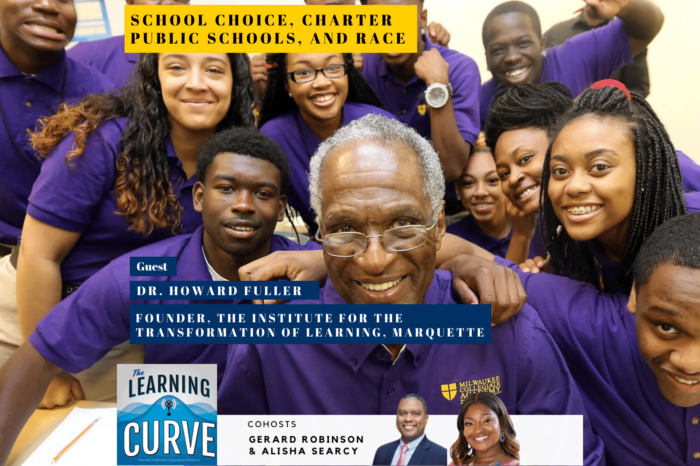

Marquette’s Dr. Howard Fuller on School Choice, Charter Schools, and Race

/in Featured, Podcast /by Editorial StaffThis week on The Learning Curve, Gerard and guest cohost Alisha Searcy speak with Dr. Howard Fuller, Founder/Director of the Institute for the Transformation of Learning (ITL) at Marquette University, about the state of education reform and the ongoing push to expand school choice and charter schools. Dr. Fuller discusses educational options available to minority students today, the role of charter schools in overall reform of urban education, and how the nation’s political, civic, and religious leaders can address racial divisions. He also shares with listeners highlights and frustrations from his long and remarkable career in education.

Stories of the Week: Alisha cited a New York Post editorial lamenting a further watering down of New York State high school graduation requirements. Gerard noted a U.S. News & World Report story about housing insecurity and how some school systems are seeking to help students who are homeless.

Guest

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a transcript here:

TheLearningCurve_HowardFuller

[00:00:00] Gerard Robinson: Hello, listeners, welcome back to another wonderful, exciting hour of The Learning Curve. This week I’m joined by not only a long-term friend and colleague, but someone I enjoy tag teaming with. Whenever I get an opportunity, it’s Alisha Searcy. Alicia, how are you doing?

[00:00:37] Alisha: I am wonderful, Gerard. How are you? It is fantastic to be with you.

[00:00:43] GR: I’m doing well. It’s beautiful, Charlottesville, Virginia, a little windy today. I’m assuming the weather in your neck of the woods is probably a little sunnier than my side.

[00:00:52] Alisha: It is, although we are still having three or four seasons in one day in the winter. Right now it appears to be spring about [00:01:00] 70 degrees and beautiful. So we’re grateful for that. This morning, I think it was 40 degrees.

[00:01:05] GR: Oh wow. Yes. Wow. Not a good thing. Well, speaking of good things and changes, what’s the story of the week that caught your attention?

[00:01:13] Alisha: So this one was very interesting. Uh, New York Post has an article by the editorial, or editorial, I should say, it’s entitled New York’s Education Leaders Take Another Step Against Excellence.

So, I’ll just preface this by saying I live in Georgia, you know, I know a lot about education in Georgia but I’ve also been a state legislator and a superintendent, and so I do follow. Some things nationally. And so this editorial is essentially following the fact that New York continues to lower its standards for students who are graduating from New York Public Schools.

And what’s interesting to me, you know, I always think about this, Gerard, from a policy standpoint, I’m, I’m a big picture strategic. [00:02:00] Thinker. And so while they make some great points about things like students will only have to get a 65% on these five exams that they’ll have to pass in order to graduate, obviously 65%, anywhere else, right?

If you get a 65 on a paper that’s failing, that’s a problem. And so this whole editorial is about the lowering of standards. And what does the diploma actually mean by the time students graduate? And I think that’s a very important point. I am deeply concerned about the lowering of standards period.

I think I might have even said last week, On this same podcast that in Georgia last year, they were all excited about the historic high of graduation rates across the state. But you kind of have to put an asterisk by that number, right? Because you had a number of students who didn’t return to school, right?

There’s lower enrollment. You know that a number of students didn’t get [00:03:00] everything they needed because of Covid, and so you have to wonder what does that graduation rate actually mean? And I think it’s similar when we talk about what’s happening in New York and probably plenty of states around the country.

I think the goal here, Is to make sure that students have mastered, the content that we want them to have. We want them to obviously be able to do math well and read and write and all of those things. I don’t think the goal is to lower the standards in a way that we don’t know. If they can be successful right outside of high school and whether they’re going to college or going into career.

So I think this editorial is important and raises some really good questions. I will say one thing though that I do agree with, and it may be a little controversial is that they’ve replaced some of the tests with students being able to do presentations. And I know that we’re stuck on. those standardized tests, but I for one, believe that there are other ways that we can measure [00:04:00] how students master the content.

And so I like this idea of students being able to do a presentation. I’m not saying across all content areas, but I do think there’s value in having alternative, if you will, or differentiated ways that we assess students and their mastery. What do you think?

[00:04:19] GR: Well, you hit all the right points. I mean, just think about New York City. It’s the largest school system in America. A million students predominantly students of color, urban high poverty, and they’ve also got public schools that are not charter schools that are doing well. And we know that some of the district in part is being carried in part by students who are in charter schools.

[00:04:40] GR: So New York has been a place where people have experimented with everything from standards based learning to a mayoral takeover. To community control back in the late sixties really in Oceanville. And now we’re to standards. So what I wonder is, are we calling this what it really is? Is it really lowering standards? Or are we lowering expectations? And I think it’s a difference with the distinction. I understand the importance that some students, in fact just aren’t great standardized test takers. Guess what? I’m gonna raise my hand right now. Yeah, I wasn’t a great standardized test taker in high school or even for graduate exams, so I own that and I know it well.

I’m with you. I believe we can find creative ways for students to demonstrate proficiency and places in Tennessee, California, Louisiana, your state, and some of the urban area. People have found ways at the local school site to come up and say, Hey, here’s what you can do. So I think we can do that, but I do think at some point it’s really a question of are we lowering expectations?

Have we reached a point where we basically have said in an impolite way, the students that we have today, Aren’t up to snuff and we simply can’t educate ’em. That’s one role that’s putting it on students. The second role is our [00:06:00] teachers are burnt out, they’re tired, they’re overworked, underpaid, and we just can’t give them the kind of professional development and financial resources necessary to get them up.

That’s a human resource dynamic. Third, that families are engaged enough, or if they are engaged, it’s about, you know, one issue. It’s not enough. That’s a family piece. I think there’s some valid points in all three of them, but we remember one thing, education in many states. In a governor’s budget is the number one line item in New York City with a million students and a multi-billion dollar budget.

It’s not as if you woke up yesterday and realized, wow, we’re working with high poverty kids who are from challenging ZIP codes. Some of them are doing well, some of them are not, and the best we can do is lower standards. No, I think what we’re doing is we’re lowering expectations. And we’re saying that we are simply going to find a new way to calculate it. Now think about it, A 65 is now a pass rate. I don’t believe— and so for people who are in the military, I wasn’t in the military. My brother was, my father-in-law was in the military. I know from reading research from people who are going into the military that they said A number of students today, black, white, Hispanic, aren’t passing the ASVAB.

And that’s the test you need to get into the military. I don’t know if the cutoff score is 80. I don’t know if it’s 65. I’d be shocked if someone said, if you get a 65, you can join the military. We know that if you are taking a driver’s test, getting a 65 isn’t gonna get your driver’s license in Virginia or California.

No. I do realize in New York or Georgia, I do realize a lot of people don’t have a driver’s license. They’ve never driven a car. I worked in New York and was shocked to meet people who had never driven, but they also have a great transportation system. But would we, let’s use state of Georgia, but also New York.

Would we bring on a football player to our high school football team or college team if he ran or he, if his overall [00:08:00] score for athletic prowess was 65 or under? No, we’re, so we’re saying we’re not concerned about whether you can get a 4.0. We just want you to run a 4.3. In the four 40 or in the, the 40 yard dash.

I think this is a bigger issue, and I’ll put it in context of the fact that this is the same month, 40 years ago, where a nation at risk report was released to the American public. And we just had a great conversation about that at Aspen. And one of the things they said is that if a dangerous foreign enemy put up on us in 1983 an education system that produced the kind of results that we have.

Someone would say this was an active war. I don’t think it’s hyperbole, cuz I understand the context of why they were using military vernacular at that time, given the fact that 80% of the people who were in the US Senate military experience and 50% of the people in the house had military experience.

We were also in the Cold War, the Berlin Wall had not fallen, so that kind of stuff [00:09:00] was real. You fast forward to today, and you’re saying 65% is a passage rate where we know that right now, 75% of the school age, I should say, military age, men and women who should qualify for the military no longer qualify for the military because of education, because of criminal justice.

And because of health. And so I believe that there’s a bigger conversation standards. Yeah. But I think we’re just being impolite. Mm-hmm. Uh, Or politely saying this is really lowering expectations. It is.

[00:09:32] Alisha: First of all, that’s one of the reasons why I love talking to you and learning from you are walking encyclopedia, which I know kids today have no idea what that is.

But thank you for all of that knowledge. And I think you’re exactly right. And that’s why I say, you know, this is a bigger question, right? It’s not just, what tests are you gonna pass to graduate from high school? But this is about what do we want students to know in this country? What does it mean to have a high school diploma? What does it mean to be prepared for the world? And I worry that we get. Caught, in these conversations about a 65 versus an 80 or whatever it is, and not having the conversation about what are our expectations for our students. I couldn’t agree with you more. And it, it worried me. It worries me.

Actually, you know, I, and you and I both have school-aged children. I now have three. And so as I watch what’s happening in schools, and I, again, you bring up a great point about the status of teachers and the burnout and compensation, mental health mm-hmm. The number of issues mm-hmm. That educators are facing.

What kind of system do we have now, and frankly, where are the ideas that will help us to reform, if you will. This education system, which is why I’m so excited about who we’re gonna be talking to in a little bit.

[00:10:55]

GR: Exactly. And I then I’ll think about it, when you mentioned the 65 all [00:11:00] percent and our teachers just think of the number of teachers who say they’re not coming back next year.

Yeah. Or those who didn’t come back. This fall, they’re done. And when we can’t get teachers into the classroom, and at the end of the day as many policies and, and research papers that I can support or write, when the teacher closes the door, he or she, that’s their room and that’s the work they’re doing.

So we’ve got some big issues ahead. Yes. And in fact, it kind of leads into my story of the week, which is from USA Today how schools serve homeless students. It’s by Kate Ricks. Growing up, as long as I can think about it. I don’t remember homelessness being a dynamic in my school. I’m not saying that we had children who weren’t homeless, I just didn’t know.

Today we know a whole lot more about homeless children and, and we definitely had them in the seventies. So this article really talks about what public schools are doing smartly and [00:12:00] through partnerships. To help out the families. So let’s just look at 2020. According to one statistic, there were more than 50,000 families with children who experienced homelessness over the previous year.

And this actually meant that we had over 1 million school-aged children who identified as homeless. And this information’s coming from the National Center for Homeless Education. And it’s an organization in a previous life where I’ve had an opportunity to go to their website to read their information.

And it really is a good one-stop shop from national perspective on homelessness, but you can also dig down deeper. So that would be one spot you should go to. When we think about the homeless population, the first person that comes to mind is a single adult, often a single man and not children, but we know the face of homelessness, in fact includes the women with children.

But when you think about how you define it, you know, I’ve got my own definition, but according to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development they define homelessness as people living in shelters or places not meant for human habitation. I said, wait a minute, not meant for human habitation.

Their families right now who live in homes that have been dilapidated or have been challenged through a whole, for a whole lot of reasons, particularly in in the South, during hurricane season have never recovered. They live there. Now, you wouldn’t call those people homeless. You would say they live in a bad home.

But to think the definition is that I find it interesting. I didn’t know. So that’s it. But the author also says, well, that’s, he’s actually agreeing, saying, well, I’m not sure that’s the case because there are many families who are doubling up. Living with other families. Mm-hmm. Right now, because they don’t have a home, or they are, as one of my niece will say, cal surfing.

And so homelessness is much broader than we, than we define. But what are schools trying to do? So there’s one school our district, I should say, in [00:14:00] Vancouver, Washington who said, well, we’re not gonna just talk about it. We are going to do something. And so in Vancouver, they’ve actually partnered with a local housing agency.

To deal with the homeless crisis. This crisis, in fact, started with them in 2014 when 150 residents at a village apartment were suddenly evicted. And the school system, social service leaders and others realized, wow, we have no plan of accident. So, Over a hundred families, nearly 90 children had reached out for help.

People had come together, leaders and organizers. They helped 75 families find new homes. But it was through that experience where they said, we’ve gotta do a better job of working together between school and agency. And so the Clark County, which is where there are today they created liaisons with the homeless agency so that the agency can work directly with families to try to provide support. I do know that a lot of principals have identified homeless children, and there’s a dynamic that a. You don’t want your other, your classmates to know, you may not want your teacher to know. Mm-hmm. And so one of the reasons you work with an agency is the agency can actually be a go between, between family schools and students, so as to keep some of this private, but also to provide services.

We also have an example from Minneapolis. they have the homeless and highly mobile service for Minneapolis public schools. Minneapolis for many came more to national light because of the killing of George Floyd. When people think about Minneapolis, they know that it’s rank as one of the smartest cities in the country.

Based upon people age 25 and older who have a bachelor’s degree. But people often forget there’s a lot of poverty in that city. Mm-hmm. Also a lot of homelessness. And so through their partnership, the school is working with the homeless agency using mobile technology to help families. And since I’m talking about homelessness, let me give a shout out to my colleague, Tony, who is one of the co-founders of the high school for the recording Arts. His charter school is over 25 years old, one of the oldest in the country, but he started that school in part to help children in in Minneapolis and St. Paul who said, you know what, I may not go to college, but I wanna get involved in the music career.

And this is the home of Jenny Jam Prince and others. But what he often mentions in speeches is that nearly 40% of his student body. For the early years were homeless. Mm. And I had a chance to visit his school last year with a colleague of mine from the University of Virginia, and they identified that the average student going to their school was outta school for two years.

Two years before they arrived at his school. And so he’s someone living this. And 25 plus years in the game, he’s changed the trajectory from moving Soons from poverty to possibility and families and teachers. In fact, one of the former students is now a guidance counselor at the school. So just wanna give him a shout out to Tony as well.

And then lastly, let me give a shout out to Boston. And, you know, Pioneer, that’s their home, well and Boston, the school system is also working with the local homeless shelter to do the same thing. It is a subject I will not say that I know as much about as I should. This was a good eye-opener.

[00:17:13] GR: I know it exists, but it’s good to see our public school systems being the kind of partners. You and I know they are, but this is good opportunity to give them a shout out as well.

[00:17:23]

Alisha: It is. And I can tell you, Gerard, when I was superintendent, you know, there are many experiences that I had, but one of the ones that I will never forget we had two young ladies in our elementary school who were homeless.

They lived in their mother’s car. And I don’t believe that their classmates knew, but they would come in every morning, take baths in the bathroom at the school, put on their uniforms and go to class. And I would, watch them walk by, you know, in their lines or in their classrooms. I don’t think you knew just from the naked eye what was [00:18:00] happening.

But I often think about them, just the level of. Persistence and grit. And endurance that it takes for children to show up to school every day knowing that they may or may not have had a meal the night before. They may be getting their meals at school. They don’t have, all of the, basic things that many of us kind of take for granted but still show up to learn every day.

And I know that federally, you know, schools are required to provide some services through the McKinney-Vento Act. But if I recall correctly there were never enough resources for these families, to help with food, to help with shelter, to help with some of the other basic needs, like school supplies.

And so then you think about what does it mean for a teacher and for the school? To have the resources, I think the article mentions this, you know, having extra supplies, extra snacks mm-hmm. To make [00:19:00] sure that these babies have what they need. So my heart just aches for families who are dealing with significant, you know, life and death issues who are still showing up to school every day to learn and to get what they need. And I, know that obviously more resources are needed at the school levels so that we can address these issues and we can help support, and as you said, you know, kudos to the school systems and the schools that have figured out how to partner with. the food banks in their communities, or homeless shelters or any of these services that they can partner with to make sure the kids have what they need and families have what they need.

One of the schools in Fulton County here in Georgia does a really good job of having both a clothing and a food pantry so that, parents who may not have jobs or may need clothing to go to an interview, have a place that they can go in the school to get those resources. Same thing for food.

And some would say, well, [00:20:00] you know, is that the role of the school? That has become more and more of the role of the school where we’re asking them to do a lot more with a lot less. Because this is where children are spending most of their time. This is where we know we have these resources and they need it.

So I too am glad that this article came out so that we could all be more educated, about what’s happening with children and families in our country. And I think it also speaks to more work that we have to do at the school district, state, federal level to make sure these families have the resources they need to be successful.

[00:20:33]

GR: All great points and thanks for sharing the story about Two students you knew who lived that lifestyle, because I’m sure if we’ve contacted five of our friends who are principals or teachers, they know someone. Absolutely. And it’s, and it’s also just worth noting that a lot of the face of homelessness, when we think about it as people who are there for six, seven years, a lot of women who are coming out of abusive relationships or going through divorces who have children often will find themselves [00:21:00] in shelters.

Not because they’re lazy, not because they’re uneducated. Not because they can’t work, it’s because they had to leave a very violent situation Yes. At that moment and had to transition. And they may find themselves in that situation for a month, maybe a year. That’s an aspect of homelessness that we don’t think about.

And I also think about in our era of hyper-partisanship that folks on my political side of the fence, the Republicans, that sometimes we overlook that there are aspects of poverty that are generational aspects of. Homelessness that are generational, but let’s also, every now and then take a look at the laws we voted for that may have played a role in making that possible.

So just my 2 cents.

[00:21:43]

Alisha: Yes, agreed. And thank you for lifting that up. It’s so very true, and it’s a cycle, you know, once you are in the cycle of poverty, it’s so hard to get out because of just as you said, the policies in place, the systems that we put in place. I think about the title loan programs and all of these [00:22:00] things that are out there that keep you in that cycle. And we forget about that sometimes.

[00:22:05]

GR: Well, someone who knows a, great deal about poverty and how to use education to bring people out of it uh, will be our next guest Dr. Howard Fuller, who’s going to join us.

[00:22:43]

Alisha: Gerard, I am excited to be with you today because we have one of my favorite people on the entire planet, Dr. Howard Fuller here with us today. Dr. Fuller is the distinguished Professor, emeritus of Education and Founder, director of the Institute for the Transformation of Learning [00:23:00] at Marquette University.

Dr. Fuller has many years in both public service positions and the field of education, including superintendent of the Milwaukee Public Schools. And director of the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services as director of the I T L, Dr. Fuller supports education options that transform learning for children while empowering families, particularly those of low income.

To choose the best school options, Dr. Fuller holds a BS degree from Carroll College and m MSA degree from Western Reserve University, and a PhD from Marquette University. Welcome Dr. Fuller.

[00:23:36]

Howard Fuller: Uh, Alisha, thanks so much. It’s very great to hear your voice.

[00:23:40] Alisha: Yours too. And thanks for all that you do have done and continue to do. So I wanna jump in. Over a decade ago, race to the Top made a big national push on charter schools, testing standards, and teacher evaluations. While COVID has seen public schooling flooded with billions of dollars in additional federal funding, the 2022 NA Results and General Momentum of K-12 education reforms seem to have stagnated in recent years. So what’s your take on the current overall state of K-12 education reform in the United States?

[00:24:17] Howard Fuller: my take is some kids matter more than other kids. And the reason I want to start there is because these test scores that you’re talking about, you can go back over the last 30 or 40 years and you’ll see periods where.

They seem to be getting better for poor kids, children of color. Then they stagnate. Then there’s this, there’s that, whether it was covid or something else. There’s always something that happens so that you don’t see the kind of achievement levels you would want to see for all children in this country.

And so what I’ve concluded, And, and I [00:25:00] could be wrong cuz I’ve been wrong about a lot of stuff. But I’ve concluded that the reason why this continues to happen is that poor children, particularly poor children of color, but I think this is probably true for poor children generally, irrespective of race, they don’t matter as much as kids who have money.

And the reason why I’m saying this and it relates to NAC scores or other scores that you can use every year. I shouldn’t say every year, every couple of years. There’s an article in the Milwaukee Journal sent that says there’s a crisis in reading for black children. this crisis has been with us for at least 30 years. And so the way I look at this is if we can all agree, and maybe we can’t, but let’s assume we can all agree that black children are not genetically incapable of learning how to read. Let’s say that it isn’t their genes if it isn’t their gene. and we actually know how to teach kids reading.

It isn’t like there’s no knowledge base out here about how to teach kids reading. Then the question is, how do these scores continue to be this way? And so what I’ve concluded is it continues to be that way because for the political structure wri large, these children that we’re talking about, Are not important because if they were important, we would have a plan.

We would have the money, and we would have the, implementation strategy to change this. and it doesn’t change, and so I’m left saying it doesn’t change because we don’t have the political will to insist that it changes.

[00:26:52]

Alisha: And that is so hard to try to accept, right? Hard to hear, hard to accept, but you certainly can understand given the numbers. And I would argue that just looking at Naip alone it’s not poor. It’s not. Students of color, it’s all of our kids, right, are not reading at grade level. They’re not, proficient in math. So it’s, we are certainly in a crisis. But I would, agree, I don’t, there doesn’t seem to be a real plan.

And I think one of the things that we thought and I’ve only been in this movement, you know, maybe 15 years. You’ve been in it longer than I, we thought that choice would be one of those things that would allow students who were in schools that weren’t working for them to have options elsewhere.

And so when we think about for example, the landmark, US Supreme Court decision, Espinoza versus Montana Department of Revenue and Carson v Makin, it’s torn big legal holes and the anti-aid Blaine Amendments that blocked wider access to private and religious schooling in nearly 40 states. And since 2020, we’ve had a huge expansion of voucher education, tax credit, and ESAs in over 20 states across the country. Can you share your views on the long battle and progress of School choice in America?

[00:28:10]

Howard Fuller: Listen you said so much. I mean, I do wanna go back and just. Reference a point that you made that all children in the United States in comparison to? It depends upon what comparison you want to make to develop countries in the world that in many respects, our test scores.

I have not looked at ’em in the last few years, but the last one I looked at on our test scores were lagging behind other developed countries in the world. Yes, but still, When you look at it, you still see this enormous gap between white children and children of color. So although think you could rightfully argue that no kids are doing as well as they, they should, we still got to [00:29:00] acknowledge that there’s this enormous gap between black kids and white kids or black kids and Latinos and so forth, and that presents.

A special problem in and of itself. Agreed. So I think I’m accurate on that, but I know Gerard knows everything and he’ll know whether or not I know that’s true. but having said that, to talk about the, issue of parent choice, first of all, as you know, I’ve always supported parent choice and not school choice and that to me was more than just. A semantical difference because my goal was to try to make sure that low income and working class families had some of the options for their children’s education that those of us with money have. from my standpoint, I’m concerned that some of the expansion of parent choice in this country right now is an expansion where low income and working class families will not [00:30:00] be more advantage than those with money because I, got in this battle.

So, so that those of us who already got money would give more money. my view was how do we provide some of these options for low income and working class parents that those of us with money already have? Now, having said that, the point that you made is something that we gotta ask ourselves, because I did think that at this point in time, if we could implement parent choice, that we would see a radical difference.

In the achievement levels of kids because we would create more great schools and et cetera. When you look at Milwaukee, and Milwaukee is a good place to look. One of the, interesting things that we’re not interesting, difficult things that we’re facing is that we set up a, a parent choice policy atmosphere.

But what we didn’t [00:31:00] do was deal with. Equal funding. and it isn’t even just equal funding because equal funding won’t do the job. We have to have equitable funding and that’s very, very different. But in Milwaukee, for example, we don’t even have equal funding when it comes to per pupil allotment for the kids. So if you were family of three, a low income family of three in Milwaukee, And you sent one of your children to mps, Milwaukee Public schools, you would generate like 14,500 some dollars. Somewhere in that arena. If you sent ’em to our school, which is an independent charter school, you would generate 9,800.

If you send ’em to a private school and it was an elementary school, you’d generate 86. If it was a high school, you, you generate 89 or. Or, or something more. So now what we’re doing is we’re in a battle to try to close the gap [00:32:00] in funding because the reality of it is like at our school for example, we get kids who come into us.

In the ninth grade, 70% of them come reading two, three grade levels behind, and it, is an enormous challenge to move those kids. And we’re being asked to do that with far less resources now. let me put a pin on that and get to your, what I think is the central point, and I’m hoping I’m, I’m at least approaching, trying to address it.

I think the reality of it is that we are not going be able to create really great schools in a critical mass in a society that’s not great. In other words, schools are an integral part. Of the institutional fabric of American society, those institutional fabrics are interrelated. When you’re talking about family, you’re talking about [00:33:00] government, you’re talking about the economic structure.

You know, you talk about these five or six. Main institutional frames for how a society works well, they don’t work independent of each other. There’s an inner relationship between those things. So we’re not gonna be able to say, we’re gonna really create great schools. but the kids are gonna come to these schools, they won’t have healthcare.

They won’t have adequate housing. We’re gonna try to make sure that the, parents of these children are cut off from political power by putting as many barriers as we can in terms of their being able to vote. In other words, what I’m saying to you is, is although I think that schools can make a difference, we’re gonna have to face the stark reality that if we’re not gonna make significant changes in the totality.

Poor children’s existence, we’re not likely [00:34:00] gonna see great, great movement in schools, but we can make a larger difference in schools than what we are making if we put the resources and a plan towards actually making that happen.

[00:34:14]

Alisha: Understood. Regardless of the type of school their parents choose.

[00:34:18]

Howard Fuller: You talk about the way that people get to a school. And then you talk about, okay, what happens in the school? so you can create mechanisms to get people to a school, but then you gotta say, okay, but. Is this a great school? And then the question becomes, what are the characteristics of a great school? Right? And then what I’m saying is once you even get to that and you’re clear about some of the characteristics, and you can implement ’em.

Cause you see these schools that do extraordinary work with the children that we’re talking about. but it takes extraordinary effort. Yes, it does. In, in order to even make. Small changes to say nothing about significant changes [00:35:00] without cheating and without adding yeast onto the test scores.

So what I’m saying is that we’re all, at least I’ll speak for myself, coming to grips with, I’m not gonna say naivete, but some of the, lack of recognition. On my part about all of the things that impact education reform when you’re dealing with the children that we’re talking about.

[00:35:23]

Alisha: Yeah, totally understood. I wanna go back to a point that you made earlier. It’s not lost on me and I think it’s important to given example, even in Atlanta where I live in the metro area, but in the Atlanta school system, there was a study done. Just a year or two ago that talked about the growth of black students and how long it would take them to catch up to white students in Atlanta, and the number is astounding. It would take 127 years for black students in Atlanta public schools to catch up with white students if there was no growth among white students at all. It’s staggering and unbelievable. But it speaks to exactly what you’re saying.

[00:36:09]

Howard Fuller: Yeah. And, I wanna go back to something you said earlier about how hard it is to accept this this being the kind of data that, you and I are, talking about right here. You know, I’m still talking to younger people who, well, everybody’s younger than me, but I’m still talking to people who are, engaged in struggle, in some form. Like I was talking to Ethan Ashley just yesterday, you know, because I’ve been. Pushing as you and Gerard know that you, I feel all of y’all owe me at least 25 years, and some of y’all are getting close now.

[00:36:39]

Alisha: I’m about 20. I I still got a long time to go.

[00:36:42]

Howard Fuller: Yeah, you’re saying I got a few more years to give you, but I think Ard and I might have been talking about this, but Derek Bell wrote this book Faces at the Bottom of the Well, he was trying to make the case that racism is like a permanent reality in American society. And so the, obvious [00:37:00] question would be, and it’s sort of similar to what you’re saying, that we look at this data and you start saying, well, it’s gonna take 127 years. You really begin to ask the question, well, is victory even possible?

And I’m a pessimist because what I, what I believe would be victory. I don’t see how that becomes possible, in the world in which we live. However, like what Derek Bell said in facing the bottom of the well is that you have to engage and struggle even if you don’t see the possibility of victory, because not the struggle is to co-sign on the injustice and I look at that every day and say, no matter how difficult it is, no matter how impossible it is, I owe it.

To the people who come before us. I owe it to the people who are with us now. I owe it to the people who are yet to come. To continue to fight, right? Yes. And to continue to say this is not acceptable. That No, no. Even though I don’t [00:38:00] see the movement, I’m gonna keep fighting every day because if I stop, Then I’m, telling you that this is Okay.

[00:38:06]

Alisha: Amen to that. Could not have said that better. And speaking of people who’ve come before us a century ago, two great black educators, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois started a national debate about vocational, technical and liberal arts education that’s still with us today. And so what’s your view on the historic vocational tech versus liberal arts debate as the best way to educate young people. And what do you think can be done to improve these educational options today?

[00:38:38]

Howard Fuller: Yeah, in some ways I, I mean, I think that’s a, it’s not a mischaracterization of the debate because to a certain extent it was, but it was a much larger debate actually. It was a debate over at that moment in history, should we be focused on quote n Arts to prepare people to be, citizens versus. Should [00:39:00] we be engaged in just preparing people to work? But we gotta remember, even though people say that was a vocational technical argument, it wasn’t that it was more, are we gonna continue to work in menial POS positions within the context of American society?

So what I would say is that the debate, as it sometimes gets characterized as a false debate. And so what I believe is that we need to prepare children and young people so that they can engage, as Paul Fri said, in the practice of freedom. Their ability to engage in the practice of freedom means getting to a point where they, can achieve some level of economic independence and I’m using that in quotes. And so from my view, the, like at our school right now, we’re, you know, this is something that we’re, dealing with. Even though our goal is to prepare kids to go to college. In the last 11 years, 100% of our kids have been accepted in college.

And on Friday they’re gonna tell us where they’re gonna go. Outstanding. It really is about preparing young people so that they can be economically, and socially productive. And so for some of our kids, it means going to college for some of our kids, it means going into a trade for some of our kids.

it’ll be starting a business. Like one of the things I tried to talk about when our superintendent is that. I don’t want all of our children to come out saying, who’s gonna gimme a job? I want some of them to have an entrepreneurial spirit. So I think the shortcut of what I’m trying to say is, I think we need to do both I don’t think we need to make this this huge.

Dichotomy. but a lot of times though, as you know, Alicia, when people are saying, well, we wanna train these kids to be in, vocational areas, they’re not talking about vocational areas where kids are gonna be able to earn a living wage. You know, it’s like, you know, when I went to [00:41:00] Germany to look at the School of Work effort, then, and as you all know, in, in Germany, they put kids into tracks. And what they used to at least, and once you got into the, college track, that was, that if you got into the vocational track, that was that, and there was no like cross-fertilization between those, two areas. But the vocational stuff that they were talking about wasn’t just low level menial jobs.

It was high level. Vocational and technical efforts. and as you all know, if that’s what we’re talking about, then kids have got to have a high level of math and science skills. This, this isn’t just about preparing kids to take the lowest level jobs in a society, and that to me is, where I think the, debate may have been or, some of the differences between Dubois and Booker T. and I say that because as you all know, Du Bois lived to be 90 something years old, and by the time he, died a, he had accepted a lot of the premises of both Booker T. and Marcus Garvey. Because, when you read what Du Bois said, because he wrote over such a long period of time, you could see the evolution in some of his ideas and some of the positions that he took, you know, later on in his life.

[00:42:16]

GR: To piggyback off that, right now there’s a debate going on about charter schools and whether or not they should exist and whether or not they should be a part of the public school system. Many people may not know that. Not only were you one of the founding of the national Alliance of Public Charter Schools, you were also his first chair and you’ve had a chance to see. See this grow from a national level. You also have your own charter school, but you’ve also seen the role of philanthropy the role, the money that Gates and Walton put into Milwaukee to build small high schools. There was a point where there was bipartisan support and right now it seems to be pretty thin. In your view, what’s the current state of the charter movement politically, and[00:43:00] can we get back to glory years, or are those glory days

[00:43:03]

Howard Fuller: gone? Yeah. You know, that’s a very good question, Gerard, and I don’t know that I can answer it, man, because I don’t have the national perspective that I used to have before I retired. But if you look at what’s happening in Wisconsin, it is really interesting because we have a Democratic governor and a republican legislature. And we have a state where Trump won by 20,000 and Biden won by 20,000. Right. That’s the reality of our state right now. We have put together a very broad coalition, the broadest coalition that I’ve worked in in a long time to try to impact this funding equality issue.

And we have a Democratic governor who is saying, And I met with him and talked to him. In fact, I like, we’re we’re friends and he’s saying, I’m willing to look at this issue of [00:44:00] closing the funding gap. You got a Republican led legislature that said, we’re willing to look at this issue of closing the funding gap. Now the question is, what is it gonna take? Well, one of the things that’s. Helping is that we have a 7.1 billion surplus, even though all of that money won’t be in play. But I, I think the fact that this is even possible in a state like Wisconsin said that there may still be the possibility of developing bipartisan.

Efforts on certain parts of this education battle, right? It doesn’t mean that there’s any possibility of us agreeing on everything. this is like critical race, all these other things that are floating out there, but for me it’s always about the search for where is it possible for us to do something that is bipartisan.

And again, the strength and the weakness of the charter school movement is just, it’s, it’s like a state by state thing, right? It’s the laws are different. The political possibilities are different. Like I said, I don’t have a good reading of how all of this is, working out nationally, but what I can say is that, at least at the moment, In Milwaukee or in Wisconsin, there’s the potential of doing something that people really thought might not have been possible.

[00:45:29]

GR: No, that’s actually good to hear because there are other states in a similar situation and maybe even reversed Republican governor, democratic legislature, Virginia, where I am as an example, where there’s not any coalition remotely as broad as yours of talking about trying to move charter schools to the next level.

So you did give us a great answer cuz we can look and see what your state’s doing to make a difference. Here’s the last question for you. So when George Floyd was murdered, there was of course a national reaction to it, [00:46:00] both to the streets as well as to corporate suites. People say, we’ve gotta diversified, we’ve gotta do this.

So we’re now in 2023, number of laws are being passed about race education. You’ve had a chance to see the ebbs and flow of race relations in the US that often follow the death of someone. King in the 68 people in the seventies and the eighties moving forward, what are your thoughts about the state of race relations now and how it is impacting education for the good or for the worst?

[00:46:34]

Howard Fuller: Well, first of all, man, I mean people, I, you know, when you get old and stuff, you are, and Alisha, one of the things you gotta try to do is try to temper your cynicism, which is hard. So when people was out here talking about postracial America and stuff, man, even with George Floyd and all of that cause, cause Gerard, you know, from spending time with me in Milwaukee, is that in 1985, I think it was, I always get to go 83. Ernest Lacey was killed with the policeman. IPO put his knee on Ernie Lacey’s neck in the same way as George Floyd was killed. So, when people were, were out here talking about, you know, look at how broad this is, and look at this white people marching and black people marching and all this, I was like, man, I hope y’all are right. But I don’t believe there’s ever gonna be in America anything that’s called postracial America. I don’t, I mean, I hope I’m wrong, and maybe I’ll be proven to be wrong, but I don’t see it. because from, the viewpoint that I operate on, we have a very, very polarized America, but it’s not un newly polarized America. It has been historically a polarized America. Now at different points in time, there are different movements that pop up, but there’s always a reaction to those movements. And so now here we set in 2023, going into 2024 with a very polarized. America a very polarized electorate, and race is still a central part of that polarization.

So what that says to me is what Derrick be says about the permanence of race. And that says to me, there’s gonna be ebb and flows. There’s gonna be periods of, oh, you know, this is getting better and periods of this is getting worse. But until something much more fundamental than I can envision. I don’t see Alicia and Gerard how we’re not gonna be fighting these, battles around race and they’re gonna come in different forms, you know, in different historical [00:49:00] periods. struggles that people face. They show themselves in different ways. The fundamentals are the same, but the manifestations of it are different, or the particular battles are different. Gerard, you know, history better than me and you know that you could make a comparison, at least I think you could.

I don’t, we haven’t talked about this. Between the period when Andrew Johnson took over. Right after Lincoln was assassinated, the period that we just went through with Trump and that, in my view, we’re still in, there are clear comparisons between the role that race was playing in the national debate and the national discussion in some of the same ways as it is occurring now and has been occurring over the last several years.

So again, I, you know, within my answer saying, I’m not a person who sees how the [00:50:00] racial discussion is gonna be better in this country. That’s not to say that it’s gonna be the same. That’s not to say that there aren’t periods where it seems like we’ve turned the corner, but then when you turn the corner, what you see is another corner. And that’s sort of how I view how this is gonna go. But I hope I’m totally wrong.

[00:50:21]

GR: Got it. Well, Dr. Fuller, Alisha and I thank you for joining us today for sharing your ideas and your wisdom. You always leave a good plate of food for us to, to dine on and some questions to take away. Yes. Keep up the good work.And for those of you who are listening, Dr. Fuller’s school is named after him. You can find it online, and they’re actually in the middle of a fundraising drive. So if you want to donate to the Dr. Howard Fuller Collegiate Academy uh, in Milwaukee, please go to that webpage to do so. Dr. Fuller, good hearing your voice, and we look forward to connecting with you at another point.

[00:50:58]

Howard Fuller: Yeah, thanks. Thank you so much.

[00:51:28]

GR: My tweet of the week is from Real Clear Education. May 1st. And it says, how to teach kids who flip between books and screen. I am still a reader of hard books. I also like to read books on screen. So I can be, I guess, ambidextrous that way. But many of our students can’t, won’t or believe they shouldn’t. So, this is definitely a tweet worth looking into. next week’s speaker is a first timer for us. Is Dr. [00:52:00] Mariella Martinez Cola. She is a assistant professor of sociology at Morehouse College in Atlanta. Your area in p. I know you were a a, Spelman alum. Yes. And the author of a book, the Bricks Before Brown, the Chinese American, Native American, and Mexican American Struggle for Educational Equality. It’s a subject that I don’t know a great deal about, and I learned about her through a presentation she made at the University of Virginia. So look forward to having her. So, Alisha, again, thank you so much for the tag team. I look forward to. Joining you on the show again, or now that we can travel again, people who wanna have debates about education, you can bring us two together .And let us do what we do. But always good to have you here and I look forward to the day that I can call you superintendent Alisha Searcy.

[00:52:51]

Alisha: Amen to that Gerard, I appreciate that. I can’t wait either. Come on,

[00:52:57]

GR: Georgia. All right. Come on, Georgia. [00:53:00] Let’s do it. Okay. Talk to you again.