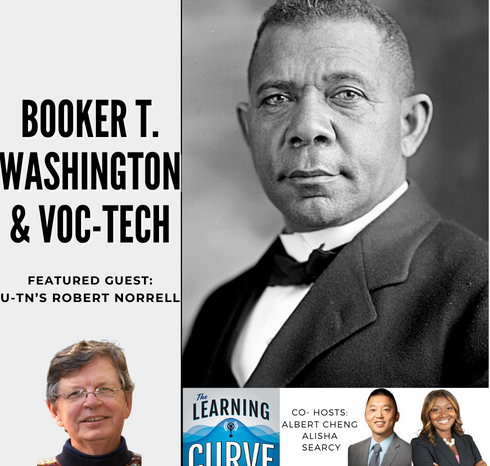

U-TN’s Robert Norrell on Booker T. Washington & Voc-Tech

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

[00:00:22] Albert Cheng: Well, hello everybody. It’s nice to be back here with you all on a new episode of The Learning Curve podcast. I’m your host this week, Dr. Albert Cheng from the University of Arkansas, and co-hosting with me is Alisha Searcy. Hey Alisha, how’s it going?

[00:00:38] Alisha Searcy: I am well, professor. Welcome back. How are you?

[00:00:40] Albert Cheng: Doing well, I’m excited for this show. I mean, we’ve got Professor Robert Norrell, who’s going to join us later to talk about Booker T. Washington. So, I’m really looking forward to learning from him. Very excited. So, let’s get to the news, Alisha. What I wanted to highlight this week was an article from Forbes pointing us to three legislative trends to look out for this year.

[00:01:00] I know, I think maybe a few weeks back, we talked about what education trends might hold for this year, but here we have another article. It’s only February, so I think this is early enough to talk about this kind of stuff. So, at Forbes, there’s an article that was highlighting three trends related to college and career readiness, really.

[00:01:18] And so I just really encourage listeners to read up on this. One’s about a lot of CTE, career technical education reforms, that are underway in various states. states are really rethinking how they prepare their students for post-graduation, post high school graduation. And then, another trend that was being pointed out is, on a related note, higher education trying to tie down their investments to the unique and particular economic development priorities within their states.

[00:01:48] States that can probably contribute in a particular industry, they’re thinking about, well, how do we invest so that our students can hang around and contribute to what we might offer to folks here at home and in our communities. And third, there’s some push in some states too. Try to put some more metrics on estimating the value of higher education.

[00:02:09] I know the value of higher ed these days is being questioned a lot for a variety of reasons. But yeah, I don’t know, some of these new efforts to put some metrics to measure the quality, to measure the value of higher ed. Hopefully I’ll do something to that. But anyway, I have no idea how any of these legislative pushes are going to unfold but it will be interesting to keep an eye out for some of these trends.

[00:02:31] Alisha Searcy: For sure. It’s interesting you mentioned legislative trends. The article that I came across was from The Hill, and it’s called America’s Facing a STEM and Data Education Crisis. And so, it talks about, of course, our math scores among teenagers in particular, 15-year-olds, have the lowest math scores that we’ve seen since the seventies.

[00:02:55] And of course we know COVID has something to do with that, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. And so, the concern here in the article is around STEM in particular and how data education, data literacy is sort of at crisis level and that although we don’t feel the effects right now, it really could harm us in the future. And they see this as a real crisis. And so, it’s interesting because, when you think about our education system and what it’s designed to do, right, we have to ask ourselves, what are we preparing our kids for? And so, one of the things the article points out is that the Society of Human Resources Management says the country has a need to boost STEM education because we’ll have nearly 3.5 million STEM jobs that need to be staffed by 2025. That’s huge. And so, as an example, they talk about operations research. One of the fastest growing STEM fields and so it allows students to have the data skills to save lives, save money, solve problems. A very interesting example is talking about how there’s an abundance of new applications of operations research — like humanitarian logistics or human trafficking and addressing the impact of things like COVID.

[00:04:11] And so here’s what I’ll just add to this. It didn’t talk about this, but I think that there are more factors that are contributing to the problem that we have in math and STEM in general. I would argue it’s the way that we’re teaching math. If you are a parent trying to help your kids at home, you know it’s very different than what we learned. And I’m not saying one way is better than the other, but I am saying that the way we’re teaching math I think could be a problem and something that needs to be looked at. And so just as we’re talking about the science of reading, who’s doing the research professor on the science of math, so that we can better teach our students.

[00:04:47] I also think that there’s this high focus on testing and skills and I’m not one of those people that’s anti-assessment. We have to know where our students are. But as a former superintendent, I know the pressure that I was under to make sure the kids are performing on a test. And it takes you away from teaching those critical thinking analysis type skills.

[00:05:08] And then I think the final contributor in my mind is that we need to do a better job overall in our education system of making learning more meaningful. Helping students make connections to the real world. And I don’t want to be offensive, but I will say that there are some things that I’ve learned and math, maybe some other subjects that I never used again, but what if we were teaching things like data science, and we could make those connections to solve real world problems for students.

[00:05:38] And again, to the point about policy, apparently there’s the Mathematical and Statistical Modeling Education Act and the Data Science and Literacy Act that are pieces of legislation moving through Congress. And if enacted, would help modernize secondary mathematical and STEM education. And so it gives $10 million annually for schools at all levels, from pre K to college.

[00:06:04] Very powerful. Now, let’s be honest. $10 million is not a lot of money per year, right, when you think about all the schools that we have. But, I think it’s a good start. I think this article was very important to point out the challenges that we’re having in terms of math and STEM and what we can actually do to fix it so that we can avoid these crises and make sure that kids are prepared in our schools.

[00:06:24] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Yeah. That’s excellent commentary. And then anytime anyone wants to talk math, that’s definitely near and dear to my heart as a pure math major. And you asked about the science of teaching math. I’ll remind listeners that late last year, I did this a lot of episodes ago, but we had Professor Stigler on the show and that’s his expertise.

[00:06:43] And so yeah, go check out that conversation. I learned quite a bit about effective math instruction from that. But anyway, before you do that, stick around with us, because coming up after the break, we’re going to have Professor Robert Norell join us to talk about Booker T. Washington. So, stick around.

[00:07:13] Alisha Searcy: We’re honored to have on with us Professor Robert Norrell. Robert Norrell is Professor and Bernadotte Schmidt Chair of Excellence with the Department of History at the University of Tennessee. In 2015, Norell published Alex Haley and the Books That Changed a Nation. In 2009, his biography, Up from History, The Life of Booker T. Washington, was widely acclaimed. In 2005, he published a well-reviewed interpretive synthesis of race relations in the 20th century United States, The House I Live In, Race in American Century. And his book, Reaping the Whirlwind, The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee, won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award in 1986.

[00:07:53] He has published 10 other books on the history of the American South and is the author of 25 scholarly articles. Professor Norrell has given invited lectures at Heidelberg University, Oxford University, The University of Cambridge, the University of Tubingen, and several other universities. Welcome to the show, professor.

[00:08:13] Professor Norrell: Thank you very much.

[00:08:14] Alisha Searcy: So, my first question, Jason Reilly of the Wall Street Journal wrote that in Up from History, a compelling biography Robert J. Norell restores the wizard of Tuskegee to his rightful place in the black pantheon. Would you share with us a brief overview of who Booker T. Washington was, the touchstones of his life as an educator, and why you decided to write a biography about him?

[00:08:39] Professor Norrell: Booker T. Washington was the principal of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which he founded in 1831. And it had a very meager beginning, but he grew it into a really strong institution. One of the most important institutions of higher education for African Americans in the country by, say, 1900. Washington had been born in slavery and had gone to school at Hampton Institute in Virginia, where he lived, and, or nearby.

[00:09:20] He was born in Virginia and then moved to West Virginia. And Hampton was organized to provide an industrial education, and Washington was imbued with the correctness of an industrial education for the freed slave people, and he was asked to start a school in Alabama. He quickly showed a remarkable capacity for several things. One is organizing a complex enterprise, which was a college, and then funding it by essentially seeking gifts to support students who went there. And then by promoting his ideas about education for African Americans around the country, and by 1895, he had become arguably the most prominent African American and certainly the most articulate advocate for an industrial education.

[00:10:29] Alisha Searcy: So, I want to go back for a moment, because as you noted, he was born an enslaved person, in 1856 in Virginia, which is unimaginable, to Jane, an enslaved African American woman on a plantation. And it’s noted that he never knew his birth date or his father, who was said to be a white man who resided on a neighboring plantation. Can you talk about Booker T. Washington’s early life as an enslaved person and his liberation after the Civil War?

[00:10:59] Professor Norrell: Well, he lived in slavery for a relatively short time. He mostly learned about it through his mother, who, by all accounts, was a quite remarkable woman, and he was very devoted to her. He didn’t recount any experiences of cruelty that he might have felt as an enslaved person, although he was at close hand enough to have seen the inherent cruelty of slavery. And the unknown white father was probably known to him. He never avowed who it was, but he in all likelihood knew. Certainly Jane would have known who his father was, but his position was that it never made any political sense for him to identify the man who probably was his father. There’s evidence from family correspondence that his brother, John, knew who the father was, but Booker Washington was remarkably comfortable with his identity as both an enslaved person and a person whose father was at least unidentified. He acted with confidence, with self-assurance, of a person who might have been born with a silver spoon in his mouth. So, I always found that a very attractive character in Washington — was his self-confidence.

[00:12:31] Alisha Searcy: Thank you, I never heard that. So, Booker T. Washington is quoted as saying: “We worshiped books. We wanted books. More books. The larger the books were, the better we liked them. We thought the mere possession and the mere handling, and the mere worship of books was going in some inexplicable way to make great and strong and useful men of our race.” Can you talk about Mr. Washington’s formative education, his experiences at Hampton Institute, a school, as you mentioned, established in Virginia to educate freedmen and their descendants, and his most important intellectual influences?

[00:13:10] Professor Norrell: Yeah, Washington was, to write that quote about we loved all books, realized that reading and education set you apart in American society and put you on the road to success. And that was something that all African Americans, he believed, should pursue. Before I get to Hampton, it’s important to emphasize he worked as the house boy to a white lady in West Virginia who hired him and then — she was not from there, she was from the [inaudible] and she made Booker Washington her special project to teach him how to be a good student, to teach him especially use of the language, the basic skills of mathematics, and so forth.

[00:14:01] And he proved to be every bit worthy of her attention. Then he went to Hampton and came under the tutelage of Samuel Armstrong, and Armstrong was a great role model, Civil War general, who had a very clear image, vision about what industrial education was, how it was appropriate for African Americans.

[00:14:30] Alisha Searcy: And so, thank you for mentioning that. I was going to ask you to talk more about Tuskegee. And so, we know that in 1881, the Hampton Institute president, General Samuel C. Armstrong actually recommended Booker T. Washington, then age 25, to become the first leader of Tuskegee Institute. And so, can you talk about, give us perhaps a thumbnail sketch of Tuskegee, its students, campus and buildings? The vocational tech philosophy, as well as how Mr. Washington’s leadership and fundraising transformed it in the face of Jim Crow racism and hostility in Alabama.

[00:15:07] Professor Norrell: Ooh, that’s a big question. A lot of different parts to it. Well, Tuskegee was a poor black belt town in the south that had lost the Civil War. Most of its wealth had been essentially destroyed by the emancipation of the slaves. So, it was a place that was struggling economically and to some extent racially in southern Alabama. But some black people there told whites that what they really wanted was a school. They wanted education for their children.

[00:15:44] And some people in Tuskegee then contacted General Armstrong, who told them about Booker Washington. They originally asked for a white man, and he said, well, I don’t have any white men, but I have a very capable colored fellow. And he sent Washington, and Washington was very energetic, very shrewd. He was selfless in terms of his willingness to work as long as necessary to try and succeed there, and he did succeed, recruiting initially mostly students from the neighborhood of Tuskegee, and eventually becoming a school that attracted African Americans from further beyond.

[00:16:28] He assumed that nobody who would want to come there had the wherewithal to pay for their own education, and he set out to essentially raise through donations of people, mostly in the north, Tuskegee, to finance the teaching of students in the building of the university. He built, between 1881 and 1900, the magnificent physical plant of nine buildings to house the educational program of Tuskegee, including both its industrial, vocational education, and its classical education as well, that is the academic subjects. And he never separated them or tried to segregate the two kinds of education from one another. He always thought that a good education for an African American person required both.

[00:17:32] Alisha Searcy: It’s mind blowing to think that this was happening less than 20 years after the end of slavery, that he was able to do all of this. Thank you for that. So, my last question before I turn it over to the other professor with us is: Booker T. Washington dedicated his life to the relationship between education and racial uplift and considered education and economic independence as a solution to racial inequalities. Can you summarize for us, and you talked a little bit about this, but his vocational tech industrial education mission and its role in addressing racial divides in America?

[00:18:10] Professor Norrell: Well, I suppose that Washington I believe that for the racial divide in the United States to be bridged, African Americans had to rise above the status of essentially a free slave. That they had to become economically independent, they had to become intellectually independent for there to be good relations between blacks and whites in America.

[00:18:42] And that was the point — very optimistic kind of presumption because as his life would show, he didn’t talk about it very much, but there was plenty of evidence that many whites, maybe most whites, did not want African Americans to rise above the condition of a sharecropper, a person dependent on whites, but that was his determination, and for a long, to a large extent, he promoted both his implementation at Tuskegee and then his implementation at satellite schools created by Tuskegee students around the South. And he campaigned for it in a kind of way to change the way Americans thought about blacks and their education by showing good examples of African American achievement in education.

[00:19:41] Albert Cheng: Thanks, Professor Norrell, for sharing that. And I want to continue exploring this topic of education as it relates to Washington’s work. So, in 1895 he gave the Atlanta Exposition address, which was viewed as a historic moment by African Americans and whites across the country. Could you tell our listeners about this speech, what was in it, how it was received, and how it became the foundation for Washington’s most vocal critics, which include the great Black intellectual, W.E.B. Du Bois?

[00:20:11] Professor Norrell: Well, Washington was asked to give the speech at what was effectively an industrial fair in Atlanta, and he was asked to do that because he was a prominent person of the day, African American person of the day, and the Atlanta Exposition wanted a black person among them, among many others. And he was given the job, and by 1895, Washington had become an amazingly skillful orator. He spoke all the time to many groups, and had been since 1881, and he had acquired a facility for explaining his philosophy and his ambitions for African Americans that were he’d been voiced in a lot.

[00:21:02] Albert Cheng: Picking up on his philosophy, we get to this now well-known debate between Washington and Du Bois. They both had different strategies for racial uplift as they actively competed for support within the black community. And we know that Washington favored the voke-tech industrial education, at least, going down that road, using that strategy, as you’ve been discussing, while Du Bois wanted blacks to have a classical liberal arts education. So, can you discuss this larger public intellectual debate, as well as just the relationship between Du Bois and Washington?

[00:21:39] Professor Norrell: Du Bois and Washington, or at least Du Bois, I think, read more into the differences between them than actually existed, at least that’s my argument. But Washington was for education for black people, full stop. And he was for vocational education, he was for then mostly called industrial education, but he was also for classical education. Students at Tuskegee took the academic subjects for about half their courses. And so, he never advocated ignoring literature and philosophy and all that, languages. He was all for them.

[00:22:23] He just said an African American should get as much education as he could put to good use. And he was skeptical about how many African Americans could put a classical education to good use, to remunerative use. Du Bois then, to contrast himself with Washington’s philosophy, insisted that classical education was more, more important.

[00:22:53] And Washington’s motivation for emphasizing vocational education and industrial education, which that was what benefactors would give money for. Benefactors, wealthy whites in the North were far less likely to give money to fund a department of philosophy or literature than they would to fund a school for skills.

[00:23:17] And, it was a practical matter for him. He had to be an advocate for that because that’s where his money was coming from. On the personal, they were friendly originally, and Washington offered Du Bois teaching jobs, and Du Bois did teach there on a temporary basis some, at Tuskegee. But Du Bois began to believe that Washington’s influence on African Americans at large in the United States was so great that it had become a kind of pernicious influence, and he became determined, especially encouraged by people like William Monroe Trotter in Boston, to disparage Washington, to criticize him, and to create, essentially, a challenge to Washington’s leadership of African Americans in about 1900, 1901.

[00:24:12] Albert Cheng: Well, speaking of 1901, that’s when U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt invited Washington to dine with him and his family at the White House. And then, mind you, that, as that was a time when segregation was the law. So certainly, the dinner between Washington and the president of the United States became a national controversy. Could you tell listeners about this episode? What was some of the media coverage and the politics around that moment?

[00:24:38] Professor Norrell: Well, it was highly sensationalized, and the fact that Washington had dinner with the president’s family at the White House, it was generally a breach of the racial etiquette of the time. Black people were not welcome to have social interactions with whites, but it’s also the very fact that the president of the United States — the most powerful position in American politics — was seeking the advice of a black man. Black men were in the minds of most whites, should not have that kind of influence, and Washington clearly did, and they set out to punish him. by disparaging him in his show of stories in the newspaper.

[00:25:26] Albert Cheng: Well, 1901’s also another significant year for Washington, because that’s when his famous book, Up From Slavery, was published. So, talk about this book. I mean, it describes his early life, his work establishing the Tuskegee Institute. Yeah, what else is in this book, and how did this book in particular impact American education?

[00:25:45] Professor Norrell: Washington had a good story to tell about his life, and he told it several times. Up from Slavery was not his first autobiography, it was, I believe, his second, but it was one that he aims at white audiences, and because of the way, the style in which he tells his story, he acquired a wide following. He was instantly embraced by white Americans, told the story of overcoming hardship, and experiencing triumph in his own life that, or, success, that could make whites believe that African Americans in America had a possibility, an opportunity for a good life, and Washington was happy to encourage that, even if the kinds of success — for most African Americans — was really mythical. But Washington was a fellow who took the world as it came to him and tried to make the best of it. And he did, with the Tuskegee Institute and with his writing and with his speaking.

[00:27:06] Albert Cheng: Well, so really in particular since the 1960s, if we think of civil rights, the names Martin Luther King and Malcolm X come up and then we don’t really probably think of Washington first. But so, final question here, what would you say Washington’s legacy is and how should we remember him today?

[00:27:24] Professor Norrell: Well, I’m trying to answer that question and trying to come up with a different answer to that question from what was current through most of the 20th century. Booker Washington’s reputation really suffered after his death, and it suffered particularly in the 1960s, with the rise of people like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, who had completely different personal opinions to Washington’s. And the kind of behavior that was idolized in Martin Luther King and to some extent in Malcolm X was anathema to the behavior what we knew about Booker Washington. I chose to write this biography because I thought people had, a lot of historians had gone out of their way to misunderstand Washington, to take him entirely out of the context of his life, and thus disparage him and to make him the sort of polar opposite of Martin Luther King, or for that matter, Malcolm X.

[00:28:44] And I was determined to say, let me just go through this context and all the challenges that he faced and all the difficulties that he had in order to build something that African Americans should be proud of and point to as an achievement that they themselves had done. And to give Washington credit for having orchestrated that.

[00:29:12] Albert Cheng: Yeah. Well, Professor Norrell, I’d like to give you the last word by giving you an opportunity to read a passage from your biography. So, the floor is yours.

[00:29:24] Professor Norrell: Okay. I’m going to read a paragraph or two from the very end of my book, two short paragraphs that I think go about as well as I can and saying what I think the significance of Booker Washington was. And this comes after I’ve given a long account of how I think Washington was misrepresented by historians essentially after World War II, so I’m going to read it a little bit. There was a tragic dimension to Washington’s efforts to remake the black image in the American land. During his lifetime, the obstacles to that purpose were simply insurmountable, since efforts could not overcome the intense political and cultural authority of white nationalism. But neither did the efforts of the NAACP succeed in that regard until World War II, when the demands of defeating racist enemies sparked the rejection of racial stereotypes in American culture. The fact remains that Washington was the first to identify it as a necessary challenge, although it was left for others to meet it. Washington should receive credit for anticipating the modern world, in which image was more readily manipulated than reality. in which prophecies were often self-fulfilling and pessimism had little social utility, so largely overlooked his effort to sustain blacks’ morale. In a terrible time, must be counted among the most heroic efforts in American history, Booker T. Washington told his people that they would survive the dark present. And as far as possible, he showed them how to do so by building an institution that demonstrated blacks’ potential for success and autonomy, he gave them reasons to have faith in the future. Indeed, his life itself was an object lesson in progress, providing hope that black people could rise to something better.

[00:31:33] His determination to shape his own symbolism and that of blacks as a group should be marked as a shrewd and valiant effort to help his people survive. At many levels, he succeeded in his purpose, for indeed, they did move up from history, from a time of segregation and despair to a time when the promise of equality in American life became a real possibility.

[00:31:59] Albert Cheng: Thank you, Professor Norell, Professor of American History at the University of Tennessee and author of Up from History, The Life of Booker T. Washington. Professor, Fascinating interview. We’re glad to have you on.

[00:32:09] Alisha Searcy: Learned a lot. Thank you so much, Professor.

[00:32:27] Albert Cheng: Well, yeah, that was a fascinating interview. I’m glad to have been a part of that. Learned so much. Well, before we wrap up, now for the Tweet of the Week, which comes from our friends over at EdNext. It’s a tweet actually about an article entitled, Going School Shopping. And so, this is actually a little research article released by Doug Harris and Matt Larson, in which they examined family preferences for schools in New Orleans.

[00:32:53] And I think a lot of listeners will be familiar, but in case you’re not. New Orleans is one of these cities where it’s choice all around, one app system, charters, lots of private schools, private school voucher program there. So, check out that article, I think it may not surprise many folks, but good social science sometimes proves the obvious, but I do think it’s worth a read.

[00:33:14] I was struck at just the diversity of preferences that parents had where this for academic achievement, for, Different types of extracurricular activities, how they make these tradeoffs with transportation and distance, even a preference for childcare, which seemed to be pretty salient among lower income families.

[00:33:32] And so again, these results are probably what you might’ve expected, but check it out and I, I do think if you’re a school leader out there, read up on that and just, maybe even consider just how you might better serve. The families that are part of your school and maybe even the families that aren’t part of your school.

[00:33:48] Alisha Searcy: That’s a great tweet. And I think the bottom line is listen to parents, right? We know what we want. We know what we need for our kids.

[00:33:57] Albert Cheng: Well, hey, Alisha, thanks for co-hosting with me again on this week’s episode.

[00:34:01] Alisha Searcy: Thanks. It’s always great to be with you, Professor.

[00:34:04] Albert Cheng: Yup. And that’s it for today. Come back here next week. We’re going to have. Another guest, a special one, Eva Moskowitz, the CEO of Success Academy Charter Schools, an author of A Plus Parenting, The Surprisingly Fun Guide to Raising Surprisingly Smart Kids. So, join us next week, but until then. Have a great one.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Prof. Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas and Alisha Searcy interview University of Tennessee Prof. Robert Norrell. He explores Booker T. Washington’s early life in slavery, his transformative leadership at Tuskegee Institute amidst Jim Crow racism, and his advocacy for vocational education as a means for racial uplift. Prof. Norrell also discusses Washington’s 1901 autobiography, Up From Slavery; his controversial White House dinner with President Theodore Roosevelt; and his often overlooked legacy following the activism of the 1960s Civil Rights era. In closing, Prof. Norrell reads a passage from his book Up from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington.

Stories of the Week: Prof. Cheng discusses a Forbes article on education and workforce legislative trends for 2024; Alisha analyzes a story from The Hill on the crisis in STEM and data education.

Guest:

Robert Norrell is Professor and Bernadotte Schmitt Chair of Excellence with the Department of History at the University of Tennessee. In 2015, Norrell published Alex Haley and the Books that Changed a Nation. In 2009, his biography, Up from History: the Life of Booker T. Washington, was widely acclaimed. In 2005, he published a well-reviewed interpretive synthesis of race relations in the twentieth-century United States, The House I Live In: Race in the American Century, and his book Reaping the Whirlwind: The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award in 1986. He has published ten other books on the history of the American South and is the author of 25 scholarly articles. Professor Norrell has given invited lectures at Heidelberg University, Oxford University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Tübingen, and several other universities.

Robert Norrell is Professor and Bernadotte Schmitt Chair of Excellence with the Department of History at the University of Tennessee. In 2015, Norrell published Alex Haley and the Books that Changed a Nation. In 2009, his biography, Up from History: the Life of Booker T. Washington, was widely acclaimed. In 2005, he published a well-reviewed interpretive synthesis of race relations in the twentieth-century United States, The House I Live In: Race in the American Century, and his book Reaping the Whirlwind: The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award in 1986. He has published ten other books on the history of the American South and is the author of 25 scholarly articles. Professor Norrell has given invited lectures at Heidelberg University, Oxford University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Tübingen, and several other universities.

Tweet of the Week: