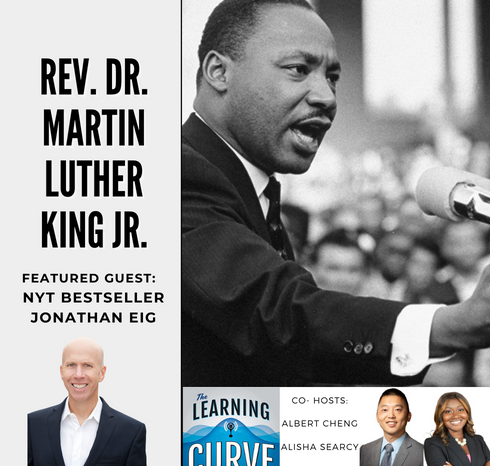

NYT Bestseller Jonathan Eig on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

TRANSCRIPT

The Learning Curve Podcast

Jonathan Eig on MLK

January 15, 2024

[00:00:24] Albert: Well, hello everybody and welcome to another episode of the Learning Curve podcast. I’m your host, Albert Cheng, from the University of Arkansas. Co-hosting with me today is our friend, my friend, Alisha Searcy. Hey, Alisha, how’s it going?

[00:00:37] Alisha: Hello, Albert. Wonderful. Great to be with you again.

[00:00:41] Albert: Yeah, that’s right. And happy Martin Luther King Day. We’re meeting here to broadcast this episode to commemorate that. And yeah, we’ve got an exciting guest, Jonathan Eig, who’s the author of the definitive biography of Dr. King. And so, we’re looking forward to sitting down with him and learning more about his life.

[00:01:01] Alisha: I live in Atlanta, so, you know, clearly, I’ve interacted with the King family and know a lot about his history, but I’m very interested to hear more and learn more. I think her was, King was such a fascinating figure in a lot of ways. So, I’m very much looking forward to this and of course celebrating his birthday and his legacy.

[00:01:22] Albert: Yeah. Yeah. Well, first up some news and maybe just speaking about reform — you know, this is not civil rights reform necessarily, but education reform — I want to point out an article in Education Next written by Sue Walsh, it’s actually a piece written in memory of Linda Brown. And so, in case listeners aren’t familiar, Linda Brown was a major school reform figure particularly in Massachusetts, but also nationwide. Years ago, in the early days of the charter movement she started the Charter Resource Center here at Pioneer which eventually became the Building Excellent Schools initiative that she managed and ran for many years training — I don’t know what — it’s hundreds of charter school leaders across the country! The article referred to her as the Yoda of the charter school movement. And really, she trained a lot of the school leaders, the other Jedi, I guess, if you will. A lot of thanks goes out to her. We really wouldn’t have a lot of the excellent charter schools that are out there today if it weren’t for her. So, really want to recognize her passing. Happened last year on Christmas Day, actually. I just want to point listeners out to learn more about her life and legacy at the article at Ed Next.

[00:02:32] Alisha: Absolutely. And we thank her for her work. I remember when she passed Dr. Howard Fuller, who’s a mentor of mine, tweeted about it and what a force she was. So, we are grateful for her work, and I happen to lead a couple of the schools of the founder who went through BES. So, her legacy is tremendous and spans across this country. And so, we thank her for her work and her legacy. And I can only imagine how difficult it was for her, at the start of all of this. And so, I don’t think it’s an accident that we’re talking about her work and the trails that she blazed on Dr King’s birthday. I’m one of those people who believe that education is a civil rights issue, and so, it’s important to acknowledge those who have sacrificed and done a whole lot of work to help us get to where we are.

[00:03:23] Albert: Yeah. Yeah, that’s absolutely right. The charter school movement is just over 30 years old. You know, 30 years is about the time period for a generation. So, we’re always looking out for the next generation of leaders in the school reform movement.

[00:03:35] Alisha: That’s right. Step up, because we need you!

[00:03:38] Albert: Yeah, that’s right. Well, what have you got on your docket for, in terms of news?

[00:03:42] Alisha: So, very interesting story. Utah has no plans to change the lowest-in-nation education spending, officials say. And this is a piece from the Salt Lake Tribune. And so, Albert, we all know this ongoing debate about “we need more money in education. If we just had more money, we could just fix everything.” And I do not subscribe to that philosophy. I don’t think we have a money problem in education, I think we have a priority problem. And so, this article is very interesting. So, a few facts that I learned, I didn’t know this about Utah. They remain one of the lowest education spending states in the country and were the lowest for two decades until 2021. And now they’re 49 only bested by Idaho which is now the lowest in the country. And so, we’re talking $9,095 per student as compared to the state of New York, whose average per-pupil spending is, get this, $26,000. And I’m not picking on New York, there’s obviously economies of scale and all of that. And I’ll talk about poverty in a second. But what’s interesting here is that despite Utah being one of the lowest in the country in terms of spending, they’re actually outperforming other states who spend a lot more in some of the most critical areas.

[00:05:06] Alisha: So, for example, in math, Utah is tied with Massachusetts, which, by the way, spends more than double what Idaho does. And they have the highest percentage of eighth graders scoring above proficiency as of 2022. Same thing. And they’re number five when it comes to fourth graders scoring above proficiency in math, and similar numbers for fourth and eighth grade in terms of leading in the country, in the top 10.

[00:05:31] Alisha: And so, I think it, again, begs the question. But before I got too excited, I realized that Utah doesn’t quite have it all together. It turns out that less than half of their third graders are reading on grade level. So, they’ve got some work to do. The good news is they are going to be spending, I think it’s $11 million out of their $1 billion of COVID funding to focus on literacy.

[00:05:57] Alisha: The question is, when you identify what the problem is, how do you direct those resources in the right place for the right reasons for the right people. So it’ll be interesting to see what happens, but at the end of the day I think it’s important to have these conversations about the impact of funding. The last thing I want to mention that can’t be lost in this conversation is the rate of child poverty. Can I ignore the impact that poverty has on educational outcomes? It’s not an excuse. I’m not one of those people who believes it’s an excuse, but you do have to acknowledge: If a student doesn’t have a home, if they didn’t eat this morning, they’re probably going to have a challenge learning. So, when you look at Utah, they have an 8 percent child poverty rate compared to Georgia where I live, it’s 20 percent. And so that makes a difference, interesting article. I appreciate it. I think it’s an important conversation that we need to continue to have, and we need to decide, I think as a country and as states, how do we get the biggest bang for our buck so that we can compete lik eUtah, and our states can all be at the top. And it’s not about the money, but it’s about our priorities and how we best spend those dollars.

[00:07:10] Albert: Well, yeah, this is the perennial question in education. How do we use our resources well and deliver it to the students and families that need it the most. And, you know, at the same time, how do we set up policies and build institutions that support children and their homes and their families? There’s a lot to the big picture here and it takes all of us and it takes all of us. So, let’s see what happens in Utah. And in the meantime, stick with us coming up after the break. Again, we have Jonathan Eig, who’s going to sit down and chat with us about Dr. Martin Luther King.

[00:08:07] Albert: Jonathan Eig is the best-selling author of six books, including his most recent, King A Life, which was nominated for the National Book Award, and the New York Times hailed it as the definitive biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Jonathan’s previous book, Ali: A Life, won a 2018 Penn America Literary Award, and Esquire magazine named it one of the 25 greatest biographies of all time.

[00:08:35] Albert: He also served as consulting producer for the PBS series Muhammad Ali, directed by Ken Burns. Jonathan’s first book, Luckiest Man, The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, reached number 10 on the New York Times bestseller list and won the Casey Award. His books have been listed among the best of the year by The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, and translated into more than a dozen languages. Jonathan appeared on the Today Show, NPR’s Fresh Air, and the Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He studied journalism at Northwestern University and went on to work as a reporter for the New Orleans Times Picayune, and the Dallas Morning News, Chicago Magazine, and The Wall Street Journal. He lives in Chicago. Jonathan, it’s really great to have you on the show.

[00:09:20] Jonathan: Thank you. It’s good to talk to you.

[00:09:24] Albert: Let’s start with a couple questions about some of Dr. Martin Luther King’s background and influences. So, as we celebrate his life and legacy and in your definitive biography, king of Life you emphasize his deep faith as a Baptist pastor. So, could you talk a bit more about that? Share with us what we know about. His role as a young spiritual leader and preacher in Montgomery, Alabama especially during the largely female-led bus boycott from 1955 to ‘56.

[00:09:52] Jonathan: You know, when you think about what made King the right person in that moment, well, obviously, a lot of things had to come together for him to be the leader of that bus boycott. And as you hinted, it was really the women who prepared for that moment, who had prepared for years and who organized the boycott. It was women out there distributing the flyers and urging people to stay off the buses. How does King become the leader? It’s because he is a preacher for one thing. And that gives him a position of authority in this very still sexist world and time in which he was living. It’s also because he’s new in town and he hadn’t made any enemies yet, but it’s really his religion that allows him to speak to this group and to unite people and to inspire people. He’s a preacher, he’s a son of a preacher, and the grandson of a preacher and he sees the Bible as something that’s in conflict with American society, and you know, the black social gospel says that the job is to bring those things into alliance, into harmony, that it’s the job of the church, it’s the job of preachers, it’s the job of Christians to change the world until people really are all equal in the eyes of God and in the eyes of their government too.

[00:11:02] Albert: Yeah, well, so, you know, speaking of preaching and, you know, you gave many, many speeches. I’m thinking of Langston Hughes, actually, just to get to another influence his famous poem “Harlem, a Dream Deferred. That poem strongly influenced Martin Luther King’s sermons and speeches about dreams. Could you just talk a bit more about his literary background about, you know, his knowledge of the Bible, scripture, history, founding documents, other poems, hymns, spirituals, like did those, some of those literary works influence him?

[00:11:33] Jonathan: You know, it’s important to remember that King was learning to preach before he could read, and he absorbed so much in his lessons he would travel the neighborhood and listen to different preachers. He would listen to preachers on the radio, and he would listen to poems in school. And it all went into this great mind of his, and it all churned around and came out in different ways. But he was really a borrower. It got him in trouble sometimes. He was accused of plagiarism and he was guilty of plagiarism. But I think he saw himself, again, as a preacher, which meant that he wasn’t so much worried about originality. He was focused on inspiring an audience. And if he heard a line from Langston Hughes and he could mix that with something from the Bible and mix that with something from the constitution, he was like a jazz musician, clipping phrases from here and from there and, imitating other jazz musicians.

[00:12:25] Albert: That’s an excellent way put it, fascinating way. Just as a jazz, a literary jazz musician, if you kind of mush those two together. Yeah. Um, moving on to, another important influence is his wife. So, you talk about Coretta Scott King a lot in your biography, they married in 1953 on the lawn of her parents’ house in her Alabama hometown. Had four children. talk a bit more about Coretta Scott King. you know, her background, what their marriage was like, what their family was like.

[00:12:51] Jonathan: I really felt like it was important to give her a more prominent role in this book. She is often, like a lot of women of her era, has been overlooked, assigned to this role as being the supporter. and we fail to appreciate just how important and how much of an inspiration she was. And, when King met Coretta, they were students, he was at Boston University, and she was at the New England Conservatory of Music. He was dating a lot of women. And you have to ask yourself, why Coretta? And I think it’s because she was an activist. She had a career already in activism. She’d been to Antioch, you know, an integrated white college. She’d been involved in all kinds of protest movements and King hadn’t done anything yet at that point. So, he thought that he could learn from her and that’s to his credit. He continued to learn from her. He continued to be pushed by her to be more aggressive, to think more globally about his role as an activist. He didn’t always appreciate that. He didn’t give her the opportunities that he should have. He was still, you know, mired in his own prejudices, but I think that Coretta really hasn’t been fully appreciated throughout the history of as we tell these stories.

[00:14:00] Albert: Well, so let’s get into some of the actual work and activism. As you note Dr King co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the late ‘50s and then played a secondary role in the Freedom Rides in 1961. and Southern Christian Leadership Conference also, I mean, they’re involved with the efforts at Albany, Georgia in ‘61, ‘62, but they were largely unsuccessful. Talk about this period of King’s work and the lessons that learned from the experiences at that time.

[00:14:31] Jonathan: You know, King was 26 years old when he became the leader of the Montgomery bus boycott. Like, I don’t remember that. I don’t even want to think about how little I was accomplishing at age 26. After that, he even writes to one of his college professors. What am I supposed to do now? I feel like I’ve peaked at 26. People are going to be expecting miracles from me, and I don’t know what to do. So, he tries and fails a number of times. We see him really struggling. He starts the Southern Christian Leadership Conference but doesn’t really have a plan for how he’s going to make it a success. He undertakes these movements in places like St. Augustine and Albany, Georgia, and they don’t go very well. It looks like he’s kind of defeated in these places by the white power structure. That he starts these protests, but it’s not really clear what he’s trying to accomplish. It’s not as simple as integrating buses, and he leaves those towns without really much to show for it. So King is adapting, he’s learning. You know, other people are now having some success with student sit -ins at lunch counters and on, on the buses, the freedom rides, as you mentioned. And King, to his credit, doesn’t try to take over those movements. He helps where he can. He’s showing some humility. He’s listening. He’s learning. And he’s trying to figure out how to make the next movement a success. So, it’s a really great moment to see young King learning and learning from his mistakes.

[00:15:49] Albert: Well, so speaking of all the other people involved in, the civil rights movement, it’s been noted that at times that it was Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference who are leading and other times it was students and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, for instance. You know, there were other civil rights figures — Diane Nash, Bob Moses. Could you talk about the relationship between Dr. King and the CLC and all these other entities within the civil rights movement?

[00:16:18] Jonathan: It was a challenge, you know, it was a challenge and an opportunity. So, you know, King comes along and out of nowhere After years of seeing groups like the NAACP really leading the way he’s a superstar and he’s attracting all this attention and he’s also kind of a threat in some ways to the establishment and by the time he’s 30 years old, he’s a threat to the NAACP in one way, but he’s also, too conservative for some of the younger activists. They’re starting to call him De Lord, as if he’s like, you know, high and mighty and out of touch with the young people in the movement. So, really difficult. King’s got to navigate a very difficult path. And I think that’s one of his great skills is that he’s a great listener. He’s open to learning from others. He’s not trying. To hog the spotlight. He wants to work with others. And, you know, even people like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael come away really impressed when they spend time with King, they go in skeptically and they come out really admiring. And he was just a great coalition builder in spite of everything.

[00:17:16] Albert: Well, we could use a lot of coalition building these days, too.

[00:17:18] Jonathan: Yes. Even a little would be good. Yeah.

[00:17:26] Alisha: So, Jonathan, thanks for being here. I’m very fascinated by your work. And as someone who grew up in the NAACP and learned a lot about these figures through the years, it’s quite interesting to get your perspective. And so, one of my favorite pieces of literature I will call in our history is the Letter from a Birmingham Jail. And so, I would love for you to talk about Reverend Shuttlesworth and how he worked to have the S.E.L.C. And Dr. King comes to Birmingham, Alabama for direct action and what many regarded as the most segregated city in the south, and to talk about what you know about Dr. King and his time in Birmingham and the participation of Reverend Shuttlesworth and the students and the protest there. And of course, the letter from the Birmingham jail.

[00:18:13] Jonathan: Thank you so much for asking that because, you know, Reverend Shuttlesworth does not get the attention he deserves. We should someday, I think — I predict we’ll see a movie and certainly another book or two written about him because he’s just such a fascinating figure and he’s a great example of how King is being pushed by people who want to put the pedal to the metal. They’re saying we’re not being aggressive enough. We’re not aiming high enough. And Shuttlesworth — after King fails in places like St. Augustine and Albany — Shuttlesworth is saying come to Birmingham. Birmingham is the most racist city. They call it Bombingham because, you know, there’s so many bombs going off. White people are blowing up black churches, black homes. Shuttlesworth’s home was destroyed by a bomb. It was a miracle that he survived. And, you would think King might say, why would I want to go to the most difficult, most dangerous place?

[00:19:02] Jonathan: But that’s a testament to, you know, the persuasiveness of Shuttlesworth, but also to the understanding that King has of his role. That his role is to shine a light on America’s racism, its discrimination, to show the world what black people are facing, especially in the Deep South at that point. And he goes to Birmingham knowing that it’s going to be difficult. And, he would say afterwards, or, you know, some of his supporters would say afterwards that they had this Operation C for Conflict their plan was to stir a conflict, but they did not have a plan going in. They only said that afterwards. Their plan was to just go in and see what happens. And that’s what makes it so powerful. That’s why the letter from Birmingham jail is so powerful because it’s a spontaneous act of passion and protest.

[00:19:49] Alisha: Wow. Very powerful time. So, in 1963, 250,000 demonstrators marched to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where Dr. King gave his famous — now we know as “I Have a Dream” speech. And then a year later in 1964, he won the Nobel Peace Prize. Can you talk about these events and the famous speeches Dr. King delivered at those?

[00:20:12] Jonathan: The March on Washington is King’s most famous moment. Of course, we all know “I Have a Dream.” Every kid learns it in kindergarten now. But it’s important to remember that he didn’t plan to give that part of the speech. What he planned to say and remember also that it was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. What he wrote in the prepared portion of that speech, and what he delivered in the prepared portion of his speech, was a really harsh criticism of America and its debt that it owed the people whose families, whose ancestors had been enslaved. He talked about the fact that. There was a moral reckoning that needed to be made, that a check had been written and it had come back with insufficient funds. America would not be able to move on until it atoned for the sin of slavery. He talked about police brutality in that speech. That was, you know, the speech he intended to give. And we forget about that part because he gave this beautiful sermon at the end where he improvised and talked about his dream. And in some ways, it overshadows what was really important about that speech. But that having been said, you know, the “I Have a Dream” part of the speech really was beautiful and inspiring, and it made a lot of people, in particular white Americans, feel like, wow, we can change. Maybe we can do better. That was a moment. It was a moment where I think America looked like it might finally turn the corner.

[00:21:32] Alisha: Maybe we could stand to hear that one more time, right?

[00:21:35] Jonathan: Yeah, no question. But you know, part of the problem is that there’s always a backlash. And the people who don’t want to see change react to that. And you see a couple of things happen right after the March on Washington. You see the FBI produce a memo that’s saying because of that speech, because of King’s power to unite black and white Americans, we must view him as a threat, the greatest threat in America right now when it comes to race. You know, how sad is that? And then of course, soon after that memo is written, we get the bombing of the church in Birmingham with these innocent little girls are killed. And that’s because members of the Klan, white racists in Alabama, don’t want to see King’s dream fulfilled. And they’re going to do everything they can to stop it, including murder.

[00:22:22] Alisha: When Americans think about Dr. King and the civil rights era, they most often remember events in the American South, but Dr. King said his 1966 Chicago campaign was among his worst encounters with racism. Can you talk about Dr. King’s life experiences and how they differed in Northern and Southern cities?

[00:22:42] Jonathan: Yeah, that’s a really important subject too. It’s worth noting that King was talking about Northern racism, really his whole career, when he would travel to raise money in places like New York and Chicago, he would call out their own problems. He would say, yes, I’m fighting it out in Birmingham, I’m marching in Selma, but don’t forget you’ve got segregation here in the North too. You’ve got discrimination in hiring and in housing here, too. And by the time a little bit later, by the mid-sixties, he starts to focus his attention on that.

[00:23:11] Jonathan: He says it’s not enough anymore to work on desegregation in the South and voting rights. He would be hypocritical if he didn’t take action. And that’s why he begins to focus on the North. He moves to Chicago — my hometown in 1966 — moves into an apartment in North Lawndale. And tries to call attention to the fact that so many poor people in Chicago, and in particular poor black people, are living in these really dehumanizing conditions, and that landlords are making money on the poverty of their tenants, and he really wants to the nation see that this deeply ingrained racism affects the whole country, and it doesn’t go so well, you know, the media doesn’t like it.

[00:23:54] Jonathan: Northern politicians really just do their best to get him out of town and hope that he’ll go away. And King doesn’t get the kind of results that he’s looking for. And he begins to lose popularity. He begins to lose effectiveness. By 1967, I think 35 percent, only 35 percent of Americans said they approved of Martin Luther King’s tactics in Gallup polls. And he was getting frustrated. He felt like people weren’t, didn’t want to listen when he talked about Northern racism.

[00:24:19] Alisha: The epitome of leadership is hard and lonely, right? Doing the right work, but not very popular.

[00:24:26] Jonathan: That’s absolutely right. And I do think, you know, he felt lonely. I think he felt sad. We have the transcripts of his phone calls because the FBI was taping his calls and bugging his hotel rooms. And we can read what he was saying in his private moments to his friends, to his closest friends and allies. And he was depressed. He felt like people had given up on his dream and that it was turning into a nightmare. It’s really sad. It’s heartbreaking to read those transcripts.

[00:24:52] Alisha: Wow. I didn’t know that. So, in 1967 and ‘68, Dr. King and SELC launched the Poor People’s Campaign, which took him to Memphis and supported the striking sanitation workers. Can you talk about the message and the meaning of what was then his last speech entitled, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” and the days leading up to his assassination on April 4, 1968.

[00:25:15] Jonathan: Yeah. So, as I said, he felt like people weren’t listening to him anymore and that people didn’t want to talk about segregation and, discrimination in the North. And they didn’t want to hear what he had to say about the Vietnam War. And instead of, you know, giving up or deciding he was going to take some time off. He decided he was going to go all in. He was going to prepare his biggest protest of all, and he called it the poor people’s campaign. He was going to bring thousands and thousands of people to Washington, D.C. And they were basically going to occupy Washington, shut down the government, if necessary, until we reckoned with the discrimination with the income inequality that was plaguing this country — and it wasn’t going that well.

[00:25:55] Jonathan: King was having trouble recruiting, but it scared our government, it scared the president, it scared the FBI. They saw this as a terrible threat, and they ramped up their efforts to try to disrupt and discredit King. You know, at the same time, he was asked to go to Memphis to support the striking sanitation workers and his friends, his allies all said, don’t go, it’s just a bunch of garbage workers that, you know, you’ve got bigger problems. You got this poor people’s campaign to prepare for, but King felt like he had to go, that these were exactly the people that he cared about, these are the people he was trying to help. And that’s why he wanted to make a poor people’s campaign because these sanitation workers were working for low wages in unsafe conditions and he had to call it out.

[00:26:39] Jonathan: So, he was in Memphis and maybe didn’t have to be there. And that’s of course where he was assassinated. And as you mentioned, he gave one speech the night before he was killed. And people feel like maybe he forsesaw his own assassination, because he said that in that speech, like anyone else, I’d like to live a long life, but I know that that might not be for me. And it doesn’t matter now, because all that matters is that I do what I believe, that I fight for what’s right, and that I do what God put me on Earth here to do. And, he said, I may not reach the promised land, but I have seen the promised land, and I know that together as a people, we will get there.

[00:27:16] Alisha: Just a remarkable human being with such a tremendous burden that he carried. My last question for you before I ask you to read an excerpt from your book given the current state of national affairs, how should public officials, parents, schools alike draw on lessons and teachings from Dr. King’s life to better understand race. And provide higher quality, spiritual and political leadership to America?

[00:27:44] Jonathan: Wow. That’s a big question. You know, I think it’s great that we have a national holiday for King now, and it’s great that we have a monument for him. Monuments are easy to overlook and national holidays. It’s easy to stick with the simplified, safe version of King that we want to teach. It’s easy to talk about a dream and judging people by the content of their character. We need to remind people that King was a radical and that we can handle the truth of what he was trying to tell us. We don’t need to water it down. He was trying to tell us that if we didn’t address income inequality, if we didn’t address the roots of racism, if we didn’t atone for the sin of slavery, that we were going to continue to have the same problems over and over again.

[00:28:32] Jonathan: We were going to continue to find ourselves in conflict with one another. We would continue to treat people as other and as inferior and that we can do better if we just face the facts and deal with the truth. So I think that, you know, we should teach kids about it, “I Have a Dream,” but we should teach them about the first half of that speech too. We should make sure we teach them about the Letter from a Birmingham Jail. We should teach them that our own government, which celebrates him now with a national holiday, set out to destroy him.

[00:29:00] Alisha: Thank you for that. Wow. Would you read for us an excerpt from your book, so that our listeners can hear a part of your writing?

[00:29:11] Jonathan: All right, I’m going to read the very end because this is what I was just talking about. That we now have — just to set it up here — we have a thousand streets named after King, we have hundreds of schools we have watered down his message, and here’s what I say at the end of this epilogue: “Our simplified celebration of King comes at a cost. It saps the strength of his philosophical and intellectual contributions. It undercuts his power to inspire change. Even after Americans elected a black man as president, and after that president, Barack Obama, placed a bust of King in the Oval Office, the nation remains wracked with racism, ethnonationalism, cultural division, residential and educational segregation, economic inequality, violence, and a fading sense of hope that government, or anyone, will ever fix these problems. Where do we go from here? In spite of the way America treated him, King still had faith when he asked that question. Today, his words might help us make our way through these troubled times. But only if we actually read them, only if we embrace the complicated King, the flawed King, the human King, the radical King. Only if we see and hear him clearly again, as America saw and heard him once before. Our very survival, he wrote, depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant, and to face the challenge of change. Amen.”

[00:30:40] Alisha: Wooh! Jonathan, thank you for this powerful, remarkable, exceptional, maybe even call to action to all of us as we celebrate the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Thank you so much for being with us.

Albert: Thank you, Jonathan.

[00:30:57] Jonathan: Thanks for all the great questions. I enjoyed talking to you.

[00:31:17] Albert: Great interview. Great interview indeed. Absolutely learned a lot. Well, before we close out first, we have the Tweet of the Week, which comes from our friends at Education Next from this year’s top 20 EdNext articles of 2023. Supreme Court opens a path to religious charter schools, but the trail ahead holds twists and turns. And this was an article written last year by Professor Nicole Garnett. Check it out if you missed it last year, it’s a fascinating article. I mean, she’s a legal expert on education law and it’s an article about the possibility of religious charter schools. So, check that one out, but also check out the rest of the top 20 articles from Education Next from 2023. It gives us a nice, brief digest of what happened last year. Alisha, thanks for being with me on the show again. Great to co-host with you as always.

[00:32:10] Alisha: Absolutely. Thanks for having me. This was great today.

[00:32:13] Albert: All right. And that brings us to the end of this week’s episode. Join us next week as we talk to Cara Candal, who is the vice president of policy for ExcelinEd. And she’s going to join us as we kick off National School Choice Week for 2024. So, join us next week as we sit down and chat with her with all things school choice. But until then, I hope you have a great day, and I’ll see you next week.

[00:32:39] Alisha: Happy King Day!

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Prof. Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas and Alisha Searcy interview New York Times best-selling biographer of MLK, Jonathan Eig. Mr. Eig delves into MLK’s early spiritual leadership, the influence of Langston Hughes on his speeches, his relationship with his wife, Coretta Scott King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s challenges. He explores historic events in Birmingham, Alabama, the March on Washington, MLK’s struggles in Chicago, the Poor People’s Campaign, and the events leading to MLK’s assassination in 1968. Eig underscores the multifaceted aspects of MLK’s life and provides insights on drawing lessons for contemporary challenges in race relations and leadership. Mr. Eig closes the interview with a reading from his book, King: A Life.

Stories of the Week: Albert reflects on a story from Education Next a memoriam for former Pioneer Institute and national charter school leader Linda Brown; Alisha reviews a story in The Salt Lake Tribune on how Utah has no plans to change it’s lowest-in-nation education spending.

Guest:

Jonathan Eig is the bestselling author of six books, including his most recent King: A Life, which was nominated for the National Book Award and The New York Times hailed it as the definitive biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Jonathan’s previous book, Ali: A Life, won a 2018 PEN America Literary Award, and Esquire magazine named it one of the 25 greatest biographies of all time. He also served as consulting producer for the PBS series Muhammad Ali, directed by Ken Burns. Jonathan’s first book, Luckiest Man:The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, reached No. 10 on the New York Times bestseller list and won the Casey Award. His books have been listed among the best of the year by The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, and translated into more than a dozen languages. Jonathan’s appeared on the Today Show, NPR’s Fresh Air, and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He studied journalism at Northwestern University, and went on to work as a reporter for The New Orleans Times-Picayune, The Dallas Morning News, Chicago Magazine, and The Wall Street Journal. He lives in Chicago.

Jonathan Eig is the bestselling author of six books, including his most recent King: A Life, which was nominated for the National Book Award and The New York Times hailed it as the definitive biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Jonathan’s previous book, Ali: A Life, won a 2018 PEN America Literary Award, and Esquire magazine named it one of the 25 greatest biographies of all time. He also served as consulting producer for the PBS series Muhammad Ali, directed by Ken Burns. Jonathan’s first book, Luckiest Man:The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, reached No. 10 on the New York Times bestseller list and won the Casey Award. His books have been listed among the best of the year by The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, and translated into more than a dozen languages. Jonathan’s appeared on the Today Show, NPR’s Fresh Air, and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He studied journalism at Northwestern University, and went on to work as a reporter for The New Orleans Times-Picayune, The Dallas Morning News, Chicago Magazine, and The Wall Street Journal. He lives in Chicago.

Tweet of the Week: