In Mass, records are available on a “Why-Do-You-Need-To-Know” basis

Last week, MuckRock journalist Todd Feathers wrote about a recent change to Boston public records policy, introduced by the Walsh administration, which required that members of the media submit their requests through the City Hall PR office … even if those requests had nothing whatsoever to do with City Hall. It’s to assist in the processing, you see.

If that seems a bit off, that’s only because it completely is – requiring requests to go through some sort of external vetting process that doesn’t even involve the agency you’re requesting records from is a clear violation of Massachusetts public records law:

“Every person having custody of any public record, as defined in clause Twenty-sixth of section seven of chapter four, shall, at reasonable times and without unreasonable delay, permit it, or any segregable portion of a record which is an independent public record, to be inspected and examined by any person”

The fact that this vetting process only applies to a certain type of requester – a member of the media – is even worse, essentially making journalists into second-class citizens. When Todd pointed this out to Walsh’s office, they hastily clarified that it wasn’t a requirement, per se, but a very polite suggestion. With equal politeness, Todd declined, and continues to send requests to the agencies he wants information from.

Unfortunately, this arbitrary – and blatantly illegal – practice of making additional hoops for records requesters to jump through is nothing new in Massachusetts. Agencies frequently create convoluted forms that must be filled out and bizarre requirements that must be met before they do what they are required to do by law.

Statements of Financial Interests, of SFIs for short, are a perfect example. Under Massachusetts financial disclosure law, all state and county officials, as well as political candidates and public employees in “major policy-making positions” are required to disclose their and their immediate family’s private business association and other financial interests – the aforementioned SFI. The reasoning behind the law, and the benefit of making this information public, is rather obvious – if cushy contracts are being handed out to second cousins, people have the right to know. That’s cronyism 101.

Statements of Financial Interests, of SFIs for short, are a perfect example. Under Massachusetts financial disclosure law, all state and county officials, as well as political candidates and public employees in “major policy-making positions” are required to disclose their and their immediate family’s private business association and other financial interests – the aforementioned SFI. The reasoning behind the law, and the benefit of making this information public, is rather obvious – if cushy contracts are being handed out to second cousins, people have the right to know. That’s cronyism 101.

Which makes it all the more perplexing that they’re not public. A trip to the State Ethics Comission, which maintains the SFIs, shows plenty of helpful ways to file them – electronically, manually, even a direct line for assistance if you’re having trouble figuring out the form – but very little in the way of access. The “Public Access to Statement” page contains just the single line:

“The law provides that any individual who submits a written request to the Commission can inspect and copy any Statement of Financial Interests. The Commission must forward a copy of any such request to the person whose Statement has been examined.” (Emphasis added.)

Not only are the records not easily accessible – demanding a written request in the age of email is a fairly common “stall for time” tactic – but they must inform the public official that their theoretically public statement is being requested by a member of the public. Despite there being nothing in the law that would require them to do so.

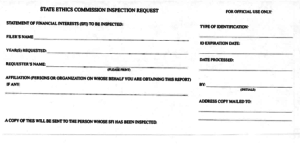

MuckRock has attempted to obtain a copy of an SFI like we’d obtain any other public document, emailing the Ethics Commission and reminding them of their legal obligation of providing access. And to give credit where it’s due, they’re more than happy to comply – so long as we fill out a form (a copy to be sent to the person whose SFI is being requested), and a legible copy of your driver’s license. The legible part here is key – your personal information cannot be redacted from your license, even though there are privacy exemptions that exist specifically to prevent this kind of information from being released via public records requests. Ironically, private citizens are not afforded the same privacy.

While there are a few select instances in which agencies can require photo ID, those situations are specifically related to privacy act requests, where the intent is to ensure that the person asking for information about themselves is indeed the person they claim to be. Asking for ID (ID that contains your home address, no less) as a requirement before being granted the privilege of access to theoretically public information on a theoretically public official – who has been informed of your request and whatever affiliations you might have – is utterly without precedent, and so contrary to the intent and spirit of transparency laws as to be laughable. And it would be laughable … if it was the exception, rather than the rule, in Massachusetts.

Next week, we’ll be taking another look at SFIs, and just how badly Mass’ record of disclosure compares with other states.

J. Patrick Brown is the Editor of Muckrock.com, an organization which facilitates public record requests and serves as an independent news source covering government transparency issues nationwide.