Paul Vallas on Chicago, School Reform, and Teachers’ Unions

/in Featured, Learning Curve, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

The Learning Curve transcript, September 6, 2023

Charlie Chieppo: Welcome to this week’s edition of The Learning Curve. My name is Charlie Chieppo. I’m a senior fellow at Pioneer Institute. And I am a guest co-host this week. And I’m very excited for two reasons. One is because our guest is Paul Vallas, who most recently ran for mayor of Chicago. I think he has interesting things to say. But also, because my guest co-host this week is Mary Tamer, who runs Democrats for Education Reform here in Massachusetts. So, Mary, welcome.

[00:00:57] Mary Tamer: Thank you so much, Charlie. I’m happy to be here.

[00:01:01] Charlie: Good. We’re happy to have you here. You’ve come to DEFA relatively recently, isn’t that true?

[00:01:06] Mary: Yeah, it’s been about 18 months, which is hard to believe. It’s been that long, but in prior roles, I’ve been you know, involved with the organization now for a number of years.

[00:01:17] Charlie: Right. Okay. Well, what happens when you get to be my age. 18 months seems like the blink of an eye.

[00:01:25] Mary: It’s been a busy time, so it’s gone by very quickly.

[00:01:28] Charlie: That’s right. All right. Well, why don’t we get right into our stories for this week? My story this week comes something I noticed in Ed Next that caught my attention. You know, amid all the hand-wringing that’s been going on about stalled learning recovery and deteriorating performance of public education, this story kind of reminded me, at least it reaffirmed what my view is, of course, we’re all looking for things that reaffirm our own view, but it reminds me that, I think in many ways we know what works, we just need the political will to implement it.

[00:01:59] Charlie: The story came out of Indiana, and the trends there are similar to the national trends. Students there take the SAT as their required state assessment, and college readiness rates fell again this year, as in so many places. And most Indianapolis-area school districts also saw declines. The thing that amazed me was that in all of the Indianapolis public schools, the state’s — obviously the state’s biggest district — only seven black students in high schools that were managed directly by the district demonstrated college readiness.

[00:02:31] Charlie: Now, when you compare that performance to Indianapolis charters, the contrast is amazing. In the Indianapolis charters, college rates are up. They’re more likely to demonstrate college readiness by orders of magnitude. The city charter schools surpass state college readiness rates among virtually every subgroup. For black students, the top 10 public high schools within the IPS boundaries are charters, and it’s the top seven for Latinos. Now, what makes this so interesting to me is that, you know, there are two different types of charter schools in Indianapolis. There are independent charter schools, then there are innovation charters, which operate in partnership with IPS.

[00:03:13] Charlie: Now both outperform IPS, but interestingly the innovation schools, the ones that operate in partnership with IPS, are the most impressive in terms of their performance. Now I think the key to that is that both of these types of schools have operational autonomy, and I think that for those of us, for example, like Mary and I, who are in Massachusetts, you know, we know that, that is really the key that makes the regional vocational technical high schools here in Massachusetts so successful.

[00:03:44] Charlie: This autonomy allows the schools to make building-level decisions tailored to student needs. And to me, the takeaway here is that the best model is not always the most radical one, or the one that’s most different from the traditional models that we’re used to.

[00:03:58] Charlie: But what’s really important is that school autonomy is crucial, and that ability to be able to make building decisions, building-level decisions about what’s right for your students. So that was what kind of grabbed my attention this week.

[00:04:13] Mary: I found that story so interesting, Charlie, because even here in Massachusetts, you know, we have some in-district charter schools. And so Boston is one of the places where we have independent charter schools that are entities of the state and run by the state — or run independently, but under state control, I should say. But then you have in district charter schools that do have that kind of interesting partnership because they are part of the district. And then they’re also part of, you know, state control as well. But I think when it comes to the success we’ve seen here, it not It hasn’t really been with those in-district charter schools. It has been with the charter schools that are run independently. So, I would love to know what’s going on in the secret sauce in Indianapolis that has led to this. But I think when it comes to autonomous schools, we have seen success with that here. You know, and again, using Boston as the lens, some of the autonomous high schools like, you know, Fenway High, they’re pilot high schools, in fact, and have their own independent boards. And they’ve, you know, they’ve done all right.

[00:05:21] Charlie: Yeah, I think, don’t know this for certain, but my sense from looking at this is that there is a greater level of autonomy in these Indianapolis innovation charters as compared to pilot schools in Boston. And, you know, you mentioned the secret sauce. I wonder if it is the ability to have that increased level of innovation, but still be able to partner with the district. In other words, have the district be open to that kind of thing. So, I don’t know, but it’s certainly worth looking into, I think.

[00:05:51] Mary: It is. It is for sure. One of the stories that has been, I think a big focus for our organization right now has to do with the Mass Teachers Association filing language for potential ballot question that would remove our annual state assessment from graduation requirements. And so here in Massachusetts, students are asked to take MCAS, which is our annual state assessment. And it has been a graduation requirement since the 1993 Education Reform Act of Massachusetts came into being, which did a number of things for schools here in the state of Massachusetts. But chief among them was a new system of accountability and standards for our students.

[00:06:38] Mary: And so, when it comes to this annual test, we you know, for the last 30 years have expected that all 10th graders, which typically is the final year that a Massachusetts student will take this annual test is in the 10th grade. And so, we’re asking all students to meet a 10th grade standard in order to qualify for a high school diploma in Massachusetts. And for the small percentage of students who might not pass this test in the 10th grade, they have subsequent opportunities to take it again in the 11th grade and the 12th grade. And the expectation is for students who might struggle in that 10th grade year to pass that they’re receiving additional supports from their individual schools in order for them to meet this target, in order for them to pass.

[00:07:27] Mary: But I think there’s lots of nuance here that a lot of families are not aware of when it comes to what this actually means. So, we are essentially asking all students to meet a 10th grade standard prior to graduation, and whether that standard is met in the 10th grade or the 11th or 12th grade, it’s still a 10th grade standard.

[00:07:49] Mary: What’s also interesting that I think a lot of folks aren’t aware of is that we’re only asking students to meet — there’s four different standards when it comes to MCAS. And so one is, you’re not meeting expectations. One is partially meeting expectations, you’re meeting expectations, or you’re exceeding expectations. And so, in order to graduate, we’re only asking students to meet that second bar, which is partially meeting expectations. And so as one teacher explained to me, we’re essentially asking every 10th grader in the state of Massachusetts to pretty much get a C minus in order to qualify for a diploma.

[00:08:31] Mary: And so, what the teachers’ union is setting out to do by putting this ballot question in motion is to take away that requirement. And if this were to happen, if they’re successful in getting this question on the ballot and there’s, you know, a process of getting there. But if this were to take place, Massachusetts would be left as one of only three states without any statewide graduation requirement, because, as it stands now, we have something called Mass core standards, which have been in place for a number of years. And it’s essentially saying students are recommended to take, you know, four years of English, four years of math, so many years of science, et cetera. These are recommended standards from the state. We are a state that defers to local control when it comes to decision-making in our schools and in our districts.

[00:09:23] Mary: And so, it’s up to each individual district to say what is the benchmark that a student has to reach in order to graduate. So, if MCAS is to go away and without having set and recommended or required Mass core standards, literally, the only things students will need in Massachusetts to graduate is having met a phys ed and a civics requirement in high school.

[00:09:48] Charlie: Well, you know, it’s interesting, it seems to me that it, what’ll be interesting to follow, and, you know, I think that you and I will be doing more than following it, we will certainly be involved in, is gonna be if this goes to the ballot, it’s always that challenge of trying to get across things that are a little bit nuanced in the process of a ballot initiative, and that seems to me to always be the big challenge here.

[00:10:11] Mary: I think that’s right, Charlie, because my feeling is, and I say this as, you know, the mom of two Massachusetts high school graduates, I think that we for so long have been number one in the country when it comes to our educational outcomes. And knowing that we’re number one and we’re still leaving too many students behind and particularly students of color, low-income students, and our English learners and students with disabilities. But to take away the value of a high school diploma in the state of Massachusetts, I have to believe that there’s going to be some significant pushback to that.

[00:10:47] Charlie: Yeah, no, I think that’s right. And especially given the fact that we’re living in an economy and it’s only going to get more so, you know, where, a high school diploma, that’s not much more than a piece of paper. It’s not going to get you very far. That is just the nature of the way our society is changing. So it’s going to be a very, very interesting one to watch, I think.

[00:11:05] Mary: I think so too, Charlie.

[00:11:09] Charlie: All right, coming up next after the break, we’re going to talk with Paul Vallas. So stick with us.

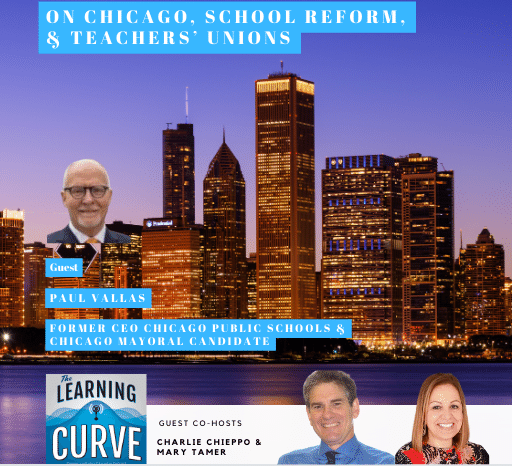

[00:11:44] Charlie: Paul Vallas is a policy advisor to the Illinois Policy Institute and a nationally recognized education and public sector finance expert. He began his career as a policy advisor in the Illinois General before moving on to serve as Director and Budget Director for Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley. In 1995, Paul became the first CEO of Chicago Public Schools, and he has 18 years of experience leading large city school districts in Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Bridgeport. Connecticut. Most recently, he served as a project director for the U. S. Department of Justice, revamping educational and occupational training for over 100 federal prisons. Paul was the Democratic Party of Illinois nominee for lieutenant governor in 2014. He also ran for governor of Illinois in 2002, mayor of the city of Chicago in 2019, and he received 47.8% of the vote in the runoff for Chicago mayor in 2023. Among his accolades include being named, well, one of America’s best leaders by U.S. World and News Report and Harvard University Center for Public Leadership in 2006. Paul grew up in Chicago and still calls the city home.

[00:12:50] Charlie: As you know, certainly Chicago is a great American city. With a tremendous history and unique civic spirit and political culture. You grew up there, served as budget director for the city, CEO of Chicago Public Schools, and most recently ran for mayor. Would you share with our listeners some of your personal background and the formative professional lessons you drew from public leadership in Chicago?

[00:13:13] Paul Vallas: Sure. Well, first of all, thank you for the opportunity to participate in your podcast. I’m the grandson of Greek American immigrants outside of Chicago. I come from a family of six veterans, four police officers, now three, one became a firefighter. Three teachers and of course a Greek family restaurant-owned business, We’re like three generations, three generations Southsiders.

[00:13:39] Paul: And my entire career has been spent on public service. I did spend 13 years in the National Guard. But really when I returned from my military basic training, I went to work for the state legislature I really got my start working in the legislature as, as a substantive staff person focusing on public policies, education, economic development, et cetera. But then I migrated to the financial side. Somebody got this idea that I knew something about finance and the rest is history.

[00:14:13] Charlie: It’s always very dangerous when somebody gets that idea.

[00:14:15] Paul: That’s right. I found myself taking on more and more assignments that pertain to public finance. Let me point out I think the point that I’m trying to make is when you get to work for the legislature, your resume counts for about six months, and then it’s who can solve my problem, who can get me the information that I want. But my governmental service really began as this like committed, dedicated public policy wonk who learned public finance by, in effect, being given a number of financial-related assignments. So, I became this guy who loved public policy, who figured out how to pay for all those public policies I’ve loved and I hold dear. So, I was able to arrive in the city of Chicago when I was recruited from the state legislature to work for Mayor Daly, but I really arrived in Chicago as this guy well-schooled in public finance and at the same time well-schooled in public policy.

[00:15:09] Paul: So, I think those traits, my understanding of what constitutes good public policy and my ability to really seek out the best policy approaches to deal with many of the governmental challenges while at the same time understanding the financial implications and figuring out how to pay for them. I, I think that’s a skill that I’ve always been able to bring to government. I think it’s been the key to my success.

[00:15:35] Charlie: Well, we may have to do another episode, Mr. Vallas, because I spent many months in 1992 in New York City working for Paul Tsongas’ presidential campaign. And I got to be very familiar with the whole Greek culture and Greek neighborhoods all around New York, and actually felt very comfortable coming from, myself coming from an Italian immigrant family. There are a lot of similarity there, so I really enjoyed it. But that’s for another day. You mentioned that in 1990 Mayor Daley recruited you to reform the then troubled Department of Revenue, revamp the city’s tax and fee system. When promoted to budget director, you ended the city’s recurring budget crisis, as you said the idea of coming up with the money to, fund the good ideas, and you simultaneously financed Chicago’s largest city infrastructure investment program in over a century. Could you share with us some of the big picture keys to understanding urban finance and especially how it impacts K-12 education?

[00:16:33] Paul: Yeah. Yeah. No, well, let me preface my remarks by saying in every single public service assignment that I’ve been given, I’ve always seemed to have gone from one crisis to another, really brought me up to reform the scandal over the revenue department, then of course I took over as budget director a year after has brought budget have been rejected, believe it or not, Mayor Daly. There was once, once upon a time. Yeah, rejected. and of course, I took over the [00:17:00] schools when they were on the verge of financial collapse and the mayor controlled the schools. So, I’ve always been kind of like a storm chaser, as my wife likes to say, but what I’ve discovered in each of my governmental undertakings is the degree to which there was so much waste and inefficiency, everybody that I, brought about this, miracle and, and taking the school district had a projected like five year billion dollars structural deficit and leaving the district six years later with a billion, almost a billion dollars in cash reserves and 12 bond rating upgrades among the largest school construction program in the country. But, believe it or not, it was not as difficult as one might think, in part because there was so much waste and inefficiency in the government institutions that I took responsibility for. So, I’ve always found, I’ve always found the situations much less dire than one would assume.

[00:17:52] Paul: And it’s because of the tendency in government to really misplace people, you know, to put people in public policy who may be more political than public policy experts to put people on finance who don’t really have financial experience and certainly don’t understand municipal finance because governmental finance, municipal finance is so different from, let’s just say private finance. So, so clearly the combination of politics and the lack of really competent people in critical positions have always contributed to those crises. So simply, you know, righting the ship begins with bringing the right people in and assigning people tasks and responsibilities that fit their talents and then trying to divorce the governmental entity that you’ve taken over from politics so that you can focus on what the long-term mission should be and needs to be. So, those crises have always been less challenging than people realize. That said and done,— my approach to budgeting has always been to introduce no budget no budget that is not a five-year budget plan. In government you need to bring continuity and stability to your agencies and to your departments. I certainly did that with the city. My approach was to basically provide all the department heads with five-year budgets and to assemble a budget that was structurally balanced over a five-year period.

[00:19:19] Paul: But to let those agencies know that what their money would be, what resources they would have available and that they would be fully supported in spending all those resources, in having the discretion to spend that money as they saw fit in pursuance of their mission, rather than be micromanaging and strangling them. Because when I was a city budget director in the revenue department, we would be given our budgets, there would then be delays in us getting approved for everything from spending to filling staff vacancies and then halfway through the budget year they would freeze our budgets. You know, so that budget director and the chief financial [00:20:00] officer could show that they finished the year with a balanced budget, despite the fact that the agencies had been all but starved.

[00:20:05] Paul: So, my approach, based on my experience, was to really give people there’s the line from the Rolling Stone song. You don’t always get what you want, but if you try real hard, you get what you need. What’s the work with them to get what we feel that they minimally needed. Give them that stability and flexibility so they would have a comfort level that this was the financial university had to operate with and then basically give them great flexibility to spend that money as they saw fit consistent with obviously the larger goals and objectives of the mayor’s office in that organization.

[00:20:40] Paul: I always felt in every place that I’ve gone that that type of budgeting approach was highly effective and it enabled me to basically balance, structurally balance my budgets while also getting the type of government productivity that had long been absent from those entities that I took responsibility for.

[00:20:59] Charlie: Well, you know, you mentioned how you have this history of coming in to deal with crises and that, that approach to governing is really, you know, the antidote to crisis, it takes away in many ways, I think, the ingredients of crisis by providing some predictability andall the things that don’t exist during a crisis. So, I think that makes sense.

[00:21:19] Paul: Well, you know, when it comes to things like public safety, look, we did two things. People don’t realize that in the nineties something dramatic happened in Chicago. There was a significant decline in violent crime, particularly the murder rate, the murder rate plummeted by like 60%, almost to New York levels. Not quite, obviously the dramatic decline in murders in New York was just unprecedented, like a decline in murders, but we went from almost a thousand murders to low 400s and even that is too many, but the bottom line is there was a steep and consistent decline. And the second thing that happened, obviously, because that period from really 1995 or 1992 to 2002 really covers my, my period as budget director in Chicago public schools. During that same period, particularly ‘95 to 2002, there’s a reversal in school enrollment, an enrollment that had declined over the previous 15 years by 115,000 suddenly reversed itself. And there was a growth enrollment of about 35,000 to 40,000. Of course, since then, it’s declined again.

[00:22:35] Paul: Well, what happened during those periods of time? A couple of things. First of all, we embarked safety strategy that focused on what we call community-based policing, where you would basically have enough officers to provide beat integrity, to respond quickly to 911 calls, to be proactive in terms of going out and making rush proactive within obviously within people’s constitutional rights. Proactive police means responsive policing. Incidentally, we didn’t have stop and frisk. So, but there was consistency. There was consistency. The resources were there. They knew it. The police commanders have flexibility. because primacy was given to having beat cops who knew the beat, who walked the beat, who was there, who knew the community, who in turn were known to the community to trust levels.

[00:23:26] Paul: We were able to significantly contribute to — we were able to really reverse the tide that had seen violent crime rising. The second thing was the schools. We really made the schools part of orr public safety strategy. And what we did was we opened schools through the dinner hour, on the weekends, over the summer, during the holidays, we really turned the schools into community schools and we brought community-based activities to the schools, faith-based partnerships.

[00:23:55] Paul: We used to joke that we didn’t do one church, one school, we did two church, one schools [00:24:00] and one synagogue, one school. The bottom line is, community-based organizations offering their programs in schools setting up parent and community centers in school. So the parents had a presence. So, the schools became a part of the game. And that, of course, not only led to significant improvement from an academic standpoint, but you saw a significant increase in enrollment after a period that had seen plummeting record declines in enrollment. So, you had this phenomenon of dramatic decline in violence in violent crimes, particularly murders and dramatic increases in student enrollment and consistent and steady improvement in academic performance. And I think it was a direct result of the policies that we put in place, but not only bringing stability, laying out a public safety strategy that was community based and then staying with that strategy for an extended period of time, but also with respects to the schools, really embracing this community school model and really transforming the community, the schools, into community centers that could offer a whole array of activities and services. In support of the children and their families, and I think it translated into a real renaissance for Chicago during that period of time.

[00:25:19] Charlie: Right. Well, let’s talk a little bit more about the schools. You know, urban school reform has been a big focus of K-12 education policy for, half a century. But nationwide, it’s really only experienced uneven success, particularly with stubbornly persistent achievement gaps. Would you go into a little more detail about the thorny politics of running the Chicago public schools, which it’s of course, the third largest district in the country.

[00:25:45] Paul: Well, I think what’s happened to the Chicago public schools has really been seen nationally. And I think COVID brought out the worst in, just how archaic and how almost obsolete this traditional system of public education is with its top-down, centralized management, with its mandates upon mandates upon mandates, particularly the collective bargaining mandates that somehow have nothing to do with providing quality instruction.

[00:26:10] Paul: I think what you saw in the ‘90s, and it really begins with early in the Clinton administration, was suddenly education became a positive. Obviously, we were doing a lot of innovative things in Chicago Public Schools for better or for worse, that drew a lot of attention, like ending social promotion and extending the school day and the school year and obviously introducing charter schools.

[00:26:31] Paul: but I think what, what happens in the ‘90s is suddenly public education educational reform becomes a political plus and for both Democrats and Republicans, by the way. You know, David Osborne, the Progressive Policy Institute emerges in the ‘90s. So, they’re strong advocates of public schools of expense, public school choice. And then, of course, that was followed by George Bush and George W. Bush and Race to the Top. And then of course the Obama administration with Arne Duncan, who incidentally was my deputy chief of staff in the Chicago public school. Okay..

[00:27:04] Charlie: Yeah, that’s right, another Chicago guy.

[00:27:04] Paul: Right. Who continued those reforms under Race to the Top. And as you know, as late as, 2012 states standing in line to, to amend their school codes to allow for the easier closing of failing schools, more teacher accountability remove the obstacles to charter school. So even as, Illinois State. Really, as late as 2011, 2012, the school reform movement is moving, maybe at an uneven pace, but there’s a push for more school choice. There’s a push for more accountability, et cetera. Certainly it was not without its challenges. Hiccups perhaps the overreliance on high-stakes testing and things like that. They certainly made a lot of mistakes, but they were making progress. What happens around 2010-2011 is the national teachers unions begin to realize that they’re losing ground. Charter schools are emerging a big choice for the expansion of public school choice. The power of the unions over the individual schools begins to diminish. So, they adopted the political strategy that they were going, they needed allies and it began to wrap themselves in the flag of a progressive movements.

[00:28:20] Paul: They began to align themselves with the progressive left, particularly the far left. They began to look for allies, and in Chicago, they certainly did it at the national level with Randy Weingarten, you saw it happen with the L.A. Teachers Union. You certainly saw it in Chicago. These far-left organizations, the anti-police organizations, the defund the police organizations, they’re all heavily funded and supported by the Chicago Teachers Union.

[00:28:44] Paul: They become the bank. So I think what they did was union leadership because they were trying to hold on, decided that they needed allies. So, they began to, and they, they needed to wrap themselves in the banner of the progressive movement. and, if you can identify anything as being anti-progressive, if you define progressive, because remember, it’s progressive, that means the first part of that term is progress, there’s nothing more anti-progress or antithetical to progress than the national teacher unions, just in terms of their opposition to any serious school reform or accountability.

[00:29:23] Paul: So, that’s what you really saw emerge. So, the unions really became the bank, they became chief funders. If you look at Illinois right now, I mean, they are among the biggest funders. There’s not the bigger funders the Democratic party. I mean, the amount of money that they spent supporting candidates, the amount of during COVID and the George Floyd tragedy, they were one of the biggest funders of Black Lives Matter of the defund of the police organizations were all funded by the Chicago Teachers Union. They were actively involved in their marches. They were demanding the defunding of the police, getting police officers who are in the high schools to deter active shooters removed from the school campuses. Well, at the same time during COVID, they were shutting down the schools for 77 consecutive weeks, so they really became you saw a reflection of the damage that they did not only from an academic standpoint, but you also saw during this period historic increases in violent crime committed against children, school-age children who attend public schools, but also the historic increase in violent crime by school-age children who were enrolled in public schools. And so, during that period of time, the unions emerged as a real political powerhouse and they were advocating for policies that were detrimental to the community as a whole, both in terms of blocking the schools from reopening long after the science indicated they could be reopened safely.

[00:30:55] Paul: And, of course, becoming the bank, so to speak, for many of these anti-police, defund the police organizations. In fact, the unions, the Chicago Teachers Union, actually working through their surrogates, not only were they able to effectively get the state to keep charter schools closed during COVID, even long after the CDC and the science that it was safe to reopen those schools, but they’re also we’re working through community-based organizations to try to force the Catholic schools to close, because they simply didn’t want schools to be open while the traditional union-dominated public schools were shut down.

[00:31:30] Paul: So, they really did significant damage and, really what’s happened in cities like Chicago, many of the large urban cities. It is the teacher unions have ceased to really become organizations that represent their members and to a great extent, they’ve become political organizations. There’s been all sorts of stories that talk about the overwhelming amount of the teacher union dues that are actually not going to provide for services to the members, but are actually making their way into the coffers of political campaign. So, so really the national teachers’ unions and their local chapters, their local affiliates they become almost like political parties in their own right. And so they’re, beginning to focus on issues that, are a progressive agenda that goes far beyond just where the focus should be providing quality educational opportunities for working families and poor families.

[00:32:22] Charlie: Yeah, you know, it’s interesting. And I know that the Chicago Teachers Union is really on the vanguard of this kind of radicalization. It’s interesting because here in Massachusetts there was just the big interview with the head of the Mass Teachers Association, who really was very open about this transformation of his organization from just talking about the schools to really being an advocacy group for this sort of larger, you know, what he would call a progressive vision.

[00:32:51] Charlie: And it’s just, you’re right, it’s been a very interesting and very fast change. You talk about how different it was just as recently as 2012. So, yeah, no, I think that’s absolutely true. You know, you talk about the impact of teachers’ unions and how they’re changed in some ways become more powerful. What’s your advice for having to work with them and, negotiate with them? Or, was your position or were you negotiating with them largely before these changes took place? What are your thoughts on that?

[00:33:23] Paul: I’ve worked with teacher unions in five different cities, including New Orleans where, you know, all the schools in New Orleans with exception of the select enrollment schools, which incidentally remain traditional public schools, all the open enrollment schools, general enrollment schools, to enable schools are in effect, charter public charter public, not-for-profit charter schools, charter schools, public schools, charter schools are not for profit. Only one state allows for for-profit charter schools, and that state is Arizona. So, you know, so it’s they’re just non-union. So, the union likes to claim that charters are privatization. It’s just a bunch of hogwash. But the point that but I was able to negotiate contracts in five different cities. I never had a delay in getting contracts done. I always raise teacher salaries in Chicago and in Philadelphia, I had a good relationship with the teacher unions there. I respected them. I was accommodating. They understood where I was coming from on school accountability and the need to transform their schools. They allowed me to have a lot of flexibility.

[00:34:32] Paul: I, in turn, respected them and really brought them into the process and, but that kind of predates this big change that begins in 2009-2010. When I went to Connecticut to my last district, that was kind of post that period, I had a rougher time with the teacher union. It didn’t keep me at all from opening schools on time and negotiating the collective bargaining agreement. It’s certainly made it difficult for me to, to make other broader changes, but clearly I think the unions, the teacheers’ unions across the country have become radicalized. I think what’s happened since COVID because COVID really showed. I mean, sometimes it takes crises to bring out people’s strengths or, or the strengths and the weaknesses of institutions as well as individuals.

[00:35:15] Paul: And it certainly showed just how incapable or how ill equipped the schools are for dealing with the crisis. I mean, it was clear that charter schools had done far better as did private schools. Reopening even before reopening, providing online education their flexibility, their ability to prioritize without being handcuffed by these collective bargaining mandates, they were clearly much more nimble in responding to COVID.And I think it was reflected in the fact that during this post-COVID period, you saw the biggest increase. in charter school enrollment in in probably 10-15 years, as well as a private school enrollment while you saw corresponding decline in traditional public school enrollment. So, clearly, this period just revealed the flaws, basically how ineffective that system is, and it’s not like a — and the crisis really brought out for all to see just how unresponsive and how ill equipped that system was to provide educational services for the children during that critical time. And I think it was a great awakening, but rather than adjust or accommodate, they’ve actually dug in. You know what I mean?

[00:36:30] Paul: I mean, look, post-COVID there’s been three work stoppages in Chicago. Look at LA with their threatened work stoppages. I mean, unions are digging in and the reason they’re digging in is they’re digging in with their money, they’re digging in with their clout. I mean, the Biden administration, what they did with the second COVID relief package, the Biden administration, first of all, during the first COVID relief package, the money really was allocated based on where the kids were. So like private schools got 10 percent of the COVID money in the last election. in Biden’s in the school funding components of, Biden’s COVID relief legislation, I think private schools got 2.2 percent. And of course, that money was allocated and had so many strings attached that it really targeted a certain number of schools rather than being money that was allocated you know, across the private K-12 school world based on student enrollment. So, at the end of the day you know, the unions have been digging in even more despite the fact that they’ve been losing ground when it comes to enrollment when it comes to popular support, they’re still digging in because they have such a stranglehold, because they have become so political in terms of their fundraising capabilities and their ability to organize and to, in effect, put boots on the ground and participate actively in, these local campaigns. So if anything, the unions are digging in, they’re not adjusting.

[00:38:02] Charlie: Yeah, You’ve really brought up what I think is a very interesting dichotomy here, which is that, you know, you’ve got a situation in which, particularly with the pandemic, more and more students are opting for charter schools, opting for private schools, opting for homeschooling, you know, whatever the option is, and leaving public schools. Public school enrollment is down. Yet despite that, despite the sentiments of parents, the politics seems to be moving in exactly the other direction, as you say, not only are the teachers unions sort of doubling down, but it’s related to that. You have a lot of President Biden, a lot of other Democratic leaders are, doubling down as well.

[00:38:43] Paul: Yeah, yeah, I, but well, you know, and it’s again, I think because you have to ask yourself, when is the tipping point going to be reached? I think where people have just basically have had enough. It began to happen with COVID but the problem in the school choice community is, the school choice community needs to take a page out of the traditional public school community the union-dominated traditional public schools, and they’ve got to organize. They’ve got to build a coalition. So, for example, there’s tension between parochial schools and charter schools. Yeah. Many charts will see parochial schools as the enemy. Many — I remember I offered Cardinal Francis George when I was. It’s my heyday in the Chicago public schools and I have full support of the mayor and we had a great relationship with our teachers’ union. We negotiated contracts, opening schools in time. And when the archdiocese was considering closing 50 schools, I offered them a charter to bring all those schools under a single charter so that they could stay open because closing schools in those communities I felt would, would hurt those communities overall and what people don’t realize is the heyday for charter school enrollment or for public school enrollment in Chicago was also the heyday when public school enrollment was at its peak and vice versa. You know what I mean? The more school choices, the stronger the community. And, of course, the cardinal turned me down, because of their opposition to charter schools. So, I’m building a coalition among those who advocate for school choice. You see, school choice is a constitutional right as a civil right. I mean, bringing the parochial school and private school communities together and then seeking allies. Within the American labor movement, because so many, so many of the public employee unions do not send their kids to public schools. In fact, in Chicago, 40% of the teachers don’t send their kids to public schools. They send their kids to private schools. In fact, the union leaders and prominent union members either send their kids to private schools or they send their kids, or somehow they won the lottery, have their kids in select enrollment magnet schools. Okay. So it’s, you know, it’s like what’s good for the goose is not good for the gander, so to speaker.

[00:40:58] Charlie: Do as I do.

[00:40:59] Paul: Yeah, exactly. So, I think what’s really critically important is, is that those who believe that parents should have the right to pick the appropriate school for their child, whether it’s a public charter, traditional, or for that matter private, and those who believe that communities through their elected local school councils should have the ability to demand a better school model, even if that means they replacing existing school model with a charter school model — like they do in Camden and Denver and Indianapolis with great success. Yeah, Renaissance schools. Those who believe that need to come together as part of a broad coalition, strengthen numbers, you know what I mean?

[00:41:40] Charlie: Just to add to that, I think they need to sort of lose this view that sort of politics is below them. Yeah, you know, you know,

[00:41:51] Paul: Look, even among even among some of the big charter powerhouses, it’s like they become very insular. You know, they’re not out there, they’re collaborating with other charter providers, you know, they’ve got their little university got their network of funders. they have their schools. They kind of sometimes handpick where they’re going to open their charters or allow conditions on what opened their charters. So, they’ve got their own protected universe. And sometimes for some of them, it seems like they could give a damn about what happens to other charters. So, you’ve got to unite the charter community. And you’ve got to unite the school choice community, and the school choice community has got to find allies, they’ve got to reach out to community-based organizations and faith-based organizations and the unions who are mostly, who are perhaps significantly adversely impacted by the lack of quality public education choices because you know, if you live in the city of Chicago where — whether you work for the schools or whether you’re a police officer or firefighter or work for any city department or city agency or other governmental agency that’s controlled by the mayor — you’ve got to live in the city. That means you’ve got to send their kids to public schools, or you have got to pay a small fortune and send your kids to private parochial schools. One would think that some of those unions are ripe for building alliances with, particularly some of the unions, some of the non-education-related unions, whether it’s the trades, whether it’s police, fire, whether it’s the operating engineers, et cetera. Well, there’s the hospitality. One would think that that it would be in their interest to want to see quality educational choices. They would want to see their members have the ability to pick better schools without spending more and more of their disposable income to pay for their child’s education because the public schools are so woefully inadequate.

[00:43:43] Charlie: Right. Speaking of school choice, in your recent marital campaign, you pledged a hundred percent choice to parents as to what schools their children would attend, and you focused on the concerning rise in youth crime rates and gun violence. Would you talk about the connection between education reform and parents having school choices and how they impact the growing sense of despair among young people in American cities?

[00:44:04] Paul: The challenge that we face is, without competition I think the quality of education languishes. Languishes, you know, because people, there’s just no pressure. There’s no accountability in the Chicago public schools right now. They’re really working overtime to do away with standardized testing and they returned to social promoting. So, they’re back. I mean, 84 percent of the high school kids last year graduated high school, despite the fact that only one in four are reading at the national norms, only one in six are computing at the national norms, and only 6 percent of the black kids who had a 79 percent graduation rate, by the way, 6 percent of the black students meeting state and national standards and math.

[00:44:45] Paul: I mean, that’s, that’s a disaster. That’s an absolute disaster, but yet there being so, so there’s no accountability. There’s no accountability teachers in Chicago public schools. Last year, every teacher was rated as meeting standard. There was not one teacher that rated as non-performing or so every teacher, every teacher got a passing grade.

Charlie: And of course, like Lake Wobegon

[00:45:06] Paul:. Yeah. and finally, they want to stop ranking schools by academic performance. They now want to look at other factors, even, you know, I mean, there are 50 schools in the state of Illinois that don’t have a single student at grade level yet. Wow. Really? How many of those schools have been reconstituted or closed? In Chicago, You have just dozens and dozens of schools with single digit test scores. So, there’s no accountability because they’re not going to count those things. So, what they’re doing is they’re trying to erase the scorecard. They’re trying to erase anything that measures the school’s success at its core mission, and that is teaching children, providing them with the academic skills that they need to be effective, to graduate from high school with a diploma that they can read with the academic credentials to to get into college or to get into some sort of occupational training program that can help them select a suitable career. And they’re simply not doing that.

[00:46:12] Paul: So, what they’re doing is they’re running for cover. So, parents are really denied choices. Now, some have argued that, well, you know, even if you gave parents choices, would they make the right decisions? Bottom line is, in the city of Chicago, there are 54,000 students who attend charter schools, 54,000 who attend public, not-for-profit charter schools. 96% of those children are black and Latino, and 80 percent are poverty — 96% percent! Clearly, there are parents, there are poor parents out there, that are frustrated enough with traditional public schools and concerned enough about their kids that they’re navigating the charter waters or the charter application process. And the city imposes all sorts of — they’re always throwing obstacles in the path of charter schools and charter school applications, but clearly they’re concerned enough about their charter education about their child’s education, that they’re, they are seeking the right school for their kid. And so, I believe the more choices you provide, the more quality choices you provide, it provides a vehicle to engage parents. And of course, many of these charters, have schools that are open, that have a longer school day. They have a longer school year. They require a certain level of parental engagement. They hold the kids as well as the parents to higher standards. And those are all good things. So, I think it’s like if you build it, they will come. And I think that’s the approach that you have to take. If you provide options to parents, you empower the parents, the parents will become more engaged.

[00:47:44] Paul: That in itself, can have a positive impact on parents and compel parents to take, to play a more aggressive role in the education of their children. Likewise, if you empower the community, if you empower the community and through the community, they’re elected local school councils to decide to go out and seek and secure a better model. For their neighborhood school that can suit and address the needs of that community, if you empower that community in that way, that in itself will embolden the community. That in itself will help the community develop and grow. You see what I mean? So, in absence of power, people become frustrated. People become complacent. They become hostages with no way out, whether it’s individual poor families or for that matter, the community as a whole. So, through school choice you have community empowerment. Through school choice, you have parent empowerment. And that’s how you can get the parents, and that’s how you can get the communities more engaged in the education of the children.

[00:48:46] Charlie: Well, Paul Vallas, you have given us a whole lot to think about here today, and I think made some really compelling points. Thank you so much for making the time and joining us. This is a real pleasure. I really appreciate your coming and being part of the [00:49:00] Learning Curve.

[00:49:01] Paul: Well, it’s my pleasure. Thank you, and I would love to come back at a time convenient.

[00:49:06] Charlie: Great. Well, we’d love that. You’re on. Thank you so much.

[00:49:09] Paul: Well, thank you for having me. Bye bye.[00:50:00]

[00:50:19] Charlie: Our tweet of the week — chose one from Education Week. You know, I think that all of us know, two things. One is that many of our school districts are facing a fiscal cliff as the pandemic money kind of runs out. And the second one is the fact that, quality tutoring is one thing that has been shown to really work and help students, particularly low-income students, you know, the students Mary mentioned, you know, low-income students, English language learners, special needs students. Anyway, so the tweet was from Education Week saying that schools may lose more than $1,200 per student as enrollment falls and federal COVID relief funds expire next year. It points out three steps to keep tutoring going when ESSER money runs out. And I think this was from September 4, and I think it’s really one that’s worthwhile as school districts are going to face these real challenges in the near future.

[00:51:14] Mary: Absolutely, Charlie. And one of the things we’ve seen, and we’ve certainly seen this here in Massachusetts, is a drop off in public school enrollment. And so, districts are going to be faced with some really hard decisions as this, you know, additional federal funding goes away. And I know again, you know, using Boston as a lens that, they are so under-enrolled at this point that the number of empty seats could fill up almost 17 schools in Boston, and it has very expensive to run schools that are not only half empty, but some of them are two-thirds empty. And so you have mayors and city councils that are going to have to make some really tough decisions about how to streamline the number of buildings they operate, their operational models — because we will never be able to. invest in the students we have if we continue to pay for the students who have left our schools.

[00:52:13] Charlie: Well, Mary, you very innocently — as the people here will tell you — you very innocently just walked into something that is one of my obsessions, which is the need to right size the district. But I will out of respect for you and our listeners, I will spare you from my usual screed about that.

Mary: We’ll, we’ll save that for next time, Charlie.

[00:52:30] Charlie: That’s right. That’s right. But I think you make a, very, very good point. You know, here in Massachusetts, we just saw what I hope will not be sign of court, a, a kind of a sign of, of things to come, which was in Brockton, which is a city south of Boston, a city of about 100,000 people that just recently discovered that it had at school year’s beginning that it had a $14 million shortfall from the previous school year. So as I said, hopefully that is not a sign of things to come.

[00:53:03] Mary: That’s right. And they just actually prior to the discovery of that shortfall, they had a significant layoff of teachers as well. And so, Brockton has been the small city that could, you know, at a time when the Gates Foundation was funding, you know, large comprehensive high schools into smaller communities of learning, Brockton was one of the few that resisted taking that money and going for that model of smaller learning academies and thrived as a result. They actually, I remember the New York Times did this great story about the success at Brockton High School and it’s really a shame to see them going through what they’re going through right now.

[00:53:43] Charlie: Yeah, it really is. Well, Mary, it’s been a pleasure to work with you this week and to get talk to Dr. Vallas. Thank you very much for joining us. Next week, we’re going to have Ramachandra Guha, and he’s the author of Gandhi Before India and Gandhi: The Years That Changed the World, a two-volume biography of Mahatma Gandhi. So again, thank you very much, and I look forward to maybe doing this again.

[00:54:11] Mary: Thanks, Charlie. I, I hope we can do it again sometime.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Charlie Chieppo and Mary Tamer, executive director of Democrats for Education Reform, Massachusetts, speak with Paul Vallas, former CEO of the Chicago Public Schools and a candidate for mayor of that city earlier this year. Vallas talks about the professional lessons he drew from public leadership, how he financed the largest infrastructure investment program in over a century in the city, and how he closed deficits and balanced budgets as head of the Chicago Public Schools. He also reflects on Chicago politics, the challenge of bargaining with teacher unions, the state of charter public schools in Chicago, and the growing political power of teachers’ unions in large urban areas.

Stories of the Week: Charlie discussed a story from Education Next on innovation and success in charter public schools in Indiana. Mary commented on a Boston Herald article about the Massachusetts Teacher Association’s ongoing efforts to end the state’s MCAS tests as a graduation requirement.

Guest