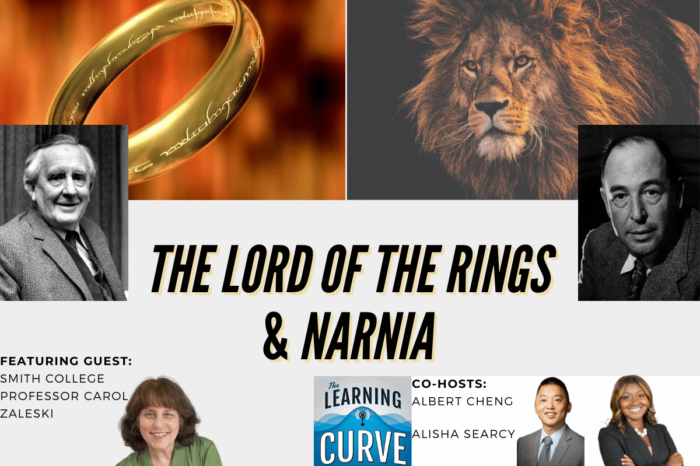

Smith College’s Carol Zaleski on The Lord of the Rings & Narnia

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Dr. Zaleski 12/20/2023

[00:00:00] Albert: Well, hello everyone. Good day to you and welcome to another episode of The Learning Curve podcast. I’m your host today, Albert Cheng, professor at the University of Arkansas and co-hosting with me is Alisha Searcy again. Hey, Alisha.

[00:00:38] Alisha: Oh, Albert. Glad to be back again. We should make this a regular thing.

[00:00:41] Albert: Yeah, that’s right.

[00:00:42] Albert: I know. Well, happy holidays to you too.

[00:00:46] Alisha: It’s been great so far. I’m looking forward to the rest of the year and I hope everyone is safe and enjoying time with family and loved ones and all of that.

[00:00:56] Albert: So actually, you know, I think this might lead right into my news story at the end.

[00:00:59] Albert: I thought I’d pull just kind of a historical reference here that last, I think it was Saturday the 16th, was the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. Actually, I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Boston and seen the reenactment.

[00:01:15] Alisha: I’ve been to Boston, have not seen the reenactment.

[00:01:16] Albert: Yeah, I, I remember when I was living there several years ago and I heard about the reenactment. I had to participate, and it never occurred to me that the Boston Tea Party happened right at this time of year in the heart of December. And certainly, being out there in the cold with all the reenactors put a new light a new understanding on that whole event for me.

[00:01:35] Albert: But it’s 250 years. just Google some of the articles that are out their kind of commemorating that, but certainly a big event in our nation’s history and all the more enlightening if you kind of imagine it happening right in the heart of a Boston cold winter,

[00:01:52] Alisha: Right? Definitely gives you new meaning.

[00:01:54] Albert: Yeah. I was glad to be bundled up. I’m not sure about the some of those reenactors, but anyway you have some news as well, right?

[00:02:01] Alisha: I do. So, the article that I want to talk about is about this great debate around retaining students or holding them back based on test scores or reading proficiency or whatever measure that states are using. And so according to this article, there are two research studies I talked about, one in 2017 in Florida and then another one that has multiple states.

[00:02:23] Alisha: And so, you know, I’m a mom, I’m also an educator, I’ve been a superintendent. And so, it’s interesting to me to read about this debate, right? So, on one hand you have, according to this article, educators who are saying they don’t like students to be held back, you know, there are interventions that you can do.

[00:02:40] Alisha: You can do all that you can to make sure they have what they need, but then there’s another school of thought. frankly, the research says and particularly in this study in Florida, the third graders in Florida, if given better instruction, I think that’s an important piece that they actually perform better in math and reading in their high school grades, they need fewer remedial classes, higher GPAs and students who didn’t get held back.

[00:03:07] Alisha: And then another study that looks at multiple states, also shows higher test scores in the later grades and reduces the need for remediation. And so again, this is what the research is saying. And then there are those who are in the school of thought that say, well, what about the emotional impact that this has on students if you’re being held back?

[00:03:26] Alisha: And I totally get that, right? From a young person’s perspective, you think, you know, I’m back with the same teacher or, you know, team. All of my friends are gone. That could take a toll. But there’s a Harvard researcher who was involved in the study, Martin West, who this is his quote. He says, my question would be whether they’re confident that the students wouldn’t have had an equally painful experience if they were advanced to the next grade and consistently faced content on which they were unprepared.

[00:03:57] Alisha: Yeah. I think that was a really good one. It really helps to kind of shore up for me why I think I fall on the side of if you need to retain a student, let’s do that. And Albert, here’s another thing, I wrote a piece maybe two weeks ago about a decision that our state board of education made here in Georgia, where they essentially lowered the cut score for reading proficiency for third graders.

[00:04:21] Alisha: And so just based on that reduction, once again, 20,000 students in Georgia were essentially told that they were proficient in reading when they were not. So, this is for me about telling students the truth and telling parents the truth about where these students are. Yes, you can do all the intervention that you want, but I think if a student doesn’t have the foundation in reading and math.

[00:04:47] Alisha: Maybe holding them back is the right thing so that they can then catch up. And then it looks like exceed expectations later on in their grades. What do you think?

[00:04:56] Albert: No, I think that’s absolutely right. I mean, you know, actually, I think a couple of episodes ago, we featured an article on grade inflation and I think we really at the point we were making then was we do kids a disservice families at a service when we essentially tell them that they’re ready to move on or are ready for the next step when they’re not.

[00:05:16] Albert: So, with you on this and we really have to look carefully at this and avoid telling families and kids that they’re more prepared or better than they really are. I know the truth hurts sometimes, but sometimes obfuscating that is just going to have worst consequences.

[00:05:29] Albert: So yeah, anyway, you know, got to do this. Well, this is careful, but don’t think I’m with you. Well, stick with us. After the break, we’re going to have Dr. Carol Zaleski to talk to us about the Inklings, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and some of the other folks in that merry band of men.

[00:06:01] Albert: Professor Carol Zaleski is Professor of World Religions at Smith College, where she teaches Philosophy of Religion, World Religions, and Christian Thought. Zaleski is the author of The Life of the World to Come from Oxford University Press, and is co-author with Philip Zaleski of The Fellowship, The Literary Lives of the Inklings, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, and Charles Williams. Another book, Prayer, A History, and The Book of Heaven, all but from Oxford University Press, and The Book of Hell, forthcoming from Oxford University Press. She is a columnist and editor at large for Christian Century, and has contributed articles and reviews to the New York Times, First Things, Parabola, the Journal of Religion, and the Journal of the History of Ideas.

[00:06:51] Albert: She earned her BA from Wesleyan University and her master’s and PhD in the study of religion from Harvard University. Dr. Zaleski, welcome to the show, it’s great to have you on.

[00:07:03] Carol Zaleski: It’s great to be here, Albert. Thank you.

[00:07:05] Albert: You’re the co-author. Let’s talk about The Fellowship, Literary Lives of the Inklings. It’s about a British literary circle, and I think most folks in the general public will know J.R.R. Tolkien and the creator of Lord of the Rings. They probably know C.S. Lewis, author of The Chronicles of Narnia. But they might know a little bit less about the other folks in there. So, could you start and briefly share with us, who were the Inklings? And how did all these folks, especially Tolkien and Lewis, then become among the 20th century’s most influential writers?

[00:07:38] Carol Zaleski: Okay, great. Well, it’s fun to talk about the Inklings. It’s a book I co-authored with my husband, actually. And at the center of the story of the Inklings is a kind of collaboration between friends and the core friends. that were involved in the Inklings, although friends of those friends are important too, are these two figures you just mentioned. C.S. Lewis who I think we can call the leading Christian writer of the 20th century.

[00:08:01] Carol Zaleski: There might be other contenders for that crown, but I think that’s arguable. And Tolkien, arguably the greatest writer of mythopoeic fantasy, I would say of all time. So, the two of them met in Oxford in 1926. By that time, Tolkien was The Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo Saxon, that is Old English.

[00:08:23] Carol Zaleski: And Lewis was a Fellow and Tutor in English Literature, also at Oxford at Magdalen College. And they discovered that they were kindred spirits. They had a shared love for old books generally, and for, especially for mythic stories, at first Norse mythology, and also for language study at first Icelandic.

[00:08:43] Carol Zaleski: But others do. But the other thing that they shared was a kind of a sense of, vocation, a calling to try to recover after a devastating world war, which they both served in and were wounded and wounded by anyway the various forms of art and life, which seemed to them to be in danger of vanishing. So, they had this shared commitment, and they would talk about all manner of things, some of it just academic politics, but all their, their shared interests. And with a few other friends, they just began to meet for conversation and long walks in the countryside. And from that circle came the Inklings.

[00:09:24] Carol Zaleski: They actually took the name from an earlier literary club. And they continued to meet for some 30 years. Twice a week typically. get together on Thursday evenings to read each other’s works and offer commentary and criticism and encouragement. And then they would also meet in a pub on Tuesday mornings just for fun. So that’s the Inklings. They didn’t see themselves as a movement. They didn’t have, you know, manifestos or placards, but they did really constitute something like a movement, if only because they did encourage each other to write the kind of books that they love to read, even though that meant bucking certain modernist trends. And I think, if people like the Lord of the Rings, it’s worth knowing that if it weren’t for the Inklings, and especially Lewis’s encouragement to Tolkien, we never would have seen the Lord of the Rings. It wouldn’t have seen the light of day.

[00:10:20] Albert: Would have been a great loss. Well, let’s talk a little bit about, I mean, you were talking about the literary tradition, really kind of referencing that the British literary tradition that, they were trying to revive and, preserve. And that encompasses a wide variety of legends, fairy tales, dramas, poetry, fiction and as you know, it draws upon many classic works the Bible, Beowulf, Chaucer King Arthur, you know, his legends Shakespeare, Milton, Coleridge — we could go on and on — but could you talk about some of the overarching themes found in British literature and how they particularly shaped and inspired the writings of Tolkien and Lewis when they were writing?

[00:10:59] Carol Zaleski: Yeah, actually it’s a complicated and really interesting question. To start with Lewis, Lewis was just really famous for his erudition, for his powers as a reader. I think it would be hard to list all the influences on him. and all that he was trying to preserve of the British literary tradition. He basically lived inside the whole, not just British, but the whole Western canon.

[00:11:21] Carol Zaleski: He was really at home with eras. So, I wouldn’t associate him or the Inklings as a group exclusively with fantasy. However. There is something special within the British literary tradition, a special preoccupation with fantasy. One way to describe that is the word fairy, faerie that is, has a kind of double meaning. There’s all sorts of legends about fairies and elves and goblins, ghosts, and trolls populating the British Isles and British folklore. So, there’s, fairy in that sense, fairy lands. But there’s also fairy in the sense of a kind of realm of imagination, which has been a really important theme in British literature.

[00:12:03] Carol Zaleski: And that I think is what, in many ways, what they’re trying to preserve. And that would include Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, great works of allegorical imagination, or gave us John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. It also gave us, you mentioned Coleridge, it gave us the poetry of the Romantics. It gave us this sort of neo-medieval art of William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, and the fantasy novels of, perhaps not as well known, but deservedly would be well known the Scottish clergyman George MacDonald, who was an influence on all the Inklings.

[00:12:40] Carol Zaleski: You know, you mentioned the Bible too, now that’s an interesting question. It’s certainly the case that the King James Bible has shaped all of English literature and language. But when I think about the Biblical tradition that Tolkien and Lewis carried on, there’s another aspect to it. There’s more than one English Bible. And they were very familiar with early vernacular retellings of Biblical stories in Old English or Middle English. And if you go back and read these Biblical narratives it’s almost like you’re hearing the Gospels for the first time, but only in a certain way, kind of like they’re being sung by a bard or, you have more of a sense of fate and heroic battles and dragons and magical spells, even in the retellings of the Gospel narratives that you find in, in Old English and in some Middle English texts.

[00:13:34] Carol Zaleski: And so, they were familiar with the Bible as part of that. Living English tradition and saw how much of the pre-Christian material that flowed into it was then kind of almost like alchemically transformed into the drama of Christian redemption. And I think that’s what they were trying to carry on, that really interesting mix of folklore, fairy [00:14:00] tale, biblical stories, and pagan beauty.

[00:14:05] Albert: Let’s maybe zero in on Lord of the Rings in particular. And so, Lord of the Rings, I think a poll in 1997 said it was the book of the century. Could you tell us briefly about his life. And you mentioned imagination how he as a scholar of Old English used his imagination to become one of the 20th century’s most celebrated writers.

[00:14:26] Carol Zaleski: Yeah, well, this is interesting. This poll the 1997 poll did reflect the immense popularity of the Lord of the Rings, but it was also greeted with horror by some, let’s say, highbrow literary critics. So, one of them, Germaine Greer, I remember saying, it was like my worst nightmare has been realized. Edmund Wilson saying, this is just juvenile trash, so, it’s very interesting to see, you know, why he was so reviled by certain kinds of critics and so loved by everybody else. It’s like, what was the heresy he committed? I kind of think it was the heresy of the happy ending, but that they thought it was juvenile because in their stories, things work out well in the end.

[00:15:13] Albert: Such a non-modern thing to do, you know.

[00:15:15] Carol Zaleski: Yeah, yeah, it’s not a modern thing to do. So, about his life, Tolkien’s life, I mean, I guess we’d have to look at that to figure out how did he become such a literary maverick? I think it’s partly because he really wasn’t part of the fashionable literary currents of his day Although he, you know, he was certainly familiar with modern literature and well-read and maybe not at Lewis’s level but certainly he was.

[00:15:38] Carol Zaleski: Anyway, let me just say a little bit about his life So, he was born in 1892 in Bloemfontein, which was the capital of what was called the Orange Free State in southern Africa. His father died when he was around three years old. At that point, he and his mother and younger brother were in England to escape the unhealthful climate they had been in.

[00:16:00] Carol Zaleski: And so, then they got news of the father’s death. So, they moved into a little town called Sarehole outside of Birmingham. It was a rather semi-rural hamlet with a working mill that meant a lot to Tolkien as he was growing up. So, their mother, now widowed, taught Tolkien and his brother everything, really for a while there before they went to school.

[00:16:25] Carol Zaleski: They were studying ancient and modern languages, the arts. Tolkien was a really gifted illustrator and artist, which she encouraged. Mathematics. She was quite brilliant and the other important fact about her is that she converted to Catholicism. During that time, and as a result was ostracized by her family.

[00:16:47] Carol Zaleski: And Tolkien believes that this is what led to her early death. She died from complications of diabetes when Tolkien was only 12 years old. So now he’s basically orphaned. He’s orphaned. But he was adopted by a priest, which is another interesting part of his story.

[00:17:03] Carol Zaleski: This is a priest who had been educating him his name is Father Francis he belonged to the Oratorian Order in the community that was founded by Saint, now Saint, John Henry Newman at Birmingham so obviously the Catholic strain in his early life is extremely important and remained throughout his life.

[00:17:21] Carol Zaleski: He went on to study at a school, King Edward School in Birmingham. And there he formed a very close-knit circle of friends, so this is kind of like the precursors to the Inklings who had very high ideals, both moral and poetic. Made a kind of pact with one another, that they would devote their lives to rekindling the light of beauty and truth and faith in our world.

[00:17:49] Carol Zaleski: But what happened was, they all ended up fighting in the First World War, and as Tolkien says, all but one of his close friends died in that war. By 1918, they had all died. So, there’s that element of tragedy and of commitment to beauty that, you know, is so important for understanding what Tolkien’s going to try to do with his sense of calling. Now part of that sense of calling for him is a love of languages, the literal meaning of philology. So, thanks to his mother, of course, he was exposed to many different languages. He also knew the Latin of the Catholic Mass. He talks about being enchanted by seeing these Welsh coal trucks passing by with the Welsh language on them the exotic language for him, really loved that.

[00:18:39] Carol Zaleski: I’d say though his main love is in the Germanic family of languages, that’s certainly his main area of scholarship, that is Old English and Gothic, the dialects of the West Midlands, which was his own part of England, and all of these regions where He could reconstruct what English was like before the Norman invasion and the Frenchification of English beginning in 1066. all of that figures in the kind of literature he would produce. I mentioned he served in, in the First World War. And in fact, began his creative work in the trenches. You know, it’s interesting, the philosopher Wittgenstein did that too. On the other side, you know, the other the opposing side.

[00:19:24] Carol Zaleski: All these people were writing great poetry in the trenches during these hideous, deadly battles. in fact, the dead marshes in the Lord of the Rings most people think are, based on or at least resemble the war scarred landscapes that he experienced, so, he was in the, infamous Battle of the Somme, so he experienced a lot of loss early on the loss of his close friends in the war, a sense of, the English countryside, his beloved Sarehole, losing its rural because of industrialization the sense of a kind of rupture in English literature and language brought on by the Norman Conquest, which he felt led to England being impoverished when it came to a national mythology.

[00:20:12] Carol Zaleski: England needed a mythology. So, he decided he would have to create one. It would be based on language. So, the myth, and he had this feeling that language is in a way the matrix of myth. Or at least that they’re very much intertwined. So, he was hoping for something that he could create, single handedly, quite an ambition something like the Finnish Kalevala, which, you know, brings together all kinds of, mythic strands, but unites them in a narrative.

[00:20:42] Carol Zaleski: And so, he hoped to do this, and he wanted to bring the pre-Christian, even pre pagan past of England. Into the story but connect it to the Christian drama to bring in themes of mercy and sacrifice and sin and redemption, all woven in with this mythology. And I don’t really know any other writer who’s ever done anything on this scale.

[00:21:08] Carol Zaleski: There was some precedent, like Blake kind of invented a mythology. But no one that I can think of had so singlehandedly put together and this is unfinished, but he, you know, went so far to have invented and evolving languages and consistent nomenclature and geography, creation accounts and different levels of history and different stories that are not always completely consistent because they’re meant to suggest oral traditions. That kind of rich backstory. I can’t think of anyone else.

[00:21:43] Albert: Or to put it another way, a friend of mine was asked the best universe out there, Star Wars or Marvel? And he said, no, it’s Lord of the Rings, the original.

[00:21:52] Carol Zaleski: Right. And you know, you need to then read the Silmarillion and the 12-volume History of Middle Earth and all the new material that Christopher Tolkien, before his death, was gathering from all the manuscripts. His son Christopher did a massive work in, retrieving the unfinished work. Lord of the Rings is just the tip of the iceberg. So anyway, he began this whole colossal project while he was in the trenches and also he came down with trench fever, so he had sick leave that probably saved his life. And then he continued it when he came back to England and took up his academic career. and then it continued you could say it was a hobby, but it was really more like an obsession.

[00:22:33] Albert: You were talking about some themes of Lord of the Rings has and of course you mentioned the Silmarillon and of course there’s The Hobbit which came before Lord of the Rings. What other themes are there? And I’ll ask two questions here. Yeah. Why is it that you know, folks, young and old alike, remain drawn to Tolkien, and what are some of the timeless lessons that are there for us to understand today particularly for our time?

[00:23:00] Carol Zaleski: Yes, well, it’s hard to talk at once about The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings because they are really different, and they were especially different when he first wrote The Hobbit. Tolkien was quite a family man and used to tell all sorts of stories to his children and send them letters from Father Christmas and, and all of that. And also, he had to work during the summers grading examination papers to keep the family afloat financially. Well one day as he was, he says as he was marking some student papers, and he was probably bored to death. This phrase just popped into his mind out of nowhere, it went like this, in a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. So, he’s got this phrase, and he’s going to take a story from it. And the story that he made, youknow, could be certainly described as a children’s book it came out in 1937, it was a popular book, so the publisher wanted a sequel.

[00:23:51] Carol Zaleski: Well, it took him 12 years to write the sequel, and all that time he was developing the mythology, the languages, the backstories, all of that. Not even backstories, he was, you know, creating, this corpus of legends, that was where his heart was, so what finally emerged from this 12-year process, with all sorts of false starts, was used to be called the New Hobbit. What was going to be the New Hobbit turned into a very different sort of story, which I would not call a children’s book. And it began to be sort of infused with, and it began to figure um, the mythology. That weren’t all present in The Hobbit, or certainly were very different in the way they appear in The Hobbit.

[00:24:35] Carol Zaleski: Like the wizards, you know, you can have a wizard in The Hobbit, sort of fits our popular idea of what a wizard is like, but once you get to The Lord of the Rings, you begin to realize that these wizards are a whole different order of beings that, they have this extreme longevity.

[00:24:53] Carol Zaleski: Or the, the elves who also have extreme longevity. They’re immortal as long as the world lasts. So, they survived these epic wars from the distant past, and they’re lingering in Middle Earth and they’re aware that they’re glorious fading. And then you have these orcs and the Ents, the tree shepherds, all of these characters that are coming in from mythology.

[00:25:14] Carol Zaleski: But beyond that gets to be a darker tale. And it’s interesting that I think a lot of the appeal of The Lord of the Rings what makes it resonate more deeply than The Hobbit is the element in it of loss and defeat, but of also a final redemption. It’s on a much deeper level. You can see that in the ring changed. At first you thought, you know, the ring was kind of a harmless magical device. But as he developed the sequel, Lord of the Rings version of the ring, you know, we find out that it was created by this dark lord, Sauron, to rule over all the different races of Middle Earth, the men, the dwarves, the elves, and so on. You have this ring and it’s the object and the cause of all these great epic wars. It has in it the power of this dark lord who himself is like a, a lieutenant of the original sort of satanic figure in Tolkien’s creation myth. Anyway, he’s created this ring. His power is vested in it.

[00:26:15] Carol Zaleski: He’s been partially defeated, but the ring is trying to get back to him. And if it does, if it succeeds, he will recover his power and use it to dominate and to destroy. Including the Shire itself, once he finds out that there is such a thing as the Shire. Because the funny thing is, it seems to be just by chance, the ring falls into the hands of this minor figure, this hobbit, Bilbo Baggins.

[00:26:39] Carol Zaleski: Up until now, the Dark Lord doesn’t know or doesn’t care about these funny little people. But now that it’s in the hands of a hobbit, the Dark Lord becomes aware of the hobbit and the Shire. And so now, this whole realm of these simple, ordinary, Sarehole-like shire folk, are in danger of becoming extinct. Everything that’s good and worth saving is on the verge of extinction at this point. So, the ring has to be destroyed. The interesting thing that I think Tolkien brings out here is that the defeat of Sauron can’t be accomplished by the strongest races of Middle Earth, the men, the elves.

[00:27:21] Carol Zaleski: So, the quest to destroy the ring falls to these simple shire folk, so to the hobbit Frodo, to his friends. Sam, Merry, and Pippin, who form a fellowship together with representative figures, loyal representatives of the races of elves and dwarves and men. Together they form this multi-race fellowship but without these humble and ordinary hobbits, they wouldn’t have succeeded.

[00:27:52] Carol Zaleski: And it’s partly because this is the one way you can outwit a power like Sauron, who knows only about the calculus of self-interest, of power, denomination. He only understands those things. But this fellowship with its simple hobbits at the core has a kind of resilience and also a willingness to sacrifice their self-interest that Sauron just couldn’t even think of.

[00:28:19] Carol Zaleski: And that’s how they’re ultimately able to defeat him. So, I think one reason that the tale is so enduring is that you have this group of ordinary hobbits that we can identify with. These are the kind of heroes we can identify with. And we can love them for their ordinariness, and also it brings a certain humor in, you know, when they’re singing, sing ho for the bath, and things like that.

[00:28:44] Carol Zaleski: These moments, because you go through this terrible long slog, and there’s so much misery, like going through the trenches. But then there were these, these moments of respite and refreshment that the hobbits can really, and that we can identify with. So, there’s that. I think also it’s basically just, it’s a great story. Tolkien had a certain theory about what great stories are like which we don’t really have time to go into. It’s like he executed on that. Yeah. it had deep roots in the British literary tradition, in human oral traditions and storytelling traditions generally.

[00:29:19] Carol Zaleski: But at the same time, it was very new. No one had ever done anything quite like it. Lewis when he reviewed it, and I forget for what, periodically he said, it was like lightning from a clear sky. Just completely unexpected. So, it’s this amazing combination of very traditional, rooted in the past conservative in a way, but also totally surprising and novel. And giving rise to then all the imitations that would follow.

[00:29:48] Albert: Yeah, Alicia.

[00:29:50] Alisha: Thanks for being here, this is quite fascinating. So, I want to switch gears for a moment and talk about C.S. Lewis, who was a British writer, an Anglican lay theologian, and author of The Chronicles of Narnia. So, could you talk about Lewis’s life, his faith journey, and how his experiences fighting in World War I powerfully shaped the moral message of his work?

[00:30:11] Carol Zaleski: C. S. Lewis. So, he was born in 1898 to an Anglo-Irish Protestant family in Belfast. Like Tolkien, he lost a parent when he was young. Like Tolkien, he fought in the terrible First World War, in the trenches. He was wounded. I mean, this was supposed to be the war to end all wars, right? He saw friends killed or maimed. And then he lived to, like Tolkien, lived to witness the Second World War after the war to end all wars.

[00:30:41] Carol Zaleski: So, like Tolkien, you could think of him as a war writer. like Tolkien also, he believed that the world we live in Both the natural environment and the culture was under siege by forces like, of Sauron, you might say. Well, maybe that’s over dramatizing it, but certainly forces of technocracy, materialism, certain kinds of dehumanizing modernization.

[00:31:08] Carol Zaleski: In they weren’t trying to turn the clock back, but they did have a sense of the culture being at risk and needing to be renewed through connection to things that used to be valued in the past So, as I mentioned Lewis lost his mother when he was young And he also his father continued to live but they got on badly He had a wretched experience of boarding school, first principal of the school he went to actually ended up in an insane asylum. He went to Oxford as an undergraduate which should have been really exhilarating, but his studies were interrupted by the war, so he spent his 19th birthday on the front line. At the notorious Battle of the Somme, again, by Tolkien. He was wounded by friendly fire, actually, and two companions were killed by the same British shells.

[00:32:00] Carol Zaleski: Wow. Which was terrible, he made friends with another cadet who had been stationed along with him at Keeble College in Oxford. The colleges of Oxford were turned into barracks, basically, during this period. Anyway, they made a pact with each other to take care of their one parent, they each had one parent, if one of them died, and Patty died in the war, so Lewis inherited Patty’s mother, Mrs. Moore and lived with her from 1918 until she was hospitalized with dementia in the 1940s, so you know, very unusual. Household life in which he was really caring for her a lot, doing a lot of the household chores and so on. During the Second World War, he and Mrs. Moore opened their home to children being evacuated from London.

[00:32:45] Carol Zaleski: So just like in the Narnia tales, children sent away from London, in this case to the suburbs of Oxford. He had some that lived with them. He also served in the Home Guard during the Second World War. after the death of Mrs. Moore Lewis eventually married a writer named Joy Davidman. And was very influenced by her and in the end of her life they did some collaborative writing together, and then he wrote a very searing memoir of his experience of her death. But just to describe Lewis, wow, I mean, he was a genius too, and in a lot of different areas. He began his academic career as a philosopher, but then he became a scholar of medieval and renaissance literature, especially courtly love poetry.

[00:33:37] Carol Zaleski: He was a defender of Milton’s Paradise Lost at a time when the critical establishment was kind of rejecting it. He also was a philosopher, and he would get involved in, public debates. He was a very vigorous, sort of no-holds-barred debater, and he worked his way through most of the philosophical positions that were on offer in his day and in his part of the world. So, he was a young atheist of the kind who shakes his fist at God for not existing. He was a believer in the life force while still an atheist at a certain stage. He was an idealist philosophy that was just on the wane in Oxford. And eventually a sort of generic theist, that is someone who believes in God, but not in terms of any sort of church doctrine.

[00:34:24] Carol Zaleski: All that time. even as an atheist, he loved the picture of the world that he was finding in medieval literature, most of which, of course, is Christian. But he thought that he couldn’t engage with that world because modern science somehow vetoed it. So, what convinced him otherwise, and led to his conversion, Not just to a generic sort of belief in God, but to Christianity was conversations with two of his very important friends, Owen Barfield a member of the Inklings, and Tolkien himself, and Tolkien who was Catholic while Lewis would remain throughout his life a member of the Church of England Tolkien from the managed to convince Lewis that if you love mythology, you ought to love Christianity, because there’s the myth that entered history, and became fact that was just one factor, I think it’s too complicated a story to tell all the reasons for his conversion to Christianity, but once he did convert to Christianity, he became in part because of talks that he gave over the BBC during the Second World War, a kind of voice of Christianity for millions.

[00:35:31] Carol Zaleski: And he came to see that as, during the Second World War, in addition to being the Home Guard, that was kind of his war work, was to defend the faith, to keep up spirits, and at the same time to defend literature, and the two things are related for him. And that’s the basic picture of Lewis, which I hope is covering enough ground for us to get a sense of, of his multifaceted genius.

[00:35:55] Alisha: Multifaceted and brilliant and compassionate to know that he took on someone else’s mother and took care of her. That’s beautiful. You mentioned a couple of times his academic posts at Oxford and Cambridge as a medieval scholar. And also, he became a popular writer. Can you talk about Lewis as a professor and his interactions with students and fellow faculty members and how they received some of his more popular works those religiously themed works like Narnia, The Screwtape Letters and Mere Christianity?

[00:36:29] Carol Zaleski: there’s a lot of student memoirs about Lewis and they tend to describe this guy with the red face and a booming voice. One anecdote about him is that he would start his lecture in the class, classroom lectures, he would start them as he was coming through the door and he would finish them as he was walking out the door, which I guess meant there wasn’t time for questions.

[00:36:51] Carol Zaleski: But anyway, he was very, very popular. Professor, teacher, he also tutored individually, and he was, you know, had a huge influence on, really thousands of students one way or the other. Some didn’t take to him like the poet John Betjeman, he was kind of a bete noire for him. He was also, as I mentioned, a debater.

[00:37:12] Carol Zaleski: There was a group called the Socratic Club where there would be debates between religious believers and atheists and so on, and he would take part in those debates. So as far as the reception of his popular Christian works goes, there’s a lot of variation Oxford itself, his colleagues and just the public in Oxford knew of him as a scholar and also as a very sophisticated lay preacher.

[00:37:39] Carol Zaleski: I mean some of his sermons were written up in the British press. Which named him Oxford’s new John Henry Newman, great Oxford preacher. And they knew him from his BBC radio broadcasts as a kind of really captivating evangelical soundbite person. And American evangelicals were flocking to the published versions of the BBC talks, that is, Mere Christianity, as well as Screwtape Letters, and works like that. But there were people who, for that very reason, looked down upon Lewis. the sort of people that were looking down upon American evangelicals.

[00:38:18] Carol Zaleski: Looked down upon Lewis as a kind of guilt by association and a lot of people knew him through Narnia and Screwtape but didn’t realize that he was also a really serious scholar and had other ways of writing about these religious themes that it wasn’t a theologian, but there was more theological sophistication in some of those two writings.

[00:38:42] Alisha: Interesting. So, I want to talk more about the Chronicles of Narnia. And of course, it’s considered a classic in children’s literature, having sold 120 million copies in 47 languages. Can you talk about briefly some of Narnia’s major themes and characters, and interestingly, the importance of the heroes being children who are called upon to protect Narnia from evil.

[00:39:06] Carol Zaleski: Yeah, I think it’s similar to the hobbits in Tolkien’s tales. You have what Tolkien called the Exaltavit humiles principle that is speaking in Latin from the Song of Mary when at the Annunciation, that God raises up the humble. And so, these are, little people who still have a certain kind of innocence, and they have a sense of wonder and also a kind of unprejudiced rationality.

[00:39:32] Carol Zaleski: Lewis really gives us that in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe when Lucy knows she’s been to Narnia and the others have to try to figure out whether to believe her. And the professor says, well, have you known her to lie? No. Have you known her to be unhinged in any way?

[00:39:49] Carol Zaleski: No. Then why not believe her? So, there’s that. I think again we can identify with the children who see things that adults sometimes. miss. one of the questions about the Chronicles of Narnia is whether it’s just a kind of preachy didactic allegory, kind of clobbering us with its Christian symbolism. The people that don’t like Narnia see it that way. Tolkien himself had reservations about it for that reason. If we were to believe Lewis though, Lewis, it’s kind of like the story of the origins of the Hobbit. Tolkien said, you know, that this idea of the hobbit, that the word hobbit just came to him.

[00:40:34] Carol Zaleski: Lewis says that for him, it just began with an image, an image of a fawn carrying an umbrella. And then these other images, the white witch, the lion, and he didn’t at first think, oh, this is Christian, you know, but because his mind and his heart were furnished with Christian themes and convictions, they kind of pushed themselves into the story somewhat the same way that the mythology for Tolkien pushed itself into The Hobbit sequel.

[00:41:08] Carol Zaleski: So, Tolkien criticized Narnia because it seemed like a sort of preachy allegory, but Lewis insisted that it wasn’t that kind of preachy allegory. He said, actually what it is, it’s not an allegory, but a supposal, an imaginative supposal, and the supposal starts like this. although it wasn’t what prompted the first writing of the Narnian Chronicles, that is The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

[00:41:34] Carol Zaleski: The supposal goes like this, what might Christ be like if there really were a world like Narnia and he chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as he has done in ours? So, a world, in other words, that has talking beasts, the fawn and other creatures are talking beasts, which is [00:42:00] something that Tolkien pointed out too is, I think we have a kind of nostalgia for it, a great desire to be able to communicate with animals, so we love to hear stories in which the animals can speak, so if you have a world made up of these talking beasts, and you want a kind of Christlike story, then it would make sense for the incarnation to take the form of this magnificent lion.

[00:42:25] Carol Zaleski: So that’s supposedly not allegory, but supposal. I think that’s debatable. But from that seed of imaginative supposal, everything else sort of derives from there. He didn’t — I don’t think he planned it all out, but eventually he would have a creation story in The Magician’s Nephew, an account of how evil came into the world, which would illustrate a point that’s extremely important for both Tolkien and Lewis.

[00:42:49] Carol Zaleski: They both shared the belief that everything that exists is good. The creation is good. So evil is only a privation or a distortion [00:43:00] or Lewis would call it a bending of that original goodness. So, there’s no absolute evil in the world. So, he would give us a creation story in The Magician’s Nephew and he would do this in other works as well that would give us a sense of how evil came into the world without positing some absolute evil force opposed to God. And then throughout all the Narnian books, you’d have stories of sin and redemption and spiritual adventures and an account of end times in The Last Battle, which with the last judgment. So, these are all themes that he developed in a lot of different ways.

[00:43:38] Carol Zaleski: And I think if, I were trying to help someone appreciate Lewis, who is turned off by the Narnian Chronicles, I would recommend reading his Space Trilogy, Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength, where you have a lot of the same themes at a more grown-up level.

[00:43:59] Alisha: Gotcha. So, you mentioned his use of animals. I would love to ask you about Aslan, who’s a major character in the Chronicles of Narnia. And unlike any other character in this series, he appears in all seven chronicles and is depicted as this talking lion. And described as the king of beasts, the son of the emperor over the sea, and the king above all high kings in Narnia. So, can you talk about Aslan, his symbolism, as well as Lewis’s role as a Christian apologist in a sweepingly secular age? And you talked about that a little bit earlier.

[00:44:32] Carol Zaleski: Yeah. So obviously Aslan is a Christ figure. And you have basically the crucifixion and resurrection, spoiler alert, in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. I think what makes that work effectively as a kind of retelling of the Gospel, yet also be universal in appeal so that people that don’t want to be preached to about Christianity can still love it, is how he depicts the talking beasts and the children responding to Aslan. In some ways that’s the best way to try to give a literary portrait of Christ is in the eyes of those who respond to him.

[00:45:15] Carol Zaleski: So, you know, it’s like Jesus is saying, you know, who do you say that I am? And people are responding to that question because there’s a mystery at the center. Of a Christ figure which isn’t going to be able to be fully revealed in any story but the response of people to that Christ figure, in this case Aslan. It’s going to reveal as much as one needs to know in a sense about, the whole symbolism and doctrine that’s being conveyed there. Yes, he’s a talking line. He also sings in the creation narrative. And this is something you find in Tolkien’s creation myth as well, that you have the creator sings the universe into existence.

[00:46:02] Carol Zaleski: Wow, I think that’s interesting because it’s the idea of, you know, in the beginning was the word. Creation happens through the word of God, just saying, let there be light, you know, but depicting that as singing has a, is a wonderful idea. I like that.

[00:46:17] Alisha: So finally, J. K. Rowling, author of Harry Potter, who has sold more than 600 million copies worldwide, making them the best-selling book series in history, commented that as a child, she enjoyed reading C.S. Lewis and was also influenced by J.R.R. Tolkien. We’re living in an era of great cultural divisiveness, sadly, and so would you talk about the Inklings’ wider spiritual, moral, and literary legacy across our modern world?

[00:46:46] Carol Zaleski: Wow, thank you for that question, Alisha. Yeah, I think they speak to and reveal to us, if we haven’t been noticing it, that there’s a great hunger for transcendence. For hope especially hope in situations where there’s a lot of defeat and cultural decline. I mean, that is so much the theme of Tolkien’s work.

[00:47:10] Carol Zaleski: Actually, he was once asked what the main theme was, and he said it was death, death, and immortality. But, but really, I think it’s about hope in the face of defeat and cultural decline. And we have a real hunger for that. And also, for reading in a way it’s kind of an endangered art. Louis said that reason we read is that we want to see with other eyes, not just with our own. And if we could do that, we would have more charity towards others as well, more capacity for understanding perspectives different from our own. There’s a hunger for faith, and they’re able, and this is something you don’t find in much modern literature, to offer a kind of faith, a kind of hope most of the time without being too cloyingly sentimental or superficially self-help like, and I think the reason for that is, their own erudition, that is that they were steeped in a great intellectual tradition and imaginative tradition, which has both moral and entertainment value. So, I guess that’s what I would emphasize. I think there are shared ideas about evil, about providence, about friendship and fellowship. About vocation. All of these things are themes that they deal with each in their own way, but it’s a shared treasure.

[00:48:39] Alisha: I love that. And so needed. So, as we close out this interview, Dr. Zaleski, we would love you could read for us, perhaps one of your favorite paragraphs or passages from your latest book?

[00:48:51] Carol Zaleski: Well, I guess to kind of continue with talking about their legacy, there’s an epilogue here, which we call the Recovered Image. [00:49:00] So I’ll read a little bit from that. So, talking about the Inklings as a whole. So not just Lewis and Tolkien, although they’re the stars of the story, but also Owen Barfield and Charles Williams who are important in our book. my husband Philip Zaleski and I say that the Inklings’ work, taken as a whole, has a significance that far outweighs any measure of popularity, amounting to a revitalization of Christian intellectual and imaginative life. They were 20th century romantics who championed imagination as the royal road to insight, and the medieval model, as Lewis called it, as an answer to modern confusion and anomie. Yet they were for the most part romantics without rebellion, fantasists who prized reason, for whom fairy was a habitat for virtues and literature a sanctuary for faith. Even when they were not on speaking terms, I should comment that did happen. But those are stories we can’t get into today for, anyway, not, not forever, but there were times when they fell apart.

[00:50:08] Carol Zaleski: But even then, they were at work on a shared project to reclaim for contemporary life what Lewis called the discarded image of a universe created, ordered, and shot through with meaning. Thank you very much.

[00:50:23] Alisha: It’s been so great to have you. This is a new area of literature for me, so I learned a lot today and I’m grateful for that.

[00:50:31] Carol Zaleski: Well, thank you, Alicia and Albert. I really enjoyed the conversation.

[00:50:36] Albert: Yeah, it was huge pleasure. I mean, I’d love to sit and go on and on and on. Yes. So much to talk about. But thanks for taking your time and being here.

[00:50:42] Carol Zaleski: My pleasure.

[00:51:12] Albert: Now moving to the Tweet of the Week. This one comes from U. S. News Education. The Duolingo English test, a computer adaptive language proficiency exam, is gaining momentum as a way to measure the language skills of prospective international students applying to U.S. colleges and universities. So, check out that link. we’re always seeing a bunch of technology change the way we Practice education change how our educational institutions are evolving being influenced by that. I think there’s just another one that caught my eye this week. least I don’t know if you are familiar with the procedures and application process of international students coming to the US for college but have to take additional exams about English language readiness. And so do a lingo, apparently has a computer adaptive test. And so, this is one that applicants from other countries can take remotely. But it’s computer adaptive unlike now, the TOEFL or some of these other exams where the set of questions is, already sets.

[00:52:26] Albert: This one. Kind of adjust. If you get an answer correct, it’ll start asking you a more difficult one and vice versa. And then basically gets you to land at what your level is at and report your results pretty quickly. So that’s more accurate sounds. Yeah. Yeah. I think there’s some gains there.

[00:52:41] Albert: Certainly access, I think is going to be something that’s going to change. You know, kids can take this from home. So, take a look at that tweet always lots of stuff advances, changing the way we do education. Yes. Alicia, it was great to co host another show with you, glad to have you on.

[00:52:58] Alisha: Yes, as always, Albert, great job, very interesting today, and I look forward to being on with you again.

[00:53:03] Albert: Yeah, that’s right. In the new year. So happy holidays. Happy new year, everybody. We wish you that from the Pioneer Institute look out for our next set of episodes coming this January in 2024. See you next year.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Prof. Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas and Alisha Searcy interview Smith College Prof. Carol Zaleski. She discussed her co-authored book, The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings including J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, renowned for their literary and moral impact. Prof. Zaleski covers Tolkien’s life, the success of The Lord of the Rings, and its enduring themes. Additionally, she delved into C.S. Lewis’s experiences, his role as a professor, and the timeless lessons in The Chronicles of Narnia. Her discussion extends to the broader legacy of the Inklings, influencing J.K. Rowling and resonating in today’s culturally divisive era, emphasizing their spiritual and moral contributions. Prof. Zaleski closes the interview reading an excerpt from her book The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings.

Stories of the Week: Albert discussed a story from Politico about Boston commemorating the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party with reenactments and community events; Alisha commented on a story in The Washington Post about the debate on retaining students based on test scores.

Guest:

Carol Zaleski is Professor of World Religions at Smith College, where she teaches philosophy of religion, world religions, and Christian thought. Zaleski is the author of The Life of the World to Come (Oxford University Press), and is co-author, with Philip Zaleski, of The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams; Prayer: A History; and The Book of Heaven (Oxford). She is a columnist and editor-at-large for Christian Century, and has contributed articles and reviews to The New York Times, First Things, Parabola, The Journal of Religion, and The Journal of the History of Ideas. She earned her B.A. from Wesleyan University and her M.A. and Ph.D. in the study of religion from Harvard University.

Carol Zaleski is Professor of World Religions at Smith College, where she teaches philosophy of religion, world religions, and Christian thought. Zaleski is the author of The Life of the World to Come (Oxford University Press), and is co-author, with Philip Zaleski, of The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams; Prayer: A History; and The Book of Heaven (Oxford). She is a columnist and editor-at-large for Christian Century, and has contributed articles and reviews to The New York Times, First Things, Parabola, The Journal of Religion, and The Journal of the History of Ideas. She earned her B.A. from Wesleyan University and her M.A. and Ph.D. in the study of religion from Harvard University.

Tweet of the Week:

https://x.com/USNewsEducation/status/1734317256409059370?s=20