Stanford’s Pulitzer Winner Jack Rakove on American Independence

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast, Video - Education /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Jack Rakove

[00:00:00] Alisha Searcy: Well, hello and welcome to the Learning Curve podcast. I’m your co-host, Alisha Thomas. Searcy, and glad to be joined today by special guest, Kelley Brown. Kelley, welcome back.

[00:00:30] Kelley Brown: Thanks, Alisha. It’s awesome to be here.

[00:00:32] Alisha Searcy: Yes, it is. And I know you’ve been on a couple of times, but why don’t you remind folks who you are and what you do every day?

[00:00:39] Kelley Brown: Sure thing. I am a high school government and history teacher out in the western part of Massachusetts, and I also work on some history primary source-based curriculum, do some professional development for teachers about teaching using primary sources, and so. I just absolutely am so excited for today’s podcast.

[00:01:01] Alisha Searcy: Excellent. I’m sure you are. It’s gonna be a great conversation. Before we jump into that though, we always like to start our show with talking about news that’s happening out there during the week, and so I would love for you to start and tell us what’s in the news for you. What articles have you found?

[00:01:17] Kelley Brown: Well, you know, I teach civic education and I came across this news brief that really kind of piqued my interest. It’s on EdSource and it was about a poll that was done in California by the Public Policy Institute of California that said that 67% of Californians believe that preparing engaged citizens is a high priority for public schools.

[00:01:43] And while there were some notable differences, which I’ll get to in a second in terms of the ways in which people waited that. 67% is a pretty astonishing number of people who say that that is a huge priority. So that kind of caught my attention, even though it’s only one state. I can imagine that if we ask this question in a lot of other states, the answer would be really similar.

[00:02:06] There were some differences amongst party, so 72% of Democrats said it was a priority versus 57% of Republicans. There was also a difference between women and men. 70% of women prioritized it versus 63% of men, but notice all above 50%. So that’s a pretty big hit. The other thing I thought was interesting is parents in particular, so when they actually broke down the adults, parents were much more likely to say that their local schools were doing a good job at preparing students to become engaged citizens, while they also think it’s like a big priority.

[00:02:46] So I thought those were some interesting thoughts. It really brought me back to, as we get into our podcast today, and we’re thinking about 1776 and the big anniversary, how when John Adams wrote thoughts on government, he thought that civic education was gonna be so important to our republic. And he said something to the effect of, you know, no expense for this purpose would be thought extravagant because education was so important.

[00:03:14] So I think that’s where I’ll start today.

[00:03:17] Alisha Searcy: I love that, and I agree with you. I think that California is just one of many places where. Most adults believe that we should be preparing our students to be civically engaged and grounded, right? And who we are as a country and where we need to go and what those ideals are.

[00:03:34] We’ve talked about this, you know, before, and no matter what’s going on, no matter who’s in office, we need to make sure that people understand our foundation and our government and how it works. And so I think you’re right that it’s probably all of our states, hopefully, that have the same numbers. I do think it’s interesting though that parents think that schools are preparing our students.

[00:03:55] I’m not sure I’m one parent who believes that. I think we have a little bit more work to do and a lot of our states, so it’s interesting that they think that we are though.

[00:04:04] Kelley Brown: I agree with that and I can say as a teacher, I definitely take that charge on and say, I think we can always do better. In just a couple of things, they noted that were really important.

[00:04:14] Were like understanding the Constitution elections, right? How they work, how to find good information. And really being able to look at multiple viewpoints without necessarily getting too distracted or too emotional about things. So to me, those seem like places that we can do better at. And I say that from the teacher’s point of view.

[00:04:37] Alisha Searcy: Agreed. And I wish that all of America’s students could be in your class. Frankly, we need that. And so glad that you’re here and you’re doing that work every day. Thanks for that article. So I wanted to mention an article that I came across in Education Next, which Party really has the edge on education.

[00:04:55] And our listeners know that I used to work with Democrats for Education Reform. I’m not there anymore, but I’m still continuing to do work. To get elected officials, frankly elected, who will focus on education reform and transforming our public schools. And so this article was very interesting to me because one of the things it points out is that Democrats in particular have pretty much always had the lead when it comes to voters trust and who they believe would handle education issues better.

[00:05:27] And there was only a couple of times over history in the last 26 years to be exact, according to this article, that Republicans have tied or bested Democrats on education. And that happened in February of 2001, January, 2002. That was shortly after no Child Left Behind was signed into laws. I found that very interesting.

[00:05:48] April, 2022 in the wake of the widespread of COVID and due school closures. And during those times is when there was more of a gap. Other than that, Democrats have always emerged as the favored party when it comes to education. And so why is this important? Because of course, with the work that I do to get folks elected who’s in power matters?

[00:06:12] And I think what’s interesting about the time that Republicans had more favorability, specifically when you think about No Child Left Behind, there’s plenty of criticism for No Child Left Behind. But I think I would argue, and some would probably disagree with me, that it was probably the most sweeping education reform that we’ve seen maybe in our life in my lifetime.

[00:06:35] And again, whether you agree with all of its performance or not, that accountability piece for me was the most critical to really disaggregate, for example, in the data and see how students are performing. And so I could see why voters at that time felt like Republicans were. Better at handling education.

[00:06:53] And so I think what it really speaks to is voters wanna see big ideas, reform, change, transformation because they want our schools to work. And so I think this is a great place for. Both parties to compete, you know, come up with the best ideas for how we make this transformation. How do we best support teachers?

[00:07:14] How do we make sure that we’ve got the right laws in place? How do we make sure that we, I don’t know, I would agree on standards, some not, but what are those standards, even if it’s state by state, what are the things that we want students to know? How do we get that to them in terms of curriculum? And so I think this is an important article for education next to bring forth, because regardless of the party, we want both of them to compete and want them to have the voter’s trust and earn the voter’s trust when it comes to education.

[00:07:45] So, very interesting article. We don’t even have to get into the politics. It’s really about, you know, which party wants to win when it comes to doing what’s best for kids.

[00:07:54] Kelley Brown: Yeah, I think that’s really interesting and I think one keyword you said there was accountability, right? When I think of it from the teacher’s perspective, you know, how do we know that we’re actually reaching students and teaching students, and I think that can always bring us to better conversations and really help us understand better when there’s some measures of accountability.

[00:08:16] Alisha Searcy: Exactly. That’s something I feel very strongly about because as you know. Kelley across the country, accountability has really been watered down and sadly that’s a bipartisan effort. We want bipartisanship, but this is not on this when we talk about lowering the standards and even having the right assessments in place to even know how students are performing, so that amazing teachers like you can have that information to provide the supports that students need.

[00:08:46] So I think accountability is one of those things that we should be able to agree on. Not to diminish it, but to strengthen it and to make sure that, again, we know how students are performing. Yes, agreed. So more on that at another time. But thank you for your article. And I think it really just speaks to, again, this ongoing work of what needs to happen in our schools, whether it’s teaching more civic education and preparing our students to be prepared for the world and for them to be good citizens of this country, or whether it is making sure that we’ve got elected leaders who are focused on education and again, preparing them for their futures in this country and in the world.

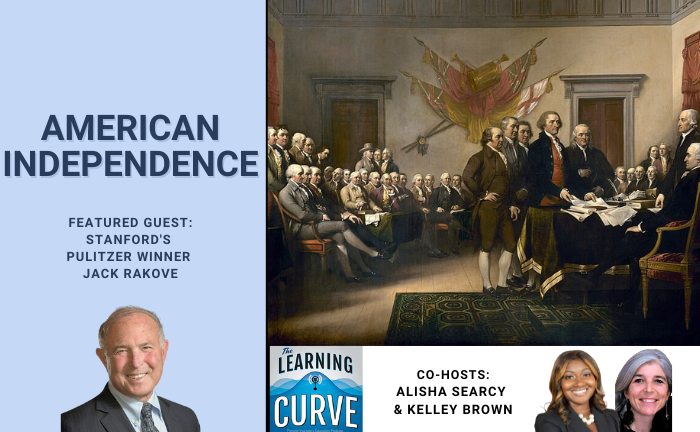

[00:09:26] So with that said, looking forward to today’s interview. We have Jack Rakove. He’s the co-pro professor of History and American Studies and Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Stanford University. We’ll be right back.

[00:09:53] Jack Rakove is Co-Pro Professor of History and American Studies and Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Stanford University. His principle areas of research include the origins of the American Revolution and Constitution, the political practice and theory of James Madison, and the role of historical knowledge in constitutional litigation.

[00:10:13] He’s the author of nine books, including Original Meanings, politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, which won the Pulitzer Prize in history. Revolutionaries a new history of the Invention of America, a politician thinking, the creative mind of James Madison and the Cambridge Companion to The Federalist.

[00:10:32] He earned an AB with honors and history from Haverford College and a PhD in history from Harvard University. Welcome to the show, professor. You Begin revolutionaries a new history of the Invention of America. With the young John Adams in 1756, a school teacher in Wooster, Massachusetts commenting about the composition of his classroom.

[00:10:56] Quote. In short, my little school, like The Great World, is made up of kings, politicians, divines, LLDs, fox, buffoons, fiddlers, psycho fence fools, Cox combs, chimney, sweepers, and every other character drawn in history or seen in the world. Is it not then the highest pleasure, my friend, to preside in this little world and quote Roe Adams.

[00:11:19] Would you briefly sketch for us the wider context of 18th century colonial Massachusetts before the American Revolution?

[00:11:27] Jack Rakove: Yeah. Well first off, I’d always loved that quotation, going back to the point where I first read it in the Early Diary of John Adams, and I was looking for a place to use it. So the point of using that quotation was to kind of set a sketch of what Provincial America was like before the period we called the Revolutionary Era erupted.

[00:11:45] And when you go on in that section of the book, there’s also little sketches about John Dickenson studying law in London at the ends of court, and then George Washington effectively launching what we call the French and Indian War, but it’s better known as Seven Years War. So the idea was to give some sense of the provincial identity of colonial Americans.

[00:12:03] Now among all the American provinces, the one that in a certain sense mattered most politically. Massachusetts, it was not the most important economically. The whole logic of the British Empire in the mid 18th century depended primarily on the commodity exporting plantation colonies of the South for Virginia down to the the New Colony of Georgia.

[00:12:25] The Northern colonies were interesting because the nature of the population somewhat different. They were consumer British imports, but politically, for a variety of reasons, Massachusetts had always been the most difficult to govern. And a lot of that goes back to its Milly Puritan origins during the great migration of, from 1630 to 1642.

[00:12:45] You know, Massachusetts had a homogeneous population. The bulk of the population in revolutionary Massachusetts was descended from the, uh, I guess 10,000 or so migrants who came to the New World between kind of late 16 29, 16 30, then 1642, which marked the beginning of the English Civil War and effectively ruptured the, the flow of migration.

[00:13:07] So Massachusetts had a, it had a homogeneous population. Second, it had its own political infrastructure. The form of town meetings, Massachusetts, and. Was the most highly mobilized in political terms, the most highly mobilized colony of the 13 mainland colonies, which formed the original federal union. So if awkward events were to take place, this happened later.

[00:13:31] Massachusetts, in a sense, was potentially the most volatile. And then for reasons I said, I suggested later it also, particularly the, let’s see, the period beginning with the stamp back crisis, it became particularly volatile, I think, in large measure because of the presence of Thomas Husson, the next to last royal governor of Massachusetts, who was in his own way, a very explosive personality.

[00:13:53] Kelley Brown: Previously, you’ve spoken about how the central problem that led to the American Revolution was a dispute about the nature of political authority within the British Empire. Could you talk about the British Parliament, the American colonies, and how the events of the mid 1760s and the legal debates about parliament legislating for the American colonies fueled the American Revolution?

[00:14:17] Jack Rakove: So I, I, I take you what, what’s sometimes called the rather old fashioned position that the American Revolution was distinctive because it didn’t spin out of a set of social grievances. It wasn’t a mass social upheaval. The way we think of, let’s say, the French Revolution or the Russian Revolution during certain sense, the Chinese Revolution and so on.

[00:14:36] It, it really did begin in a constitutional dispute, and the constitutional arguments were made sincerely on both sides. They were very powerful arguments on both sides. They were difficult to resolve for a variety of reasons, and in a certain sense, the inability to think about how to work out the constitutional dispute became a kind of a insuperable obstacle.

[00:14:58] Which produced the what? The situation I call the Crisis of Independence, the period from 1774 to 1776. And there were ways that some people felt you could, people like Benjamin Franklin, Edmund Burke and others realize you could solve the the problem of the Empire. But the constitutional orthodoxy on both sides was so deeply embedded that very few people were able to imagine how you could supersede it.

[00:15:21] So what’s the basic issue? Well, the basic issue was in the aftermath of the seven years war, for a variety of valid public policy reasons, the British government started rethinking its imperial policy in general, and it decided for a variety of reasons that the American, in a certain sense, would’ve been protected by the outcome of senators.

[00:15:39] War should contribute a bit more to the maintenance of the cost of empire. So that led to two tax measures. One was the Revenue Act of 1764. We sometimes called the Sugar Act, and the other was the Stamp Act of 1765. The Revenue Act of 1764 was not controversial in a certain sense because duties had always been levied on imports.

[00:16:01] British imports into the North American. So the Revenue Act of 7 64 revised those imports and the Americans had exceeded to those duties previously. They’d often evaded them. It’s pretty easy to smuggle goods into British North America. The East Coast is very different from the West coast. East Coast has all these estuaries and rivers, and it’s pretty hard of police though the whole, the whole East coast, the West coast actually is very different, but it doesn’t matter here.

[00:16:25] But the tax that really mattered was the Stamp Act of 1765, and that’s what Americans called a direct tax. It took the form of taxes on particular items and taxes on, on newspapers and taxes, on legal documents and so on. So the Americans argued, you know, principle deep, we rooted in Anglo-American Constitution history that taxes are the free gift of the people.

[00:16:48] And that to be valid, to be legitimate, they had to be approved by one’s duly elected representatives. There were no elected American members in the House of Commons that sat in Westminster in in London. For a variety of reasons. The Americans never really asked for, the British would never have granted an American representation.

[00:17:08] So the basic American argument was that because they were not represented in the House of Commons, they could not be made to pay the kind of direct taxes to the Stamp Act body. And those are pretty powerful arguments, and they’re pretty particularly powerful arguments because in 18th century Britain, you have a minuscule electorate.

[00:17:28] You probably like 10,000 voters, something like that. Choose the the 500 some members of the House of Commons. A lot of them are electorate from what are called rotten burs and pocket barrels. Rotten burs have few of any residents pocket boroughs or boroughs that are dominated by some dominant interest closely tied to the government.

[00:17:48] So the whole system is mal portioned by American standards, and it seems to be inequitable. So the Americans have very powerful arguments of representation that the ruling class of Britain doesn’t really wanna touch upon because it would open up. All these questions about inequity and representation of Britain, but the British had a powerful counterargument.

[00:18:06] The counterargument was that whatever you say about representation, in the end, from their perspective, there is no denying the proposition That parliament, which of course consists of two houses, the House of Commons, which represents the people, the of origins, which it doesn’t represent anyone. It just is the aristocracy along with the clergy.

[00:18:25] The, in the end, going back to the glorious revolution of 16 88, 16 89, in in English history, parliament had been recognized as the supreme sovereign source of law within Great Britain, and by extension within the British Empire as a whole. Then the doubt probably was sovereignty as people thought about in the 18th century, not as Americans would come to think about it.

[00:18:48] Sovereign was thought to be of an absolute irresistible, unitary nature, something you could not divide. It had to reside in some one place. The only place within the whole British scheme where it could reside was parliament or what’s called technically the king a parliament, because the king’s descent was needed for ary legislation to be valid.

[00:19:11] So the upshot of this was that the Americans watched a whole assistance campaign, they stopped importing British goods, they closed the courts. They effectively undermined royal government in British North America. And the, you know, the non deportation agreement weeds, uh, produced places a lot of economic pressure on Britain.

[00:19:28] So in March, 1766, parliament repealed the Stamp Act and, and repealed the Stamp Act, but also passed something called the Declaratory Act to Creditory Act Affirm, just as a matter of principle, not as a legislative program, but just as a matter of principle, that the American colonists were subject to the jurisdiction of parliament in all cases whatsoever.

[00:19:48] So the kinda act that they had to get through parliament. Because back benchers in the House of Commons would probably not have agreed to the repeal had they not reaffirmed that underlying principle of British sovereignty. So there’s a situation away. Then what happens? You have a second dispute in the rise in 1767 to get the repeal through the House of Commons.

[00:20:09] Benjamin Franklin, who had been living in London since 1755 and represented the Pennsylvania legislature and also the Massachusetts General Court, the Massachusetts legislature, Franklin testified in the House of Commons and he, he seemed to kind of introduce the kind of, I think for political reasons is kind of distinction.

[00:20:27] He says, well, what the only kind of taxation Americans were objecting to was direct taxation in the form of the stamp act. Indirect taxation was to take the form of duties on commerce. It’s not a tax that the government presents to you, it’s just something you pay in the ordinary course of purchasing goods.

[00:20:43] So it seems more innocuous. That was, okay. So in 70, 67 or Townsend, the chancellor, the ex checker. Says, well look, the Americans Franklin has made this distinction. Why don’t we just add additional duties on things the Americans import, things like we paint tea, a few other things, and we can derive some revenue the that way.

[00:21:05] So barman passes the town duties, took the Americans much longer to start organized resistance to the towns of duties in 17 67, 68, than it had to the Stamp Act. But eventually what happens is John Dickinson no writes these famous letters from a Pennsylvania farmer, which basically argues it’s not the character of the duty of the tax levied.

[00:21:27] It’s whether or not the tax is laid for purposes of revenue. If it’s a tax in that form, the form of the tax doesn’t matter if you know what its purpose is. So we know that from what the briers have said about it, that to raise revenue was the basis, the goal of the towns of duties. It’s a tax and it’s been enacted without our consent, and therefore we should resist that too.

[00:21:48] So the Americans took them longer, but finally they, they do get another non deportation agreement going. And British merchants of course start protesting about that ’cause American commerce is very important to their prosperity. And again, parliament. And I think, actually, I think it’s the same day the Boston Massacre Parliament repealed the town of duties, but it, it left one duty intact.

[00:22:09] The duty on T, which in sure sense, makes the same theoretical statement that the Declaratory Act had made back in 1766. It’s saying, we’re not pronouncing the power. The power still exists. And it is still an expression of parliamentary sovereignty. So they’re, but they’re the situation late. I think the next three years, the, what I call the fallow years in my first book, it’s actually very relative quiet.

[00:22:32] I think people on both sides understood that these were dangerous issues. If you really wanna preserve British Empire because it worked to the net benefit prosperity of all, shouldn’t have sweat. These issues, I think is Thomas Cushing this, speaking of Massachusetts General Court say, we should let these issues sleep.

[00:22:47] Just preserve the empire in other ways. But then what happens is, for other reasons, in the fall of 1773 to rescue the East Indie Company, which was a dominant economic presence in British life, it was going bankrupt to rescue the East Indie company Parliament, enact the Tea Act, which gives the East Company a monopoly.

[00:23:08] The sale of all legal tea in North America lowers the duty on tea, and the essentially, Americans will, they may have principles on one thing, but if you make it cheap enough, they’ll abandon their principles in order to get cheaper tea. And that of course, leads to the old crisis of the Boston Tea Party, which in turn led to the coercive acts.

[00:23:26] The House of Commons passes the set of acts, effectively punishing Massachusetts for the Tea Party. And then you get to the crisis of independence.

[00:23:33] Alisha Searcy: It’s perfect timing and first of all, it’s very interesting to learn the history as we talk about taxes and where we are now. But you mentioned the Boston Tea Party and you write in your book quote, but once the Mohawks numbering 15 or 20, a vessel boarded the ships.

[00:23:49] The crowd watched silently is 340 massive of East India AC company T were hauled on deck and whacked up with axes. Then the contents were dumped overboard. And you also go on to say that by 9:00 PM a cargo valued at a hefty 9,000 pounds sterling was weekly brewing in the low tide waters. Would you tell us more about the December 16th, 1773 Boston Tea Party and its role in inflaming great Britain’s colonial crisis in America?

[00:24:21] Jack Rakove: Well, the Boston Tea Party I think was the decisive. I think the term the stories would use the decisive precipitant, or you could say the trigger that in effect launches what I called earlier, the crisis of independence. You can ask a great question and, and I pursue this in my writing, had the Boston Party not happened, would we have evolved into another Canada, you know, kind of confederation of states or whatever, still bound to the, to the greater British empire?

[00:24:49] So the story I tell about the Boston Tea Party is that I think a lot of it really depended on a single person, Thomas Hutchinson, who was the next and last royal governor of Massachusetts. He was descendant from Anne Hutchinson, the famous Puritan radical so-called Antinomian from the first generation of Puritan Migrant of the great, great migration in the 1630s.

[00:25:12] Hutchinson was a man who had made his career. In effect as a servant of the empire. He was a merchant. As with the other members of his family, he would benefit, actually, his family would benefit from the importation Eastern company, gee. But he was also the object of massive opposition and resistance in Massachusetts.

[00:25:29] And what happened in 70 73? It’s a nursing story. Hutchinson opened the new year much as the king would open a session of parliament by delivering a speech to the Massachusetts Journal court, which made the argument that the Americans had to be prepared to accept a kind of secondary status within the British Empire.

[00:25:49] They could not insist on possessing all the rights of Englishmen either. It was in their interest to accept, I won’t say second class citizenship, but accept some relegation in their rights and privileges because the overall benefits of empire were so significant. It would be foolish to kind of throw them away over some abstract question or parliamentary jurisdiction.

[00:26:10] Hutchinson did this in his own initiative. I think he did in part because Samuel Adams and his buddies had had organized the Boston Committee, a correspondence back in the fall of 1772 when they were harassing Hutchinson on a variety of issues, including whether or not he should be paid a royal salary instead of being paid by salary levied by the general court.

[00:26:28] So Hutchinson, in fact, is trying to respond to Samuel Adams and his buddies and the Boston Committee correspondence. So delivers a speech and instead of it preaching common sense the people of Massachusetts, which is always a difficult task in any period, Hutchinson arou the general court to restate all the arguments.

[00:26:46] So all, all the issues have been disputed in the late 1760s in which I think the government of or North would’ve happy to keep asleep. Were now revived and people out the colony start reading about this. So that’s step number one. Step number two is Benjamin Franklin. Remember Franklin is in London.

[00:27:02] Still, he was quite happily living there. Franklin was a very Cobo person. Franklin got hold of a set of letters that Hutchinson had written to British correspondent, probably a guy named Thomas Ell, who was very active in Imperial Affairs. And he sent them back to Thomas Cushing, speaker, the Massachusetts General Court of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts Journal Court.

[00:27:23] And he said, you can read these but don’t publish them. And the reason he said them was it contained all these statements where Hutchinson says in the Q phrase, there must be some abridgement of British liberties. Again, this notion of Americans should accept some secondary status and citizenship because the net benefits Franklin, I think had decided that Hutchinson was, and I perhaps not incorrectly, that Hutchinson was a wild cannon, a loose cannon, and that to preserve the empire, which Franklin very much wanted to do.

[00:27:52] Franklin was not an enemy at the British. He, he felt the long-term advantages would reside the Americans, that the Americans should just buy their time. The more populous they got, the more prosperous they became, the better position they would be in. So Franklin felt you had to destroy Hutchinson politically.

[00:28:07] Of course the scandal goes up. The ministry could not abandon Hutchinson. You couldn’t kind of make him a political sacrifice. And then the next result is when the Boston Heat party is enacted, which no one expected. Very few, very few Americans paid much attention to it, pun Franklin was often wanted.

[00:28:22] So basically it’s enacted and then becomes the course of a new set of rounds of resistance. It gives the so-called radical leaders in Massachusetts get people like Samuel Adams in Boston, or Charles Thompson in Philadelphia, or the Lee Family of Virginia and so on and so on. It gives them a new basis for organizing resistance to what they felt was the long-term desire on the park British government to subordinate the American colonies.

[00:28:47] The key thing that happened is that once the, there are three T ships once they entered Boston Harbor, I guess at the very end of November. 70, 73 under British Imperial law, under the law regulating imperial commerce, which which was, so the department had, the Americans could see, department did have this authority to regulate imperial commerce.

[00:29:06] Once the cargo is legally entered to harbor, it has to be landed, the duties paid out, or else the cargo be confiscated. So Hutchinson, I think, welcomed a confrontation with the radicals. He felt he had the law on his side. He’d taken a couple lickings in a sense, earlier the year. I mean, the two prior episodes had not gone well for him.

[00:29:27] And I think now he felt with the law on his side, and of course with British troops and the British Navy around to help reinforce his position, he could go ahead and force a confrontation and come out on the other side. Royal officials elsewhere followed a different course facing protests. They allowed the T shifts to sail back to England with their cargoes and voted hutches and forced a confrontation.

[00:29:50] The Boston Tea Party was the result and the enactment of the coercive acts by Parliament in the winter and spring of 1774 was what provoked, you know, I’ve called the Crisis of Independence.

[00:30:02] Kelley Brown: If we take it from that point and kind of roll the ball forward a little bit in revolutionaries, you write quote on their own, Americans had created a new central political authority in the Continental Congress, which first met at Philadelphia in September of 1774 and was set to reconvene in May of 1775.

[00:30:23] Could you discuss a little bit, and I know we, we skipped maybe a middle part here, but can you discuss the development of the Continental Congress, its purpose for being formed? A few of its key leaders like John Adams, John Dickinson, Richard Henry Lee, and Thomas Jefferson, as well as how it became a model for colonial American self-government and ultimately a vehicle for delivering the Declaration of Independence.

[00:30:48] Jack Rakove: So where did the Boston Port Act, which was the first of the coercive acts passed to punish Massachusetts? Basically what it did was to close the Port of Boston until restitution was made for the tea that was destroyed. Or as I say, my book Brooded someone incorrectly brooded in Boston Harbor. So when word of the TX started reaching American Harbors in mid-May 1774, the Boston Radicals led by Samuel Adams and Cushing and the circle of leaders around them were beating, and the Virginia legislature was in session then, and leaders in other colonies start figuring out what to do.

[00:31:23] So basically what happened is, if you go back to spring 1770, when the towels of duties were repealed, collective American resistance had kind of fallen apart their networks of correspondence among the radical leaders. Again, you know, like people mentioned like Lee Family, the Adams is in Massachusetts and so on, but there’s no real apparatus.

[00:31:45] There’s no real infrastructure. When the news of the Port Act arrived, I think the Boston Rags proposed we should have an immediate suspension of commerce beginning in New England with Great Britain. But people elsewhere argue that this is a serious crisis, and the only way we can deal with it is we first need to form some kind of, uh, intercolonial infrastructure, if I could use that expression.

[00:32:10] Uh, we need to have some central agency to coordinate. Whatever measures we’re gonna adopt. Also to agree what are, what are the positions in terms of constitutional argument? What are our goals? What is the policy we wanna pursue? The only way we can do it is by having a joint consultation. There’ve been something like that.

[00:32:25] Back in August of 70 65, there was a setback congress in a initial, somewhat smaller antecedent of the first guy on Congress where 12 of the colonies ge, Georgia, which is kind of a distant frontier output. Georgia did not make it to Philadelphia in September 17th, 24, but all the other 12 colonies were there.

[00:32:45] So there’s a basic impetus to, uh, set up a kind of consultative body Congress. Now, when Americans use it, we assume it means a legislature, but when they use it in the 18th century, its connotation is more of a consultative body. It’s almost as a quasi diplomatic. Character. So they assembled in Philadelphia.

[00:33:06] I mean, I think, I think September 5th, 1774 was the day they first met. As soon as they met, there was the so-called powder alarm. There was rumor that hostilities were on the verge of breaking outta Massachusetts. They meet, if not in a panic, but there’s this kind of fire alarm that seems to go off. Turns out the rumors were false and, and not true, but it kind of energized the delegates at the very beginning.

[00:33:28] So they, they met essentially for about eight weeks. They adjourned in near the end of October, 1774, and they draft a petition to the crown. They’re not gonna petition parliament because they don’t recognize the parliament as any jurisdiction over the American of the Americans. They’re only gonna petition the King George II and his government.

[00:33:46] They usually address to the British people. They send an address off to Canada and they form something called the association, which effectively authorizes committees of inspection in every community across the counties to begin enforcing the non deportation agreement. Which they decided would be their first measure of, I can’t say forceful, of active resistance to British policy.

[00:34:09] Now, the Southern Americans going back the old technique of a commercial boycott, and they’re gonna wait to see what’s gonna happen. Now the important thing to note here is that right after Boston Party, I came over the second course of act, the Massachusetts Government Act came over, and that was, that was an attempt to alter by Act of Parliament, the second royal Charter of Massachusetts, which states 1691.

[00:34:30] 1692. And in addition, they, so it alters the structure of government. Massachusetts prohibits the town meetings for meeting more than once a year for the purpose of elected officials. So they won’t exist as a political infrastructure. They can organize the population and that kind of deepens the crisis.

[00:34:50] So in effect, what happens is in Massachusetts and other counties, royal government starts collapsing. We’ll go through this in all detail, but what defective, what the kind of Congress did was it needed some, some to rely on at the community level to make this system of non deportation work. And they should do it in a general way.

[00:35:12] They weren’t supposed to tarn feather people the way which had happened to a few stamp stamp collectors back in 1765, which was an awful process to have to experience. They’re supposed to really just bring a lot of community pressure to bear on people who are supporting royal policy, and then the upshot is you’re gonna wait to see what happens, whether or not the government’s gonna respond to it.

[00:35:32] What happened in Massachusetts was, in addition to changing the form of government Governor, the governor of War North replaced Thomas Hutchinson. They send General Thomas Gage with, you know, additional regiments of troops to Massachusetts. And he was supposed to try, he’s gonna, the new governor, in fact, he’s a military governor, but the legislature, general court’s not gonna listen to him.

[00:35:54] They form a, a provincial convention that got a surrogate legislature, which starts happening in other colonies because if you convene the colonial legislatures, if you, royal governor, if you allow the colonial legislatures to sit, they’re gonna support resistance. So most of the colonies you have to prevent legal government from operating.

[00:36:10] But the Americans are not gonna wiggle without some form of organized government. So they, they formed what we call extra legal institutions, conventions, and committees that have all the effective power of government. Royal Governors watch is happening and they say, in fact, we want to control the countryside.

[00:36:26] These institutions are just as powerful as the legal institutions, which preceded them. So you have the CEO potentially explosive situation in Massachusetts. Now, Boston at that time, it’s not like today, Boston Nation century still, there was no back bay. There was no landfill along the Charles River. It’s really a narrow peninsula, so it’s easy to cut off.

[00:36:46] Troops were kind of isolated there if they move on to the countryside. Massachusetts is probably the most densely settled community in all of North America. In all the militia companies are organizing and training, and it’s potentially in explosive situation. But the government wants Gage to restore royal rules, so they give them instruction.

[00:37:06] So in April, 1775, he’d sent a big contingent of forces out to Lexington and Concord. He wants to hopefully capture the two American leaders. Could be John Hancock and Samuel Adams, but also to seize the munitions that the Americans had been gathering at Concord, Massachusetts. Lexington was just a diversion.

[00:37:24] Concord was the main objective. The Americans turn out, there’s a, the exchange of fire to Lexington. I think 10 or 11 Americans were left dead, but that’s, that’s kinda minor. The real engagement took place at Concord. The Americans have their ranks, they exchange rounds. The British don’t have the numbers to overcome the Americans.

[00:37:41] The British start retreat back to Massachusetts and the Americans snipe them all the way back. Americans are kinda spread out along the road. The British are trying March formations, so the British are quite vulnerable. They take significant casualties. So when the second kind of Congress met in May 17, 75, war had already erupted and they had a very interesting debate and to be honest, and the only story I think was really fall closely what happened.

[00:38:04] They had an interesting debate. Took again, May 16th and May 23rd, kind of a week apart. They have to start organizing military resistance because wars erupted in June. George Washington’s appointed the commander in chief of what’s now not the Massachusetts provisional army, but the continental Army representing all 13 counties.

[00:38:22] But they have, they have a pretty extensive debate as to whether or not they’re gonna change the positions they’d adopt in 1774. And there was a group of moderates and John Dickinson, in many ways was the most important, who argued that even though the government largely ignored their petitions, and instead was relying on military force, not negotiation to, you know, continue to try to repress Massachusetts, Massachusetts and isolated from the other counties.

[00:38:50] A strategy that was obviously breaking down. Hutchinson, unu London quite well. He studied there and who was, in a sense, Hutchinson was kind of a lapsed Quaker. He came from Quaker roots. He’s, he married outside the faith and so he is somewhat isolated. But he was still in his moral convictions. He’s still, in many ways a Quaker, though he is not a pacifist, Hutchinson felt the Americans should take a more anti role.

[00:39:13] I mean, he said maybe we should send our own delegation off to London, negotiate, and maybe we should send another petition to the king to reaffirm our, our underlying loyalty to the empire. Insist that we want our rights to be redressed. They’re producing a lot, they produce a lot of pushback. And at one point Congress has a story meeting and a single delegate.

[00:39:32] The old delegate and Stein and connected delegates diary that half the members walked out. I mean, I think tempers got pretty inflamed at one point, but in the end, Congress did not. It was willing to restate its desire to have an accommodation, but it was not willing to alter its position. So that’s essentially what happened in the summer 1775.

[00:39:52] And then the question is both sides have basically reviewed the situation, not the one is willing to alter their position. So you go, you go on into the new year of 1776. And at that point, the Americans learned that the British had started negotiating treaties with various German principalities. You know, British, British need to enlarge their, their land forces.

[00:40:15] They need to recruit, in effect, mercenary armies to buttress their ranks in North America, the king to declare the Americans being a state of rebellion. They start closing American ports. They make American shipping overseas subject to seizure and confiscation both sides and effectively doubled down.

[00:40:32] And then of course, what happens is Thomas Payne publishes Common Sense, I think the first or second week of January, teenth 76, very early in the New Year. And common sense, it was a, a pamphlet with a kind of breathtaking literary success, really made a powerful case for independence. It also made a powerful den of monarchy.

[00:40:50] So it’s a Republican tract. It had a big impact on public opinion. And so now Congress started to move forward with the kind of agenda for independence. And uh, basically what happens in 1776 is it also happened back in 1774, white Spring and summer 74 communities around the country started adopting resolutions saying It’s time to move forward.

[00:41:12] There’s nothing we can owe for from Great Britain. It’s time for us to kind of move forward and start preparing to declare independence. So Congress is always waiting for public opinion to move ahead and, you know, so it’s important to understand that if you look at Congress, you do have kinda radical leaders like Samuel Samuel and John Adams from Massachusetts who were, who were distant cousins, and they’re not first or second cousins.

[00:41:34] They’re a few, few other degrees apart. The Lee family, Richard, Henry Lee, and Francis White Foot Lee from Virginia. Charles Thompson from Philadelphia. And then you have a group of delegates from the, the so-called middle colonies. People like James Wilson. Well, first of all, John Dickinson, who is really a true celebrity.

[00:41:53] Both people like John Jay, James Dwayne, Robert Morriss, governor Morris, James Wilson. These are the moderates. And I think their position was that if the British government had take the initiative of sending commissioners to North America and given those commissioners genuine authority to negotiate, then they would’ve sat them towards independence.

[00:42:18] Then you’d have negotiations. You’d try to work out some accommodation between what weren’t affect two countries that were, that were part of one empire. The problem was A, the British were slow to do it. B, they did not, you know, it was almost, it was difficult to, not impossible for the British to abandon their notion of primary sovereign.

[00:42:34] It was, it’s such a sacred part of British thinking that to abandon that is just adversely inconceivable. So then what happens? In early June, 1776, June 10th, the Virginians went by Richard Henry Lee, you know, with the ACT support of Thomas Jefferson, introduced a set of resolutions to draft out as a confederation and then stands, falls to John Dickinson and then to draft a declaration of amendment.

[00:42:59] So John Adams becomes the main guy in charge of drafting a plan of treaties, what we call the model treaty. Dickinson becomes the main guy drafting the articles confederation. He’s the chair of that committee, and Jefferson is getting, Jefferson was not an active speaker, but he was a great draftsman. So Jefferson becomes vie draftsman of the Declaration of Independence, which became at the end, the source of eternal fame.

[00:43:23] There’s a gap of a few weeks. I think most of the, the leaders were waiting for public opinion to rally around the cause. A couple colonies in New York seemed a little slow to move and so on. So there’s a bit of a gap, but the decision already been taken at that point. It’s just a matter of timing, and I think the key point to make here is decision making con Congress is always consensual in nature.

[00:43:46] It was never about one side getting the advantage over the other. The delegates realized that their own authority depended upon preserving, not just the facade, but really the substance of the kind of collective consensual decision making. And there was the secret of its power.

[00:44:00] Alisha Searcy: I wanna move to a dark part of history talking about slavery. And you say, how is it the celebrated English essayist and opponent of American Independence? Samuel Johnson asked at the start of the revolution that we hear the loudest Yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes. Would you talk about slavery within the British Empire and the Colonial America at the time of the revolution and the role that the slave trade played in the northern and southern colonial economies, as well as the role that slavery played within the Continental Congress in their internal politics?

[00:44:40] Jack Rakove: It’s important to know that when Anglo-Americans, Americans knew slavery in the 18th century, the word had two very different meanings. The familiar meaning the one we’re most familiar with, that we’re most, I won’t say comfortable, but we know best, is the idea of channel slavery, meaning a way of controlling a labor force.

[00:45:01] Really trade them, not as persons in any S sense to the term, but simply as property with no rights at all that you have to recognize or respect or treat fairly. That it was the basis of the labor system in the southern plantation. Colonies, meaning Maryland, Virginia, the two Carolinas in Georgia. These are all commodity exporting colonies.

[00:45:24] Maryland tobacco, North Carolina tobacco is a dominant crop in South Carolina. It’s actually rice and indigo and Georgia is tobacco. And again, Georgia’s still somewhat underpopulated and is still very much a developing settlement. Some ERs were involved in the slave trade, not that many. The famous Aaron L.

[00:45:45] Lopez family, actually a Sardi Jewish family living in Rhode Island were active slave traders. But the, it was the Royal, well, originally, the Royal African Company, and then a whole variety of British, British merchants were actively involved and dominated the 18th century. Atlantic slave trade, and not just in North America, but more importantly to the West Indies and Latin America, and it’s important not North America.

[00:46:08] It was actually only a very trivial part of the slave trade economy. The reason for that is that North American slavery was the one slave system in the Western Hemisphere, which became self-sustaining, meaning by the Revolution era. It did not really depend numerically the continued presence of the slave trade.

[00:46:29] North American slaves were reproducing themselves demographically. It wasn’t the case in the West Indies or Brazil with the other great slave settlements because part because the sugar economy is so profitable, masters could, you know, since worth their slaves to death and not worry about the consequences.

[00:46:46] So I, it’s an uncomfortable thing to say, but if one had a choice of where do you wanna be slave, there’d be something said, which of course a terrible proposition. You shouldn’t even use the speculatively, but I’ll use it anyhow. North America would probably be the better destination or whatever. So the British concern, it is part to note that, as I said before, the, the maintenance of slave trade was an important part of the British, and I don’t mean just the Americans, an important part of the British imperial economy.

[00:47:16] And there is a passage in the declaration, which was eventually deleted, which blamed George II for keeping the slave trade alive. In part because they recognized, find us recognizing that they really didn’t need the slave trade that much. They were willing to see it cut off, but the king because the slave, as I said before, in both the British merchants actually for the British monarchy, going back to the late 17th century, the slave trade had been a significant form of capitalism, but that they were practicing.

[00:47:46] But I think what Samuel Johnson said, it was deeply embarrassing. And so I, I, I haven’t offered the second definition. So the second definition of slavery is essentially political. To be a slave means to be governed by laws as to which you have not consented.

[00:48:02] Kelley Brown: Mm.

[00:48:02] Jack Rakove: So that’s a meaning, which, you know, you could say it, it echoes, it resonates with chattel slavery, but it has a specifically political context.

[00:48:12] You know, the famous city rule, Britannia. Britannia rules the waves and Britons never, never, never shall be slaves. When you say Britain’s never, never, never. Shelby slaves, you don’t mean they’re back, that they’re to be picky tobacco or flooding the rice patties in South Carolina, you mean they’re not gonna be governed as the slavish populations of other absolute states.

[00:48:34] They will have representation, they will have political rights. But what happens in 17 74, 17 75, it’s a kind of function of political speech. These two terms start to converge. They start to be conflated. They’re not used inter permeability. But what Samuel Johnson says that in effect, he’s kind of playing off, it’s not a pun, but it does have that association, and I think the Americans found it embarrassing.

[00:48:58] I mean, with good reason. Because, you know, they did have a flourishing slave economy. Now, some questions at the end of the 18th century, whether there’s plantation slavery in North America might have a half life or shelf life. It has to do with part of the upper south, with the soil depletion nature of the tobacco economy.

[00:49:15] You know, tobacco, tobacco takes a real toll on the land and an economy, which would, which would make slavery much more profitable in the 19th century, and helps to explain why we had a civil war in 1861, the economy, and then of course the invention of cotton gin, which makes it much more efficient, productive, that had not yet emerged.

[00:49:35] Americans were not growing cotton in the 18th century. Cotton was a very hard copter road. That’s so point of cotton makes the processing of, you know, the cotton fiber much more efficient, much more profitable. There’s some southern thinking that perhaps we won’t be stuck with this system forever. There is a, there’s a beginning of a moral reckoning.

[00:49:55] The idea that slavery is, it’s, there’s something fundamentally wrong about it. Historic Jewish argued that a moral reckoning of slavery really only begins in the middle of the 18th century. And that’s, again, that’s the kinda shocking notion for us to come to grips with. But you, there are ways to reconcile chattel slavery to existing legal norms.

[00:50:15] John Lock has a famous discussion of this in his second treatise to government and so on. But you beginning major are really driven, I think, by religious forces. The Quakers played important role here. Slavery becomes morally objectionable and people have to start to reckon with its consequences. Though they’re not sure exactly how to do so and so, they’re only starting to wrestle with it, it’s gonna take them many more generations.

[00:50:37] You know, we don’t really have serious abolitionism in the United States until the 1830s. I mean, it’s easy to, opposed to slave trade, it’s hard to imagine. What if you abolish slavery? What happens then? What do we do with the Freeman? It’s a problem that Jefferson wrestles with. Again, it’s offensive to us, but I think Jefferson was wrestling with it sincerely, and he has a famous discussion that’s in query 14 of his notes on the State of Virginia,

[00:51:02] Kelley Brown: Professor Rakove, I’m wondering if we can move to talk a little bit about diplomacy during a revolution. In revolutionaries, you have a chapter that’s entitled The Diplomats in which you Write, quote, the Diplomacy of the Revolution is essentially a tale of three treaties, three cities, and on the American side, three men. Could you briefly tell us about these treaties, cities, and men, and how they powerfully shaped the fate of the aspiring New Republic?

[00:51:29] Jack Rakove: The three treaties were the two treaties that Benjamin Franklin negotiated with the monarchy of Louis says Louis, the 16th. In 1778, there was the two. There were complimentary treaties of lines and commerce, which were done simultaneously, and then there was the provisional Peace Treaty of 1782, which was negotiated between the American diplomats and their British counterparts.

[00:51:56] The three cities of course, were Philadelphia, the American capital, London, the British Capital, and Paris, America’s great ally, and the Sydor, the treaty negotiations. And the three men who mattered were the three reading American diplomats, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams. The interactions among the three diplomats was somewhat complicated for reasons, the reasons I’ll say something about, well, the original idea behind the so-called motto treaty of that John Adams and his committee drafted in 1766 was, Americans should rely on their commercial power.

[00:52:34] The idea that this is a word prosperous and consumer-oriented society already, and that’s gonna be the great incentive to get nations to IDE with this. But in the end, the am The Americans have to make a pretty straight military alliance with France and we depended upon that alliance for a whole variety of things.

[00:52:51] We, you depend on the French, you get to manufacture arms. It’s important to have French troops available to reinforce our forces in a critical moment in attempting 81, having the French Navy. Come in and seal off Morico Wallace in his army after they invaded Virginia, and were ENC camp in Yorktown to seal them off using a combination of French American troops.

[00:53:12] And then the French Navy effectively isolate corn walls and make you surrender inevitable, thereby ending the war. So that’s the three treaties that you have to pay attention to. Three cities to try to figure out, of course, more of the diplomatic objectives of the three major powers. And the three diplomats really were, I think, the real heart of the story, Franklin and Adams and Jay.

[00:53:35] And so let me tell that story. So there had been a lot of controversy in the First American Commission to France going back to late 1776. 1777 included Franklin Sine from Connecticut and John Adams. Dean in particular got involved in a quarrel with another guy named Arthur Lee, who was one of the members of the Virginia Lee family and was also attached to the mission kind, how Congress decided they had to simplify its diplomacy.

[00:54:06] So it, it recall Adams and Dean and Arthur Lee and really let Benjamin Franklin in charge and that was great. Franklin was, along with Thomas Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were the two most sophisticated co involved Americans of their era. Franklin was much admired. Franklin was a genuine scientist, you know, all that stuff with the kind of electricity that was real science, 18th century.

[00:54:30] He wasn’t just some kind of prank by kind of, uh, amateur inventor. So Franklin Franklin is a, is a great celebrity in, in 18th century culture, and Franklin knew how to play with his own image. So Franklin negotiates a treaty, the Treaty of Alliance of Commerce, and, and, and he stays in London. And then what happened?

[00:54:47] It’s kind of complicated story. In 1779 when the British Army is now rampaging through the southern colonies, it’s the third phase of the war. The questions arise whether or not there might be a negotiated piece with actually Catherine the grave from Russia lines up playing a critical role here.

[00:55:05] Whether there might be some kind of negotiated piece of what’s become now a general, you know, imperial war, which France and Spain are involved as well as Britain. And if the British Army is occupying big parts of the South, it might be the case that the Americans Union will lose control of significant parts of their territory.

[00:55:26] So there’s very complicated debate with what kinds of the French say you French as Americans. You have to tell us what your terms of these are. The northern states wanna protect American access to the North Atlantic fisheries. Which were important. The New England economy, the southern states wanted to ensure that Americans have navigation rights along the Mississippi River, which was then subject to Spanish control because the French had given Spain control of the Louisiana Territory at the end of the seven years war.

[00:55:56] So you had this complicated situation. There’s this Congress gets very divided over this, over its terms of peace you for months, and then finally they resolve it. They appoint John Adams to make him commissioner of Kind, commissioner negotiate peace, should peace treaties arise. They appoint Henry Lawrence as another to serve overseas.

[00:56:19] They send John Jay was then the president of Congress. They send John Jay off to Spain to try to work things out with the Spanish. And none of these guys make much progress doing anything. Basically, everything rides on the outcome of the war. So eventually what happens? Well, the, the, the one other condition here is the French government insists that the Americans have to follow when, if they, if any peace negotiations arise, they have to take guidance from the French, meaning not just Louis says the king, but comb to Chen, the French foreign minister, the Count de Chen.

[00:56:56] It was a very, a very skillful dip diplomat. And then what happened, and it’s really quite interesting, is that after the Battle of Yorktown, a word reaches news the outcome pretty quickly. During the, I think during the late, the late winter of 17 one, early 1780. Early. Yeah. The early winter of 1781. 1782.

[00:57:18] George, I third, first things, maybe you should resign the monarchy. Warren North says, no, you really have to. You are the king. You have to remain in office. And then communications begin between the Americans and the British. And first it begins with Franklin, who has a couple contacts on the British site and then the British start sending emissaries.

[00:57:37] And then John Jay, in his two years in Spain has gotten nowhere. The Spanish don’t wanna recognize the United States. Jay’s made very little progress in opening up some kind of amicable relationship to Spain. Frank says, why don’t you come join me in Paris on the Peace Commission, Henry Warren had had said sale, but was captured in sea.

[00:57:57] So he is been in prison in the Tower of London. He’s the recent very end. And John Adam has been off in how mostly trying to negotiate financial assistance from the Dutch. Eventually the Americans make the decision that they’re gonna ignore their instructions from Congress. Congress had said, follow the advice of the French.

[00:58:17] Don’t do anything independently. I think Frank initiated this, but then Franklin, I think he had, think he had an attack of God or whatever his way up. John Jade wound up taking the lead negotiations. John Adams was a bit to slow up in part because John Adams really detested Franklin and he didn’t really wanna beat his company and it took him a lot of courage or whatever to, to kinda get in, get a position where he’d be willing to be in the same city.

[00:58:40] So Adams shows up a bit late, but in the end, the Americans all agreed. Frank in sense was the one a little bit reluctant in part because he played so active rope. In the end, they all agreed, we’re gonna cut our own path, we’re gonna negotiate our own treaty, and we’ll tell the French about it when it’s over.

[00:58:55] The French really knew that something was up. I mean, they’re doing this in Paris. The French man desire the French was to, they break off the American colonies from British control. So it was much of displeasure of Congress when Congress learned that the commissioners, they had violated their instructions.

[00:59:11] But in the end, the British negotiator was actually fairly generous. They gave us boundaries all the way to the Mississippi River. The British retain Canada, and in the end, I think it’s seen as, as, as a fairly successful negotiation on our partner. But it’s a little dicey because you have this whole complicated situation about who’s gonna sit at the same table, which, and, and negotiate with, uh, who else on the other side.

[00:59:34] Kelley Brown: That was really fascinating. I was like scribbling down details about that as you were talking.

[00:59:40] Alisha Searcy: I want to ask you this. This is a quote if well-meaning, but misguided citizens felt it necessary. If this was the price of persuading moderate anti-federalists to accept constitution. You write James Madison would not only support it, but take the lead in its adoption.

[00:59:58] Can you talk about the central role that the Bills of Rights played in 18th century British law, early state constitution, and ultimately Madison’s role in drafting the first 10 amendments of the US Constitution?

[01:00:12] Jack Rakove: Let’s go back to 1776. So part of the movement towards independence was to restore legal government in really 11 of the 13 states.

[01:00:23] You didn’t have to go to Connecticut, Rhode Island because they had no royal officials at all. They were the kind of the so-called corporate colonies. Everywhere else there were officials appointed either by the crown or in the case of Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, by the proprietary families, the pens and the Calverts who had the rights to govern, but who took their instructions even so from the crown.

[01:00:45] So legal government had effectively collapsed in 17 74, 17 75. You had to restore. The only way to restore it was to write constitutions, which in fact was itself a very novel activity. So in a certain sense, the invention of the written constitution, which plays such a fundamental part in American notions and what constitutional is, began almost accidentally or incidentally, not incidental.

[01:01:10] Well, the adoption were in constitutions, that great American innovation was in a sense of byproduct of the revolutionary crisis of 1776. You needed to restore legal government. The only way to do that was to. Describe what the new governments are gonna look like. You could have just restored the OK Colonial regime because you cut the whole monarchical royal part out of it.

[01:01:29] Part of the process of writing constitutions, though, was to add bills of rights, or what they would call actually, declarations of rights was the preferred term to add declarations of rights to the constitutions. Eight of the states did that in only two of the states, Pennsylvania in 77 6, and then Massachusetts eventually in 1780 were the Bills of Rights, actually part of the written Constitution itself.

[01:01:58] The other six states, they were in effect parallel or accompanying documents. Their purpose was not to issue a set of legal commands that would be judicially enforceable. It’s rather to endorse a set of principles that would be consistent with forming Republican government, which would recognize many of the standard procedures of common law jurisprudence within the Anglo-American tradition.

[01:02:21] The documents are intended more as a kind of preface to the introduction or the promulgation, the adoption of a written constitution than being part of a written constitution itself. The operative verb they often use was not shale. If you give a legal command, you would say you give the mandatory shale.

[01:02:39] Think about the second amendment. The right to keep in mirror arms shall not be infringed. In the 1776 declarations. The operative verb is ought and ought, has less force, ought operates as a kind of moral obligation, but not a legal command. That’s our starting position. Then what happens is we wage a revolutionary war.

[01:03:00] The RS of confederation were drafted in 17 76, 17 7. They weren’t fully ratified, 1781. They were found to be incompetent fairly early, but it was very difficult to amend them. So eventually in May, 1787, the general convention, the what we call the constitutional convention, or the Federal Convention meets in Philadelphia.

[01:03:20] Well, it met a couple weeks late ’cause it’s hard to form a quo. The 18th century, it’s supposed to be in mid-May. It meets actually Fortnite later gets down to business and then it spends the next three and a half months or so, June, July, August and half of September writing the Constitution. Then it Adjourns Constitution is published on September 19th, which happens to be my older son’s birthday, my older grandson’s birthday, and Americans start debating it and one of the first complaints to emerge was whether or not the Constitution was deficient because it lacked a bill or a Declaration of Rights.

[01:03:53] The delegates, the framers, had discussed that brief toward the very end of the convention. George Mason, who had been the main author of the Virginia Declaration rates of 17, 17 76 said, yeah, we should add one now. Yeah. I think he basically felt the framers should adopt the language he’d used back in Virginia in 1776.

[01:04:11] But for a variety of reasons, the framers felt you didn’t really need the document. You know, they weren’t in the revolutionary situation in 1776, legal governments existed. They weren’t forming governments and knew they were simply revising the existing form of a federal constitution. They just didn’t take the issue very seriously.

[01:04:28] But Mason did, and other leading anti-federalists. In September, October 78, 7, when the Constitution comes under Republic of Aid, felt this was a truly important question. So that became one of the leading edges. Of anti-Federalists agitation. The, the support of the Constitution are known as the Federalists a word.

[01:04:49] They kind of preempted, the opponents of the Constitution are known as the Anti Federalist. They were the people who were opposed to the Federalists. So kind of, there’s a little kind of gimmicky maneuver going on here with the actual names. The anti-Federalists actually wanted a number of other substantive changes in the Constitution.

[01:05:06] For example, I think probably their leading concern was to deal with the whole system for financing the national government. They wanna go back to the system which it operate under the Article Federation, where the national government to raise funds. From the states would issue what we called requisitions that say the state, we need X amount of financial support from you.

[01:05:29] They’d leave it to the states to determine how and when the appropriate taxes would be laid. Madison and Hamilton, others felt there was a terrible way to finance the national government. National government had had to have its own power of taxation. It could not be dependent on the states. So there are a variety of ubstance changes the anti-Federalists wanted to make in the constitution.

[01:05:45] James Madison, who along with Hamilton plays probably the leading role in organizing the federal strategy for ratification from the fall of 1787 down into the summer of 1788. Madison was in Hamilton, were milled, devoted. The idea that we don’t wanna have a second convention, we wanna get the constitution adopted in a clean and need form, and we don’t wanna open it up for further amendment right away, because if you do that, who knows what the outcome’s gonna be.

[01:06:17] A lot of people, including Madison’s good friend, Edmond Randolph, who actually read the Virginia Plan and start a Constitution convention, wanted to have a second convention, had a second convention. You just have to send delegations. You send delegations. They probably have instructions. They had instructions.

[01:06:31] They probably tell them, here are things you don’t want to agree to through the first constitution. I mean, you just opened up the whole framework for debate. So Madison felt first that you had to do everything possible to adopt the Constitution in a clean and simple form. And so that’s why the ratification conventions, which had the authority within the states to say whether or not the Constitution would be approved or ratified, could only say one of two words.

[01:06:55] They could say, yes, we ratified, or no, we rejected. You could propose amendments, but you could not make the adoption of the Constitution contingent upon the adoption of those amendments first. So that’s the first main objection. The second was Madison and other federals actually have qualms, reservations.

[01:07:15] About the wisdom of adding a bill or a Declaration of rights to the Constitution. So let’s kind of operate the level of high constitutional theory. There would be one advantage to doing so if you thought of a constitution as Americans now did at Supreme fundamental law to insert the wording of a right into a constitution, would in one sense clarify and provide full legality legitimacy to its status, but then you had a problem.

[01:07:48] What happened if you left some rights out? If there were other rights you wanted to protect and they were not included, would they not be relegated to some fair status? That’s why we have the ninth Amendment. Amendment says The inclusion of certain rights in this constitution shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

[01:08:06] It’s a way of saying that while we’re adopting in the first eight amendments, we, while we’re adopting a set of specific rights, there may be other rights out there that deserve full constitutional recognition. We have not yet exhausted the list. Madison’s second concern was even the sense, even more, I won’t say curious, but if you think, what does it mean to have a right?

[01:08:27] What does it mean to have the free exercise of religion? What does it mean to have freedom of speech? It’s very hard to codify the extent of that, right? In a kind of economical or concise formula, the kind that Americans seemed to like. So the process of converting a right into a a specific textual form also raised some questions.

[01:08:48] So Madison had these gen genuine quals about adding a bill of rights to the Constitution. They had a sex quality they had to do with the nature of the problem itself. But on the other hand, Madison was, and along, I think along with Hamilton, was the great strategist of constitutional ratification. And in his view, uh, and this remains too, you did not really need to have a bill of rights.

[01:09:11] The Constitution would be actually fine without it. And in fact, it’s worth knowing that the Federal Bill of Rights was a pretty insignificant document in our history until the 1930s. It doesn’t really have much importance at all in American Constitutionalism until you get to the 1930s, and that is important, really does take off.

[01:09:31] But Madison felt, in Madison belief, there were a lot of, as, as I said in in the passage you quoted, there were a lot of well-meaning, but misguided anti-federalists out there. They didn’t understand all of Madison’s objections or ma all of Madison’s qualms. They wanted to preserve the union. They did have some serious reservations.

[01:09:48] You had to do something to a sl. Their misgivings, even if felt the Bill of Rights was not really necessary, the adoption one would be politically useful. In effect, it would be the last act of constitutional ratification. It would, it would help to unify Americans as a matter of public opinion. Most members of Congress did not agree with Madison on this.

[01:10:08] Madison wrote a vote in August, August 8, 7 89, where he says he describes this whole project as the nauseous project of amendments. He didn’t be nauseous to himself. He meant that he had to convince most of his colleges in Congress in both houses that this project was worthwhile. They had other priorities.

[01:10:23] Most Federalists thought. The Constitution was ratified. We don’t really need to do this. Most anti-federalists recognized that the amendments they really, really wanted were not the ones they’re gonna get. But Madison felt that to bring the whole process of constitutional adoption to a satisfactory conclusion, adding a bill of rights for Declaration of Rights would fulfill that function.

[01:10:44] And I think in the end he was right. It wasn’t because it was constantly urgent, it was because it had an important political function to play.

[01:10:51] Kelley Brown: That is so fascinating and um, it really is. I mean, I’d love the story of the Bill of Rights and the whole process of Madison bringing it through. And I think as we get to the end of our time together, I’m wondering if, before I ask you to read a passage from revolutionaries, if you could sort of briefly answer one question that I think really aligns with what you were just talking about.

[01:11:14] When people talk about the American Revolution, they often rightly focus on that older generation like. Adams is, and Franklin and Jefferson, but that next generation, right, that is brewing at the time, people like Madison or Hamilton. Can you just talk a little bit about that second generation or that upcoming generation and the role they play in kind of making the ideals a reality?

[01:11:41] Jack Rakove: Yeah. I have to say that the concept of generation is itself kind of a nebulous term. Many of us think about the greatest generation, the generation before World War ii, which actually included my dad and all of my uncles, except for one who was an engineer who were all in the armed forces.

[01:11:57] Other people have written about in world is about the generation of 1914 people came outta a long era of European peace and then found themselves stuck in the trenches. And for five years of bloody warfare, which transformed European culture and politics in very radical and often disturbing ways. So when I wrote revolutionaries, I did have this problem in mind.

[01:12:19] They, there was an old essay published by a political scientist named John Roche, I think back in the 1950s when I was still a kid called the Founding Fathers Young Men of the Revolution or something like that. And they’re called attention people like Hamilton and. Madison. Madison was born in 1751 and Hamilton was born in 1755.

[01:12:41] There’s, there’s some occasional dispute about that. Jefferson was born in 1743, so Jefferson is only 33 years old when he wrote the Declaration. So in a sense, I think they came of life with the revolution itself. And yeah, they do have the older leaders, I mean, Franklin was born in 1706. I mean, Samuel Adams, I think was born in 1723.

[01:13:02] There are general generational differences, and when I wrote revolutionaries, you know, one of my things was to say that in effect, the revolution created a set of opportunities and the possibilities and a set of challenges that recruited a surprisingly talented group of people actually have different ages.

[01:13:19] I mean John Anns, as well as Madison and so on. They were a bunch of provincial. Ernest provincials Living to, you know what my mentor, Bernard Bailey called the marshlands, the far periphery, the British Empire. Their eyes turned eastward towards London, the great imperial metropolis, rather than across colonial boundaries.

[01:13:39] You lived in Boston, you didn’t really care that much what was going on in New Haven or whatever. They acquired national identity, but they were challenged to kind of pull off the first successful colonial colonial war of national liberation and to write new constitutional government, an enterprise that no one had really done in, in living memory, and to rethink the fundamental principles of self-government.

[01:14:01] Rid themselves of monarchy and aristocracy and asking what form of government do we want to have now? And so, and of course as I, it is said in re in revolutionaries in my chapter I asked is called the Greatest Law Giver of Modernity, which is actually a bit of a punt on something John Adams written in 70 76 when John Adams wrote in Sing Go and said to her, you and I should have been sending a life at a time, one of the greatest law givers of antiquity would’ve pushed over it.