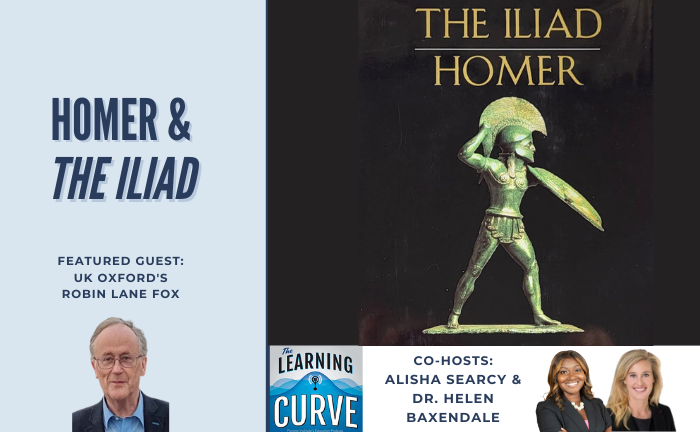

UK Oxford’s Robin Lane Fox on Homer & The Iliad

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Robin Lane Fox

[00:00:00] Alisha Searcy: Welcome back to the Learning Curve podcast. I’m one of your co hosts, Alisha Thomas Searcy. Albert is out, but we are joined by guest co host, Helen Baxendale from Great Hearts. Welcome.

[00:00:34] Helen Baxendale: Thank you, Alisha. It’s great to be with you. I am a longtime listener, one time guest, and now delighted to be stepping in for Professor Cheng in his absence and co hosting with you.

[00:00:44] Alisha Searcy: Yes, excited to have you. Why don’t you remind folks who you are and what you do?

[00:00:49] Helen Baxendale: I am with Great Hearts Academies, which is a large network of public charter schools spanning Arizona, Texas, and Louisiana. We’re a K 12 network that teaches the classical liberal arts model of education. We have about 30, 000 students in 50 academies and hoping to expand that number in coming years.

[00:01:12] Alisha Searcy: Outstanding. Well, we’re again, very excited to have you. We’ll have a fun show today. So looking forward to that. But before we get to our guest, I would love to hear what you’re reading these days.

[00:01:24] Helen Baxendale: Well, thanks, Alisha. So there was a lot of interesting education news at the moment, but the piece that caught my eye this week was written by Daniel Levin, who is.

[00:01:34] It’s a middle school ELA teacher in Brooklyn and he had a piece in Chalkbeat, New York called Teaching English Has Gotten Away from Exploring Literature, That’s a Problem. And so this was a piece that is dear to my heart because one of the sort of touchstones of classical education and certainly one of the things we pride ourselves on at Great Hearts is introducing children to great books.

[00:02:01] And trying to encourage a love of reading because reading great books helps form us as people, not just the kind of mechanics of ELA, which tends to be what is tested for and therefore what is prioritized in a lot of ELA instruction these days. Mr. Levin was lamenting that English language instruction has become for him a little bit deadened and far too kind of utilitarian because He feels compelled to sort of teach to the test that state standards are really interested in things like, you know, discerning the main idea from a passage and, you know, the syntax and mechanics of a sentence rather than what the story might tell us about the human condition and what we might learn about ourselves.

[00:02:46] So it’s a tension that we deal with all the time is as educators. We certainly. you know, value what the state tests can tell us about how well kids are developing these kinds of important skills. But we would hate for the tail to kind of wag the dog. And I thought this piece really beautifully captured some of those difficulties and tensions that, you know, educators are wrestling with between.

[00:03:10] Testing for skill mastery and then preserving kind of the magic of reading great books and literature. So I would recommend that story to our listeners this week.

[00:03:22] Alisha Searcy: I love that. And it’s so appropriate for you to bring that story forth, of course, given the work that you do every day. And I think there’s a larger conversation too about curriculum and what students are learning, what we want them to know.

[00:03:34] I think the point that you made when you first started was like, we just lost. In some ways, I don’t think with everybody, but we’ve lost in some ways, inspiring kids to just want to be lovers of reading and knowledge and information and imagination exploration. And so I appreciate you bringing this forth and I hope our listeners will check that article out.

[00:03:56] I want to talk about an article that I saw in the K 12 Dive, and the title is Concerns Mount Over Potential Loss of Medicaid Funds for Schools. And I picked this article because, you know, we’ve been talking about, of course, the impact of Changes to the Department of Education from the federal level and I’m not going to make this political in any way, but this was information for me because I did not realize that Medicaid funds were the third largest funding stream essentially from the federal government to public schools in the country.

[00:04:32] What I also didn’t realize until I read this article is just how important Medicaid is and specifically when it comes to providing health services to kids who need critical health care, kids who have IEPs who are getting school based Medicaid services. So we’re talking about 7. 5 billion worth of services that students are receiving.

[00:04:55] And so I think it’s just important to pay attention. I think what I’m learning in this current environment is just the value, frankly, of the Federal Department of Education. So whether it’s talking about Title I funds and making sure that low income students and families have resources that they need to have access to a great public education, or whether it’s students with special needs.

[00:05:18] I have a kid with an IEP. I understand how important it is. And I’ve also been a superintendent, so I’ve been on both sides of the table. when you’re trying to make sure that number one, the federal laws are in place, that those protections are in place for kids that you’re doing right by them at the school level.

[00:05:35] And the federal department of education is there to make sure that states and districts are in compliance. And now, you know, adding Medicaid to that. It’s just so important to think about the services that are provided and how much schools depend on these things to make sure we’re, we’re meeting the needs of kids.

[00:05:53] So an interesting article, I would encourage our listeners to read and learn more about how Medicaid services are really helping even our youngest learners, like in Head Start programs. So interesting piece.

[00:06:07] Helen Baxendale: Yeah, very interesting. I was not aware of that link between, you know, Medicaid and school funding either.

[00:06:12] So I’ll have to check that out.

[00:06:14] Alisha Searcy: Exactly. The more you know. So I’m looking forward to our show today. When we come back, we have Oxford’s Robin Lane Fox talking about Homer’s Iliad. Stay tuned.

[00:06:39] Robin Lane Fox is emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford, and reader in ancient history, University of Oxford. He is the author of Alexander the Great, Pagans and Christians, The Long March, Xenophon and the Ten Thousand, The Classical World. Traveling heroes, Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer, Augustine, Conversions to Confessions, which won the Wolfson Prize for History.

[00:07:06] According to The Spectator, Homer and his Iliad is the product of a lifetime’s contemplation of study, a stirring introduction to the sometimes alien Homeric world. Lane Fox was educated at Eton College and he studied Classics at Magdalen College, Oxford University. Professor, you are a celebrated classicist on enduringly great ancient Greek myths, poems, and histories.

[00:07:32] Would you share with us a bit about your background and how you first became interested in Homer’s Iliad, as well as why the Trojan War and this poem should matter to students in the early 21st century?

[00:07:44] Robin Lane Fox: Okay, well, me first. I was privately educated in England, and I started learning Ancient Greek at the age of 10.

[00:07:52] By the age of 13, I first encountered a book in Greek of the Iliad, the right way, not with a translation, Book 6. And even though I was fascinated by sport and looking out of the window, this book intrigued me. We then had to read two great books in two separate terms. Book 22 and Book 24 in our own time as extra work and be examined.

[00:08:17] Well that’s not a very good start for any book, but again I was swept away, as all readers in the end always are, by these two wonderful parts of the Iliad. And then can you imagine, between the ages of 16 and 18 at school, we followed and went through the whole of the Iliad twice. So I came to university knowing it.

[00:08:39] At university, the teaching was really rather dry, very antiquarian and linguistic. Nobody really answered a basic question, why does the Iliad make us cry? But I started teaching in 1973, think of that, and I taught it on and off for nearly 50 years, and still the poem grabs me. Why? Because of its extraordinary humanity.

[00:09:04] I’ll discuss more the pathos. The irony, the extreme vividness, and I think the exactness of so much that it observes the characterization which is there and the feeling that we know. So dreadfully what is gonna happen? It’s a question of how will it happen? It’s not a poem of suspense very much, but it’s a poem of agonizingly onlooking, seeing the dreadful events that will unfold.

[00:09:33] And the reason it still touches us is these patterns still recur. In wartime, in interpersonal relations, in the values we see around us, they’re not as remote as people say. In the Ukraine now, in the Sudan, who knows where, warriors are going out facing the same dreadful choices for the sake of their families, their cities, and so on.

[00:09:55] And Homer is so extraordinarily alive to the pathos of war and death and loss.

[00:10:04] Helen Baxendale: Professor, thank you for so brilliantly evoking the poem’s enduring relevance. I wondered if we could take you in the opposite direction now and you could help us better understand the historical context from which the Iliad springs.

[00:10:18] Could you share with us what we know about Homer and the ancient Greek epic oral tradition and how they have powerfully shaped Western poetry and literature for now millennia?

[00:10:29] Robin Lane Fox: Well, I can indeed. If we knew the answers, I wouldn’t be writing a book. There would be no point you could refer to them. We have to guess, we have to infer, and we know nothing contemporary about Homer at all, I think, except possibly one pun, I argue.

[00:10:46] on his name. But we can infer from his poem that he was familiar with and surely composed in the area around Troy in western Asia Minor. He knew the coastline, he knew the topography very well. But what we can definitely say from close study of the language is that there had been generations of Orally composing poets in Greek before him, and it’s from them that he’s learned so many of his turns of phrase.

[00:11:15] The skill is the way you put them together, you invent a plot, and you innovate. He has that skill too. And I put him, I think the majority of scholars do, but of course not those who write books with something different to argue, I put him a little earlier than some, 750 to 730 BC. But the point I want to emphasize is that he and his predecessors composed orally.

[00:11:43] They didn’t compose by memorizing the poem. They had no text, and the only alternative I can see to explain why we have a text is that Homer, in the end, was persuaded to dictate one. And I think he dictated it because it was so valuable for his family. They could then control it, and other people could pay to learn it and look at it.

[00:12:07] Now once it’s a text, it can influence subsequent literature the whole way through the world. We wouldn’t have Virgil without Homer. And again, that’s absolutely a crucial thing. And of course, epic, so important again for John Milton, the English poet, who’s aware of the level of grandeur in Homer, though his subject is so, so different.

[00:12:28] And in so many touches in poetry, Homer is the founder. One simple example, he likes comparisons as when two trees rub together and fire ignites them on the mountains, for instance. Horribly modern in our awareness of forest fires, so did the fire of battle rage across the plain. It’s from Homer and his example that all Western narrative poets, whether it’s Dante, whether it’s Milton, whether it’s, for instance, Matthew Arnold, use similes.

[00:12:59] comparisons and the whole idea of epic as something noble and apart from us, a story with a plot and great deeds and actions. This derives from Homer. He is fundamental and the ancients recognized it.

[00:13:14] Alisha Searcy: So I want to talk about Achilles for a moment and just for information for our listeners, the Iliad is divided into 24 books and contains 15, 693 lines and said, and said, towards The end of the Trojan War, a 10 year siege of the city of Troy by an alliance of Greek city states, and it traces the rage of Achilles, the celebrated warrior and his conflicts with King Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks.

[00:13:42] So could you tell us, Professor, about Achilles, his conflicts with Agamemnon and King Priam of Troy? And Prince Hector.

[00:13:51] Robin Lane Fox: Yes, I mean the poem is already extraordinary. It’s about an emotion, a wrath, only about 1920 days of action, and not a long poem where one episode comes after another like so many other epic poems, or let alone those known in Near Eastern languages.

[00:14:09] And Achilles was a great hero, with his family roots, we’re told, in Thessaly, in northern Greece. But he’s special. We have to remember, he’s nearly superhuman. His mother is a sea goddess, Thetis. He is bigger than men are nowadays. He has a strength that none of us have. He’s amazingly beautiful to look at.

[00:14:30] And of course, he is swift footed, he can run so fast. At the start of the poem, he is not, in fact, Just in a temper. He is insulted by the leader of the whole expedition, King Agamemnon, the great king of Argos and Mycenae, the great seats in Greece. Now this is perfectly extraordinary. Homer produces a poem in which the leader of the Greek forces is actually inept.

[00:14:57] He completely ruins it, and Achilles takes umbrage, he’s threatened by Agamemnon, and then his temper escalates, and he refuses to fight anymore. And he gets his mother to pray to the God Zeus that the Trojans will be allowed to press very hard on the Greeks that will be killing a lot of the fellow soldiers until they come to him and shower him with honor.

[00:15:23] And then he will return. So he is badly treated. By what should have been the noble leader of the expedition, he withdraws in a stupendous rage, though he’s a wonderful speaker, the best of all speakers in any epic, and he sits on the sidelines whilst his own side, the Greeks, Suffer greatly at the Trajan hands and then in a wonderful scene, book nine, if you’re reading, the Greeks do try to send presence to persuade him, but Agamemnon doesn’t go.

[00:15:56] The leader doesn’t come himself and Achilles just rejects them. He said the insult to him is still too great. But, eventually he allows his lifelong friend, his beloved Patroxys, to go out wearing his armor into battle. And then we learn the sting in the tail. Patroxys is killed by the god Apollo. And Achilles then changes from incredible wrath with Agamemnon to a determination to take revenge on the Greeks.

[00:16:29] But the poem has this extraordinary further shift that it ends with Achilles receiving King Priam, the king of Troy, the little city they’re trying to take in northwest Turkey, and King Priam himself, old and virtually alone, goes out by night to try to reclaim the body of Hector, his great son, whom Achilles, in his rage, has killed, and Anything you would imagine could have happened, and yet, I may read it at the end, Priam comes into the heart, Achilles is amazed to see him, absolutely extraordinary, as if Zelensky were to go to Putin, and then there are scenes of extraordinary humanity between the two of them that still overwhelm.

[00:17:19] Every reader. This is not a poem about just war and slaughter. It’s a poem about the human predicament, about the pathos of war and loss, about death and about fate and the cruelty and unpredictability of the gods. It sweeps us along and Achilles is the towering presence. I think the greatest central figure hero in any epic.

[00:17:47] Wow.

[00:17:48] Helen Baxendale: Thank you, Professor. I’d like to pick up on the cruelty of the gods, which you just mentioned. The apple of discord was a golden apple dropped by the goddess of strife that sparked a vanity fueled dispute among the goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite. And this led to the judgment by the mortal Paris and ultimately the Trojan war.

[00:18:09] And I wondered if you could discuss this mythical episode and the role that the gods. and goddesses play in shaping the events and characters leading into the Iliad?

[00:18:18] Robin Lane Fox: Ah, well, that’s an absolutely fascinating question. And remember that Paris is King Priam’s son. Now, we are not directly told in the early books about The so called judgment of Paris when Paris chooses beautiful, sexy Aphrodite as the most beautiful goddess.

[00:18:36] But what we find is that Hera and Athena are implacably opposed to the city of Troy and the Trojans. They will show them no mercy because they feel they have been insulted and we don’t really know why. But the audience knew because they were all totally familiar with this great scene of judgment.

[00:18:55] Homer takes it for granted. And on the other side, Aphrodite is pro Trojan. So it is important for the alignment of the gods. Now you ask a great question. Generations of readers in modern times, often very Christian, and you know, have a totally different view of what the relationship in a single god in heaven think.

[00:19:17] This is all very charming, and the scenes among the gods with their quarrels, their favorites, their friends, their moods, emotions, their anger, their loves, and their endless heedlessness, where in the end they banquet in heaven. They think all this is just light poetic relief. I profoundly differ. I think the crucial thing is that Homer and his audience have envisioned and imagined their gods as enlarged versions of the aristocrats who governed the cities that they lived in on earth.

[00:19:52] They are what I call the Supercrats. They, too, give to those who give to them. They’re random in their favors. They’re obsessively concerned for their own honor. And in the end, however much they may love you or I, they don’t give a below. They will sit and have their own feast and forget it amongst themselves.

[00:20:13] Yes, they may well have sex with an outside woman. They may well have a particular favorite for a while. This is so striking, the projection into heaven of all the social relations that were taken for granted. Very difficult for us to see now, not living in aristocratic worlds, in aristocratic life. on earth.

[00:20:33] And this is not a poetic invention. It is a widely held view of what life is like in heaven. And you can parallel this sort of enlargement of earthly relations. A very simple example in Christian circles, we talk of patron saints. Why are they patrons? Because on earth, people at the time had earthly patrons who gave them work and looked after them.

[00:20:57] So in heaven, there must be even greater saints who are patrons. It’s that way of thinking, or angels become like courtiers in the great court of heaven, like the courtiers at a contemporary monarchy. So far from being a just light poetic relief we’re meant to smile at, this is a deeply held And unquestioned view of the way the gods carry on, and my god, they can be cruel at random.

[00:21:24] And Christians can withdraw and think, can this really be right? They’re so hard on Hector, for instance, when Athena Cheats him in the final encounter with Achilles, and dear Hector, the great Trojan hero, is killed. Indeed it is right, because one thing Homer is saying, you never know with the gods. You can’t know.

[00:21:45] Their random whims account for the random distribution of disaster, catastrophe, death, and failure in the world. Very, very powerful, and that’s the leap that readers need to make.

[00:22:01] Alisha Searcy: That is powerful. Professor, there’s a famous line from the Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe that says, quote, Was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

[00:22:15] Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss, end quote. Can you talk to us about what students should know about Helen of Sparta, her relationship with her husband, Menelaus? The Greek of Sparta, the Trojan Prince Paris, and their importance to the overall narrative of the Iliad.

[00:22:34] Robin Lane Fox: Yeah, this is of course a great question.

[00:22:35] This is wonderful Helen, brought up in Sparta, married to Menelaus, and Prince Paris of Troy comes to call. Paris is so handsome that he is completely seductive to her. So, she goes off with the guest, the visitor of her husband, and she’s bowled over by him, and off they set to Troy, running away, leaving her daughter behind.

[00:23:00] She’s fallen helplessly in love with him, I think. Others say that, you know, it’s just forced on her by the gods. It’s a bit of both. And she then disappears to Troy, and she is caught in Troy. No more children, and she is increasingly, I think, lamenting her fate when the Iliad begins. Now, the Greeks mount an expedition to revenge, avenge the loss of Mendeleus, of his wife Helen.

[00:23:27] Who was stunningly beautiful, obviously fair haired, and so on. Homer gives us few, few details of her beauty. There’s just one wonderful comparison early on, where the old men of Troy are sitting near the battlements and chattering, and Helen passes by, veiled, and they say to one another, She looks remarkably like the immortal gods.

[00:23:52] It’s no shame to the Trojans and the Greeks to be suffering so much for a woman who looks like that. An amazingly oblique comment to her beauty. Now, Helen is a crucial foil to the heroes in the poem. To Paris, to Menelaus, and also her laments over the dead Hector, and so on. But her running away and her behavior are all in the past.

[00:24:17] They’ve all happened. We have speeches by her, a few, and they’re very, very striking. The last words, really, in the poem about how much she’s hated, um, in Troy, and only Priam and Hector have always had kind words for her. So her presence is very important in explaining the story. She can’t, of course, participate in the battle, because women don’t, but she’s there as a foil to remind us of a different world, that she is now regretting, the world of marital loyalty and fidelity, that she has betrayed, and Paris turns out to be Ever seductive, but really rather a bounder, as we would say in English.

[00:24:57] She’s boastful and very handsome, but was it really worth it, she begins to wonder. Homer gives her these supremely wonderful words when she refers to looking from the battlements and seeing in the distance Greek members of her previous family. She says in the old days, I pot a’en gi, and I translate that as almost everybody does.

[00:25:22] If it was ever really so. What an amazing feat of self awareness. Look, we’re in, according to me, in the 8th century BC, and here is a character in a main epic poem which is about a war reflecting a woman. God, was I really ever, was it really like that in my previous life? Almost everybody listening will know this as they get older.

[00:25:43] You look back and think, God, was that really me? And it’s there already in Homer, used so sparingly with such Pathos. So Helen initiates nothing, but she is there as a foil to so much.

[00:25:58] Helen Baxendale: Professor, thank you. So evocative. You were talking earlier about the capriciousness of the gods and their, their randomness.

[00:26:06] And I wondered if you could expand a little bit about what we ought to know about Achilles, Odysseus, Hector, Paris, Helen, and others, and how they’re guided by the active presence of the various Greek gods and goddesses.

[00:26:19] Robin Lane Fox: Yeah, absolutely. I’ll do that with pleasure. In the Odyssey, slightly different, possibly I think by the same poet, but later, it’s definitely aware of the Iliad.

[00:26:28] The great story of Odysseus home for Troy. Athena, the goddess, is Odysseus constant guard. and presence on his way home. And certainly Athena is there to assist Dissus, the gods have favorites, but it’s certainly thou. She also assists Achilles. She does so, partly out of favor for them, but mainly because having been slighted in the beauty contest, the apple of discord you just described, she is fanatically against Trojans.

[00:27:00] And on the other side, Apollo, who is siding with the Trojans. Is there to protect Hector? Interestingly, the hero Ajax, the ancients noticed this, has no personal divine protector unlike the others. Now, I’m going to dramatize this through one of the most overwhelming episodes. I do hope people will look at it and read it.

[00:27:21] In book 22, Achilles, who is taking revenge for Patroklos, has killed many of the Trojans, blaming them for Patroklos’s death, and he’s heading to the city of Troy. And Hector is alone, outside the gates, unable to face going inside, and be reproached by the Trojans for not having withdrawn earlier. And he wonders what to do.

[00:27:46] And he thinks, shall I go to him and plead with him? No, he’ll never listen. And then his nerve breaks. And he runs away from the city of Troy and Achilles pursues him. It’s a phenomenal scene compared rather like the scene Homer says in a dream. Can you imagine this? Where somebody seems endlessly to be chasing the dreamer and never catching him like a nightmare.

[00:28:10] We know these nightmares. We still have them for God’s sake. Two and a half thousand years later. Right. And then Hector has to stand to face Achilles. Before he does so, Athena, who is opposed to the Trojans and is going to help Achilles, is allowed to come down, despite Apollo’s help, and Zeus has decided that for Hector this will be the end.

[00:28:35] And it’s Utterly agonizing. She takes on the personage in disguise of what seems to be Hector’s brother, his great friend and supporter, Deiphobus. And Hector stands, and he thinks, I’m not alone. There’s a second person. with me. And he thanks what he thinks is Deiphobus. He throws a spear at Achilles, who throws another one at him.

[00:29:02] Both of them miss, and then Hector can turn, as Achilles can’t, to what he thinks is Deiphobus, to ask for a second spear. And all Homer says so unbelievably partly, but he was nowhere near. And Hector realizes that his time has come. He’s been deceived by a goddess. It was not Deaphobus at all. It was, in fact, somebody come to deceive him, Athena.

[00:29:33] And he must now face Achilles alone, with no spear as a weapon. And that is us playing out of this constant theme of the irony of ignorance, when suddenly mortals realize, oh my god, Now I understand. And then Achilles charges at him and spears him through his throat and Hector is then left stretched in the dust, dying.

[00:29:59] Now that is a very powerful and cruel ending and it is a dramatization of what Homer so often returns to. A feeling that we all have in life. Now I realize. Oh, I see. I didn’t know that he or she was actually all the while in love with my best friend. It’s suddenly clear to me. Or, I never realized that actually she was cheating, putting all the money in somebody else’s hands.

[00:30:31] Or, I hope that’s never happened to people, either of those things. And we suddenly think, oh, Now it’s clear. Or they were only using me. And at the highest level between God and man, Homer plays on this sudden, awful moment of awareness. But he does it so specially. We are privileged to hear, in his own words, the discussions of the gods.

[00:30:53] So we know what they’re going to do, and what they think. Before the heroes know, and then so poignantly, we watch them battling on to do their best. Hector’s death is an example, even though their beliefs are totally mistaken. And then the moment of truth, as we say, comes, and it is. Overwhelming.

[00:31:16] Alisha Searcy: I want to talk more about that.

[00:31:18] The Trojan Prince Hector kills Patroclus, the compatriot of the Greek warrior Achilles, as you said, and this event sets in motion Achilles showdown battle with Hector. Can you talk about his relationship with Patroclus? How Achilles dispute with Agamemnon sets up Patroclus death and how this drives Achilles wrath against Hector?

[00:31:39] Robin Lane Fox: Achilles and Patroklos. Achilles is older, and they are immensely close. Homer doesn’t go into the question of whether or not they’ve had sex together. That’s not the point. They have a tremendous love, a love as the Bible says, probably surpassing the love of women. We see them each in bed with other women in their tent, but that could involve anything.

[00:32:00] They could have been in bed with each other for all we know. That’s not the point. His love for Patroklos is overriding. So, so strong. And Patroklos sees. The Greek army being very hard pressed, even the doctors have been wounded, and he goes to Achilles and he begs to be allowed to go into battle dressed in Achilles armor and push the Trojans back.

[00:32:25] And Achilles allows him. A fatal decision, but tells him, don’t go too far, don’t try and capture Troy, you and I must eventually one day do that together, winning honor for me. But Patroklos fights on, and is so successful, and tries to assault the battlements of Troy, where the god Apollo defending Troy.

[00:32:46] pushes him back, and Patroclus falls, and Hector is the second hero, but the one who delivers the fatal blow to kill Patroclus, and then strips him of his armor. And the news comes to Achilles, who then, in a fit of revenge and changing rage, no longer against Agamemnon, but against Hector, who has been the one who killed the dearest man to him in the world.

[00:33:13] He goes out to war armed with the special armor, wonderful that the gods have prepared for him. We have this wonderful description of the heavenly shield that’s made for him with all the scenes of another world, a world often of peace and weddings and feasting and fun that is going to be left behind in the battle.

[00:33:34] It’s that is on Achilles arm, even as he goes into war. And he kills every Trojan in sight. He’s running amok, as we would say. And then Hector is waiting for him. So that’s how it all builds up. And then he takes Hector’s body and in rage, he drags it dead behind his chariot and mutilates the corpse. But then he’s told by the gods, No, stop it.

[00:33:58] You must allow it to be restored. You will receive great gifts. Give our body back. So we’re left wondering what will happen. And then we see what’s going to happen. Amazingly, Hector’s old father, King Priam, the King of Troy, whose son so many of them have been killed in earlier battles by Achilles, horrifies his wife and his remaining family by saying, I’m going out.

[00:34:25] I want to cradle the head of my dead son in my arms. I’m going to go out to Achilles with gifts. And if I die, I die. But at least I may be able to hold my son for the last time. Oh God. And off he goes, but he meets a God on the way whom he mistakes for a young man. It’s so wonderful, pleasant irony. And it’s the God Hermes who guides him into Achilles camp.

[00:34:54] And I’m going to wait there because it’s the bit of the book I’ll read at the end. Anything we feel might have happened, and yet what does happen inside Achilles tent is so overwhelming and so powerful that I think I may even cry on the telephone when trying to read it to you. That’s the power of the story.

[00:35:15] Nothing really happens really except what has been prearranged by the gods. And yet we read on fascinated to watch it happening through the eyes of heroes who don’t know that it’s prearranged. And hence the poem’s incredible power, what the great C. S. Lewis wonderfully called It’s Ruthless Poignancy.

[00:35:38] Please, please, all of you read it. Preferably learn Greek and read it, but if not, the excellent translation of Richmond Latimore, that’s the one. And remember Ruthless Poignancy. And part of it is the pervasive irony that we know. though they don’t, how life is going to turn out. And that’s still the case.

[00:36:03] Helen Baxendale: Professor, thank you. You anticipated my next question a little bit and ruminated beautifully on the scene of Hector’s death and then what transpires afterwards, but I wondered if you could tell us a little bit more about perhaps one of the most heart wrenching scenes of many in the Iliad. where Hector has an exchange with his wife, and before his fateful battle, because I think that’s a wonderful bit of foreshadowing, and I’d love to hear you tell us more about that.

[00:36:30] Robin Lane Fox: Well, I begin it by saying I encountered this at the age of 13. I was covered in earth, I was enjoying football. The way English people do, and it absolutely transfixed me, as it will transfix all of you. The Greeks are pressing so hard that Hector has gone back to Troy to get the women to pray to the goddess Athena.

[00:36:51] Note, we know that he doesn’t. that she’s actually favoring the Greeks. And he goes from household to household, and then he goes to look for his wife and their little son, their baby boy. And they’re not there because his wife, Andromache, has run out to the battlements to see what happens. So Hector goes out to find her, and she, with the nurse carrying the child, comes running to meet him.

[00:37:16] And she pleads with him to stay, she just thinks that he should stay in because there’s a dangerous point in the defense is this is a trick to try to make Hector stay inside of the city, and then he replies to her magnificently that he can’t, out of shame he must go. Go and defend the women and men of Troy, and though in his heart he knows that the day will come when Troy will fall, and then his wife Andromache will be hauled away into slavery.

[00:37:48] And he prays, May the earth lie heaped above me before I hear you cry or see you dragged away. And he reaches out after this amazing exchange, in itself overpowering, for his little boy. And the boy shrinks back into the bosom of his nurse, in terror at the waving plume of Hector’s military helmet. Gosh.

[00:38:14] So Hector takes it off and puts it on the ground and prays that the boy will grow up to delight his mother’s heart and killing a man in battle and so on, which is the way to delight a mother’s heart in this world. And then he hands the baby, which he’s been caressing back to Andromache, who is amazingly, in two words, Dacro and Gelisasa.

[00:38:41] laughing through her tears. Oh, good God. Even on the phone, it’s hard to describe this scene. That she’s laughing at the child’s reactions, but she’s weeping at what it means. And then she turns and they part. And she goes home and starts the lament for Hector already in his lifetime in his own household, knowing that he will never, ever come back for long to her from the war.

[00:39:11] What a parting. It brings out like nothing. All that is involved, the loss of a child, a baby, the love of Hector for her suddenly comes through. His fondness and love for his child and his son. And yet. It’s going to end in doom. Well, this has transfixed so, so many people. I give one example in antiquity.

[00:39:34] The daughter of a very, very strict Roman moralist, people may know Cato the Stoic, Pulsia, married Brutus. And Brutus, the murderer of Caesar, was setting off to go abroad from Italy. And she had to keep a stiff upper lip as he left. But she saw a painting. of this scene of Hector and Andromache’s farewell.

[00:39:59] This is a woman, unbelievably strong willed, who was prepared to eat burning coals later in her life, and yet she saw the picture, and she just wept and wept at the representation of it, and what it meant to her. I think we all know what Portia felt. It’s hundreds of words of exquisite beauty, speeches exchange, and Homer’s brilliant mastery of pathos.

[00:40:25] And the art, unlike me, of saying it all in so few words. It’s with us forever.

[00:40:35] Alisha Searcy: I want to ask, Professor, according to the legend, the Trojan Prince Paris killed Achilles by shooting him in the heel with an arrow. And Paris was avenging his brother, of course, Hector, whom Achilles slayed. And so though the death of Achilles is not described in the Iliad, his funeral is mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey.

[00:40:55] So can you talk to us about Homer’s story, narrative, and the continuity between the Iliad and the Odyssey?

[00:41:03] Robin Lane Fox: This is an excellent question. How much Homer is actually playing on the knowledge of what will come later. I mean, to give an example, the baby boy whom Hector holds and obviously adores and caresses in his hands and prays for.

[00:41:17] We know in later tradition, when the city of Troy falls several weeks later, will be thrown from the battlements and killed by the cruel Greeks. Homer never spells this out. How much he expected the audience to realize it and pick it up without being told. That is just a wonderfully open question. Now, what is important is some people say now that Homer really didn’t explore the terrible fate of women in the Trojan War in the Iliad.

[00:41:48] Well, of course he didn’t. The poem is not about the fall of the city. Women certainly make long speeches, including Achilles beloved slave concubine, Briseis, given back to him. She has a long speech. It’s not that there is a compulsory, what’s been called the silence of the girls, but Homer does not describe the fall of Troy.

[00:42:09] The poem ends with the funeral and the final feast on the Trojan side. In honor of Hector, whose body has been given back by Achilles. If Homer had written a poem directly about the fall of Troy, of course, we would have seen so much and heard so much of the terrible fates of the women involved. But in the Odyssey, we only really hear at all about any of this in flashback.

[00:42:37] When Odysseus, on his travels to get home, being defied by the god Poseidon and helped on by Athena with his long wanderings, all the wonderful stories in Neverland we know of all the various monsters he meets, the Cyclops and so forth. Once, Odysseus tells his past history. to a king who entertains him.

[00:42:57] So it comes in obliquely. Of course, Homer will have known the sequel very well. But the amazing thing about the Iliad is that he, I like to think, for the first time ever gave a long narrative poem. A single unified plot, the WR of Achilles, the loss engendered his revenge and his relenting crammed into events of, well, you know, 19 days.

[00:43:27] Amazing. Nobody’s ever done this, and it’s the plot, but made the narrative into an epic. So of course, he didn’t discuss the later stages of the Trojan War. It wasn’t that kind of a poem. The oddity is well aware of them, and if he had. The scenes of the Fall of Troy would be so poignant, unbelievable, as it is we now instead read Virgil.

[00:43:51] Helen Baxendale: Professor, thank you. This has been riveting. I wondered if you could close us out by reading a short passage from your book on the Iliad. And before you do, I wonder if you could tell us why you chose this passage and what enduring lessons we might draw from homozyliad and epic poetry from antiquity for contemporary listeners like us today.

[00:44:15] Robin Lane Fox: I think I would say the fact that there is a shared humanity. Even uniting enemies, they are men too, even if they are North Korean mercenaries fighting in Ukraine. They are fellow humans in home as I, and we are all born by shared humanity, and we are at the mercy. of sometimes unpredictable, favorable, and then deeply unfavorable gods who are more concerned with their own happiness than with ours.

[00:44:48] And there is a terrible irony that if we know the will of the gods, we know what would happen. But we don’t, and so life and its goods and bads are unpredictable. So that is why I’m going to choose a passage I have dwelt on, how could I not, the end of the Iliad. And I have said at one point, behind this extraordinary book, as we’ve divided the poem into books, is the last 500 lines.

[00:45:14] I can hear the weeping of the audiences who first listened to it in oral performance composed by Homer as he went along. And this version, I think, dictated to an early scribe who took it down. That, of course, is always a hypothesis. Okay. Priam enters Achilles room. To Achilles, old Priam, he must remember, elderly and alone.

[00:45:39] To Achilles utter amazement. In a scene of transcendental power, he falls before him as an abject suppliant and grasps his knees. But he also does something else. He kisses Achilles hands, those terrible manslaying hands, I quote, which had killed his many sons. He then begs Achilles to remember. But he, too, has a father, a father as old as I am, says Priam, still at home, with no one to keep off disaster, but alive and hoping daily to see you, Achilles, returning from Troy.

[00:46:21] But then he concludes, I am more pitiable still, as I have dared to do what no other mortal on Earth has ever dared, is to stretch to my lips the hand of the man who was killed. My son. Now, Homer doesn’t deploy irony here. Priam has chosen knowingly to humble himself to the utmost degree, and he shares the pathos here as knowingly as we do.

[00:46:51] Anything might have happened next within the general framework previously outlined by the gods, but Homer excels all expectations. Elderly Priam, he says, I quote, stirred in Achilles the desire to weep for his own father. And so he pushes old Priam away, I quote. Gently and the two of them weep together.

[00:47:19] Priam for his son Hector, the flare of men, Achilles now for his own father at home. And then again for Petrolos. I mean, imagine a meeting between Zelensky and Putin. I, it, it’s not a bad, modern analogy of how different and hard we are, but Homer is saying that despite the. Terrors of this war more in a shared humanity, united, two of the main protagonists, the king of the city alone in enemy camp.

[00:47:56] He could have been taken and killed and the leading hero of the army trying to sack the city. Ah, I won’t go on. The book continues at that overwhelming level in a way that is just a wonder, but such an example. to us all. Homer, like Greeks in general, is prepared to think that foreigners may be more like us, even perhaps than in life the Trojans really were.

[00:48:27] Ah, and it catches us in these extreme circumstances. And please, please read the poem. You will never forget it. Above all, go and learn Homeric Greek. It takes two years, no more. Get a Homeric dictionary. Don’t buy a translation of the poem. They give you about 5 percent of it. And then read it through. And I say what I always believe.

[00:48:54] If you do, you have not lived in vain. Wow.

[00:49:00] Alisha Searcy: Professor Robin Lane Fox, thank you for being with us today. Thank you for having me. What an honor.

[00:49:21] All right, what a great interview. What’d you think, Helen?

[00:49:25] Helen Baxendale: Fantastic. Super engaging. And of course I’m partial to any kind of classical material as a classical liberal arts. So this has been fun. Thanks for having me, Alisha.

[00:49:36] Alisha Searcy: I figured it would be right up your alley. So I’m so glad that you joined me before we go though.

[00:49:40] I’ve got to do the tweet of the week. This week, it comes from education week. And the title is the 10 most requested AP exams of 2024. I think we could probably guess what some of those are, but I’ll give you a little hint. Number 10 on the list was AP statistics. I didn’t take that one. Number five was United States government and politics.

[00:50:04] And number one on the list, AP English language and composition. So make sure you check out that article again, Helen, thanks for co hosting with me. It’s been a pleasure to have you. And to our listeners, make sure you join us next week. We’ll have Trish Schreber senior fellow at Montana’s frontier Institute talking about school choice and charter schools in big sky country.

[00:50:26] See you soon. Hey, this is Alisha. Thank you for listening to the learning curve. If you’d like to support the podcast further, we invite you to donate at pioneerinstitute.org/donations.

In this week’s episode of The Learning Curve, co-hosts Alisha Searcy and Dr. Helen Baxendale interview Robin Lane Fox, distinguished classicist and Emeritus Fellow at Oxford. Prof. Lane Fox offers profound insights into Homer’s Iliad and its enduring significance. He explores the epic’s historical and literary context, from its roots in oral tradition to its lasting influence on Western culture. Additionally, he discusses key figures like Achilles, Hector, and Helen, the interplay between mortals and gods, and pivotal moments such as Patroclus’s death and Hector’s farewell. Lane Fox also examines the Iliad’s connection to the Odyssey and its timeless themes of heroism, fate, and war, making a compelling case for its relevance today. In closing, he reads a passage from the end of the Iliad.

Stories of the Week: Alisha analyzed an article from K-12 Dive on how Medicaid has been the third largest source of federal funding for public schools; and Helen discussed a piece in Chalkbeat on how teaching English has slipped away from exploring literature.

Guest:

Robin Lane Fox, FRSL, is Emeritus Fellow of New College, Oxford and Reader in Ancient History, University of Oxford. He is the author of Alexander the Great (1973), Pagans and Christians (1986), The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand (2004), The Classical World (2005), Travelling Heroes: Greeks and Their Myths in the Epic Age of Homer (2008), and Augustine: Conversions to Confessions (2015), which won the Wolfson Prize for History. According to The Spectator (UK) his Homer and His Iliad (2023) is “The product of a lifetime’s contemplation of study… a stirring introduction to the sometimes alien Homeric world.” Lane Fox was educated at Eton College and he studied Classics at Magdalen College, Oxford University.

Robin Lane Fox, FRSL, is Emeritus Fellow of New College, Oxford and Reader in Ancient History, University of Oxford. He is the author of Alexander the Great (1973), Pagans and Christians (1986), The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand (2004), The Classical World (2005), Travelling Heroes: Greeks and Their Myths in the Epic Age of Homer (2008), and Augustine: Conversions to Confessions (2015), which won the Wolfson Prize for History. According to The Spectator (UK) his Homer and His Iliad (2023) is “The product of a lifetime’s contemplation of study… a stirring introduction to the sometimes alien Homeric world.” Lane Fox was educated at Eton College and he studied Classics at Magdalen College, Oxford University.