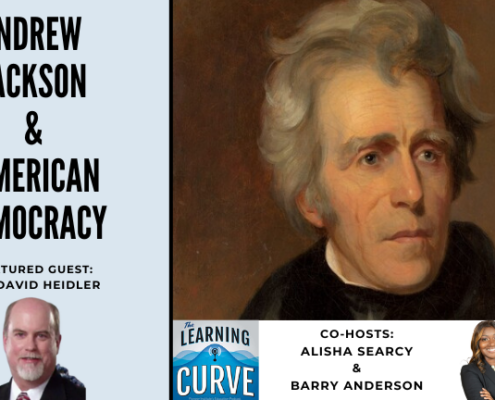

Lipan Apache Tribe’s Pastor Robert Soto on Native American Heritage Month & Religious Liberty

/in Blog: Education, Civil Rights Education, Civil Rights Podcasts, Featured, Podcast, School Choice, US History /by Editorial StaffThis week on “The Learning Curve,” co-hosts Gerard Robinson and Cara Candal talk with Pastor Robert Soto, a Lipan Apache religious leader and award-winning feather dancer who has successfully upheld his Native American cultural heritage and religious liberties in federal courts. As the country celebrates Native American Heritage Month, Pastor Soto shares his personal journey as a religious leader and describes the Lipan Apache Tribe. They discuss his experience upholding religious liberties under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, with the help of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, after being threatened with criminal fines and imprisonment for using eagle feathers in spiritual ceremonies (a practice banned by the federal government). He also offers thoughts on how American schoolchildren should be taught about the influence of Native American culture across the country and the proud history of Native peoples.

Stories of the Week: Education has played a key role in the Virginia gubernatorial election – is this campaign a harbinger of political battles to come? Analysis of data on the costs of a bacherlors degree, compared to students’ income two years after graduation, reveals a low return on investment at a number of colleges and universities.

Guest:

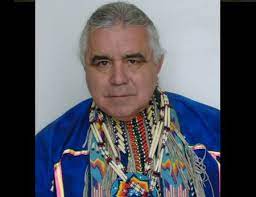

Pastor Robert Soto is an award-winning feather dancer and Lipan Apache religious leader who was threatened with criminal fines and imprisonment for using eagle feathers in his religious worship. He fought in court for over a decade to defend his rights to practice his faith in Christ as an American Indian under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Soto presently is the Vice Chairman of the Lipan Tribe of Texas, a tribe consisting of 4,500 members. He is the founder of Son Tree Native Path, which has performed and danced in 20 countries and 46 states. Soto is also the pastor of McAllen Grace Brethren Church and the Native American New Life Center in McAllen, Texas; My Rock Native Fellowship in Brownsville, Texas; and Chief of Chiefs Christian Church in San Antonio, Texas. In past years, Robert has had the privilege of working with the Seminoles of Florida and the Pueblos and Navajos of New Mexico along with 27 other tribal groups in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and South America. Pastor Soto holds a B.A. in Biblical Education from Florida Bible College, a Master of Divinity and a Master of Arts in Christian School Administration from Grace Theological Seminary in Winona Lake, Indiana, and a Doctor of Arts in Theology and Biblical Studies from South Texas School of Theology in Corpus Christi, Texas. He and his wife, Iris Soto, have been married for 46 years and have three children (one adopted), and eight grandchildren.

Pastor Robert Soto is an award-winning feather dancer and Lipan Apache religious leader who was threatened with criminal fines and imprisonment for using eagle feathers in his religious worship. He fought in court for over a decade to defend his rights to practice his faith in Christ as an American Indian under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Soto presently is the Vice Chairman of the Lipan Tribe of Texas, a tribe consisting of 4,500 members. He is the founder of Son Tree Native Path, which has performed and danced in 20 countries and 46 states. Soto is also the pastor of McAllen Grace Brethren Church and the Native American New Life Center in McAllen, Texas; My Rock Native Fellowship in Brownsville, Texas; and Chief of Chiefs Christian Church in San Antonio, Texas. In past years, Robert has had the privilege of working with the Seminoles of Florida and the Pueblos and Navajos of New Mexico along with 27 other tribal groups in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and South America. Pastor Soto holds a B.A. in Biblical Education from Florida Bible College, a Master of Divinity and a Master of Arts in Christian School Administration from Grace Theological Seminary in Winona Lake, Indiana, and a Doctor of Arts in Theology and Biblical Studies from South Texas School of Theology in Corpus Christi, Texas. He and his wife, Iris Soto, have been married for 46 years and have three children (one adopted), and eight grandchildren.

The next episode will air on Wednesday, November 10th with guest, Jennifer Laszlo Mizrahi, President of RespectAbility, a nonprofit organization advancing opportunities so people with disabilities can fully participate in all aspects of community.

Tweet of the Week:

Dismantling Denver: "The city was a national model for education reform. Then union-backed candidates took over the school board." https://t.co/ucg0pvRNQn

— Education Next (@EducationNext) November 1, 2021

News Links:

Will that college degree pay off? A look at some of the numbers https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/11/01/college-degree-value-major/

McAuliffe vs. Youngkin Is a Glimpse at Education Battles to Come https://reason.com/2021/11/01/mcauliffe-vs-youngkin-is-a-glimpse-at-education-battles-to-come/

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode:

Please excuse typos.

[00:00:00] Gerard Robinson [GR]: Hello listeners. This is Gerard Robinson. What a wonderful day to have you with us to talk about education on the learning curve. And this just isn’t any week, at least in Virginia, where I live, this is election week. In fact, by the time this. And you are listening. We will know who is the new governor of Virginia, or then again, because the polls say it’s so close, maybe we won’t, but either way, this is an important bellwether state for what education is all about.

[00:00:31] And my co-host Cara knows this all too well.

[00:00:35] Cara: I’m well, Gerard, I have to say, okay, I’m going to admit I had not been paying attention to Virginia until about a week ago. It was all like, Ooh, who’s going to be elected mayor of Boston and boy, equally Porter. I know it is an historic race here in Boston too, because no matter how it shakes out, we’re going to have our first female mayor ever, because, It’s such a progressive city.

[00:00:57] We are as Bostonians, really like to [00:01:00] think of themselves as progressive and those of us who didn’t grow up here, look askance and say, it really has it gone for you. But we’ll have our first female mayor , no matter how it shakes out. and it’s looking like our first female mayor of color as well.

[00:01:11] So, lot of cool stuff going on, but me and Virginia and talk about. Schools being right at the center of that battle. And. Boy. Oh boy, watch what you say about parents. Huh? Watch what you say, parents and schools and whether or not they should be making decisions. Because I think that parents on both sides of the aisle, no matter what, their politics, political persuasion, what they think about the current moment and the controversies of a critical race theory, et cetera, et cetera.

[00:01:39] Parents do want to have a say in what kids are learning in school both ways. Right. So I don’t know. Gerard, what are you reading and the tea leaves or what are you thinking about.

[00:01:48] GR: Well, one of the tea leaves we’re reading right now is from reason magazine. And in fact, it’s my article for this week.

[00:01:55] And it’s really about McCullough who is a democratic nominee, former governor and [00:02:00] Glen Yuncken the Republican nominee and the education is really shot to the top. At least the top three issues for Virginians as relates to who’s going to be the next governor. As many of, you know, I live in Virginia had a chance to work in state level leadership and every four years, in fact, we’re the only state with a one term governor by law.

[00:02:20] We’re going to have a new governor and what’s so interesting about this is the fact that a, usually how Virginia votes you’re going to see. An outcome in the white house. So for the most part, minus what happened when McCullough was an office that we had a Republican in the white house, then you found a shift either in the executive branch or in the legislature for the opposite color.

[00:02:41] So we’ll see if that makes a difference. This time, Virginia, for the last three presidential cycles is the only Southern state to have gone blue all the way through and Trump. Virginia, the last go round, but what’s so unique about this is there was a debate between both of the candidates and the course, the question of [00:03:00] parents and parent rights would come up and McAuliffe said he doesn’t believe that parents should have a say so of their kids’ education.

[00:03:06] And the Republican y’all can say something a little different. Now I listened to it and , I sparsed out what he said on one point what he was saying. Parents shouldn’t tells schools how to run schools, how to pick a curriculum. And if someone had to sit in that seat, I think he’s absolutely right when we’ve sent our children to our public school system, even private schools, but this is really about public schools.

[00:03:27] When we send them, we have to entrust them to the professionals who are in place to do that. And so I saw his point at the same time. I know that when he was in governor, he’d be tilled a bill to expand the charter school law in the state. He also vetoed a education savings account. So I know he’s not a fan of both public and private school choice.

[00:03:49] And so when he makes those comments, it even makes Democrats who may not be fans of charters, who may not be fans of ESA saying, wait a minute. But you’re talking about the majority of our kids who are in [00:04:00] public schools. I should have something to say about their education through the lens of parental rights, so that all of a sudden galvanized a number of parents and not just Democrats, not just the , suburban white moms who some say that he speaking against it’s really a lot of parents.

[00:04:15] the number of phone calls that I’ve received in the last six months, even before that debate on parents who, because their kids were at home, whose kids were out of school. But the Catholic school, the charter school, we only have seven in the state. Really. We have, you’ll see that. It says we have eight, but there was actually a combination of the two.

[00:04:33] So it’s just a poor point to note. But anyway, parents were, are interested in options. But when this comment was made, a lot of folks who are Democrat, who are progressive, who are my friends were like, Something’s going on here. So the issue is moved to the top. So in reason magazine, they talk about this issue, but they also talk about the national school board.

[00:04:55] As you know, it asks the federal government to actually investigate and to intervene with [00:05:00] angry. Parents were showing up at board meetings. And for many people, they thought this was just a blanket. Yes. Across the board. Well, guess what the. Frustrated a number of board of director members across the country, including Virginia.

[00:05:13] Some actually decided to disaffiliate with the national organization. And there were a number of protests. There were some in loud county that had to do with something more personal. We can save that for a different conversation, but the article goes on and basically say that the polls are showing. That issue in education in general is closing the gap between Glen Younkin and Terry.

[00:05:35] And as a former governor, it shouldn’t be this close. Now I will say in the last gubernatorial race four years ago ed Gillespie, former leader of the RNC, he actually was within 17,700 votes of winning. So it was a close race, but for someone who was a former. Running against someone who hasn’t run before.

[00:05:57] This is going to be pretty close, naturally critical race [00:06:00] theory as a part of the debate. I’ve got my own questions and concerns about how the ride is handling and. There’s also the issue of homeschooling Virginia is a pretty strong homeschool state. What I was teaching at the college level, I had couple of students who were actually homeschooled private school market in Virginia, pretty strong as well, but you know what?

[00:06:18] We also have one of the best public school systems in the country. We have a pretty strong pipeline to our high school graduates who are going to four years. Schools and the Commonwealth, we’re also going to the military. Some are starting businesses and of course some who are leaving the state. So this is going to be a really interesting outcome.

[00:06:36] Now, if McCullough wins some will say this is a great, win for Biden because it’s going to show that he’s going to do pretty well next year in the midterm elections. If he loses some will say, ah, this is a Republican swell. This is a publican return. Well here’s how are we? The tea leaves to go to your original question no matter who went and it’s going to be three outcomes.

[00:06:58] Number one, families, [00:07:00] independent of party and independent of race are pretty clear that schools matter to their families. Number two teachers. Unfortunately, and I think often unfairly during the pandemic have been dumped upon is not doing their jobs. Parents and teachers have found unique ways of saying, listen, we’re not in.

[00:07:21] We’re partners, what can we do together to make things work? And so I think there’s going to be a pretty good PTA that organization with PTA movement moving out of this third, no matter what you think about critical race theory, we have to have conversations about race, even if it means being critical about cats.

[00:07:40] But if we’re being critical about our past, it’s also an opportunity for us to be. Glorious about our future. And so while this is focused on education, I think is a bigger issue. And I think no matter who wins, it’s not going to be a mandate, but it’s going to be an opportunity for us to exhale and show the country how we can lead a [00:08:00] divided gubernatorial election, come together as one Commonwealth and bring a common sense approach to teaching.

[00:08:07] Cara: Yeah. amen to that. Jordan. I have to say, to the point or the, light being shown on education in this race, choose things. So critical race theory is the hot button issue. It’s the painful issue. It’s the sexy issue, depending on how you look at it. Right. But I think that. Although, yes, that is certainly drawing some parents to school, board meetings, forcing some people probably on both sides to behave really uncivilly and in a way, not becoming too adults, in my opinion, who are supposed to be modeling behaviors for children.

[00:08:38] But yeah, of course we do. We’ve got a lot of things to address probably in our classrooms about race. And you can do that any number of ways I would imagine. But I also think, and this is probably part of what you were getting at. this, isn’t the only thing that’s bringing parents out. Can we not forget that?

[00:08:55] parents saw a lot during COVID, in addition to what was, or was [00:09:00] not being discussed about our history in their classrooms, but they saw a lot of stuff that they didn’t like. And I couldn’t agree with you more as a former teacher that you can’t teach and schools can’t be run if you have to cater to every single parents whim.

[00:09:14] On the other hand, though, the idea that parents are now. Probably more than ever exercising their voice in many cases with concern, right. Been locked up in our homes for 18 months or whatever the case is, and now you’re going back and, I’ve got some things to say. And it’s an unfortunate time because schools are strapped.

[00:09:32] Teachers are quitting, all of these different dynamics at play, but I hesitate to say, everything’s about this one particular issue when it comes to school, just like I hesitate to say, oh, Virginia is going to determine, you know, how the midterms go one way or another. That seems like a lot of pressure.

[00:09:50] And if the past 18 months have shown us anything, a lot can happen between now and then. Right. But it’s a really interesting one to watch. And I also just think for folks on both [00:10:00] sides of the aisle, Watch your language, watch your mouth. Think before you speak people, because it’s just like one little thing and then boil boy, you got yourself a bunch closer race than you thought you would.

[00:10:12] So I’ll be watching tonight. I’ll also be watching the Boston mural res and my city council race here because local politics matters too. And I think, it’s all really interesting stuff. My local school board race, I should say, and to all the school board members out there. Keep doing the work it’s good work.

[00:10:30] And now more than ever, it’s really, really hard work. All right, Gerard, there’s no way to do an easy pivot to my story of the week, but there is a parent connection here that I think is really worth highlighting. So I’m bringing to us, bringing to our listeners an article from the Washington post by John Marcus.

[00:10:47] And the title is, will that college degree pay off? And I have to tell you, I love. The opening to this article, because it talks about how, starting salaries for various professions. At for example, I think it’s like, [00:11:00] I’m sorry, I don’t have it in front of me. I’ve been, I read it earlier today, but that starting salary for folks who graduate, for example, with like an English lit degree or an anthropology degree is like around $18,000 a year, even though the cost of that degree might be $130,000 a year.

[00:11:15] Now, Gerard, as I know of. You before I have an undergraduate degree in English literature, which when I announced that that was going to be my major, my poor father, I think he had to take to his bed for about a week after I told him that he had dreams of medicine or law or finance, something like that, not to happen.

[00:11:32] And then when I came back a couple of years later and said, you know, dad. I need a graduate degree in anthropology. That sounds like a really good idea. It just looked at me and said, you are a lost cause. And, although I, pursued my passion and I followed my dreams and that doctorate and education would turn out to be the most lucrative career path I pursued.

[00:11:52] And I say that very tongue in cheek. It turns out according to the data and according to this report, my dear old dad, might’ve had reason to have a little bit of. [00:12:00] When I told him what I was going to be majoring in, in college and what I was going to pursue for graduate study. And that’s because, we do have data in this question of, if people are taking on so much college debt and what’s the return on investment.

[00:12:15] So I’m just going to point out a couple of statistics quoted in this article. The first one comes from a study that finds. 16% of the college programs that they studied. So that’s a portion of the programs that are available, but the data were available for these. So absolutely no financial return on inventor.

[00:12:33] Because it takes people so long to earn back what they took out, student loan debt and put into their college degree. So if you’re talking about $130,000 over time, like over the course of your education, and you start off with a starting salary of like 15 to $18,000, it takes you so long to earn it back that they say there’s actually no ROI.

[00:12:56] Another study found that , more than a quarter of programs [00:13:00] will actually leave. Less financially well off than they would have been had they pursued like a career. and just foregone college altogether. And, you know, this is just, it goes on to have this really interesting conversation about how institutions of higher education have avoided this kind of outcomes based accountability, like the plague, how they’ve sort of said, I think there’s a great quote in here from a scholar at AEI who says, they think that what they do is like unicorns and pixie dust, and it’s two magical.

[00:13:28] To wrap our arms around. And the fact of the matter is that the Obama administration had actually pushed institutions of higher education to show that people were actually getting some bang for their buck and they avoided doing so under Obama. And then Trump repealed the repeal of the law that was forcing them to do that.

[00:13:45] So I think this is really interesting stuff. And here’s the connection to parents, Gerard wait for it. I think that. Things we need to be thinking deeply about. And here I’m going to give a shout out to some of my wonderful colleagues at Accella Ned who have [00:14:00] produced a series of reports called pathways matter.

[00:14:02] And in one of them, spend a long time with parents. And one of the questions they ask is how much information do you use? As a student. And do you, as the parent of the student have about what different paths, whether you’re choosing college or whether you’re choosing some sort of career path certification technical education, how much information do you have?

[00:14:24] About how soon you can get a job? What kind of job you are likely to get? how much money you’re likely to make over the course of your career. And by and large, the answer that people give is. I have no information or I have such limited and confusing information that I don’t know what to do with it.

[00:14:40] And I think that this is an area, So many parents, my parents for sure are just convinced that college has to be the way and it might be the way, or it might be the way for reasons other than money. But so few families sit down and say, what is it that’s gonna be. Personally satisfying to me what [00:15:00] career path and what career path is going to be financially rewarding enough that I’m not going to be in debt with college loans until I’m, , past retirement age, or I’ll never be able to pay off that debt.

[00:15:10] And it’s just going to add to the federal deficit. So this to me is an article that spurred a lot of questions around what we’re doing. In high school and maybe even before to talk, not only to students, but to parents about different career options, as well as holding institutions of higher education accountable for showing us, is there proof in the.

[00:15:31] If I want to pursue a degree in anthropology, I should have known going in that the likelihood of me getting a job where I could actually support myself in a city like Boston is pretty darn low, so fascinating stuff. Highly recommend this read to anybody who’s interested. And yeah, that’s my story.

[00:15:47] The week.

[00:15:48] GR: My undergraduate degree is in philosophy, but I double majored in philosophy and anthropology. So you can, you can imagine the number of date that I lost when I left the school of [00:16:00] business, where there was potential for me and went to philosophy and anthropology, they’re like, oh yeah. So you want to pick locks and look at the stair to enable.

[00:16:09] Yep. I am with you in terms of talking to parents and students. One of our shows, I guess a couple of weeks ago we celebrated the was the economic week. And the important, difficult was the first time that we had an

[00:16:22] Cara: economic education. Yes. Financial literacy week. I

[00:16:25] GR: think it was, that was it. And it’s the first time that the national council, which supports economics and financial literacy said, listen, people need to understand this.

[00:16:36] Even for me using my own story, I decided to major in something I liked. I didn’t care if it was linked to money. Not partly. I also had worked, for several years before. BA degree from Howard university. So I knew what it took to get a job, but I wanted to major in something that made me think.

[00:16:53] Now it’s not a, I mean, it’s been a great return on investment for me, but yeah, I think we need to do that. The one [00:17:00] danger with it is that you start moving away from, in fact, when Marco Rubio was running for president he said, do we need more students majoring in enrollment philosophy versus stem.

[00:17:11] And I even worked for one time. who said in a meeting do we need anyone else majoring in philosophy and yet, I’m a secretary of education with a degree in philosophy, so, yeah. Yeah. So, I think we should talk about it, but I’m much more of a utilitarian. I want people to major in what they like, and I think the rest of it we’ll take.

[00:17:30] Cara: That’s true. And in all honesty, the value of a strong undergraduate liberal arts education in a discipline like philosophy or , English, language arts gives you a foundation. I think colleges would argue this and I would agree, Gives you a foundation to do many, many different things and to learn how to think and to write in all of the things that we know employers do value.

[00:17:52] But I think that the point that I want to drive home from this article is simply. People need to know their options and also [00:18:00] understand the various forms of return on investment. Because if you and I can say anthropology was good for the soul and it, it was, it, it is right. And it was so much now at the expense of my university of Chicago, which is not a cheap university.

[00:18:16] Master’s in social science. I don’t know. Well, I asked myself when I’m still paying those student loans 15 years from now, Gerard, who knows? maybe let’s revisit this conversation, then we’ll still be quite yet.

[00:18:27] GR: one last point, there’s a class dynamic and this as well, because even though we’ll tell people not to major in philosophy or anthropology, think how many people we talk out of going into a trade that somehow going to a trade or earning a certificate or licensure.

[00:18:42] Ooh, you should go to a four-year program. Electricians plumbers, master masons make a lot more than teachers they’ll spend as much time in school and get out quicker, but for some reason, and I think I know why it’s just a waste class and ethnicity [00:19:00] point with a long history in vocational race and politics.

[00:19:03] We talked to many students out of going to four year, but we also talked them out of.

[00:19:08] Going to

[00:19:09] trade schools, but we’ll see that for another call.

[00:19:11] Cara: and then what’s left, right? Yep. All right. Well, we’ve got a really interesting guest today, drug. We’re going to be speaking with pastor Robert Soto.

[00:19:19] He is a live in Apache religious leader, and he’s going to talk to us about. Many, many different things, including how he has gone to court to successfully uphold his native American cultural heritage and religious liberties, a topic we really enjoy hearing about here on the learning curve. So we’ll be back in just a moment.[00:20:00]

[00:20:14] Learning curve listeners. We’re very pleased to have with us, pastor Robert Soto. He’s an award-winning feather, dancer and lip and Apache religious leader who was threatened with criminal fines and imprisonment. Eagle feathers in his religious worship. He fought in court for over a decade to defend his rights, to practice his faith in Christ, as American Indian under the religious freedom restoration act.

[00:20:36] Soto presently is vice chairman of the lip and tribe of Texas. The tribe consisting of 4,500 members. He is the founder of son of tree native path, which has performed in danced in 20 countries and 46. So it was also the pastor of McClellan grace brethren church and the native American new life center in the Callan, Texas.

[00:20:57] My rock native fellowship in Brownsville, [00:21:00] Texas, and chief of chiefs Christian Church in San Antonio. In past years, Robert has had the privilege of working with the Seminoles of Florida and the pueblos and Navajos of New Mexico, along with 27 other tribal groups in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and south America.

[00:21:16] Pastor Soto holds a BA in biblical education from Florida Bible college, a master of divinity and a master of arts in Christian school administration from grace theological seminary in Winona lake, Indiana, and a doctor of arts and theology and biblical studies from south Texas school of theology. He and his wife over Soto have been married for 46 years.

[00:21:36] That’s amazing. And have three children, one adopted and eight grandchildren, pastor Robert soda. Welcome to the learning curve very happy to have you, sir, as the country is celebrating native American heritage month, could you begin by briefly telling our listeners about the lip and Apache tribe and your personal story as a religious.

[00:21:58] Pastor Soto: Well, Lipan Apache tribe [00:22:00] was it’s been around forever I guess like every year, the tribe. but we’re one of the few tribes in the United States that never signed a peace treaty with the United States. And so we kind of take pride on that because most of the tribes to be able to survive, have to submit to.

[00:22:14] What I call the tyranny of all these regulations and laws and restrictions that came along and the reservation life the Lamar Apache. So we learned to assimilate. We became some almost became ranchers and farmers, but we learned to assimilate into a non native community, but at the same time, never forgetting who we were and what we came from.

[00:22:32] So a lot of that. At the privilege, like my family to be brought up in observing these ceremonies and every year, culturally events, every year that happened that brought us close together as a community. But more important, but to light the fact of who we were and where we came from.

[00:22:50] And so, the look part of patchy drives to today consistent with the about 4,500 members. , about half of them are still here in the Homeland, south, Texas, but most of them are scattered [00:23:00] into areas like California, Washington, Oregon, and Michigan, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Florida, just around Oklahoma, New Mexico, just kind of scattered around.

[00:23:09] Which was our nature because we couldn’t spend all the time in one place because there were so many things that will come in against this. There was laws by the United States government that were created to basically annihilate the nation. People lost by, the country of Mexico which gave a bounty on the hair of our, people.

[00:23:29] I think at that time, 100 pencils for a man’s scalp and 75 for a woman and 25 for a child. And so we became just like any other animal hunted down for a little bit of money. And so, because of that, it forced us to basically go underground as a nation where we practice our language, we practice our religious.

[00:23:52] Ceremonies and prednisone culture. in hiding, heard stories from somewhere elders, how they used to go into the woods, into the desert, [00:24:00] away from people where they could practice some of these ceremonies, so that the, for fear that if they were caught, they would be sent to prison shipped to some reservation somewhere in United States.

[00:24:09] But at the most of fear, feared was, you know, shot, killed and scalped and become. economy of the state and the county or the country. we have a big, history as far as the Apache tribe is concerned. and because we didn’t sign that piece, really, back in the , 1870s, because we didn’t sign that peace treaty, I think was an 18, 18 78 around there.

[00:24:29] Today we basically have nothing. We had to fight all around.

[00:24:32] Cara: what about your own story becoming a religious leader? Can you tell us a little bit about your personal calling, your personal

[00:24:38] Pastor Soto: story? Well, first of all, story is basically we started because most of our, Apache tribes, half what we call holy people or people that were instead of part are designated To encourage us spiritually, to be there, to hold your hand. And when people died or just be there for word of encouragement and prayer, funerals, celebrations. And I just [00:25:00] happened to be brought up , in a family where our holy person was my grandmother. so I was, brought up seeing her.

[00:25:05] The way she, was and the way she acted and the way she responded to crisis and always being there for the people. so I, fell into that role that as I started to mature and grow up as a, that the more you are observed or the more she felt that maybe I was the person that was going to take over her role in our tribal community here in south Texas.

[00:25:26] And so little by little bit that. Being instilled into my heart my brain I had a calling in life and that actually even started way before when I was a little boy about a year and a half old I had this vision, they call them visions, maybe back then I called it a nightmare, cause it’s a nightmare.

[00:25:44] This. The whole world was being destroyed by fire. and I was on top of this big, giant cube blood structure. They had a walkway on the very top and I was looking to the exterior of this structure and that’s where I saw people suffering and agony. [00:26:00] And then I looked inside in the inside and there was a, there was people dancing and just having a fun time.

[00:26:06] then I heard a voice and said to go down to the. It’s just, you don’t belong to the outside. You belong to the insights that you’re special to me. , that vision came earlier. And now when I was a year and a half old and all my life, I’ve always felt that that was called to do something more in life than just function.

[00:26:21] then have a normal job. Somebody asked me a couple of days ago . What I did for a living, I says, well, I’ve been a pastor now for 46 years. That’s all I ever known. Plus before that. I was being mentored to be a spiritual leader in our community by my grandmother.

[00:26:35] So when I become a Christian and July the 26th of 1973. thought maybe my grandmother might be disappointed because I was the first Christian , in our tribal community down here. but she embraced the role because she saw that as a Christian, I took the role more serious, that I was the person holding people’s hands and I was the person doing the funerals.

[00:26:55] And I was the person, being there at their weddings and during their wedding from celebrations of blessings and all that [00:27:00] kind of stuff.

[00:27:01] Cara: So your grandmother surprised you a little bit.

[00:27:05] Just a few moments ago, you were explaining the very long history of your people, , facing extermination, quite frankly, and as other, all other native Americans and having to try and preserve your cultural heritage sort of underground. And I think that Many of our listeners would think of this as some sort of history long ago, which is in fact not the case because it was as recently as 2006, that an undercover federal agent rated your tribe’s traditional religious ceremony, seized sacred Eagle feathers, and threatened you with fines and imprisonment for using these feathers in your worship.

[00:27:41] So you with the support of the Becket fund, you’ve fought in federal court for over 10 years. To defend your rights under the religious freedom restoration act. tell us about that. I mean, not only the precipitating incident, the rate itself, but a decades long battle to preserve this part [00:28:00] of your faith, your

[00:28:01] Pastor Soto: heritage.

[00:28:02] I was just talking to somebody this morning. I’m helping now a friend back then. I didn’t even know he existed. From Mexico was sorta here illegally. And, but it’s a member of our tribe because we do have some members of our tribe, about 200, maybe 300 members of Mexico. A lot of people forget that there was no borders at one time and there was no Texas and there was all Mexico though.

[00:28:22] Just that land, there was a river. We call ourselves the aquatic techie. The, or the Colita, he means call me means water it’s I mean, big. And he means you long into, so we’re the people belonging to the big water, which is the root of the river that separates the tech system Mexico, the United States from Mexico.

[00:28:40] and so a lot of people don’t realize system, the whole historical significance of. Things that are going on. And, again, going back to that peace treaty that we didn’t sign back in the 18th, 1878, I believe around that time we have more rights today because at the end of the day, and we know this all our lives at the end of the day, it’s the government who designed who is, and [00:29:00] who’s not a native at the end of the day, it’s going to decide who can, who cannot worship.

[00:29:05] And if you don’t belong to a tribe acknowledged for the federal government, then in reality, you have very few religious rights when it comes down to it. our indigenous culture and the practices that we like to practice. So a lot of our religious services or religious ceremonies, like I touched that earlier, went underground.

[00:29:24] Because there was a bounty , in our hair and there were two, our lives were in danger, just repeating the fact that we were looking on Apaches and that even our language started to die out recently, we started to restore it again but just the whole cultural experience of the native was, but we still kept this almost kept it really strong.

[00:29:42] so when this government, whether you’re into the government sent agents, and we say agents, we only saw one, but there was two other ones that were acting as tourists and had cameras, and they were going around asking people what we are. Oh, that’s a pretty looking head piece.

[00:29:56] What’s in it. That what kind of feathers are those, the right questions. And there were [00:30:00] documented. Well, this interview is and taking pictures of all this, and we’re just taking pictures with people we thought were touristy, , they weren’t wearing any uniforms as badges and stuff like that.

[00:30:09] but we always known that that was a possibility. One of the reasons I think that I reacted so well to them coming to our gathering is that I’d been practicing since I was a kid. And some of the kid I was practicing, what would I do? And what would I say if I ever was confronted by the agents of the United States government and were in question, my, spiritual.

[00:30:29] The other thing people don’t understand. And then they’re just very difficult living in a nation where everything is separated between church and state our native community in a, the old traditional way. There is no separation of church and state because that, which is secular meets in the middle of where the sacred, but secretary becomes taken was sacred, becomes.

[00:30:50] because it all brings us up community together. that’s one thing that , they don’t understand about the. the Paolo if you’re a traditional person and that we are always, we’ve been [00:31:00] taught that way since I was a little boy that the towel is a sacred ceremony, because there’s a circle there and there.

[00:31:08] And because of the there’s prayers that go out there, there’s ceremonies, you go out there blessings to go out there and, the United States government can understand that because, when you guys go to a dance, you don’t go there to worship God, you buy their dance, and they see the same thing with this in our native communities.

[00:31:22] Well, they’re getting together at a Palmer to dance. How can that be sacred? Well, it’s sacred because of everything that goes on within that circle. , there’s things you do and things you’re with, you know, the native community were told when an elder rebuke says, he goes, man, I got a good cussing out by my elder design because I blew it in the circle.

[00:31:39] , it’s like, be acting bad in church. You you’ll, you’ll hear it. When you get home, you’re going to , get it from your parents because you weren’t sitting still, , and that’s the way it sort of, we would teach our kids that way. We teach our kids that that circle is sacred and the government understand.

[00:31:54] for us, it was just an, I could go on forever, you know, it was this, but it was, I was just totally shocked when the agent [00:32:00] finally confronted actually started with my brother-in-law outside the circle because they couldn’t come into the circle. They could have come to the building with a circle unless had just caused it.

[00:32:08] A crime had been coming. of course, they went after my brother-in-law, who was wearing 46 on my Eagle feathers. I loaned them to him they went after him. And when I confronted the agent then he went after me and in many ways, I, when I guess his desires, he could say, I’m the agent of the federal government.

[00:32:26] fishing game. And I went to Eagle feathers and I need to improve didn’t show me as bad. So I, I didn’t know you telling me the truth. And I had to ask him three times for his bad that’s when he probably asked for his badge, he said, I’ll give you your Eagle feathers. I go to the whole, you can’t have my Eagle feathers.

[00:32:41] He says, why not? He goes well, but it’s a merkin. And he goes, I have this right to this others. I did my best to keep him from going into the circle. this is where I was totally surprised or. They, he said the reason he could go into our circles because , we violated two laws, two federal laws, not where those books, those laws are in the books or not.

[00:32:59] We don’t know, [00:33:00] but they, I assume they are because they also came out the early part of my court case, the federal court case, the first law we had violated was we advertised our gathering in the newspaper. And very soon discovered that, that made it not just. People don’t belong to a tribe, not acknowledged by the federal government, any, tribal community advertises their gatherings, where the, you know, especially the religious gathering.

[00:33:22] They said, once you advertise it ceases to be sacred, it becomes a public event given the government every right to come and do whatever they want to do. that was one of the laws we violated. The second law we violated was the exchange of. They asked me questions in court, but even as the agent was trying to get in, he says, he asks me questions.

[00:33:40] Like, are you holding a raffle, our vendors selling their goods around the circle. I go, so are you having a tape wall? Are you having a 50 50? And then finally at the end, he goes at any time, did you honor a veteran by putting a dollar in his feed in the circle. And when I said yes, at the moment, a dollar is the [00:34:00] circle, it seems to be safe.

[00:34:02] but that’s what we honor, people were honored. People were bring them to the middle of the circle. It’s a religious ceremony and we honor them by giving them gifts. Then one way to give them gifts. Everybody puts money on a seat, you know, that’s the way we honor them, and so there was just ludicrous charges because.

[00:34:15] been a pastor for somebody along the, you know, what I do for a living as well. All I’ve ever done is a pastor. Since, my messages, I was 21, that’s all I’ve ever done. the pastors, I mean, patching for 46 years then as all I know what to do. And, we’ve advertised before the newspaper or Christmas gatherings and our Easter Sunday gatherings and this, Does that violate our sacredness because we advertise and we have the offering every Sunday, does that violate our sacredness because monies falls into the sacred ceremony, gatherings or church gathering.

[00:34:46] And so I saw that there was laws that were okay for the non-Indian community, but not okay for the native kids. Sure.

[00:34:53] GR: This is the kind of information that we want to share with our listeners. I’m learning a lot. I knew something about your [00:35:00] story from the past, but to actually have you here is important.

[00:35:03] Let me do one pivot before I pivot back to this story. most of us are unaware that when you think of states, I connect. Or Alaska, Oregon, Alabama, over half the us states have native American names. And you look at cities like Chicago or bill walkie, where I used to live Cheyenne, Seattle, Miami, or among the cities with Indian identities.

[00:35:24] we have numerous rivers,

[00:35:25] Pastor Soto: Missouri

[00:35:26] GR: river, Mississippi river, Arkansas, Ohio. And it goes on in your view, how well does American education teach our children about many elements of native American history and culture? That are so deeply embedded in our culture that frankly we take for granted, what can we do to better highlight it?

[00:35:44] Pastor Soto: I think education is so. important. The problem we have in our native community. And unfortunately you’re, if you’ve heard the saying that the squeaky wheel gets the oil, and it seems like every ethnic group, the African-Americans, the Mexican Americans, the Asian Americans, and [00:36:00] all these people have the squeaky wheel and they scream the loudest.

[00:36:03] told people we’re the only nation where we get persecuted. We treated in quietness and humility and we take it to. and decide what to do. and so I don’t understand what it is to be an American Indian in the 21st century, and I think education really help.

[00:36:22] and that’s something that we’ve been trying to do here in Texas. It’s better educated that even though Texas doesn’t recognize any American Indian tribe except there’s three, but those are recognized by the federal government a little more . Who our daughter reservation from other reservations that were outside founders of Texas, but they’re not texted.

[00:36:41] They weren’t brought up in Texas. they didn’t roll on this land. They just came later and called them winter Texans. So people that came in later but the tribes that are from the state itself, the looking at Apache is the Comanche. The , the

[00:36:57] And the list go on and on. He goes, [00:37:00] those nations are still here today in this area. But nobody’s aware of us. we do presentations in schools from time to time , and we were doing this presentation with fifth graders. So it was six, fifth grader classes there.

[00:37:12] They’re about 150 kids. Were there. and the teacher said, well, you know, this is a new for the kids cause they don’t have a native except for your two nephews and two nephews that were twins. We’re there. Cause he gets to be two nephews to go. We have no Indians in our school. And before I started the presentation, I asked the kids.

[00:37:28] I said, how many of you here know you come from native tribe and had been educated by your families, that you are somebody other than. and it says, if you can you raise your hand and they were surprised at one third, one third of the fifth grade population could claim routes to a specific tribe.

[00:37:52] And not only that, but several teachers raised their hands and parent helpers raised their hand. and so people don’t know that we’re around them. [00:38:00] So try to educate people. For example, there’s a little community just down the road, about an hour and it’s called far 40 years and people think that’s a Spanish name.

[00:38:09] So I will tell people, do you know what, what food is means? It says, well, it’s just some, some Mexican names has no on a patchy word. That means hearts, the light or a place, a rep of rest. And I gave him the history of how that got the name. And this is this the street here. Everybody’s always wondering, I always wondered as a wassup, what was on there once I had to be a native name?

[00:38:33] Well, what else could it be? You know, and it’s a walk outside of the sandwich between Sue road and Minnesota and those sort of native territory. So I, one time I was up and I grew a lot to, Chipotle country up in the cam, Michigan, and, and I was talking to them in with the expert.

[00:38:48] And I answered those out of curiosity. He goes, do you guys have a word by the name of a WASA? He says, well, actually we have two words that are very similar to each other. We to have a walk and we have a Watso and she said WASO means a great leader or [00:39:00] chief. I said, but a Watson means a far away place.

[00:39:04] And so what I concluded once that there was some, maybe some migrant workers that went up to Chippewa Atlanta and Michigan and Minnesota, he married a person, maybe a, man married a person and brought his Chipo wife to south Texas and, started a little clumps that they’re a little ranch and they named that road in front of a WASA, but she wasn’t on faraway place, you know?

[00:39:24] these are the stories that I take neat, to be. Brought up bring to awareness that this land was the rich places are made in communities, whatever tribes they might be. So what we’re doing are we in our tribe? We’re trying our hardest to educate people.

[00:39:38] lot of times our fights are not in the courts that ever get to go to court, but we fight them on this, you know, outside of courts we win. By educating people who we are, we take a stand take a stand and show them that we’re still alive during war.

[00:39:50] GR: When we often talk about native American history, we’ll talk about the trail of tears.

[00:39:55] We’ll talk about what happened to the Seminoles and the tragedies. And you’ve shared some of [00:40:00] those. What are some triumphant stories of your. That we may not know about, but you’d like to share with us in order for us to share with our family, friends and

[00:40:10] Pastor Soto: others. I think it’s important to understand that wasn’t just the turkeys would have to travel in tears.

[00:40:16] Just about every tribe in the United States had a trail of tea, especially the tribes in the central party, United States and the Western part United States as they’re being removed. And, and a lot of them were sent to the, Indian language and call Oklahoma today. But a lot of them being taken from their homelands and shipped into reservations, especially the Apache people and the people in the Southwest where we’re the last to be conquered.

[00:40:37] And because of that, a lot of those stories are still fresh in our minds because there were, the role was beautiful. Among our tribal community but like anything else in life, we have to make a choice we get to choose to be defeated, or we choose to have the victory.

[00:40:52] And the Apache tradition, we just say that the white man’s would say, well, how can you find somebody who also is always fighting behind the cactus? [00:41:00] They were always hiding. There was no trees that had to be cactus. I tell our, people and our children and our grandchildren and our youth, we didn’t get this farm by hiding behind campus.

[00:41:09] we’ve had to take a stand and some of us have to have to die for the, for the kids of freedom. , and a lot of people don’t realize it’s just like, for example, a lot of people don’t realize that. That among the medical community. We have, heroes in our native community.

[00:41:21] we have one member of our tribe who was in charge of all the troops in the Southwest Pacific. if we went to war, this man, was it he’s a, he was one of our people and, and, and the, you know, and he was in charge of the literally thousands and thousands and thousands of men and women were here protecting our freedom.

[00:41:37] And, and here he was being, he was being a, what do you call it? Um, It would be being led by one of our members. We had another of our tribal members who every time there’s a war, he would disappear because he was an expert in hand-to-hand. And he was always being sent to the middle east to train our troops, to protect themselves in case their Berber attack, and they know how to defend themselves defense on [00:42:00] from, from knives and things like that.

[00:42:02] But we have a lot of, a lot of personal small victories, you know, because we don’t let persecution knock us down and I try to encourage everybody to stand up and keep fighting, stand up and keep fighting. I said, we just never give up, never give up. We just stand up and keep fighting.

[00:42:14] and we have a lot of personal victories. When I told people that I was going to Sue the United States government for taking our feathers, they all laughed at me. All the native, a lot of native people laughed at me and even family members laughed at me because nobody ever said broke one against the department against United governor department here.

[00:42:29] It was,, we’ve had small victories, but never something like this, ?, so people would kind of laugh at me. It’s all, you know, When you win and you’re like, yeah. , , 10 and a half years later when I finally opened the case, everybody’s patting on the back and said, we were right behind you.

[00:42:42] We’re right there with you. But that was a big,

[00:42:48] I mean, I wish it had been a big deal for all our people. Unfortunately, I could only get about 200. 30 of our people in that list of practice lists, because the word came out at the end. And I wish the whole, tri would have been part of [00:43:00] this victory. We’re fighting on that now, but it’s just that, not just that, but I mean that my case has been used in some places like the, pipelines that went to North Korea.

[00:43:10] They were using that over the issue of destruction of sacred sites. there’s another flight in San Carlos, Apache people. they’re taking their sacred grounds. I mean, they’re, they’re sacred ceremonial grounds for hundreds of years, and they’ve got to make it into a big, giant compromise there that at the end, we’ll have a whole three miles in diameter and 95 feet.

[00:43:32] And, and the host EV the soul server program, , we’ll be um, would be gone. And I thank God that right now, I think is involved with that. And without one and other people that use this case. So even though with like a small little thing, and I really thought nothing about it, and, but as well to see how a lot of people are using that for their own personal defenses, the American Indians, and, but it’s also tribes for some of their sacred.

[00:43:57] And you know, and I’m sure [00:44:00] that, you know, we could keep talking about all the little victories, but that’s something, that’s our people. We just keep working. We get finding, we keep working, we keep fighting. We never stopped onto our ticket last breath. Where’s my.

[00:44:10] Cara: No, I was going to say, it’s just, it sounds like you’ve had an impact in that case.

[00:44:14] It said it had an impact that you never could have imagined when you were only one and a half years old and had that, dream had that vision. pastor Soto, I’d like to just thank you so much because unfortunately I think we could talk to you for hours, but unfortunately I think our time together has, come to an end.

[00:44:30] It’s just, yours is an. It’s a fascinating story, but I think more than that, it’s a really important story. So thank you so much for lending your voice to the learning curve today. And I know that our listeners will be very appreciative.

[00:44:43] GR: . . So my tweet of the week is from education next. November 1st dismantling Denver, the city was a national model for education reform. Then union back. Took over the [00:45:00] school board. I had a chance to study a lot about Denver schools when I was in grad school. And I will watch this with great interest.

[00:45:07] We’re talking a lot about school boards, primarily about critical race theory about bathrooms, about COVID, but there’s a whole lot school boards do. And when a place like. Is at least under the microscope of not being what it used to be. It’s something we should take a look into and if it could happen in Denver, it can happen in your school system as well.

[00:45:29] And it’s not about whether it’s union or not. It’s about who you put in office and for what reasons?

[00:45:35] Cara: Absolutely. Gerard you’re never wrong. My friend. Okay. Rarely. Well,

[00:45:39] GR: my wife she’ll.

[00:45:43] Cara: All right. , I’ve got a friend of yours coming up next week. Gerard, next week, we are going to be speaking with Jennifer Laszlo Mizrahi.

[00:45:49] She is the president of respectability, a nonprofit organization, advancing opportunities so that people with disabilities can fully participate in all aspects of community. I’m [00:46:00] definitely looking forward to that conversation, Gerard until then take care of yourself. And I’m sure we’ll have lots to discuss next week

Recent Episodes:

Edward Achorn on Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, & Slavery

PRI’s Lance Izumi on The Great Classroom Collapse

AFC’s Denisha Allen on School Choice & Black Minds Matter

UK’s Prof. Richard Holmes on Coleridge, the Ancient Mariner, & Poetry

NYT’s Anupreeta Das on Bill Gates, Microsoft, & Tech Billionaires

National Alliance’s Starlee Coleman on Public Charter Schools

Houston Supt. Mike Miles & Urban School Reform