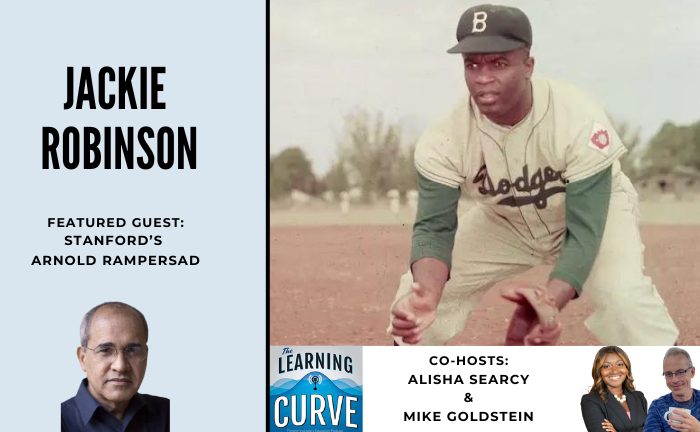

Stanford’s Arnold Rampersad on Jackie Robinson

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve Arnold Rampersad

[00:00:00] Alisha Searcy: Welcome back to the Learning Curve podcast. I’m your host, Alisha Thomas Searcy, Southern Regional President of Democrats for Education Reform. And I am joined today by a new friend because Albert is out. Our Learning Curve baby has arrived, and so he’s going to be out on paternity leave for a couple of weeks. And so, I have a special guest host joining me. Welcome, Mike.

[00:00:24] Mike Goldstein: Alisha, it’s great to be your new friend. Congrats to the new dad and look forward to our session today.

[00:00:32] Alisha Searcy: Absolutely. So, Mike Goldstein, tell the listeners who you are.

[00:00:37] Mike Goldstein: Besides being a dad, also, of two teenagers, I am a former charter school founder who now runs a learning lab focused on math tutoring, a company called QMath that has 3,000 tutors worldwide. For Pioneer Institute, I’ve just started some ethnographic research about homeschool parents, and particularly how they use education savings accounts.

[00:01:04] Alisha Searcy: Ooh. Well, that sounds very interesting. I look forward to hearing more about that.

[00:01:09] Mike Goldstein: Yes. And I’m psyched for us to talk about a couple stories we’ve read this week.

[00:01:15] Alisha Searcy: Yes. And I’m, you know, I’m going to talk about this charter school story in New York, and I’m very curious about your thoughts. It’s by Alex Zimmerman, and it says, with vote to approve 10 charter schools, the sector’s growth in NYC is once again on pause.

[00:01:33] And so this article talks about So, first of all, that it’s still hard for me to believe that we have charter caps and I know it’s kind of a northeast thing. I live in the south. We don’t do charter caps and I’m very happy about that. But in this particular story, it talks about a number of charter schools that did get charter caps.

[00:01:51] All of authorized or let’s say renewed or even have the ability to expand, and there were some that were not. And so, I don’t follow the politics in New York around charter schools much lately, but it feels like something is a little funky about the schools that got approved and those that didn’t. And when I say that, I mean, it seems like the authorizer, and we’re talking about the State University of New York Charter Schools Committee, you One was intentional about approving schools that were already in existence.

[00:02:24] So, we’re talking Success Academy, we’re talking about Zeta Charter Schools, which we all know are very high performing schools that have done great work in New York City or in New York State. But there were a couple of other schools. that did not get a charter and they weren’t even recommended for authorization from the staff.

[00:02:44] And so on one hand, it’s great that schools are being expanded, that there’s a track record here for these particular schools that have obviously done great work and probably deserve to be expanded. and deserve that growth. On the other hand, as someone who has led a network of charter schools, starting with one startup, you wonder about the opportunities for those charters that don’t have the political connections, the resources that some of these larger CMOs would have.

[00:03:14] to work the committee, to organize parents, to do all of the things that perhaps may influence this process as well. So I’m wondering, Mike, if you’ve heard about this story, if you know much about this, but that’s the story that I wanted to bring to light. I’m obviously a supporter of public charter schools, I ran a network of schools, and I feel very strongly that Charter schools are important in the landscape when we talk about public education from an innovation standpoint, from a choice standpoint, and being able to learn about best practices in public education. But when we see decisions like this, I don’t know if it furthers What is the purpose of charters? Is that what we intended, those of us who are charter supporters? What do you think, Mike?

[00:04:00] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, it’s such a great question, and I don’t think, you know, I wonder, our podcast listeners may be privy to this, but among charter school supporters, that there’s this competing points of view where you have limited numbers of new charters that are allowed to open in a place like New York or Massachusetts.

[00:04:21] Should you give those limited schools to, like you said, the big boys, the proven ones that already have 25,000 or more students that have shown they can create one more new school that parents will like and that will do well with kids? Or should you protect that slot for an entrepreneurial school founder who has a very different idea about what the school could be like, and they have no proven track record yet.

[00:04:52] That’s the whole point of giving them a charter. And I don’t know on this one, I do feel like our friends that come at this from both sides have good points. In other words, we want this innovation to happen, and it’s a shame that the idea is we’re giving out this scarce resource. of both meeting the existing parent demand for a great school system like success, or we can give someone else a shot at making what might be an even better school to serve a different cohort of kids or to, you know, have a different curriculum or to have a different staffing model.

[00:05:31] And Massachusetts certainly went down the road of emphasizing the existing model, like schools like Match and Uncommon and KIPP. The opportunity was to grow. We were essentially given the opportunity to open our second or third school before new schools were allowed to open. And I don’t know in hindsight if that worked out the right way, because what’s happened is, I think, the No Excuses Charter model, that was thriving in Boston for many years, kind of fell on hard times more recently. And it may have been a stronger charter movement if we had more variants, I suppose, in the mix of what parents could choose from. So tough question.

[00:06:22] Alisha Searcy: It is.

[00:06:22] Mike Goldstein: Charter on charter crime, if you will.

[00:06:25] Alisha Searcy: Yeah. So, to be continued, right, we’ll see what happens with this, but I hope that the folks that didn’t get it. Renewed, we’ll go back and try it again because we, I think, need all of them in the sector.

[00:06:37] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, I agree. I mean, when I first applied, we got rejected. So, you know, you got to dust yourself off, learn from the feedback and try again.

[00:06:46] Alisha Searcy: Yes, it’s the name of the game. And let me clarify, we need all of these high-quality schools in the sector.

[00:06:52] Mike Goldstein: Yeah, such a key point. And I think what you and I would agree on, but what’s so tricky, you don’t know when somebody approves a charter if they’re going to be good. Like, at the time they apply, you kind of have this 50-page business plan and a handful of people that say, hey, we’re going to do a really good job of this. But, you don’t know what that school will really be like in three to five years.

[00:07:16] Alisha Searcy: You’re so right, especially when you think about the political climate, the policies that are in place. You know, we start talking about facilities, and don’t get me started, our listeners have heard me say this before, but one of the schools that I led in the network, we had a 127,000 monthly bond payment for the facility that two of the schools were in.

[00:07:37] So, you imagine, right, someone who has led a school, what you could do with 127,000 a month if you didn’t have to pay for a building. So I completely understand your point, right, that you’ve got this plan. But you don’t know, given all of the circumstances, who you hire and all of that, and how that will shake out.

[00:07:59] Mike Goldstein: Amen.

[00:08:00] Alisha Searcy: Good point. Well, what’s your story, Mike?

[00:08:03] Mike Goldstein: Okay, so I picked this story from Chalkbeat, where the headline reads, this is from July 17th, New York City planning a school cell phone ban for February. According to principles. So, few contexts here. So, this is a district wide plan to ban school cell phones, and it will roll out in the month of February, and this is not an official statement yet.

[00:08:34] from the school district of New York City. This is a couple reporters talking to a bunch of principals, and the principals are telling them off the record, this is what’s planned to happen. So, Alisha, I have three quick reactions to this cell phone ban for kids in school story. First one, as a school leader, which I bet you will not along with, is February is a terrible time.

[00:08:58] to roll out any new policy. Ideally, maybe this September if you’re ready, maybe next September if you’re not, but like the mid-year ones, they kill a school. Oh my god, it’s like all of your energy suddenly goes to try to enforce the policy. So that’s my first reaction. Don’t do that. Don’t do February. My second reaction is, I do generally think the school cell phone bans.

[00:09:24] Our good policy. The devil is certainly in the details, but I’ve seen a bunch of schools successfully roll out these things. My own two kids go to a public school that has a cell phone ban policy, and it works reasonably well. They leave their phones in, you know, a pouch, and it’s kind of locked up. And there’s a little bit of kids messing around and kind of stealing each other’s phones, at least for my older one, but, you know, it goes reasonably smoothly, and teachers report that they’re relieved to have the cell phones not in the hands of kids during class.

[00:09:59] So I do think that the policy runs in the right direction. With that said, a lot of these top-down policies get implemented so badly. I would imagine that some of the New York City schools will roll this out horribly and there will be very angry kids, teachers, and parents because they won’t get the details right.

[00:10:19] Alisha Searcy: Yeah, I would agree with you. So, I’m gonna, you know, surprise some people, but I actually don’t like these cell phone ban policies. I understand, as an educator, that you want students to have as few distractions as possible. I also believe, though, that we’re still running an education system that looks like it did when you and I went to school.

[00:10:45] And I think at some point, we have to figure out how do we include technology, including cell phones. I’m not just talking about computers and laptops and laptops. iPads and things, but how do we incorporate cell phones as a way to deliver instruction? And so that’s a different discussion, but I think your point is exactly right.

[00:11:05] When you talk about doing something in the middle of the school year, essentially, you’ve already gotten your norms in place, right? And your routines, and now you’re going to disrupt that. And so, there’s all of that. And I also think parents are, you’re, you’re exactly right. Going to be very unhappy. I’m a mom, you’re a dad, you get this.

[00:11:23] I think that. You know, I like that if something happens, I can get to my daughter very quickly. And so, there’s a bigger conversation here about the role of cell phones and how we use it in instruction and safety. You know, we live in a time of school shootings and school violence and those kinds of things.

[00:11:40] And you want to be able to get to your kid. There’s a conversation about when you have these top-down policies in the middle of the school year. And all of the things. And so, I think we’re going to keep having this conversation. It’s going to be interesting to watch how California does it, how New York does it. There are probably some conversations happening in the South where I live. It will remain to be seen how this is done successfully.

[00:12:03] Mike Goldstein: Yeah. And my final thought, just to build on yours, is it’s why I’m skeptical that the big school district system that we’ve had so long adds a lot of value. Because I bet if parents were listening, they would say, wow, I’m on a world where Alisha can run her school her way, because she has a totally reasonable point of view, and Mike could run his school his way, with his things, and as a parent, I get to choose. Instead of, sort of, I have no choice, because all of the schools that are available to my child have one policy, you know, and so it’s sort of an argument, even though it happens to be about cell phone bans.

[00:12:47] I think it’s an argument for school choice, parent choice, and I don’t know if this is the right word, but I would sort of say school leader choice. Like you and I would both want to do what’s authentic to us. And I would be, of course, delighted to like to recommend your school to parents. It’s not that I feel strongly this policy should or shouldn’t be pervasive, instead I feel like I imagine in one context I like it.

[00:13:16] And in another context, I like yours, where you’re using the cell phones, but you have other ways. What I know is that in your school, if you have cell phones being used. What you would not tolerate is that the kids are like not paying any attention to the teacher and screwing around on their phones the whole day, which is probably the reality as described by school principals in New York City. So, it’s like, ugh, you get to this question of authentic implementation for any ideas.

[00:13:42] Alisha Searcy: You’re exactly right. I love that point. Great story. for sharing that, Mike.

[00:13:46] Mike Goldstein: You bet.

[00:13:47] Alisha Searcy: Coming up after the break, we’re going to have our guest on, who is Stanford’s Arnold Rampersad on Jackie Robinson. So stay tuned.

[00:13:57] Arnold Rampersad is the Sarah Hart Kimball Professor Emeritus in the humanities at Stanford University. He also taught at the University of Virginia, Rutgers, Columbia, and Princeton. Professor Rampersad’s books include The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois, The Life of Langston Hughes, Days of Grace, a memoir coauthored with Arthur Ashe, Jackie Robinson, a biography, which we’ll talk about today, Ralph Ellison, a biography.

[00:14:25] His edited volumes include the Oxford Anthology of African American Poetry. Complete Poems of Langston Hughes, and as coeditor of Selected Letters of Langston Hughes. Winner in 1986 of the National Book Critics Circle Award in Biography and Autobiography, he was later a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Biography and, in 2007, The National Book Award in nonfiction prose for his biography of Ellison.

[00:14:53] In 2011, he received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama at the White House and Harvard awarded him its Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Medal in 2014. He holds honorary doctorates from Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and the University of West Indies, among the other schools. He’s a graduate of Bowling Green State University and earned his Ph.D. in English and American Literature at Harvard University. Professor, it is an honor to be with you today. Thanks for joining us.

[00:15:25] Arnold Rampersad: Thank you very much for inviting me.

[00:15:27] Alisha Searcy: Of course. You are the award-winning biographer of several noted African American figures, including Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison. And Jackie Robinson’s widow, Rachel, has asked you to author the first full scale published biography of her husband, which I’m sure was an incredible honor. And so can you talk about what that was like to be invited by Mrs. Robinson to write the book, as well as offer an overview of why Jackie Robinson’s story. remain so vital to understanding American history?

[00:16:01] Arnold Rampersad: Well, it was indeed quite an honor to be invited to write the biography. This was in the context of the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s entry into the Major League in 1947.

[00:16:13] So it was an honor. But even more than that, for a biographer, there was the access that she gave me to the Virtually all material, written and otherwise, and the sanction, as it were, from her to me, that proved to be very valuable in getting people to talk about Jackie Robinson. You’re right, I mean, Jackie Robinson remains a powerful figure in American culture.

[00:16:40] I think, in part, it’s because he’s connected to, you the question of racial liberation, of social justice, and unfortunately some of the questions that he tried to address in his career as a baseball player, as a public figure, are still with us today in one form or another.

[00:17:01] Alisha Searcy: So, he was born in rural Georgia, which is where I live, the son of a sharecropper and raised in a largely white neighborhood in Southern California. There he became a student athlete, He played football, basketball, baseball, and track in high school and at UCLA. And as he struggled against racism and poverty, can you talk about his family background, his faith, education, perhaps the model of his brother Mack? who himself was an accomplished athlete and silver medalist behind Jesse Owens in the 200 meters at Hitler’s 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

[00:17:38] Arnold Rampersad: Right. Well, Jackie Robinson’s brother, Mac, was very important to him as a kind of model for what he might achieve on the sporting field or in the gymnasium, if you want to put it that way. His mother was a much more powerful influence, I would think. His mother Who he loved and believed in, and who believed in him.

[00:17:59] She was a devoutly religious person, and she passed on that sense of reverence for the Almighty that characterized Robinson for the rest of his life, really, because he never went away, he never became atheistic or anything like that, even when he became extremely famous. So, she was Powerful influence on him.

[00:18:21] Of course, there also were people like teachers and coaches and, uh, at least one religious figure. I needn’t go into that now here, but somebody who was able to guide him through that perilous time of being a young man, especially a young man accustomed to the chairs, uh, from the, from the, you know, the bleachers and so on, in danger of having his head and turned by too much adulation at too young an age.

[00:18:47] So he was helped by a number of people. But the important thing in some ways, the most important thing in some ways, is that he was ready to receive instruction. He was ready to recognize people who were in authority, who could really help him, who had his best interests at heart, be they athletic or social or political. And it was that openness to instruction, I think, that made him the kind of person he became.

[00:19:13] Alisha Searcy: So, I want to talk about something that we came to learn that in, after college in 1942, Jackie Robinson was drafted for service during World War II, and he was court martialed for refusing to sit at the back of a segregated U.S. Army bus in 1944, and of course, we later learned that He was eventually honorably discharged, which we’re happy to hear. And so, in 1945, he then signed with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Baseball League. So, can you talk about this early phase of his career, especially how this army experience shaped him and why he opted to become a Negro National League baseball player and who, if you could also mention are some of his African American role models in sports?

[00:20:02] Arnold Rampersad: Well, one of the most interesting things about Jackie Robinson, given his fame and the longevity of his fame, is that baseball was not his number one sport by any stretch of the imagination. He was a better football player in terms of renown and effectiveness on the field, and also a basketball player.

[00:20:20] So I think that baseball would have come in Third, nevertheless, there was the Negro Leagues, and he did imagine at one point that he would find a home there, and did play for at least one year there in the Negro Leagues, and enjoyed a good experience, and was therefore ready, as a baseball player at least, when Brian Schricke from the Brooklyn Dodgers reached out to him and invited him to take this historic step for the Dodgers, for American baseball, and for the United States.

[00:20:53] Alisha Searcy: Thank you. And of course, we have to point out that one of the reasons why we needed the Negro Baseball League is because African American players were not allowed to play in the Major League Baseball during that time. And so, in the spring of 1945, powerful desegregationists and Boston City Councilor Isidore Mucnic pressed the Red Sox to give Jackie Robinson and other Black players a tryout at Fenway Park. And infamously, with the stands limited to just Red Sox management, Robinson was subjected to racial slurs and humiliation during this sham tryout. So, can you talk about this episode in Boston? And which was the last team to desegregate in 1959 in Jackie’s first interactions with Major League Baseball?

[00:21:41] Arnold Rampersad: Well, it was an amazing experience. He was trying out for the Boston Red Sox and thinking that he and his fellow trialists had done very well, they thought. But of course, it all was Firmly closed and there was no opening there. As for enduring, you know, racial slurs and so on, you know, that was part of the trial, part of the ordeal, and that followed Jackie for a certain, until his second or third year in the major leagues, if it ever went away completely.

[00:22:15] Alisha Searcy: And so, my final question before I turn it over to Mike, Jackie and Rachel Robinson were married in early 1946, a year prior to his breaking the Major League Baseball’s color barrier. And they met at UCLA in 1941, and she of course graduated with a bachelor’s degree in nursing, and they had three children together. Since you’ve known Mrs. Robinson for decades, can you share with us what she’s like as a person, wife, mother, a professional?

[00:22:45] Arnold Rampersad: Well, I would say that she is indomitable, although that word is not used very often these days. She is a soldier, but a very glamorous one in many ways, and that’s what she brought to her first meeting with Jackie. He found it. And her, a very intelligent human being, a very good student at UCLA, a person who had been brought up in a certain fashion, to respect the arts and learning and so on, culture, so, and he was ready for that kind of association. I don’t want a different kind of person, a so called lesser person. So she has remained a powerful figure. She turned 102 earlier this week, or this month, and she’s still going strong. And their marriage lasted, of course, until Jackie died.

[00:23:35] Alisha Searcy: Incredible. Mike?

[00:23:38] Mike Goldstein: Professor, it’s such a delight to talk. One thing that struck me, I’ve sat in Fenway Park many times watching Red Sox games, so it’s jarring to think about the shameful sham tryout that Jackie Robinson endured and, you know, just the idea that you could succeed on the field that he had actually a good tryout that day and then to be humiliated by the response of the managerial group. My first question is just. How did he change over the course of his playing career as he tried to endure the racism that he faced in so many different ways? Was he basically the same person at the end of his playing career and at the beginning, or did he evolve in his ability to kind of navigate all of this hatred?

[00:24:35] Arnold Rampersad: Well, I think, according to all contemporary accounts, he did change. After all, Branch Ricci had entered with him into a kind of three-year agreement that he would, that Jackie would turn the other cheek, that Jackie would not explode. Mr. Ricci knew that he had the capacity to explode, that he’d had not a violent temper, but he said he had a temper when he was facing death.

[00:25:00] A grave injustice. But there was a disagreement between the two of them that the Times called for forbearance on his, on Jackie’s part, and Jackie lived up to that for the first three years. But when he entered the fourth year, by that time, he was much more assertive. And some people didn’t like that, but it was the way he was.

[00:25:22] And there’s people who found him almost abrasive in a certain way. But I think the record shows that he was always, or whatever he was, in keeping with the situation that faced him and faced other Black people at the time. Black baseball players, but also Black people in general. But he did, by the end of his life, they’ve all become really a model for the emerging civil rights movement.

[00:25:47] I think that is something that needs to be stressed, the extent to which, when the civil rights movement started and began to build in its momentum, Jackie Robinson was probably the prime example in the United States of how a black person, a black man in this case, could perform very, very well, stand up for himself to the racist opposition and prevailed because he certainly prevailed on opening the eve saw to be having no chance really to be A star to be inducted into the Hall of Fame one day, which of course he was, but he just simply performed and he performed with great dignity and great skill in the field and he won the confidence of his teammates after initial friction, let’s put it that way, and he embodied, you know, the idea of black excellence in the face of racism. And I think Martin Luther King Jr. certainly saw him that way and spoke of him in that way. Before there was any civil rights action, confrontations, and so on, there was Jackie Robinson, and he was an example to all who had come in the civil rights movement.

[00:26:58] Mike Goldstein: Yes, it’s so powerful, and I want to connect that to a question I was wondering about with my dad.

[00:27:05] My dad was a kid in Brooklyn. In the 40s. I happen to be sitting right here in Clinton Hill section of Brooklyn, and my dad’s favorite player was Jackie Robinson. And one thing I wondered is, was my dad, as like a Jewish guy living in Brooklyn, was he Were lots of kids of all races quickly drawn to Jackie, who was obviously Rookie of the Year in 1947 and, you know, an excellent ballplayer from the jump? Or what was, I suppose, the child level reaction? Kids are often much more innocent about issues of race, um, and I wonder what his experience was like. Because it can be hard, I suppose, to navigate the difference between kids and then the reaction of the adults, which essentially are the parents of the kids.

[00:28:01] Arnold Rampersad: Well, I think Jackie was very fortunate to land in Brooklyn, which has a kind of diverse population, including a large number of Jewish people to cushion him, to welcome him enthusiastically into baseball. He was lucky in that way, just as he was lucky, I think, too, that the Dodgers had a club in Montreal where he could go and live and be respectfully received.

[00:28:29] If not all together, enthusiastically, although I think there’s no reason not to use the word enthusiastically about his Montreal experience, but the Brooklyn experience and the support of people like the Jewish community, as in the Jewish community, who understood in him another version of their historic difficulties facing power, and that community became an important part of his, uh, his life who almost said fan base, but that is true to some extent, of his social support, let’s put it that way, and ideological support, even spiritual support. And he knew that, he respected that very, very much.

[00:29:09] Mike Goldstein: And could you take us back to that first day in April of 1947? I read A stat that I didn’t have the context for, but it had surprised me, which was there were 26,000 plus fans who attended his Major League debut, and more than 14,000 of them, if I read correctly, were African American. That surprised me, because I guess I would have thought the season ticket holders, whoever are the normal fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers, would be there that day. But it seems like that was perhaps already a special day. What can you tell us about that first game, how he was received, who was there, and how it set the stage for that important rookie year with the Dodgers?

[00:29:58] Arnold Rampersad: Well, that’s a pretty large question. I’ll try to answer it. I don’t know what the ticket selling policy was for the Dodgers. I do know that Blacks saw it as an incredibly important moment.

[00:30:10] I mean, everybody saw it as an important moment, but Blacks in particular, you know, desperately wanted the first Black in Major League Baseball to succeed. And no one thought of Jackie Robinson then as a kind of superstar baseball player, so there was a good chance that he might. Not succeed. And in fact, if you look at the baseball press at the time, there were people who seemed to be in a position to know that gave him a thousand to one chance of succeeding in the major leagues. That’s what he faced. And he was able to take advantage of the situation and play to the best of his ability, which was of course, as we finally saw, more than enough for him to settle comfortably into the major league.

[00:30:54] Mike Goldstein: Yes, and he builds this tremendous legacy of success. He’s in the World Series a number of times, and finally wins it. Right. And I thought maybe my final question could be, there’s a quote where Jackie Robinson says, I know that I am a black man in a white world in 1972. In 1947, and at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made. What did that mean, and I wonder if you could connect that to, you know, his ultimate legacy as a history changing figure in our country.

[00:31:35] Arnold Rampersad: I never had it made. That became the title of one of his ghost-written autobiographies or co-written autobiographies. I never had it made so that, you see, that it was an important idea in his life, that he had to make a life. He had to make himself an accepted American figure, and he did so. He did so. He was always aware of his humble birth and upbringing and so on, the poverty that he endured as a child, The redemptive way in which his mother faced poverty and her need to work as a maid and so on.

[00:32:10] And then, of course, when he entered baseball, Major League Baseball, he was always reminded that he never had a maid because of the things he had to go through from people in the stands or just in the general atmosphere. around him, focused on him as a player. So that sense of never having had it made was important in driving him forward, I think, because he wanted to make sure that he succeeded and he wanted to make sure that other people succeeded, people who did not have it made. And I think in the end, he certainly was able to achieve a great deal. for himself, for Black Americans, and for America as a whole.

[00:32:51] Mike Goldstein: Professor, thank you so much. Guests, the book is called Jackie Robinson, a Biography by Arnold Rampersad, and we really appreciate you coming on and joining us so much.

[00:33:22] Alisha Searcy: Wow Mike, that was a great interview. As always, I’ve learned so much and it was fantastic. It’s fascinating to learn so much about the history of Jackie Robinson and the incredible things that he’s done to contribute to America.

[00:33:33] Mike Goldstein: Yeah. You know, I grew up, my dad who grew up near the ballpark, huge Jackie Robinson fan. And it was amazing just to learn more about what that man experienced and how he helped, I think, move the whole country forward. So, what a great thing.

[00:33:49] Alisha Searcy: Agree. That was a privilege. Well, I want to get to our tweet of the week. And just want to bring folks attention to a story that was in the Atlanta Journal Constitution, uh, Georgia School Superintendent Nix’s AP African American Studies course. And so, how ironic, right, that we’re talking about history makers in America, particularly African American history makers, and here’s an educator who leads an entire Department of Education who does not want students to have access to an African American AP course. So, hope folks will check out this story. It’s frustrating and we know kind of what’s happening across the country. We won’t get into the politics of that, but I’ll just say in this country, it would be my hope that we want kids to learn not just about who they are, but the contributions of all people in this country. And so shame on that state superintendent in Georgia. And I hope that no one else follows suit in that regard. Anyway, Mike, it was great to have you with me this week, and certainly looking forward to being with you again next week.

[00:34:55] Mike Goldstein: Hey, I am psyched about our conversation next week with my friend, Professor Joshua Angrist.

[00:35:02] Alisha Searcy: Perfect. We’ll see you next week.

This week on The Learning Curve, co-hosts DFER’s Alisha Searcy and Mike Goldstein interview Stanford University Prof. Arnold Rampersad, author of Jackie Robinson: A Biography. He discusses the life and legacy of Robinson, the hall of fame baseball player and history-changing civil rights leader. Prof. Rampersad talks about Jackie Robinson’s journey from rural Georgia, his athletic triumphs at UCLA, and his struggles against poverty and racism. He continues by exploring Robinson’s military service, his time in the Negro Leagues, and Branch Rickey’s pivotal role in helping Jackie break Major League Baseball’s color barrier. Prof. Rampersad highlights Robinson’s historic MLB career, his profound impact on civil rights, and his enduring legacy.

Stories of the Week: Alisha discussed an article from Chalkbeat on NYC’s charter school growth; Mike reviewed an article from Chalkbeat analyzing NYC’s cellphone ban plan to commence in February 2025.

Guest:

Arnold Rampersad is the Sara Hart Kimball Professor Emeritus in the Humanities at Stanford University. He also taught at the University of Virginia, Rutgers, Columbia, and Princeton. Prof. Rampersad’s books include The Art and Imagination of W.E.B. Du Bois; The Life of Langston Hughes (2 vols.); Days of Grace: A Memoir, co-authored with Arthur Ashe; Jackie Robinson: A Biography; and Ralph Ellison: A Biography. His edited volumes include The Oxford Anthology of African-American Poetry; Complete Poems of Langston Hughes; and, as co-editor, Selected Letters of Langston Hughes. Winner in 1986 of the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography and autobiography, he was later a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in biography and, in 2007, the National Book Award in non-fiction prose for his biography of Ellison. In 2011, he received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama at the White House, and Harvard awarded him its Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Medal in 2014. He holds honorary doctorates from Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and the University of the West Indies, among other schools. He’s a graduate of Bowling Green State University and earned his Ph.D. in English and American Literature at Harvard.

Arnold Rampersad is the Sara Hart Kimball Professor Emeritus in the Humanities at Stanford University. He also taught at the University of Virginia, Rutgers, Columbia, and Princeton. Prof. Rampersad’s books include The Art and Imagination of W.E.B. Du Bois; The Life of Langston Hughes (2 vols.); Days of Grace: A Memoir, co-authored with Arthur Ashe; Jackie Robinson: A Biography; and Ralph Ellison: A Biography. His edited volumes include The Oxford Anthology of African-American Poetry; Complete Poems of Langston Hughes; and, as co-editor, Selected Letters of Langston Hughes. Winner in 1986 of the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography and autobiography, he was later a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in biography and, in 2007, the National Book Award in non-fiction prose for his biography of Ellison. In 2011, he received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama at the White House, and Harvard awarded him its Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Medal in 2014. He holds honorary doctorates from Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and the University of the West Indies, among other schools. He’s a graduate of Bowling Green State University and earned his Ph.D. in English and American Literature at Harvard.

Article of the Week: https://www.ajc.com/education/get-schooled/georgia-school-superintendent-nixes-ap-african-american-studies-course/PXLIFXTXOJFG3CZO6AUDMKLOP4/