, good communication and I think pretty early on they realized that work was the top priority for both of them. And in fact, like if you read Pierre Curie’s diaries, he had sworn off romance. You know, according to his kind of teenage writings, he said he thought that women were just a distraction.

[00:30:10] You know, maybe this was him writing, responding to an early heartbreak. Totally possible, of course. But what he wrote was, this isn’t gonna work for me. There isn’t, it isn’t possible for me to combine romance and the aspirations I have for my life. But then when he met Marie, I think it was quite an epiphany because he recognized that she could be his intellectual equal, that she could be his intellectual partner, and far from being a distraction, she would be, indispensable in his work.

[00:30:41] And I think that Marie similarly had come to Paris to get an education with the idea of returning to her family in Poland. But then, meeting Pierre, she realized that, this was actually the life that made sense for her staying and working and building a life with him.

[00:31:00] Gerard: Earlier you began to talk about your own education particularly in in art, in writing math and science. It all seems to come together. In fact, Marie once said, when radium was discovered, no one knew would be useful in hospitals. That work was pure science, and this is proof that scientific work must not be considered from the point of view of direct usefulness. Talk to us more about how, you decided to put together your own education, your own work, to create the kind of book that you have.

Lauren Redniss: First, I wanna just mention one thing about the quote that you read from Marie, which I think is really, really fascinating because points to some of the contradictions in her as a figure because in fact, Marie and Pierre were innovators in integrating pure science and medical research.

[00:31:48] They were actually some of the first scientists to put their research lab right next to a hospital, and Pierre Curie had this idea at one point to put a vial of radium on his arm and it damaged the skin. You know, unsurprisingly to us now. But this was part of a great insight that they made, that if radium could damage healthy tissue, it could also perhaps impede the growth of damaged tissue.

[00:32:12] And that’s how it became part of cancer treatments, which is, you know, still to this day called Curie therapy in France. So, I think that’s really, really interesting that she said that because, she’s a complicated person. In terms of my own education and how I found myself doing this kind of work I don’t have in really any formal education in science beyond the, like, you the schools would have, I had to really study up to be able to write this book.

[00:32:38] And I like to think that it is kind of an advantage because in doing my research, I read a lot of biographies of the Curies and I often found myself getting to these moments where they made their big scientific discovery, and not being able to understand the science of it, and therefore not being able to really feel the kind of dramatic import of that moment.

So, I felt like my duty in writing this book was to understand the science sufficiently to be able to communicate it clearly enough that a reader would be able to get that kind of emotional and visceral reaction to those moments of discovery, that they would actually feel them as opposed to just being told they were important.

[00:33:21] So, part of the way I did that was I would write the text and then after I had my full manuscript written, I brought it to a friend, the historian of science professor emeritus from Yale, Daniel Kevles. And he very generously sat with me and would go over the passages and tell me like, oh, well, you know, he would say, you know, the kind of most scientifically accurate way to phrase a certain idea.

[00:33:48] And then I would come back to him and say, okay, I hear what you’re saying, but. This version, because there might have been a different poetic approach that I wanted to get at in the phrasing, but of course I also wanted to get the science right so we would kind of navigate that together. And once he had signed off that both the science was corrected and I felt the poetry of the phrasing was correct, then I was good to go.

[00:34:12] Gerard: So, last question before we turn it over to you to read a passage of your choice. we’re celebrating Women’s History Month. Marie Curie obviously revolutionized our human understanding of physics and chemistry. She’s someone to recognize, but so are you, you know, your book earned many literary and artistic accolades. There’s actually a motion picture, Radioactive, based on your book, we could talk to our listeners about what it’s like having your work adapted into a film.

[00:34:38]

Lauren Redniss: Well I mean, the shortest possible answer is it’s really, really fun. for me, you know, I’m a super-duper control freak in my own work. You know, I do the writing, I do the artwork, I do the design. I design my own typeface for this book. Like there is no.millimeter on this book that I didn’t kind of finesse and tweak. So, when the book was optioned, I really just handed it over. I was like, okay, I’m just gonna sit back and see what you create.

[00:35:05] And I had no formal role in the making of the film. And I did go on set and I got to see like all of the incredible work of the art director and how they had gathered all the different materials to create in nineteenth-century chemistry lab and the clothing. And I mean, it was just so much fun, and I had no responsibility. So that was, really, really kind of wild to watch. And just to see like, you know, there’s some kind of what I felt were, maybe really personal or idiosyncratic choices that I made about details to include and to see those choices being brought into the script and then manifested, by an actor on screen and with this kind of glorious cinematography was, really extraordinary.

I have another book that was recently optioned and I think I’m gonna take a different approach this time if, that project moves forward. Because it’s a very different type of story with living people and an ongoing situation. So, I think, you know, again, like every project is really so unique and in this case it was just kind of magical to watch a bunch of creators, turn this book into something completely new.

Gerard: I’ll make sure to share this story with two of my three daughters. My oldest daughter works in Hollywood and the middle daughter is in her second year of an out-of-school time film class. And a couple of the films they’ve worked on were based upon books. So, I’ll keep that in mind. Well, we’re gonna turn it over to you to read what you’d like.

[00:36:34] And you know, behalf of Cara, I want to thank you so much for spending time with us. Great book. Look forward to future conversations and we’ll keep our eye open for the next adaptation of whatever work that work that—you already know that someone’s picked it up, or it’s just being optioned now?

[00:36:50]

Lauren Redniss: Well, yeah, so it’s been officially optioned and then it’s like the next step is to decide would it be for film or for television. And that’s the book Oak Flat that I mentioned.

[00:36:59]

Gerard: Yep. Okay, we’ll turn it over.

[00:37:03]

Lauren Redniss: Okay. Thank you so much. This passage takes place about a third of the way. Through the book, Marie and Pierre have discovered two new elements, radium Polonium, and they’ve also done the back breaking. Work to distill the mountain of material down to a small container of radium chloride.

[00:37:23] So it begins here at night:

“Marie and Pierre lingered in the lab to marvel at the way their samples of radium chloride glowed. Marie. These gleaming, which seem suspended in darkness, stirred us with new emotion and enchantment. The glowing tubes look like fairy lights. Radium was an instant commercial hit, yet the curious chose not to patent their findings. Marie: If our discovery has a commercial future, this is an accident. Pierre: it would be contrary to the scientific spirit. Others were less principled. Opportunists and charlatans wasted no time in capitalizing on the limited understanding of radium to market it as a wonder drug. There seemed no end to potential applications. Some mystical, some practical, many appealing to both impulses at once. Radium. It was said, could cure anemia, arteriosclerosis, arthritis, asthenia, diabetes, epilepsy, general debility, gastric neurosis, heart disease, high blood pressure, hyperthyroid, hysteria, infection, kidney troubles, muscular atrophy, neuralagia, neurasthenia, neuritis, obesity, rheumatism, senility, sexual decline. A fictitious Dr. Alfred Curie was hatched … radium face cream, radium laced toothpaste, condoms, repositories, chocolates, pillows, bath salts, and cigarettes were marketed as bestows of longevity, virility, and an all over salubrious flush. Radium was also touted as a replacement for electric lighting. Early electric light was both brilliant and blinding. The poet Robert Lewis Stevenson wrote “Such a light as this should shine only on murders and public crime, or along the quarters of lunatic asylums, a horror to heighten horror.” Even after the development of softer incandescent bulbs, some lamented that electric light would quote, never allow us to dream the dreams of the light of a living oil lamp had conjured up. The fragile glow of radium, on the other hand, offered a retreat into forgiving shadows and candle-lit. intimacy. Radium let the wistful romantic poses champion of scientific advance. A chemist named Sabin Arnold von Sochocky concocted luminous goulash of radium and zinc sulfide with dashes of lead, copper, uranium, manganese, valium, and arsenic, and sold it to the public as undark paint. Undark was marketed for use on flashlights, doorbells, and even the buckles of bedroom slippers. The time will doubtless come con Sochocky declared, when you will have in your own house a room lighted entirely by radium, the light thrown off by radium paint on walls and ceilings. Would in color and tone be like soft moonlight.”

[00:42:12]

Gerard: And so, my tweet of the week is from the US Military Academy, better known as West Point. On March 1, their tweet says, March is National Women’s History Month, and we honor the contributions of women to the US Military Academy, the army, and to the nation. I had an opportunity to have two women who were in the second class of VMI here in Virginia autograph a program where at that time I had an opportunity to speak to a group of educators. They happened to be in the room and seeing their uniform and, and knowing they were women. I knew they were one of the first cohorts, and so they autographed it was talking about their experience. Glad to celebrate National Women’s History Month. I’m glad to see us talk about their role in the military. [00:43:00] Cause even before they put on a uniform, women have been involved and supported the military in many different ways.

[00:43:06] Cara: Yeah, true that. I’ll take Women’s History Month. I’ll take women’s everything every day.

[00:43:13] Thank you for that, Gerard. Okay. We are gonna be back next week with Sir Jonathan Bate. He is a professor of English Literature and Senior Research Fellow of Worcester College and the University of Oxford. He is also, of course, the author of numerous scholarly books on William Shakespeare. So, we’ll be back with another fabulous scholar next week.

[00:43:34] Until then, Gerard, you take good care and I’m going to continue noodling what you told me at the top of the hour about ESAs. We’re going to see if we can get you to commit one way or another pretty soon.

Gerard: Sounds good to me. Sounds good. Take care.